At-large Seattle City Councilmember Tanya Woo is seeking to defend her appointed seat in the November 2024 election, and she aims to represent working-class communities like the Chinatown-International District. She has made housing and tackling rising cost of living as the second highest priority campaign issue this year.

“Seattle needs more housing that fits the varied needs of our community,” Woo wrote on her campaign priorities page. “I know firsthand what this looks like. My family transformed the historical Louisa Hotel in the Chinatown-International District into apartments that serve Seattle’s workforce. Here, residents pay only what they can afford. We need more housing like the one my family built, housing that is more affordable and geared towards those that need it most.”

However, current and former tenants of the Louisa Hotel dispute that characterization and claim the building has been mismanaged and failed to meet their needs.

“Like many folks who are houseless, slumlords like Tanya Woo are why we become homeless,” tenant Dean Kubota said. “She is actively creating the problem she claims to solve.”

The Woo Family’s Real Estate Empire

Woo’s family has longstanding ties to Chinatown and Beacon Hill neighborhoods. Tanya’s grandfather Yuen G. Woo immigrated from China as a teenager and later ran a successful Chinese restaurant in Wallingford. Yuen used the proceeds from his restaurant to purchase an 18-unit apartment building in the nearby neighborhood of Beacon Hill. Yuen fathered two sons: Paul and Jack Woo. Tanya’s father Paul became a lawyer and hosted his law office out of the Louisa Hotel building, a property he purchased in 1963.

Paul Woo also incorporated a company known as the Transpacific Corporation within the same building. His brother Jack and his wife Anita worked as employees of the enterprise to build the business. The company primarily existed to manage properties, and to invest within commercial and multifamily real estate.

Paul died in 1997, and Tanya and her uncle Jack later inherited the Transpacific Corporation.

The corporation wasn’t the only way the Woo family held real estate. Tanya’s mother Anita Woo owns or co-owns at least 10 different rental investment properties, excluding The Louisa Hotel. Anita Woo primarily acquired these properties (mainly single-family homes located in the Seattle suburbs) through purchasing them following foreclosure auctions. The rest of Anita Woo’s portfolio includes two duplexes based in Renton and a small apartment building located in Beacon Hill. All told, the Woo family owns 21 different residential properties with an estimated value of $33,425,000.

Jack and Tanya Woo likely used the inherited real estate holdings to help finance the redevelopment of the Louisa Hotel into “workforce housing,” primarily for single adults and couples with low to average incomes. They partnered with a local nonprofit known as the Seattle Chinatown International District Public Development Authority (SCIDpda) for financial and logistical assistance repairing the property, which suffered severe damage due to a fire in 2013.

The Woo family partnered with Valerie and Greg Gorder of Gaard Development and with the firm Impact Capital, a nonprofit private equity company based in downtown Seattle. These business relationships enabled the Woo family to secure over $17 million of financing from the First Federal Savings and Loan Association, as well as financing from a subsidiary of JP Morgan Chase bank.

Woo’s Political Rise

Beyond funding the restoration of the aging historic property, the workforce housing move also provided Woo with a selling point for her personal political narrative, not to mention more clout in political circles. Woo leveraged her family’s experience with financing “workforce housing” to ingratiate herself to Seattle City Councilmember Sara Nelson, who endorsed a slate of centrists hoping to wrestle control of council from progressives. Tanya also won the backing of lobbyist and local political powerbroker Tim Ceis, whose clients include Amazon and some of the biggest developers in the region.

In 2023, Woo was running in Council District 2, which covers Southeast Seattle and much of the International District, against incumbent Tammy Morales. Despite the whole slate of business-backed centrists otherwise winning, Woo came up short against Morales. Not to be deterred, the new Nelson-led centrist majority on council appointed Woo to a vacant citywide seat created when Teresa Mosqueda won her election to the King County Council in 2023.

