With rising costs and waning support, Seattle’s Center City Streetcar project is clearly in a fragile place. This budget season, the Seattle City Council took to the issue like a bull in a China shop. Councilmember Rob Saka proposed decommissioning the South Lake Union Streetcar, and Councilmember Bob Kettle pushed to formally abandon the Center City extension from official capital improvement plans.

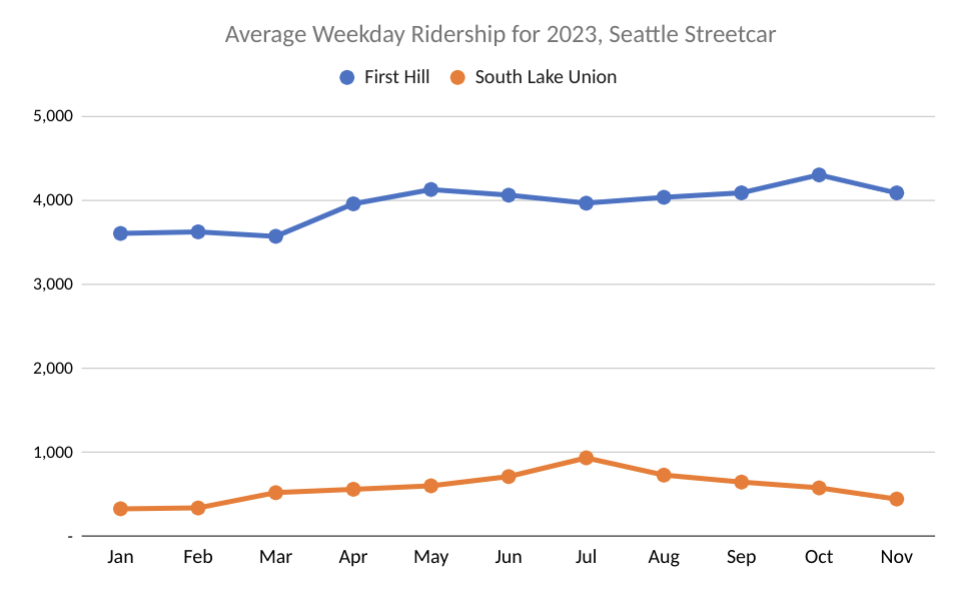

While failing to get their official plan to decommission the South Lake Union (SLU) Streetcar, the anti-streetcar contingent did succeed in a symbolic victory by getting the Council to take a step back when it comes to the Center City line, approving Kettle’s amendment. But the reprieve for the SLU line appears a hollow one since it ridership is anemic at around 500 average daily riders in 2024, and the plan was always to extend the 1.3-mile line to increase its utility.

Without the Center City project to close a key 1.2-mile gap in Seattle’s streetcar network, the SLU line will continue to struggle to attract riders. It will have to fight to safeguard its operating funds from councilmembers-turned-buzzards trying to pick its bones every budget season. Rather than being cured of its long-term ailments, the South Lake Union Streetcar will remain on hospice care, but clearly on death’s door awaiting the next crisis.

Completing the Center City Streetcar extension is the logical thing to do, especially for those wanting the SLU line to survive. While several councilmembers have wrung their hands about the cost of the project, it remains a prudent investment, practically a rounding error in the budget of a Sound Transit light rail line.

A double standard: West Seattle Link vs Center City tram

Without batting an eye, Seattle leaders opted to add about $700 million in estimated costs to the West Seattle Link light rail project by adding tunneling in Alaska Junction — apparently because they don’t like the way elevated rail would look. Overall the West Seattle Link’s expected budget has skyrocketed from $4 billion a few years ago to about $7 billion, due to inflation and routing decisions.

Such cavalier cost-increasing actions makes whining over a few hundred million dollars in costs for the Center City Streetcar look silly in comparison, and clearly a double standard. Inflation is hitting nearly every infrastructure project around. The Seattle Streetcar is fairly unique in being singled out for the chopping block, however.

