The City of Bainbridge Island is grappling with its long-range plan, as the bedroom community and popular tourist destination continues to become increasingly unaffordable for lower-income residents. With a mandate to add nearly 2,000 homes through 2044, the city’s commercial centers could see major changes, including significant growth within Winslow, the island’s primary downtown.

The City’s ultimate goal is to make housing in Bainbridge Island more affordable, but the idea of adding more residents to an island city is receiving a fair amount of pushback from existing residents.

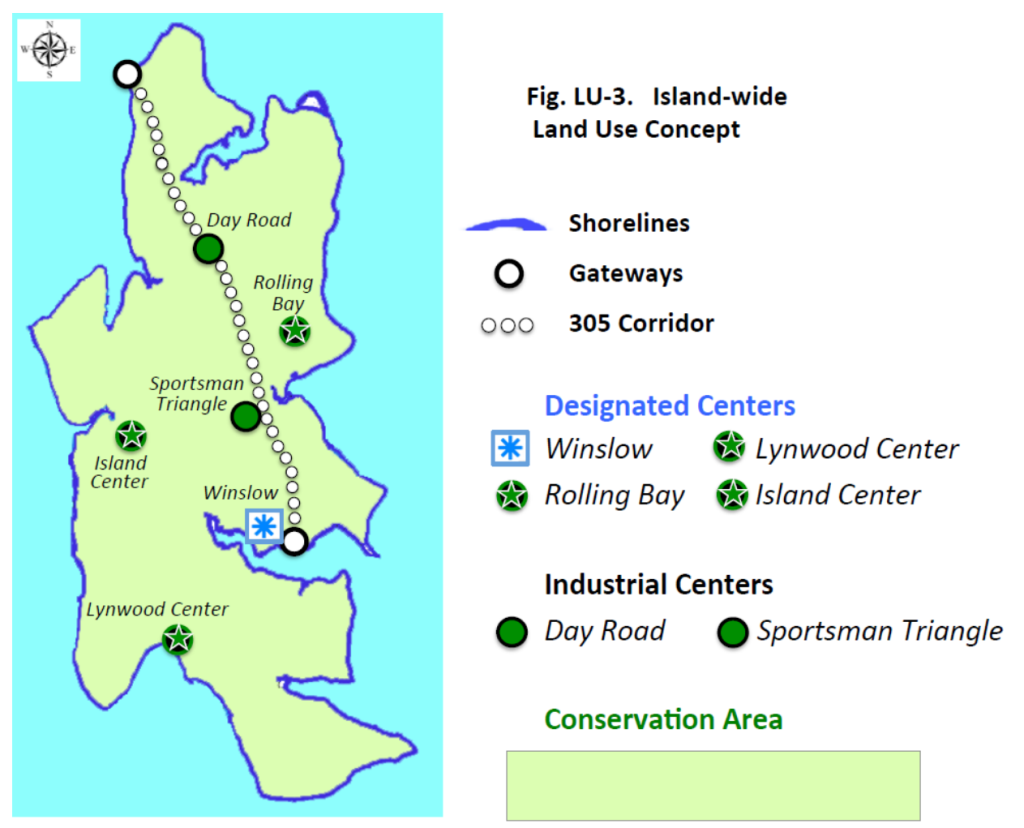

As Puget Sound cities go, Bainbridge Island is a bit of an anomaly. In 1991, the 1.5 square mile City of Winslow annexed the rest of the island, making it one of the most spread-out municipalities in Washington. At just over 25,000 people, the nearly 28-square-mile Bainbridge has approximately the same population as Kenmore, which only spans around 6 square miles. The 1991 annexation vote was originally intended as a way to manage anticipated growth and treat the island as one community, rather than let Kitsap County government manage the island’s periphery. In a telling move, the City of Bainbridge Island refers to the single-family zones that dominate the island as the “conservation area.”

With some of the highest housing costs in Kitsap County, Bainbridge is increasingly becoming a city for older, wealthier residents. Between 2000 and 2020, the median age of Bainbridge Island residents increased from 43 to 50, with 35% of current residents aged 60 or older as of 2020. The share of family households with children declined from 49% to 35% over the same timeframe. Many employees at the businesses frequented by tourists hopping on ferries from Seattle have been pushed out of the city, and many commute from elsewhere in Kitsap County.

