Co-living could spur office-to-residential conversions, returning Seattle to its affordable SRO roots.

Using a “flexible co-living” model in office to residential conversion projects could significantly cut costs and open up new opportunities for creating affordable housing in downtown business districts, according to a study recently released by The Pew Charitable Trust and Gensler, a global architecture, planning, and design firm.

The study looked at office to residential conversion scenarios in Seattle, Denver, and Minneapolis, cities selected for their high office vacancy rates, large numbers of cost burdened renters, and regulatory environments favorable to implementing a co-living housing model. Overall, the study found that while the co-living model significantly decreased conversion costs, some level of financial subsidy would be necessary to make the office to residential conversions financially feasible, albeit less than what is currently being spent to create conventional affordable housing units.

The City of Seattle expressed enthusiasm in response to the Pew and Gensler study’s findings.

“The City continues to be very supportive of efforts to convert underused commercial space to housing, including co-living housing. Increasing housing supply downtown is an important strategy to advance goals for both downtown activation and housing affordability,” wrote Seferiana Day, communications manager and council liaison, in an email to The Urbanist. “We recognize that a limited subset of buildings will be viable for conversion, but even a small number of conversions can have a strong positive impact.”

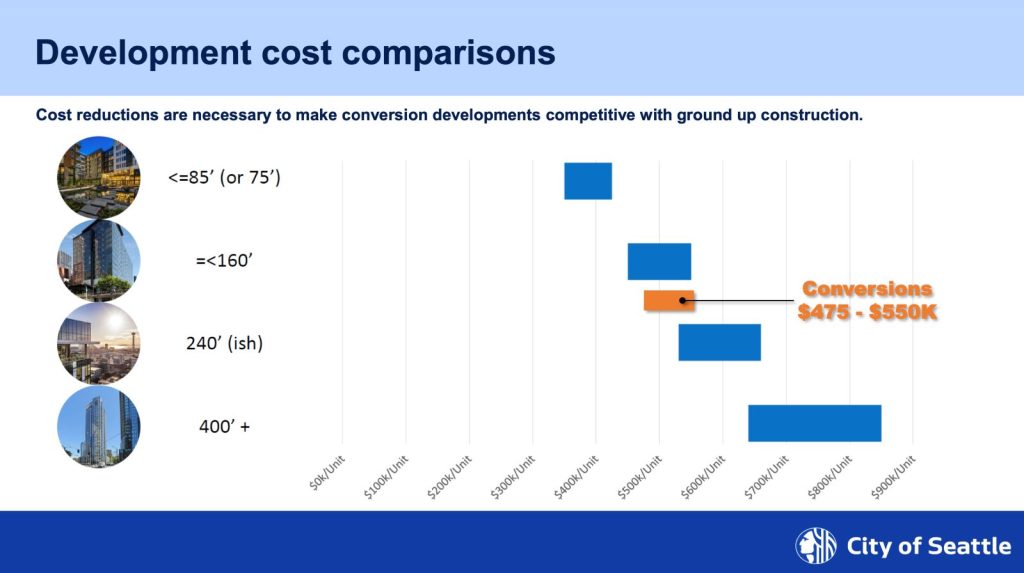

In July 2024, the Seattle City Council passed a slew of legislation aimed at supporting the conversion of existing commercial buildings to residential use. Analysis from the City’s Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) estimates that 1,000 to 2,000 homes could be created in seven years, at a cost typically exceeding $400,000 per apartment.

Critics have cast doubt on whether such office conversions would actually materialize given the high cost and challenges of overhauling office buildings to meet residential needs. A construction cost of $400,000 or more per residence borders on the cost of new-build apartments, which likely would have less awkward layouts compared to converted offices.