Ceis lobbied hard for Woo, and newly-christened Council President Nelson backed Woo’s appointment to replace Mosqueda until the next election. For her part, Councilmember Morales cried foul.

“I am disappointed in how this process turned out,” Morales said in remarks ahead of the vote. “This appointment process should have been set up to give all candidates a fair shake. It should have been about identifying someone who can hit the ground running, someone who can deliver for the entire city. But instead it did become about big business telling donors that they earned the right to tell this council who to choose — and that is deeply problematic and it is anti-democratic.”

During a September 17th Seattle City Council Meeting, Woo expressed concern about “our unhoused neighbors.” She furthermore appealed to her authority as a housing developer. “As an affordable housing provider, we do workforce housing, we charge rent based on people’s income.”

A group of tenants who live within, or recently departed the Louisa Hotel, have come forward to disclose their experiences as beneficiaries of Woo’s “affordable housing.”

Dean’s Story: Respiratory Shock

Dean Kubota moved into the Louisa Hotel in 2019, when the building offered “affordable housing” marketed to working adults with incomes between $35,000 to $80,000 annually. Kubota played the trumpet in jazz bands and sang at various gigs, but they primarily worked as a preschool teacher and nanny to pay the bills.

Kubota initially felt lucky to secure a below-market rate studio thanks to Seattle’s MFTE (Multi-Family Tax Exemption) program, but then they gradually started to feel sick. Brown mold spores proliferated on the walls of their apartment, Kubota said.

SCIDpda contracted with the Louisa Hotel to provide property management services for the building. Kubota said SCIDpda’s effort to abate the mold exacerbated their respiratory distress.

Editor’s Note: A spokesperson for SCIDpda provided the following statement after we went to post: “SCIDpda was invited to comment on this article; however, due to our strict privacy policies, SCIDpda does not disclose any personally identifiable information about past or current tenants. This policy reflects SCIDpda’s commitment to resident confidentiality and ensures the protection of privacy for all individuals within properties we manage.“

Exterminators hired by SCIDpda also visited Kubota’s apartment to eliminate a cockroach infestation. The exterminators wore triple-layered face masks as they allegedly sprayed the aerosolized insecticide known as Nyguard, an acutely toxic respiratory irritant. Kubota said they were not given any kind of personal protective equipment and were not granted sufficient notice from SCIDpda regarding upcoming visits planned by the exterminator.

By 2021, Kubota temporarily moved to another below-market rate studio within the Louisa Hotel to escape the severe allergic reactions and respiratory illness they encountered while living in their first apartment. However, a neighbor with paranoid delusions threatened to kill them and other tenants, Kubota said, and property managers refused to intervene or evict this person.

Kubota had to move apartments again, and finally resided in a studio which overlooked Safeco Field, and featured a small patio suitable for a rooftop garden. Visits from the exterminator to eliminate cockroaches continued, at least within the hallways and adjacent units which Kubota said shared a ventilation system with their apartment. Kubota eventually developed stage-four esophageal cancer and could no longer speak or work. Their disability check from the Social Security Administration barely covers their rent ($1,375 per month) and they have visited the emergency room at least 10 times due to anaphylactic shock.

“Like many folks who are houseless, slumlords like Tanya Woo are why we become homeless.”

Dean Kubota, Louisa Hotel tenant.

A new property management company called United Marketing Incorporated took over the Louisa Hotel during the summer of 2024, and they continued to dispatch the same pest elimination company used by SCIDpda. Exterminators most recently applied insecticide to an apartment adjacent to Kubota’s unit at the end of the first week of September, they said. A week later, Kubota reported breaking out in hives and had to visit the emergency room due to anaphylaxis. That left Kubota effectively houseless and living elsewhere temporarily while their respiratory issues have flared up.

“I had to leave with the clothes on my back and very little else,” Kubota said. “Even returning once made me have anaphylactic shock.”