Last year, the City adopted a Housing Action Plan, with a clear goal of producing more diverse types of housing and increasing the supply of housing available to people with low and moderate incomes.

While the city has seen some multifamily development in and around Winslow in recent years, new single-family development still vastly outpaces denser development. From 2019 to 2023, the city saw around 125 new multifamily units permitted compared to close to 350 single-family permits, according to data from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development.

On paper, Bainbridge Island has space to accommodate its county-mandated housing growth target — of 1,977 units — with room to spare. But thanks to House Bill 1220, a law the state legislature passed in 2021 that requires cities to specifically plan for the expected income levels of future residents, Bainbridge will have to rezone more of the island to accommodate denser housing that’s more attainable. Given the higher incomes of existing residents, over 1,400 of those 1,977 units have to be targeted toward people making relatively modest incomes or below.

Two paths: Dense centers or distributed density

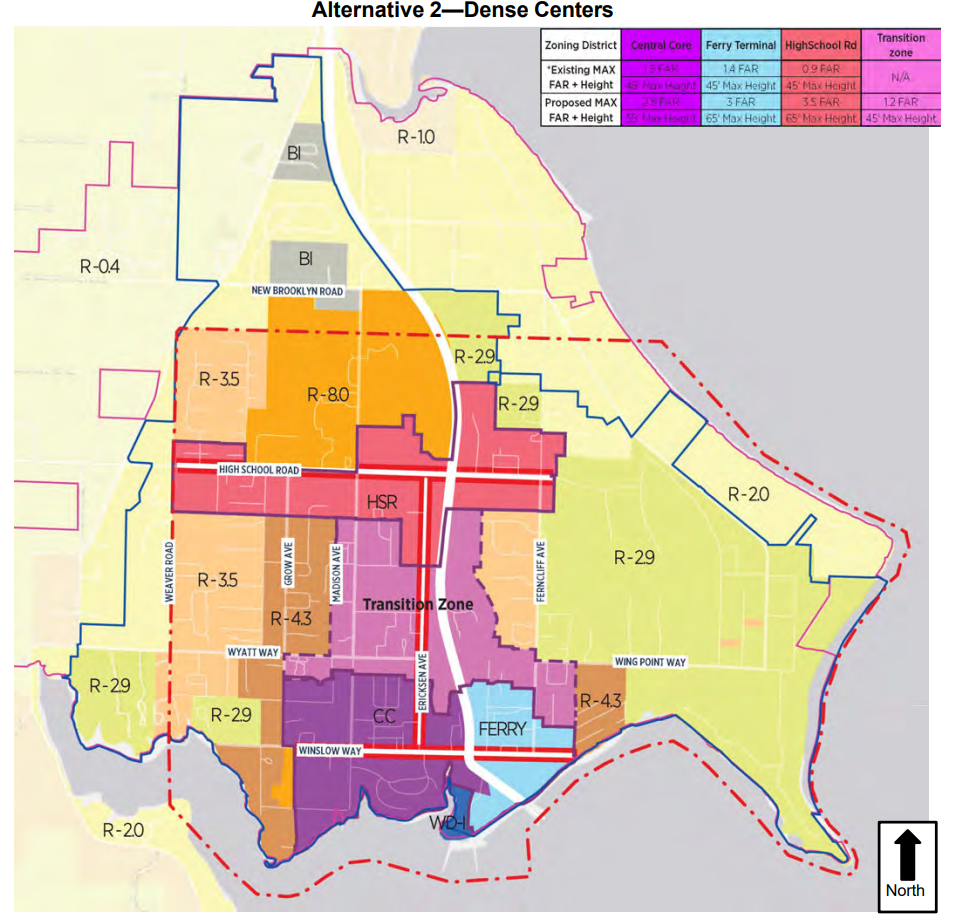

Now it’s up to the Bainbridge City Council to decide exactly how to densify to comply with state law. Earlier this year, the City released a Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) looking at two potential growth scenarios: one labelled the “dense centers” options and the other “distributed density.” Under the dense centers scenario, Winslow would see the most significant zoning changes to accommodate new development, with modest changes to Bainbridge’s satellite urban centers of Lynwood, Island Center, and Rolling Bay.

