Even with upzones in 30 new hubs and the half-block along transit lines, Seattle will keep parking mandates across much of the city.

Tucked into Seattle’s Tangletown neighborhood, south of Green Lake, is a nondescript seven-unit apartment building. Built in 1948, the building includes no off-street parking spaces, taking up most of its 4,600-square-foot lot. With a Route 62 bus stop directly at its doorstep, residents living here can utilize 15-minute service to either Roosevelt Station in one direction, or Wallingford, Fremont, and Downtown Seattle in the other, seven days a week. Just across the street is a fourplex, built in 1951, that also features no off-street parking spaces.

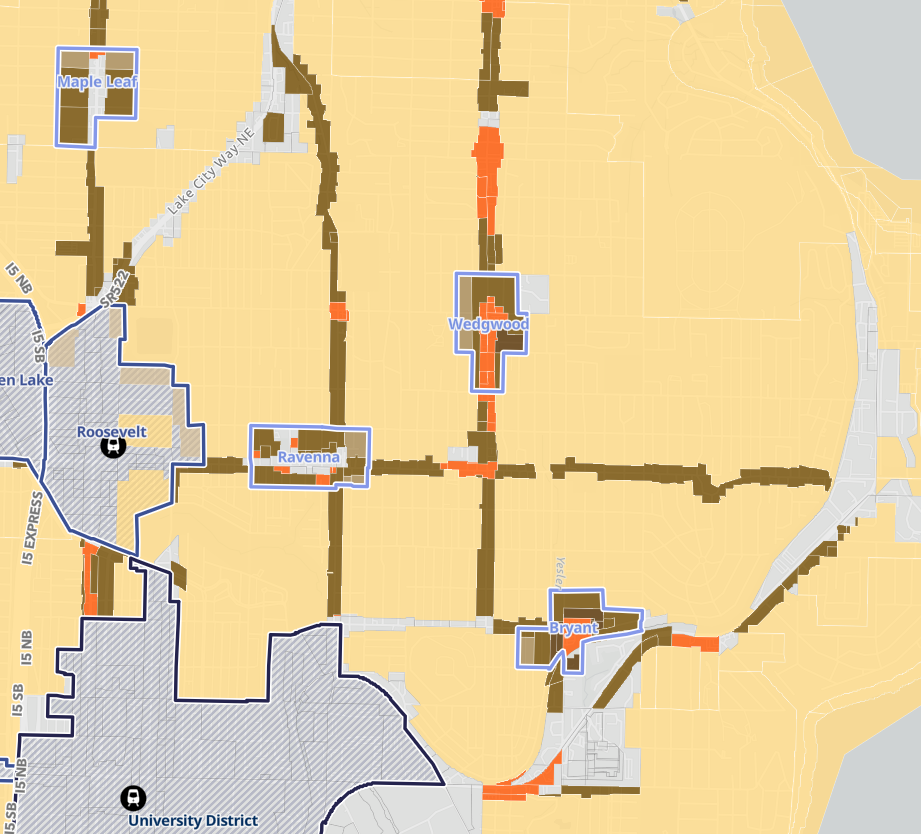

Neither the inconspicuous seven-unit apartment building nor the fourplex could be built today without that off-street parking, nor will they become legal to build under the proposed changes to housing regulations that the Seattle City Council is set to consider next year. New “neighborhood centers” intended to anchor communities will continue to mandate parking if they densify, regardless of how frequent the transit service is at their front doors or the actual needs of future residents.

The fact that the City of Seattle intends to keep parking mandates that could impede housing growth was a footnote as the City released new zoning maps last month, as part of the latest update to Bruce Harrell’s One Seattle Comprehensive Plan. This bucks a nationwide trend of ditching minimum parking requirements, with cities like Austin, Portland, San Francisco, Spokane, and even Port Townsend, Washington already having moved to do so.

It also represents a stalling out for Seattle, which has long been at the forefront of parking-related housing reforms.