Skye’s Story: Evicted without a Working Elevator

Skye is a trans woman who moved from Spokane to Seattle during 2020. She survived an abusive relationship and nearly faced homelessness. Skye thankfully found a loving romantic partner and managed to secure a studio apartment located within the Louisa Hotel. She and her partner moved into the unit during June 2023, and Skye described the apartment as one of the nicest places where she had ever lived.

One of the property managers working for SCIDpda went out of her way to cultivate a welcoming environment for tenants through organizing social events, and she ensured that disabled tenants like Skye had the accommodations they needed. However, SCIDpda had a high turnover rate for property management staff, and soon that particular property manager left for another job.

Severe pain typified daily life for Skye. By her late twenties, Skye developed a debilitating disease called Ehlers-Danlos syndrome (EDS), and consequently could not move without the assistance of a wheelchair. She also had fibromyalgia and post-traumatic stress disorder; a mental health condition she said was exacerbated by her neighbor shouting slurs across the hall. He allegedly threatened to kill various neighbors on his floor, and he delighted in clanging cymbals together at all hours of the day.

Skye could not work, and she did not meet the arcane criteria required to receive full disability benefits, so she could not provide much financial assistance to her household. Her partner struggled to work a low-wage job, and had a condition that limited their mobility. The Louisa Hotel’s elevator also sporadically broke down, and Skye was often left stranded in her third-floor apartment. She said they both did their best to pay rent on time, despite SCIDpda staff requiring tenants to pay via check or money order, and not offering an online payment option.

Skye and her partner documented every time they left their money orders for paying the rent with the property management office. The office allegedly lost track of two money orders, and Skye and her partner consequently owed two months’ worth of rent. They started falling further behind on rent, particularly when one of the SCIDpda property managers negotiated a rent repayment plan with monthly payments 50% higher than their typical rent of $1,215, Skye said. The couple’s monthly rent thus increased to $1,800, which she said amounted to almost their entire household income.

Apparently, management did not keep track of their payment schedule, and their remaining rent balance ballooned despite their effort to pay the balance in full.

Shortly thereafter, their neighbor from across the hall hammered several holes into Skye’s door and started screaming slurs specific enough to apply to Skye and her partner. Property managers from SCIDpda helped Skye and her partner move to another studio located on the 4th floor. Skye said she felt much safer, although the windows in her new apartment overlooked a dark alleyway instead of the sunshine from the street.