A $410 million streetcar project does not look so pricey in the context of the Sound Transit board adding approximately $700 million to West Seattle Link’s tab just so West Seattleites won’t have to look at an elevated guideway, or deal with quite as much construction work on the surface. The elevated Fauntleroy option the tunnel alternative replaced is actually projected to attract higher ridership due to its more central location.

Center City Streetcar ridership boon

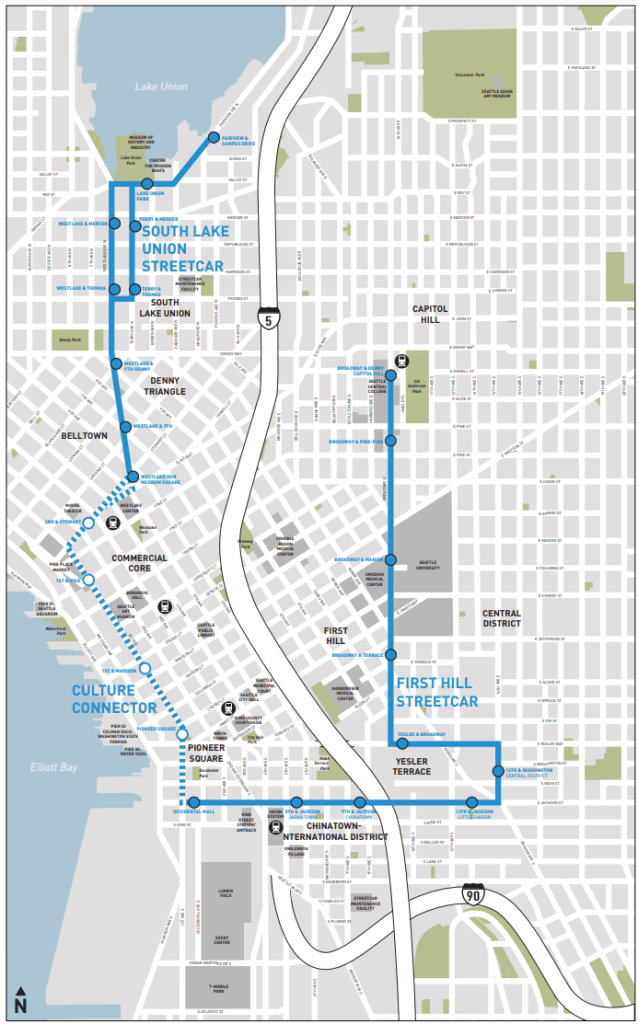

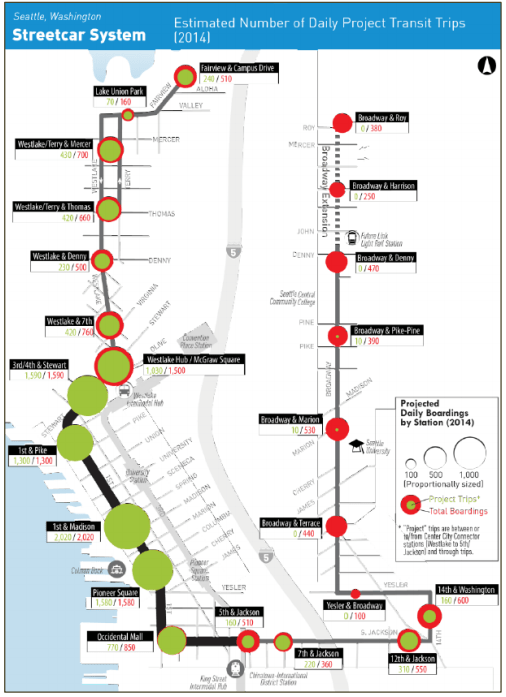

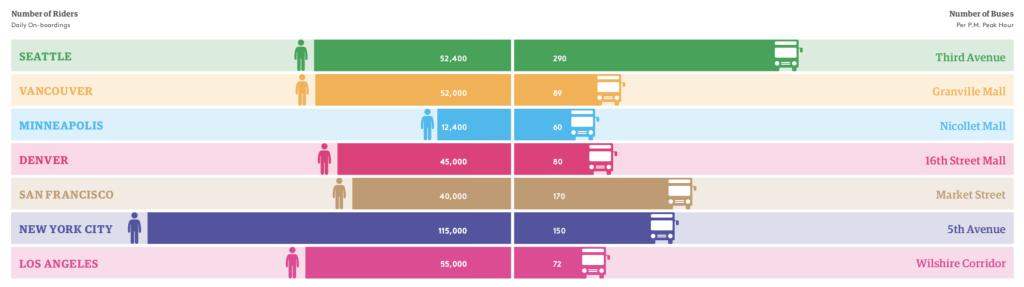

The First Avenue extension would vastly improve Seattle’s streetcar network, providing a major boon to ridership. With the extension, Seattle’s streetcar network could attract nearly as much ridership as the $7 billion West Seattle light rail project is predicted to attract.

“By SDOT’s own estimate, the proposed Culture Connector extension would attract 28,000 daily riders, making it more popular than the busiest bus line in the city,” the transit advocacy group Seattle Subway wrote in their letter-writing campaign seeking to save the streetcar.

While SLU Streetcar ridership is dwindling and low, the First Hill Streetcar has rebounded from the pandemic with some momentum. The 2.5 mile line was hovering around 4,000 daily riders for much of 2023. At 1.2 miles, the SLU line is too short to be very useful, a problem which extension into the heart of downtown and Pioneer Square solves.

The First Avenue extension is a serious transit project with real benefits, not the kind of frivolity that should be killed on a whim as a footnote to an already convoluted City budget by councilmembers scarcely up to speed on the implications. A connected five-mile streetcar network makes sense. Two disconnected shorter lines don’t — and they can only survive so long without the crucial missing link in the middle.

Third Avenue streetcar would offer far fewer benefits