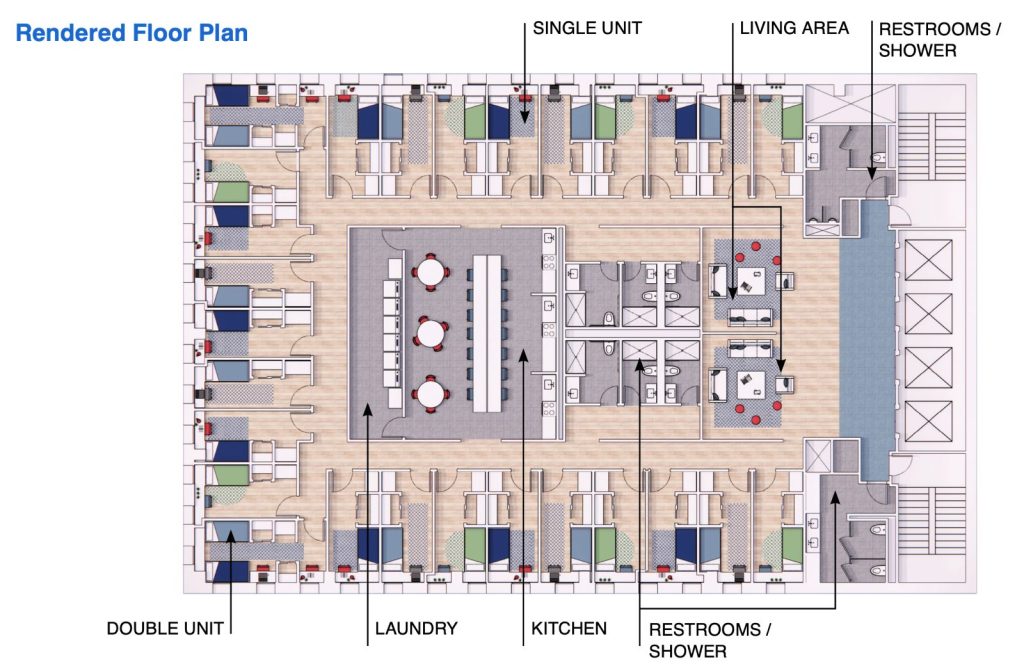

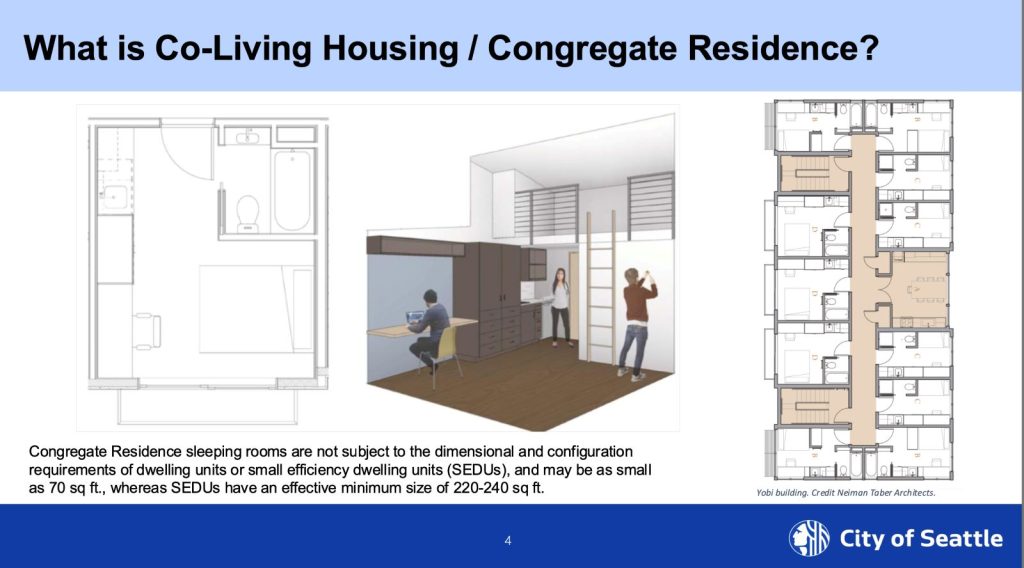

Using a co-living model, however, could reduce conversion costs to about $190,000 per sleeping unit, according to the Pew and Gensler report. The flexible co-living model, which features shared kitchen, bathroom, and gathering spaces, reduces conversion costs by maintaining centralized plumbing systems prevalent in office buildings and by creating space for about three times as many dwelling units as a traditional residential apartment building.

The study focused on the conversion of mid-density high rise buildings of about 20 floors that were constructed in the 1970s and 1980s. These buildings were selected because they constitute about 40% of the selected office building inventory and have similar floorplates, developer lingo for the shape of each floor of a building, particularly the leasable square footage.

For the study’s purposes, a typical single occupant sleeping room was defined as 120 square feet, and included a twin XL bed, desk and chair, and nightstand along with a microwave and half-sized refrigerator to store personal food and beverage items. Each floor would have about 29 residents and provide those residents with access to a kitchen, dining area, living room, and laundry area. For bathrooms, there would be six single occupant restrooms with showers and three additional toilet rooms per floor.