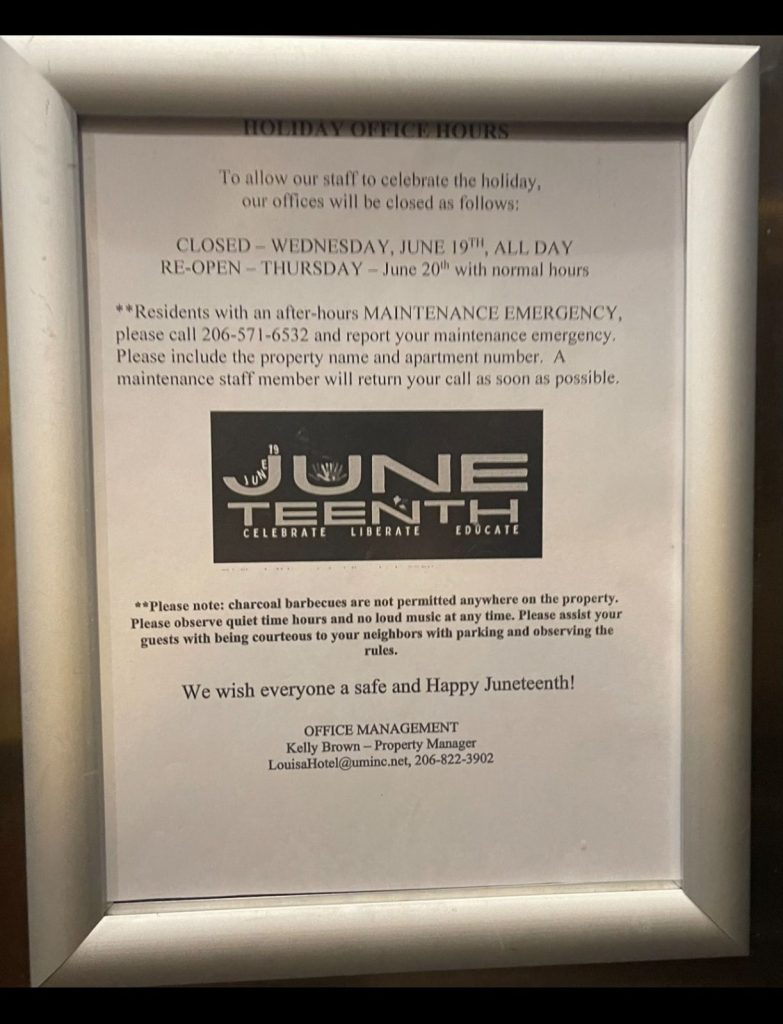

Skye and her partner continued to pay the fee of $1,800 a month as stipulated in the payment plan offered by SCIDpda management. However, the property management changed, which led to yet more trials and tribulations. A company called United Marketing Incorporated now oversaw the building.

14-Day Notices for Everybody

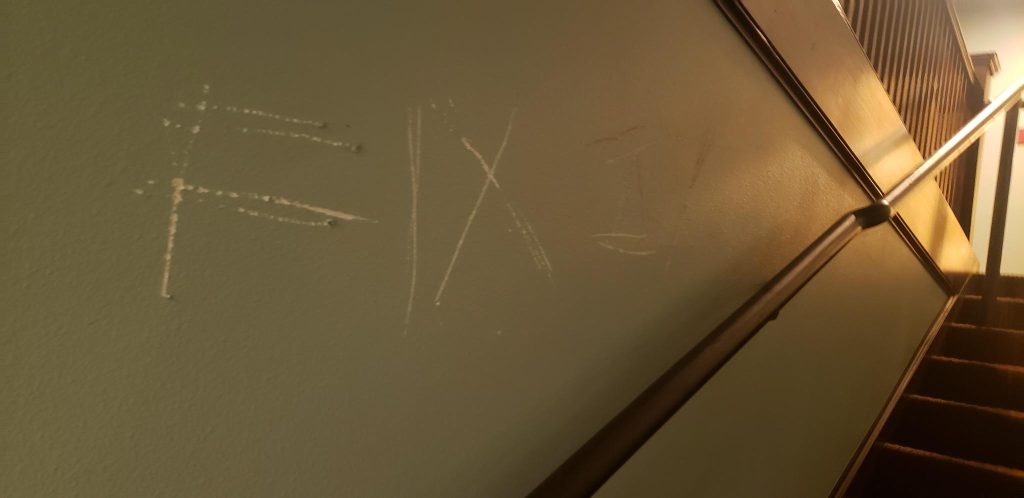

United Marketing took over managing the Louisa Hotel in the summer of 2024. Tenants said the new property manager, Kelly Brown, aggressively tried to collect any outstanding rent owed by the tenants. This task proved difficult since SCIDpda purportedly did not maintain accurate accounting records for rental payments owed and did not transfer payment plans (offered to tenants like Skye) to the new property management company. When in doubt, United Marketing appeared to opt for the eviction route.

Skye felt shocked when she noticed a 14-day pay or vacate notice taped to her door. She said they had paid the full $1,800 as stipulated by SCIDpda’s payment plan for the last 2-3 months, and she thought that good faith effort protected them from eviction.

Most of Skye’s neighbors had 14-day notices as well, even neighbors like Kubota, who had bank statements proving that they consistently paid rent.

“It seemed like they [United Marketing management] wanted to throw one on the whole building, just to be threatening,” Skye said.

She and her partner resolved to move out of the building as soon as possible.

