On paper, Greater Bremerton is making some significant steps towards safer streets. The City of Bremerton lists 13 transportation projects, and Kitsap County lists several more, each of which incorporate some bicycle or pedestrian safety improvements. Official planning documents extoll the virtues of a safe and efficient multimodal transportation network.

However, recently completed projects in Greater Bremerton have fallen well short of modern standards for bike and pedestrian safety. The projects fail to shorten crosswalk distances, slow traffic speed, or protect cyclists with more than paint. And both projects incorporate freeway-inspired design elements which improve traffic throughput, but only at the expense of the bike and pedestrian experience.

Below, I’ll discuss two recently-completed projects, which exemplify the inability of local streets departments to design and build safer streets. Bremerton’s tortured city borders mean the two projects – both in the heart of the City, were completed by different governments. The Washington/11th roundabout was built by the City of Bremerton. The West Hills School street safety project by Kitsap County were both touted as street safety projects, but achieved the opposite for people outside of cars.

Both projects incorporate unfriendly street design elements that will increase traffic speed and stressful experiences for people walking and rolling.

Flawed roundabout at Manette Bridge

Bremerton’s new roundabout on Washington Avenue at Manette Bridge could have been a shining gem for the City. Just a five-minute walk from the ferry terminal and leading to the hip Manette neighborhood, the project should have been inviting for tourists and locals to stroll the amazing views off the Manette Bridge. Instead, the City overbuilt the road for cars and crammed cyclists and pedestrians into a narrow eight-foot path.

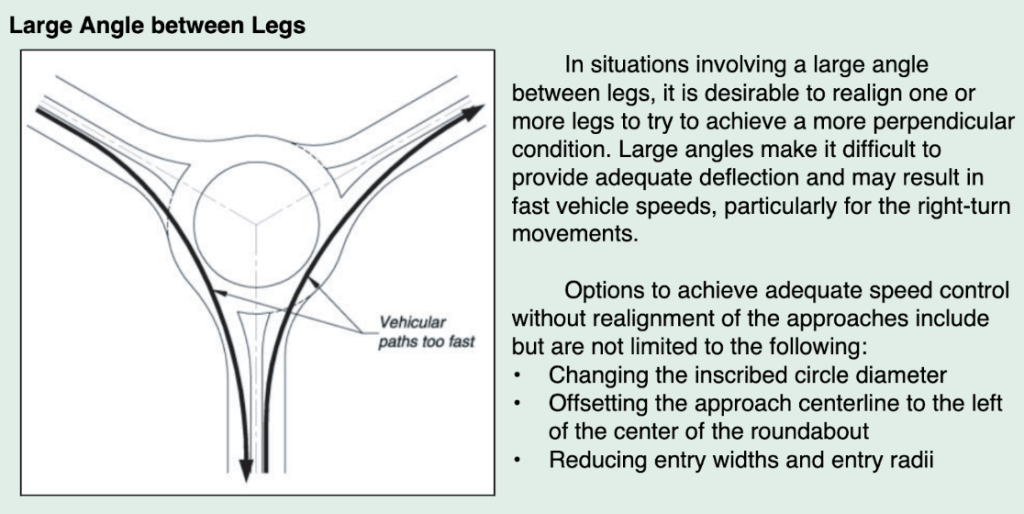

The core flaw of Bremerton’s new $8.4 million Washington Avenue roundabout is bad space allocation – too much for cars, too little for everybody else. At the west end of the Manette Bridge, the new roundabout is more than 75 feet in diameter with lane widths of 16-18 feet, plus a huge truck apron. The three-directional roundabout has very large entry angles, which encourage drivers to speed through.

By luxuriously allocating space to vehicles, the roundabout left precious little space for bikes and pedestrians. Riding a bike onto and off the bridge is particularly fraught. Riding eastbound onto the bridge, the street design forces bikes onto the sidewalk, but there’s no off-ramp to allow them back into the bike lane. Bikes and pedestrians are forced to share a narrow 8-10-foot path over the bridge.