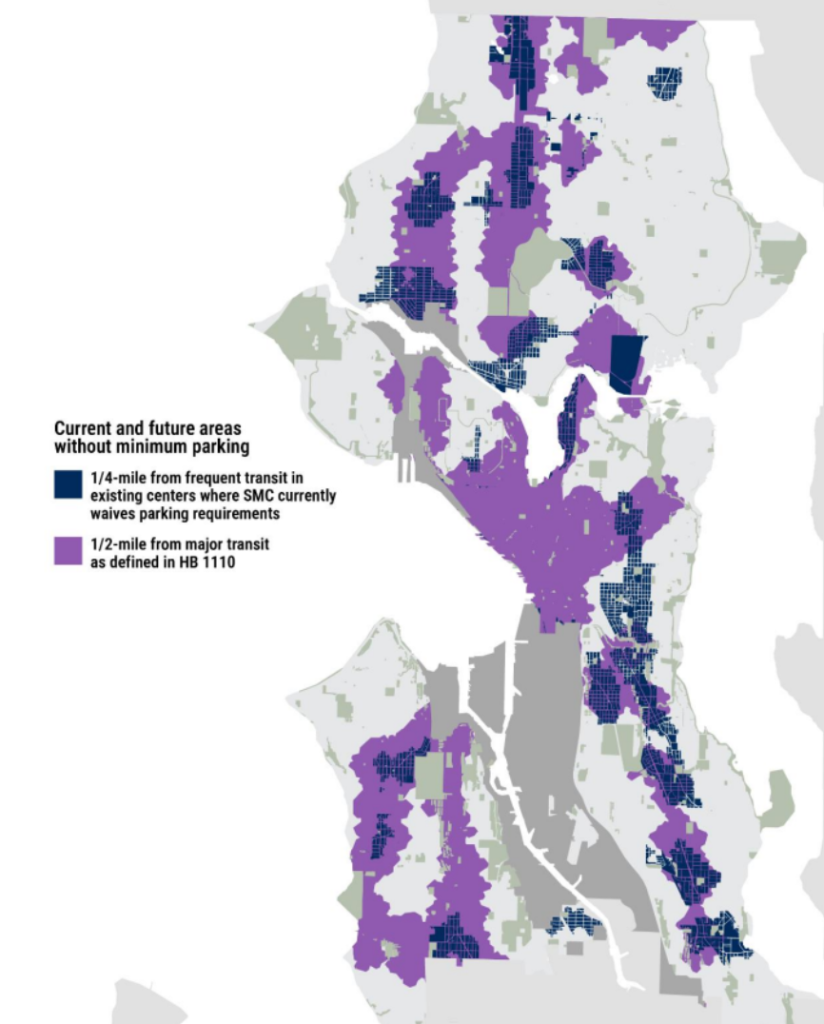

Thanks to reforms passed in 2012 and reinforced in 2018, areas of Seattle within a quarter-mile of frequent transit and within existing urban centers currently have no minimum parking requirements, a fact that wouldn’t change.

Under Harrell’s proposal, the only additional places where required parking would drop to zero are the areas directly covered by statewide parking reform passed in 2023 as part of House Bill 1110, which requires cities to remove mandates within a half-mile of “major transit stops.” Major transit stops under the law include light rail stations and stops along RapidRide bus lines, but aren’t actually tied to frequency of transit or travel times to major destinations.

But outside those areas, requirements would only be lowered to one stall for every two units, where in most cases the existing requirement is a stall for every unit. This would apply to the city’s new middle housing regulations, which are set to allow four to six units on all lots across the city, but also to the 30 new “neighborhood centers” proposed, which include places like Tangletown, North Magnolia, and central Beacon Hill, where more units would be allowed.

Even developers wanting to build along frequent transit lines outside urban centers, where the city is set to allow six-story buildings in the half-block directly along bus lines, would need to include one stall for every two units they build. Bizarrely, even though the land use code will remove many of the special provisions that exist just for accessory dwelling units (ADUs), instead treating them the same as other types of units, they will remain exempt from parking requirements citywide.

Parking requirements are set to add a significant cost to adding new units in the city’s brand new neighborhood centers. A surface parking spot might cost $20,000 to $30,000 to build, but it often replaces trees and green space — or more housing. Meanwhile, a multilevel parking garage might incur costs of $60,000 or more per stall, according to Sightline Institute. Mandated parking also adds a significant logistical barrier that will orient the design of buildings away from what makes sense for residents, and toward what makes sense to accommodate their cars.

“Parking is the first thing that architects plan for,” Matt Hutchins, founding principal at CAST Architecture, told The Urbanist. (Hutchins also serves on the Seattle Planning Commission, which has been breaking down the draft zoning changes over this year and is set to issue a new report in the coming weeks.) “We go through zoning, and then we figure out how to park whatever the number of units that we can possibly do, and that’s before we have a shape of a building because parking is so inflexible, so immutable that you have to start with that, otherwise you’ll never fit the parking that’s required.”

In its interactive zoning map, the Seattle Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) even used the Shea Apartments on 19th Avenue E in Capitol Hill as its example of what would be allowed under the city’s new transit-oriented zoning, except there’s just one problem. The Shea Apartments includes 32 units, but only 12 parking stalls, lower than what would be mandated across most of the city. What policy goals would be served by arbitrarily mandating another four stalls is unclear.

“The difference between having zero parking spaces and having one parking space might be that there’s 1,000 square feet of extra paved area,” Hutchins said. “It has an outsized effect. And many, many places have demonstrated that that not requiring parking doesn’t mean that developers won’t provide it when they can or want to.”

Nationally, Seattle has been a model for what can happen when cities reduce parking mandates to achieve the twin goals of reducing housing costs and encouraging walking, biking, and transit. A 2020 study looking at the results of the 2012 parking reforms that eliminated mandates near transit in urban villages found that 18,000 fewer parking stalls were built over five years than would have been required otherwise, saving more than a half a billion dollars in building costs.

The Parking Reform Network (PRN) has been touting Seattle’s success in implementing parking reform for years, including the gains the city saw in the area of ADU production after dropping parking requirements, along with reforming other regulations for that housing type, in 2019. But it doesn’t look like Seattle is set to join PRN’s map of 89 cities around the world that have gone the full mile and ditched mandates entirely — at least not any time soon.

“These mandates are just going to be a barrier to any other climate, transportation or housing policy fix that you try in your city, to some degree,” Tony Jordan, President of the Parking Reform Network, told The Urbanist. “It might be less at 0.5 [per unit], but there’s always going to be some projects that don’t get done or fail or don’t deliver as much housing, because of these mandates.”

In releasing its updated zoning regulations, City of Seattle staff touted the reduction in required parking from 1 space per unit down to 0.5 as a step forward that will allow builders more flexibility, especially when it comes to uniquely-sized lots. But keeping mandates in place, particularly near some of the city’s most frequent transit lines, cuts against best practices and suggests that the city is spinning its wheels when it comes to housing reforms.

“It’s true that less is better. I often will say, I feel kind of like a doctor: people will come to me and they’ll ask me to justify, or to say, ‘Yeah, you did a good thing by lowering your mandates to half per unit, as opposed to one,'” Jordan said. “That would be like someone coming to me and saying, ‘Yeah, man, I’m smoking two packs of cigarettes a day, and I cut back to one pack of cigarettes a day.’ And it’s like, that’s a good job. The right answer is, no cigarettes a day.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.