In terms of rental cost, the report set rents of $1,000 per month for singles (the majority of sleeping units) and $700 per person per month for doubles. These rental costs would be affordable for single person households earning 30% to 50% of Seattle’s area median income (AMI).

Construction costs were assessed at about $350 per gross square foot (GSF), which includes about $70 per GSF for mandatory seismic retrofits. The study’s development pro forma estimated building acquisition cost at about $16 million or $75 per GSF.

The study looked at alternative financial scenarios, such as scenarios in which there would be no building acquisition costs, as well as scenarios in which local grants, below market financing, and/or tax credits would be provided. While the study determined that “the project may require an additional level of subsidy to attract necessary capital,” it expressed optimism about the co-living conversion project’s potential to attract some level of subsidy because of the relative affordability of the cost per sleeping unit.

One potential subsidy may be the sales tax incentives for converting underused commercial buildings to affordable housing passed by the Washington State Legislature earlier this year. The bill allows for developers of commercial to residential conversion projects to apply for sales tax exemptions if they commit to making a portion of the future homes affordable to people with low or moderate incomes. The Seattle City Council is expected to vote to adopt the sales tax incentive in the coming months, building on a regulatory incentive package passed in May — also prodded by a state mandate.

According to Day, the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) has reviewed the report and “believes that the regulatory supports and incentives the City has passed and continues to work on can support the type of co-living housing studied by Pew and Gensler.”