Late-breaking ideas put forward by Councilmembers Kettle and Dan Strauss to reroute the Center City Streetcar on Third Avenue as some sort of urban makeover tool show how little they understand this project and what it means for transit riders and a fast-growing downtown searching for an economic boost.

The Center City Streetcar would added dedicated transit lanes on First Avenue, increasing transit speed and reliability while creating a more walkable street in the process. It would improve transit access on the waterfront side of Downtown, which has scant transit service and a steep hill up to the rest of downtown.

The steep grade to reach the Third Avenue bus mall can be daunting for people with disabilities, kids in tow, or heavy loads. The streetcar provides a way to transverse the hill and disabled Seattleites have noted level boarding and a smoother ride is a big plus, providing an accessible option that upgrades their mobility.

In contrast, a Third Avenue streetcar route would provide far fewer benefits, not creating a new way to navigate the steep hill separating the waterfront from the heart of downtown. It doesn’t expand how many Seattleites would live or work within a short walk of frequent transit, since it doubles down an already transit-rich corridor instead of pioneering a new one. A Third Avenue streetcar would get gummed up in bus traffic and fail to boost transit speed and reliability as much as dedicated First Avenue lanes.

Basic geometric questions appear unanswered. The Third Avenue route would would almost surely mean abandoning the existing First Hill Streetcar stop at Occidental and Jackson Street, since the turn for Third Avenue comes before this stop. In other words, Pioneer Square would lose its streetcar stop. It’s also not clear this back-of-napkin proposal has even answered the basic feasibility question of whether the grade up Third Avenue is too steep to accommodate streetcars.