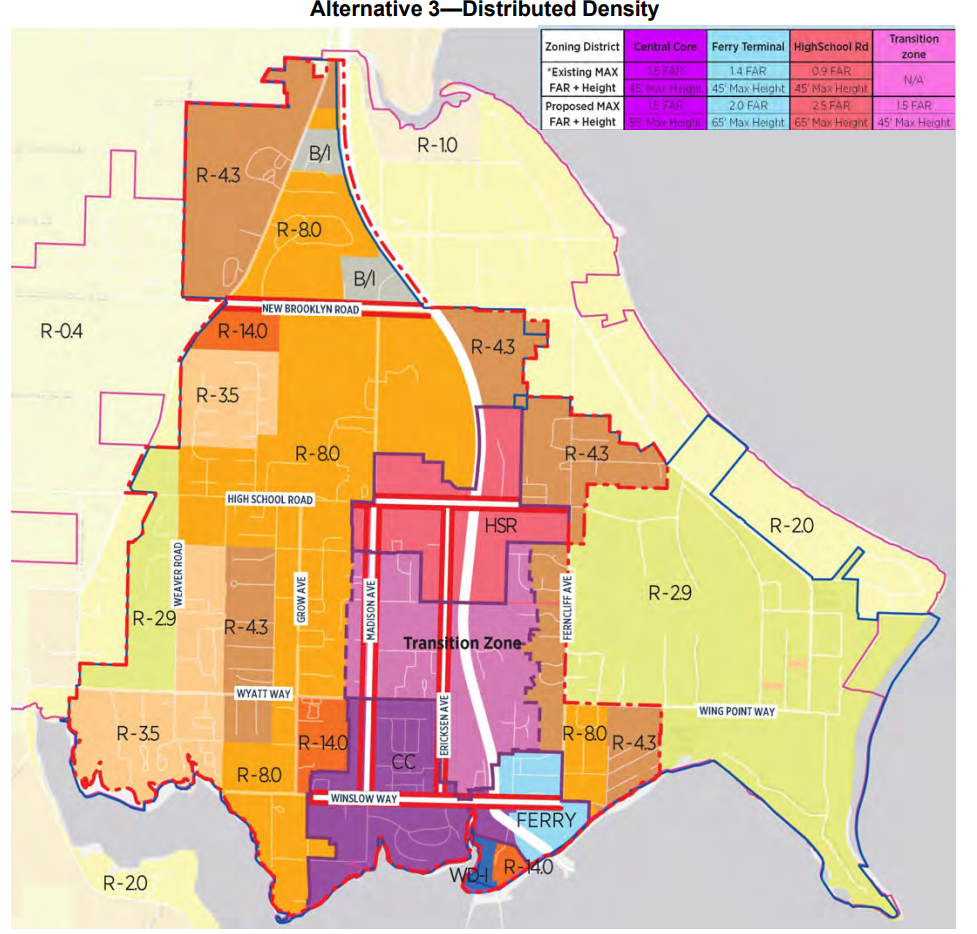

Under the distributed density scenario, those satellite centers would see more substantial changes. Currently Lynwood Center on the island’s south end is a small commercial hub, featuring a movie theater, an inn, and a few restaurants and other service-related businesses.