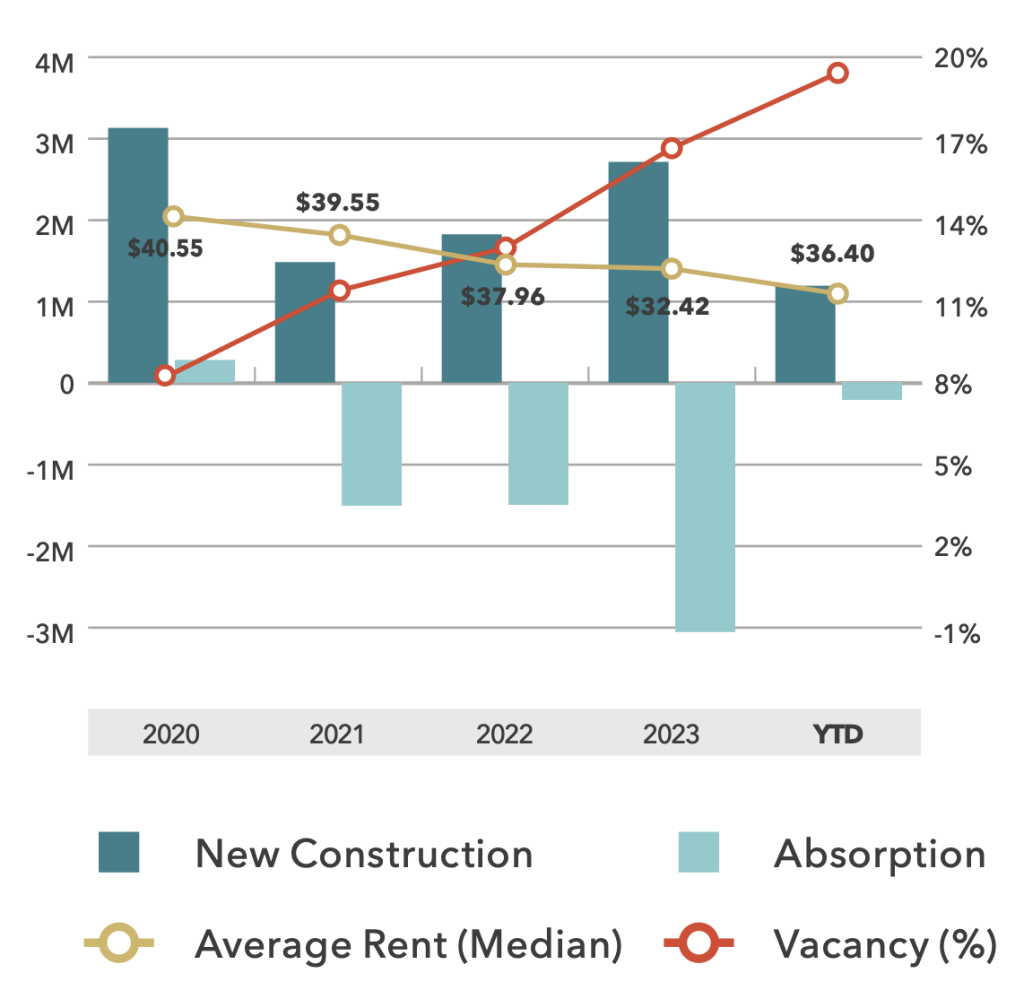

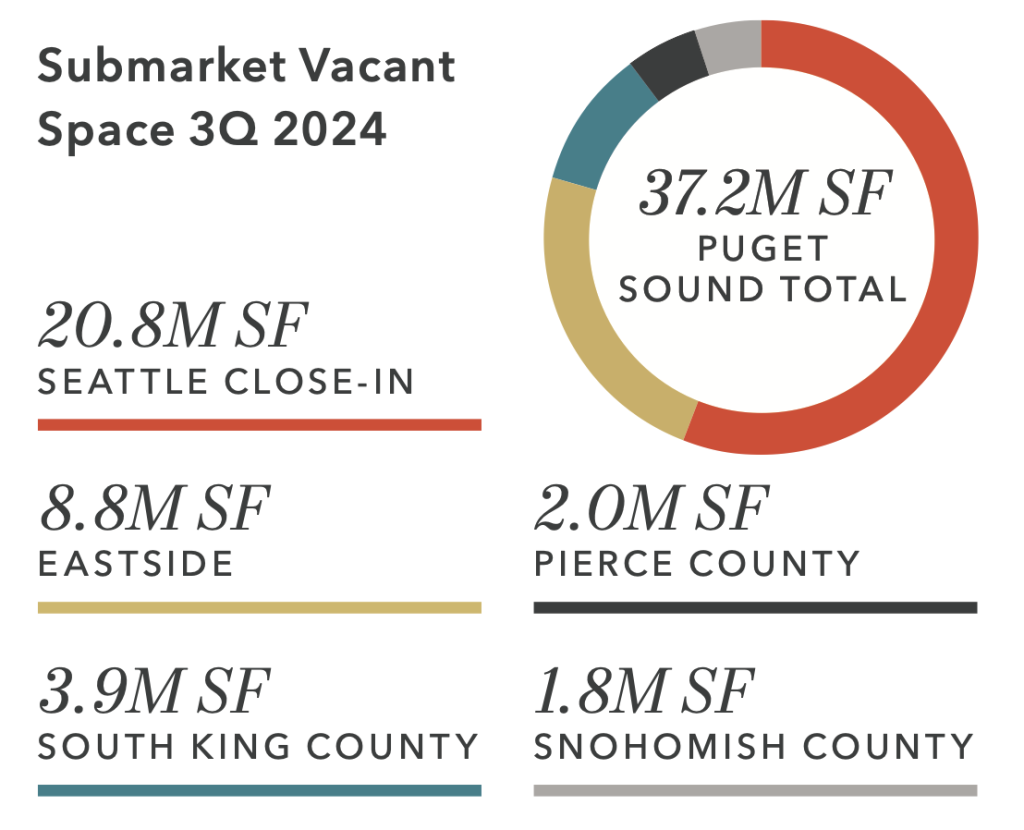

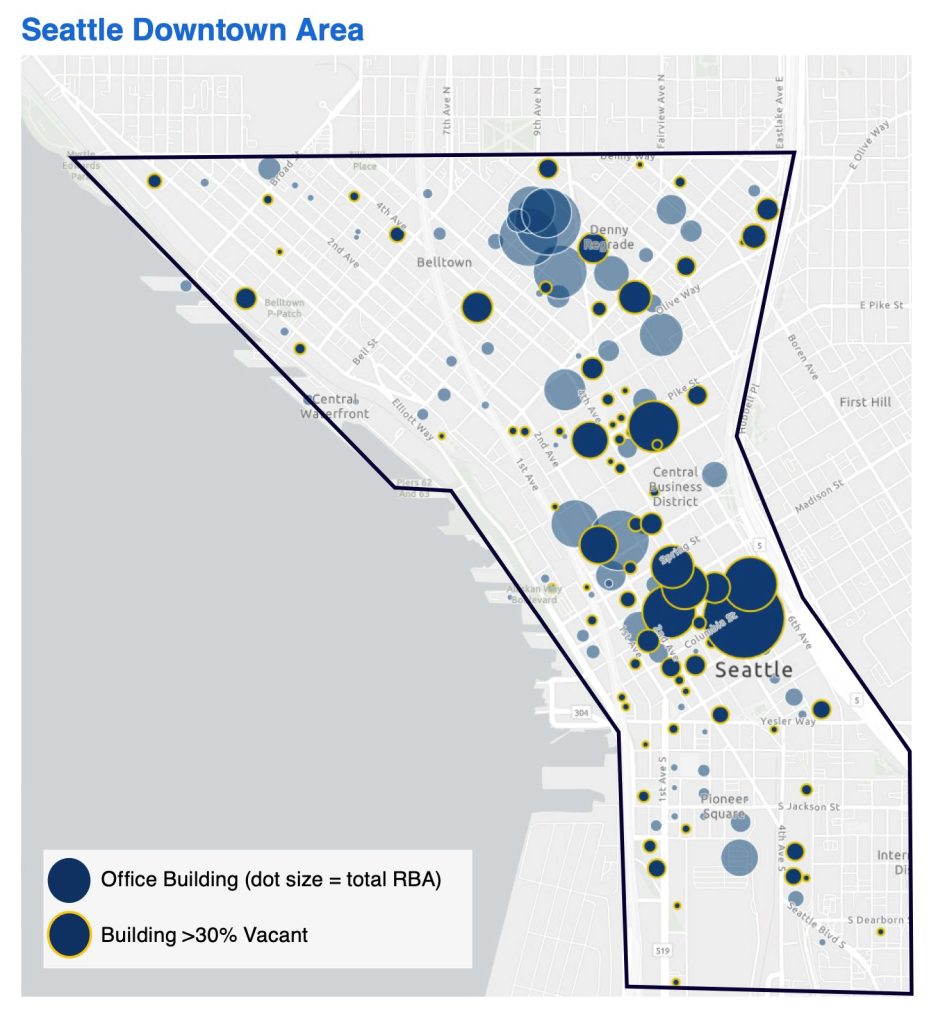

Post-pandemic, Seattle office vacancy rates continue to climb

Research by commercial real estate firm Kidder Mathews found that office vacancy continued to rise in the third quarter of 2024, reaching a vacancy rate of 27.6% in Seattle’s Central Business District. In the city of Seattle as a whole, office vacancy rates were reported at 19.42%, the highest percentage in the region. This percentage translates into roughly 20.8 million square feet of vacant office space. When analyzing the Puget Sound region as a whole, Kidder Mathews estimates that about 37.2 million square feet remains vacant.

It is important to note that the Kidder Mathews estimates of vacant office space do not include vacant or underutilized office space currently held under lease, and it is unknown how many companies are leaving office space mostly, or entirely, unoccupied as they wait for their leases to expire, a figure that could be substantial. It is possible, however, to measure how office vacancy rates have continued to climb even as office rental prices have decreased, a trend indicating a distressed commercial real estate market.

While Kidder Mathews projects that cuts to interest rates in September by the Federal Reserve and upcoming changes in workplace policy, such as Amazon’s pledge to require employees spend five days per week in the office beginning in January 2025, could help Seattle’s commercial real estate market to rebound, the shift to increased remote work options for office workers appears to continue to present steep challenges to downtown business districts in cities like Seattle, whose economies have historically relied on a daily influx of office workers to thrive.

The City of Seattle’s effort to increase the number of downtown resident in order to make its downtown more resilient is in line with research findings by organizations such as the Downtown Recovery Effort, a program run by the University of Toronto’s School of Cities, whose research has linked post-pandemic recovery with the presence of sectors like housing, education, healthcare, entertainment, and manufacturing in downtown districts. Seattle sits near the bottom of its Downtown Recovery Rankings, coming in at 63 out of the 66 North American cities studied using 2023 data.

Researchers attributed the ranking to Downtown Seattle’s high number of IT and management jobs, many of which have not returned downtown post-pandemic.

Potential high demand in Seattle for affordable co-living housing options

While the co-living model might not be a good fit for all types of households, according to the Pew and Gensler study, 58% (119,000) of Seattle renters live in single occupant households and approximately 16% (19,000) of Seattle’s single occupant renter households earn between $30,000 and $50,000 annually, creating a large potential customer base for this model of housing.