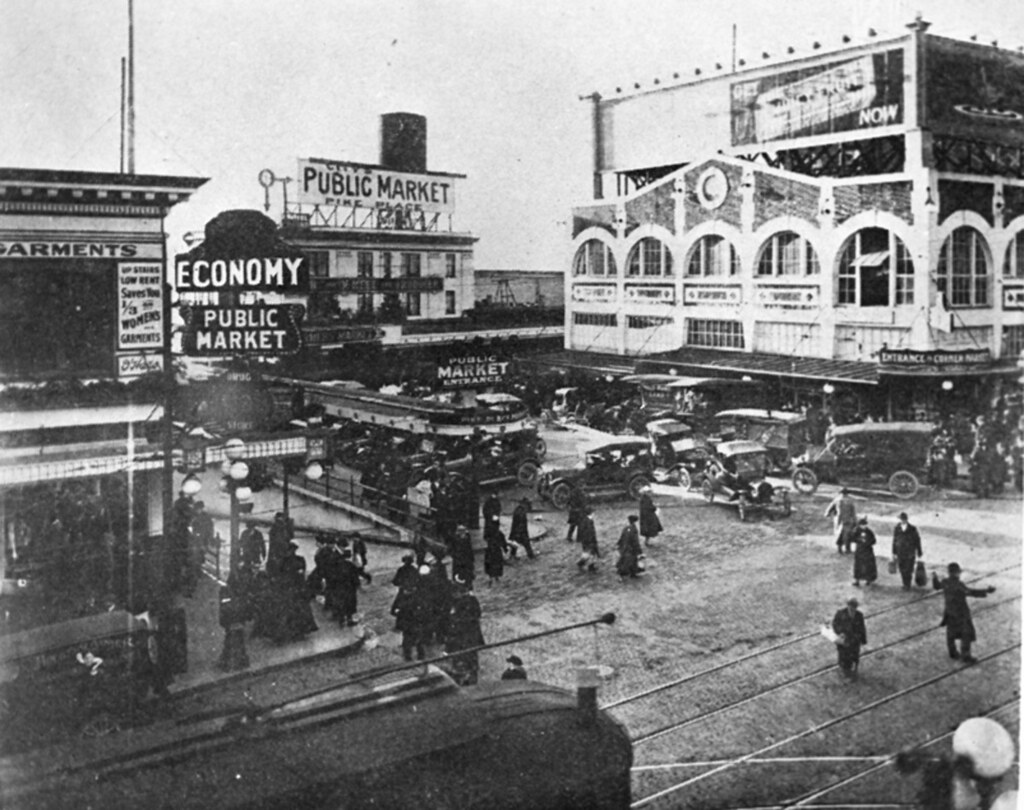

Restoring Pike Place Market’s historic streetcar condition

Leaders from the Pike Place Market have come out hard against the streetcar project. There’s certainly an irony in its historic commission fighting the streetcar when streetcars ran down First Avenue when the market was founded in 1907. Apparently historic preservation is only good up to a point — typically the point it challenges car culture and parking convenience.

A few parking spaces are not going to make or break market vendors, but a streetcar extension projected to exponentially boost ridership passing right by the market would clearly be a draw, bringing in more patrons. It’s too bad Market leaders have been too short-sighted to recognize this long-term benefit.

Seattle needs to stop vacillating

Back before years of inflation and indecision when the project still cost around $200 million, the City had a $75 million federal grant lined up for the project. Later Seattle lined up a $7.3 million federal grant to update project plans, which the Seattle City Council decided to forfeit. Seattle is leaving money on the table with its vacillating, penny-wise, pound-foolish approach.

The argument for the streetcar is not that it’s most important project to improve mobility in Seattle. It’s not. But it is the kind of solid, beneficial project that competently-run cities should carry out as a matter of course. It should be routine rather than a decade-long debate. The failure to build rapid transit projects (and enough housing at all income levels around them) on anything approaching a reasonable timeline is part of why people lose faith in politicians and the cities they run.

Abandoning the Center City Streetcar is shrinking from leadership and imagining a dimmer future for Seattle. Why choose to sabotage our own infrastructure projects and chase harebrained schemes or directionless austerity when we have highly beneficial shovel-ready projects right before us?

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.