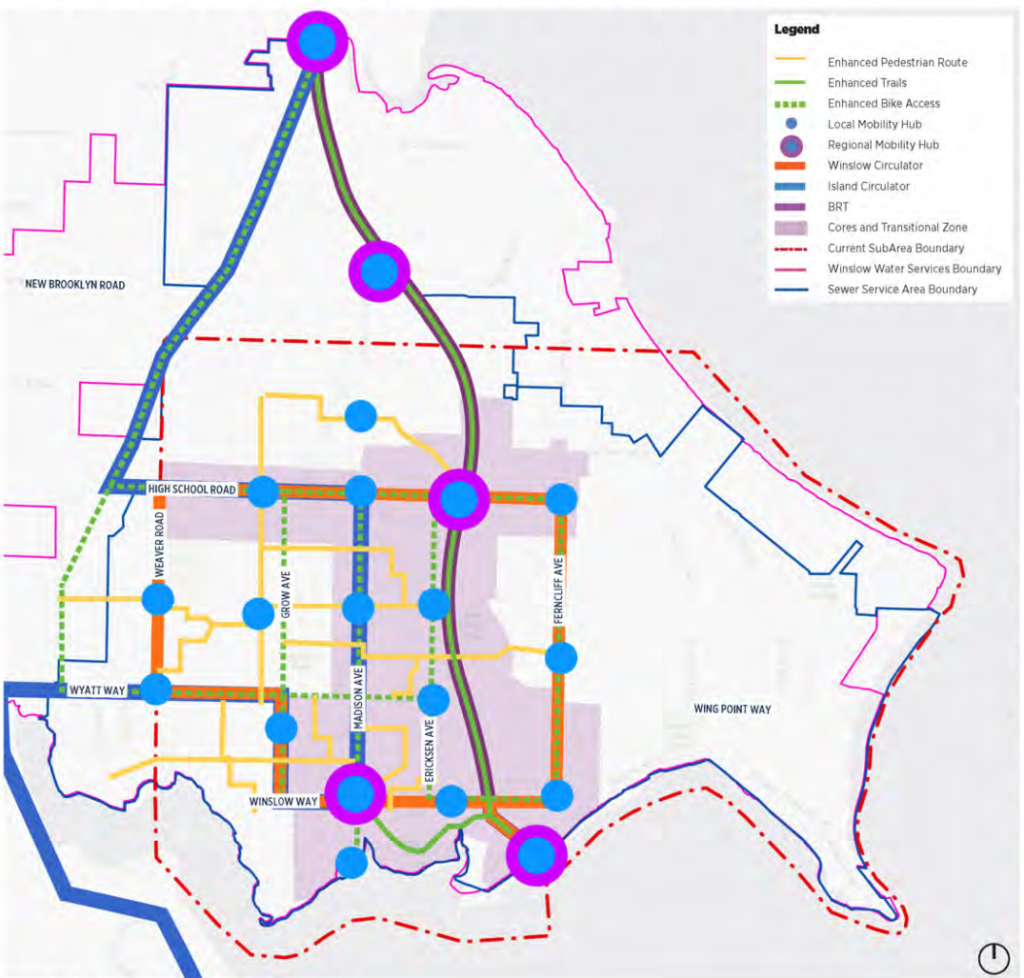

Increasing housing and amenities near the commercial nodes throughout Bainbridge aligns with the strategy that the city adopted in its 2022 Sustainable Transportation Plan, which prioritizes creating multimodal connections to the same centers, making it easier to meet one’s daily needs without a car.

As for Winslow, height increases under the distributed density option would be less intense and the overall neighborhood’s boundaries would shift further into the so-called conservation area, a framework that would encourage the neighborhood to grow out rather than up. That would put new residents further away from services and make trips more likely to be made by car.