United Marketing did not respond to a request for comment.

The Elevator Saga

That summer, the elevator to the Louisa Hotel broke, and remained out of commission for six to seven weeks, according to Skye’s estimate. Skye and her partner were preparing to move to a cheaper unit down the hill, but the broken elevator forestalled their plans for about a month. Skye remained enclosed in her room and felt more socially isolated than usual.

Moving apartments proved an excruciating process since Skye could not use her wheelchair without a working elevator. She had to painfully and slowly ascend and descend the four flights of stairs leading to the ground floor, aware that any sudden movement could dislocate her joints. Her partner and friend had to lift Skye’s wheelchair and various other heavy objects during the move-in process, but they struggled with their own physical disabilities.

Skye said management did not help Skye and her friends when they tried to move from the apartment, and did not arrange any external help when Skye could not afford to maintain cell service.

Seth Olsen, a neighbor of Kubota, confirmed that the elevator for the Louisa Hotel was broken when he attempted to move into the building during that summer. Olsen is a young able-bodied, White man, and could manage moving into his upper-floor apartment without much assistance. Management from United Marketing still offered to compensate Olsen $250 for his trouble, though reportedly paid him months after his initial move-in date. Skye and her partner received nothing.

David’s Story: Harassment and Toilet Backflow

David Davis is a Black man in his 50s who lived in his pick-up truck for about two years after he moved from Portland to Seattle, days before the start of the pandemic. Prior to his move, Davis spent time as a child in foster care and then spent a stint in prison as a young man. The violence he witnessed or experienced in prison traumatized Davis decades later. A journeyman roofer, Davis did repairs for a local mosque to earn extra income.

Davis heard that below-market rentals were available in the Louisa Hotel. Davis felt overjoyed to move out of his truck and into his own apartment, which he described as “really nice”.

Unfortunately, troubles soon arose between Davis and SCIDpda, the property management company hired to oversee the Louisa Hotel. Davis suffered from alcoholism, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and a gastrointestinal disease which rendered working on jobsites difficult, if not impossible. Davis also described “antebellum” treatment he received on job sites as a Black man, and he refused to tolerate such disrespect. Davis consequently fell behind on paying rent.

During 2023, his toilet malfunctioned, and he said the smell of sewage diffused throughout his apartment, and management from both SCIDpda and United Marketing refused to install a new toilet. Sometimes Davis avoided the smell by sleeping in the hallway outside his unit.

Management from SCIDpda then started posting “unofficial” pay or vacate notices on his door daily. One manager threatened to tow his pickup truck parked in the garage underneath the Louisa Hotel and made evicting Davis and four other tenants “his personal project,” Davis said.

Davis reported that a stranger assaulted him outside the Louisa Hotel during the winter of 2023. Davis was doing artwork outside his building with his scooter parked beside him. Then, a much younger White man tried to take his scooter. The younger man pummeled him repeatedly, Davis said, but he was able to deter him enough to force a retreat to a waiting red getaway SUV. Allegedly, property management at SCIDpda refused to gather footage from security cameras situated in view of the assault and refused to help Davis file a police report.

Reflecting upon his experience at the Louisa Hotel, Davis remarked, “I’m pretty determined to make this a victory story. I want to win.”

Winning entailed not only justice for him and the other tenants, but also adopting more effective coping strategies to heal from the hardship he endured throughout his life. Although Davis characterized the quality and quantity of alcohol rehabilitation services available to the poor as “horrible,” he remained optimistic about his future.

“For me, in my mind, winning is going to treatment, and becoming sober, and non-using, with the application of Zen Buddhism and nonviolent communication,” Davis said.