“Adding large amounts of this low-cost, downtown housing would provide a much-needed option for students, service-industry workers, young professionals, veterans, new arrivals in a city, and retirees. It would also reduce homelessness,” the study argues. “And because of these units’ small size, the current low prices for office buildings, and the efficient layout, this housing could be created near jobs and transit at a fraction of the cost of traditional houses or apartments.”

Seattle has had a long, and at times contentious history, with micro-apartments and co-living housing. Once Seattle’s downtown was the site of thousands of units of affordable housing, mostly in the form of single room occupancy (SRO) hotel and residential buildings. In 1970, after a fire at the Ozark Hotel in downtown Seattle led to the deaths of 21 people, the City began to pass legislation that led to the destruction of thousands of units of affordable housing in downtown and nearby neighborhoods.

From 1970 to ’71, 40 hotels and other residential buildings, mostly in the Skid Road area, were closed and another 21 were demolished, eliminating a total of 3,264 units of low-income housing. In a 1983 inventory completed as part of the environmental impact statement prepared for the city’s downtown revitalization plan, it was estimated that between 1960 and 1980, 15,622 housing units were lost in an area comprising downtown, South Lake Union and First Hill. Of the 13,093 units that remained in the downtown area in 1982, nearly 4,000 sat vacant and only 7,311 were affordable for low-income residents.

– Sinan Demeriel, “Roots of a crisis,” Real Change, 2016

The Pew and Gensler report noted this history, referencing how across the United States, cities once were “characterized by an abundance of lower cost housing typologies, particularly single room occupancy (SRO) dwellings.” The report estimates that as a result of changes in zoning, building codes, financial incentives that prioritized other forms of housing, SROs were effectively eliminated in American cities, with an approximate 1 million SRO units lost to conversions and demolitions between 1970s and 1990s alone.

Shared housing began to make a comeback in Seattle between 2009 and 2015 with the popularity of micro-apartments, small individual apartment units ranging from 90-200 square feet that featured private bathrooms and kitchenettes, along with shared fully functioning kitchens and laundry facilities on site. These developments were so popular that in 2013 micro-apartments constituted about a quarter of new housing created in Seattle, which translated to 1,800 new homes, many of them under the “Apodment” brand.

But this particular micro-housing boom was not to last. Concerns over the impact of micro-apartments on neighborhoods, in particular on parking, led to restrictions on minimum unit size, the addition of design review requirements, and a prohibition on the creation of congregate housing like Apodments in areas zoned for low-rise apartment building and neighborhood commercial centers. These changes mostly brought the congregate housing boom to an abrupt halt, but they did not end consumer demand. Developers turned to the creation of small efficiency dwelling units (SEDUs), small studio apartments of at least 220 square feet in size, but these homes often cost significantly more to build and correspondingly higher rents.

Recently the Washington State Legislature and City of Seattle have passed legislation in favor of congregate housing. In compliance with state law, congregate housing can be permitted in all multi-family zones in the city, including low-rise zones.

The approved legislation allows for sleeping rooms as small as 70 feet in congregate residences, and exempts them from the design requirements of SEDUs. The definition of congregate residence was amended to describe a residence in which, “sleeping rooms are independently rented and lockable and provide living and sleeping space, and residents share kitchen facilities and other common elements with residents in a building.”

The legislation also deleted parking requirements within a half-mile of a major transit stop and reduced parking requirements to one spot per four sleeping rooms elsewhere.

Are Seattleites ready for this style of co-living?

Last July, Charles Mudede, senior staff writer at The Stranger, penned an essay critiquing steps the Seattle City Council had taken to facilitate the conversion of office to residential space in downtown Seattle as a “distraction” that would “throw money at developers to make even more unaffordable apartments.”

As a solution, Mudede suggested a pivot to congregate residences, much like the flexible co-living design plans studied by Pew and Gensler. But Mudede recognized that part of moving to this style of housing will require rethinking some of our middle class norms around housing.

It should be pointed out that not having access to a private bathroom or sink may be a dealbreaker for some future residents. At the same time, with a potential customer base estimated around 19,000 renters, it seems likely that Pew and Gensler’s co-living model would be an attractive option for some renters, especially those who prioritize affordability and access to employment, transit, and services.

Many factors appear to be shifting the balance in favor of creating more small, affordable homes in Seattle, and these same factors, along with the need to address the high levels of vacancy in downtown office buildings, could provide momentum needed to make the designs studied by Pew and Gensler a reality. If such a trend materializes, it would help return Seattle to single-room occupancy roots when the city was more affordable.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.