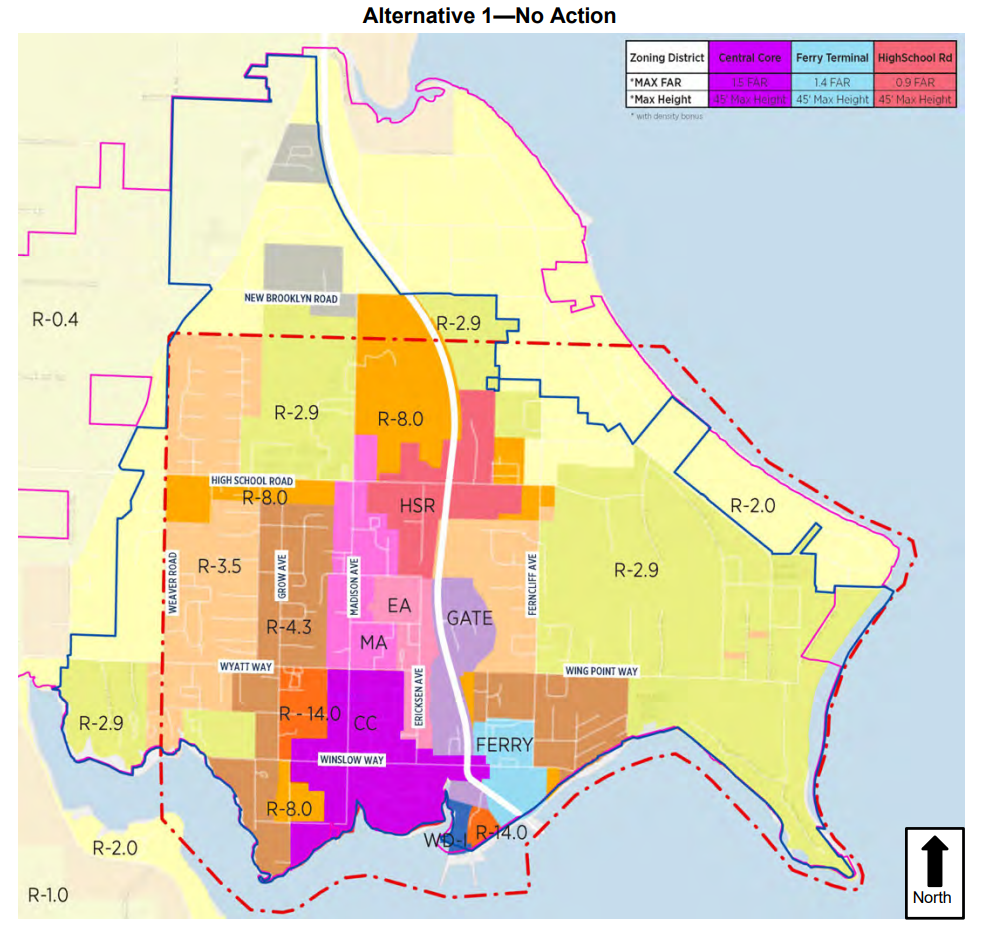

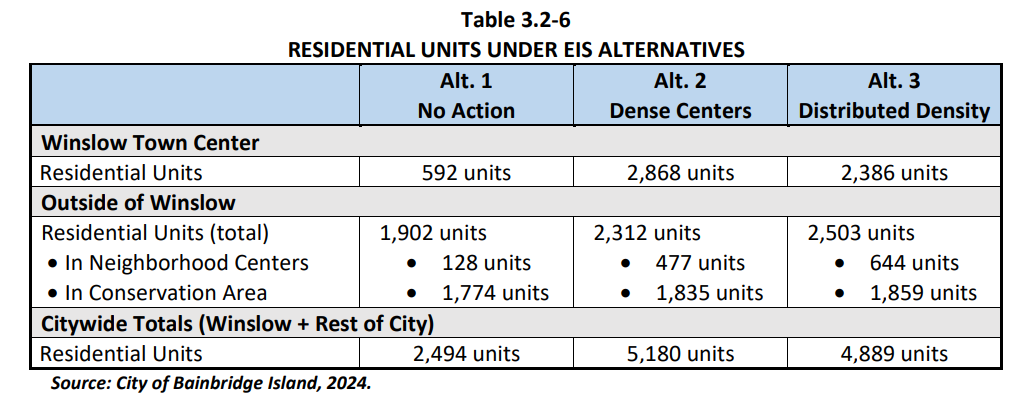

Many Bainbridge Island residents are pushing for a third, status-quo oriented option, included in the DEIS as Alternative 1. Under that option, no zoning changes would occur and the city would continue on its current trajectory, with capacity for 592 units within Winslow and only 128 units in the other neighborhood centers. But city planners call that action infeasible given the state direction coming in the form of HB 1220, to say nothing of the city’s Housing Action Plan.

Comments pushing back on more density on Bainbridge were plentiful during the city’s long comment period on the DEIS, which stretched from late July to early October.