Woo’s Apparent Conflicts of Interest

Beyond undermining her personal narrative as a virtuous provider of affordable workforce housing, the unfortunate experiences of Louisa Hotel tenants also suggests Woo views housing policy through the lens of a landlord, and likely faces conflicts of interest on legislation relating to tenant rights and housing abundance. Nonetheless, Woo has voted on key housing legislation, including joining the centrist majority in an attempt to block a citizen-led initiative to raise new funds for Seattle’s new public developer of social housing. (Full disclosure: I have volunteered for House Our Neighbors, the group that gathered signatures to put Prop 1A on the ballot).

In fact, Woo even co-sponsored Seattle Proposition 1B, an initiative backed by the Seattle Chamber of Commerce as an alternative to the grassroots social housing measure. Proposal 1B exists to oppose the aims of Proposition 1A, which was crafted with the aim of raising $52 million annually to finance affordable housing via a high earners tax upon Seattle’s wealthiest corporations. Proposition 1A garnered the support of the Martin Luther King County Labor Council, the Seattle Education Association, and The Urbanist Elections Committee.

Backers say Proposition 1A would constitute the first example of social housing on the West Coast, or a mixed-income model of housing funded through a combination of taxes and higher rents charged to renters with higher incomes. Households with 0 to 120% of the area median income (Seattle‘s median annual income surpassed $120,000 in 2024) would qualify for social housing under the proposal, and residents would have more democratic control over the management of social housing properties.

Proposal 1B would not raise any additional revenue for funding affordable housing through taxing wealthy individuals or corporations. Proposal 1B would instead divert $10 million annually from the existing payroll expense tax fund (also known as JumpStart) for a period of five years to finance social housing and the staff needed to sustain the social housing development. This is on top of about $300 million the centrist majority is seeking to divert from JumpStart to plug a $250 million budget deficit in 2025, while still finding money for a big increase in Seattle Police Department funding.

In addition to offering far less money to the social housing developer, Proposal 1B would also force it to compete with cash-strapped nonprofit developers for an already limited source of financing for low-income housing.

Despite Woo’s espoused concern for her “homeless neighbors,” she led the campaign against the expansion of a homeless shelter in SoDo, an industrial neighborhood adjacent to the International District, before she assumed office. In Kubota’s eyes, efforts by “slumlords” to squeeze low-income tenants for more money while providing substandard conditions is a major contributor to rising homelessness, as tenants get trapped in cycles of poverty and housing instability.

Tanya Woo did not reply to a request for comment.

Wayne Barnett, who is the executive director of the Seattle Ethics and Elections Commission, did recommend that Woo recuse herself on legislation pertaining to delivery app drivers, since her family owns a restaurant that uses delivery app services, after Woo reached out for advice. The ethics commission has not interpreted legislation pertaining to landlord-tenant law as strictly, apparently.

“I have not received complaints that [Councilmember] Woo has violated the Ethics Code,” Barnett told The Urbanist. “I received a request for advice from her office earlier this year, and to the best of my knowledge she has complied with that advice.”

While her tenants are not very happy with Woo, the real estate lobby is. The Seattle King County Association of Realtors endorsed Woo for Seattle City Council, and the Washington Realtors political action committee donated $60,000 to back her 2024 campaign. The National Association of Realtors put more than $61,000 behind her 2023 campaign.

In the November 5th general election, Woo faces off with progressive challenger Alexis Mercedes Rinck, who has The Urbanist’s endorsement. Rinck garnered more than 50% of the vote in the primary, suggesting a swell of support for progressives. However, Woo’s wealthy backers are likely hoping to narrow the gap with a campaign spending spree down the stretch to keep a landlord-aligned legislator in power.

Vote: Voters must turn in their ballots at a drop box by 8pm Tuesday, November 5 or ensure they are postmarked by then for their vote to count in this election.

Rachel Kay

Rachel Kay has lived in Washington state for over 10 years. They have a passion for understanding how economics affects the opportunities and constraints available to everyday people. Rachel spends their time engaging in mutual aid projects and volunteering for harm reduction efforts established to help people struggling with addiction. They are a partisan in the “war on cars,” and refuse to own one.