“We don’t want to lose the funky, small town feel of our island. If we want a city experience, we walk on the ferry and go to Seattle. When we come back to Bainbridge, we always take a deep breath and relax, having escaped from the big city life,” Bainbridge residents Jane and Steve Hannuksela wrote during the comment period. “However, the need for more affordable housing is a very real concern. We urge the City to approve increased affordable housing units within the current zoning parameters.”

Those comments were far from the overwhelming majority, though.

“Although we support an increase in density around Winslow, we also believe that more affordable housing around the island would make the island a better place to live. It would made our neighborhoods more diverse and attract young couples who are more likely to have children which in turn will help increase school enrollment and lower the average age of those who live here,” David Danielson, co-owner of Eagle Harbor Books, wrote. “As owners of a retail business, our business model of necessity limits us to seek employees that can afford to work at or near the minimum wage level yet the island has almost no housing that those potential employees can afford.”

Big changes coming to Winslow under either alternative

As Bainbridge’s main commercial district and a portal to the rest of the region via the 35-minute ferry to Seattle, Winslow would see significant changes to its zoning under either alternative. Currently, Winslow has capacity for 592 units of housing, an amount that would increase to 2,386 under the distributed density alternative and 2,868 under the dense centers option — an increase of 303% to 384%.

Focusing development capacity under the dense centers option would mean height limits near the state ferry terminal would rise from 45 feet to 65 feet, the same area where the city is developing a 100 units of affordable housing on the site of a former police station. Another 65-foot zone would take shape further inland, along High School Road. Along Bainbridge’s “main street” and major tourist draw of Winslow Way height limits would be increased but only to 55 feet, with a “transition zone” (paired with a 45-foot height limit) filling in the area in between.

With additional density, Bainbridge would plan transportation investments including an expanded sidewalk network, protected bike lanes — like the ones taking shape on Madison Avenue right now — as well as a potential circulator bus that would shuttle visitors and residents around Winslow. Kitsap Transit’s long-range plan calls for a bus rapid transit (BRT) line along SR 305 between Winslow and Poulsbo, transit service which would parallel the planned extension of the Puget Sound to Pacific multiuse trail set to eventually stretch all the way to La Push on the Pacific Coast.

City council leans toward “bare minimum”

This fall, the Bainbridge City Council is set to select a preferred growth alternative, almost certainly some sort of blend of all the options studied. But so far, several councilmembers have signaled that their north star isn’t a growth plan that will meet the city’s own goals around making the city more affordable, but what will check the boxes to comply with state housing mandates.

“I believe — I don’t know if we’re all there, but I think a lot of us are, and I think the community is — we want to comply with [HB] 1220, with the minimum amount of increased capacity possible, as long as we have the infrastructure, or know we can create the infrastructure in the right time, period,” Councilmember Kristin Kirsten Hytopoulos said at an early October study session on the topic. “And we don’t want a plan that doesn’t do that. I believe that’s our number one goal.”

At the same meeting, Bainbridge Island City Manager Blair King reiterated this point.

“One suggestion that we heard is that the Council should direct the Planning Commission to work with [the growth targets] at the legal minimum, and that the legal minimum should be addressed, and the focus should be on the legal minimum,” King said.

Not everyone is down with that plan. During the DEIS comment period, Bainbridge Island’s own Race Equity Advisory Committee pushed back on settling for a minimum.

“Given the current median income and cost of housing on Bainbridge, we should be ashamed that our leaders would seek the bare minimum in capacity to theoretically meet affordable housing goals, as required by the State of Washington,” the committee wrote. “Demanding the minimum amount of capacity would not yield the number of affordable housing units needed to meet your established goals. Based on these comments, we are left with the troubling impression that the Council may not fully support equity on the Island.”

Ultimately, the status quo doesn’t look to be an option for Bainbridge Island. The question set to be answered in the coming months is whether the city’s leaders will rise to meet the moment or whether they’ll go along begrudgingly, a move that likely won’t fully set the city up for success in the coming decades, and may not be enough to stem the tide against housing unaffordability.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.