Westbound off the bridge, the bike lane ends suddenly. In place of an on-sidewalk bike ramp, the City built an unsafe stormwater collection booby trap and cyclists are forced to ride in the roundabout.

The new design also failed to remove a guy-wire placed directly in the center of the bike/pedestrian mixing zone. The crosswalk at the western end of the bridge is 40 feet wide, due to 18-foot car lanes.

The City of Bremerton roundabout project failed utterly in the goal Bremerton set out: to “maintain a safe, efficient, and integrated multi-modal transportation system to support a healthy and vibrant community.”

The high-speed school zone

The $3 million West Hills Stem School – National Avenue Roadway Improvements project meant to improve student access and safety for school children, on a high-traffic intersection of Loxie Eagans Boulevard and National Avenue, near a SR 3 highway interchange in West Bremerton. The Kitsap County project failed because it widened the intersection, making crosswalks longer, and included no traffic calming.

To its credit, the West Hills School project built five blocks of a one-way-only, downhill bike lane as well as much needed sidewalk. End of highlights.

Unfortunately, the major intersection of Loxie Eagans and National became less safe for pedestrians. The project widened the crossing distance for pedestrians in all four directions of the intersection. The four corners of the sidewalks at the intersection are cut way back (large turning radius) to encourage cars to turn rapidly through the crosswalks. The key intersection was no delight for pedestrians before construction, but is probably worse now, because of the longer crosswalks and faster car speeds.

Speaking of speed, the entire project is devoid of traffic calming measures, other than a speed limit sign that only recommends that cars slow down when the light is flashing.

The project includes, quite possibly, the worst new bike lane I’ve ever encountered. The bike lane is only five blocks long, and one-way downhill (one-way bike lanes can be useful uphill, because bikes move so much slower). The bike lane spends one block of its five-block length as a terrifying ‘turn pocket’ that forces cyclists to ride between two lanes of cars. Turn pockets increase the “Level of Traffic Stress” rating for bikes and pedestrians and would make the bike lane unrideable for children. No parent who loves their child would allow them to ride in that bike lane.

Why can’t Bremerton get it right?

Both Bremerton and Kitsap County have proven unable or unwilling to build projects that reduce the stress and danger experienced by people walking, biking and rolling. High-quality projects need protected bike lanes, enhanced protection at crosswalks, narrow crosswalks not wider ones, and traffic calming measures to slow traffic, especially near schools. Instead local streets departments design roads with the exclusive pleasure of drivers in mind. I can think of no recent exceptions.

The inability of Bremerton and Kitsap County to build safe street infrastructure is systemic, ongoing and caused by a variety of factors. The region has been building streets the same way for decades, designing streets for rush hour traffic and efficient movement for cars, always at the expense of those who live here and, say, walk their kids to school. Here are some of factors that lead to bad street safety choices in Greater Bremerton:

- Myopic focus on maximum car throughput. Each new project borrows from freeway designs: wide lanes, extra lanes for turning, wide turn radius and ‘turn pockets’ all of which encourage speeding. As a result of freeway-style design, sidewalks are narrowed, crosswalks are lengthened and cyclists are forced into dangerous situations.

- Lack of accountability. Many state and federal streets grants require multimodal improvements such as bike lanes. But there is no system for ensuring that said bike lanes actually improve the level of stress for people walking, biking and rolling. Projects funded with Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) bike and pedestrian or safe routes to schools funding are required to adhere to the WSDOT design manual, but the same isn’t true for grants awarded through the Puget Sound Regional Council.

- Cars for National Security. Bremerton and Kitsap County are home to Naval Base Kitsap, a facility with 36,000 (and growing) civilian and military personnel. Getting those folks to work is a legitimate national security priority. For local public works departments, the only way to accomplish that task is private car transportation. Oddly, Bremerton produced an enlightened 2022 study, the JCTP, that contradicted the cars-only approach and favored a balanced transportation plan with multimodal and transit investments.

- Contractors – City of Bremerton streets projects often spend over 25% of total project cost on external contractors for planning and engineering. This reliance on contractors means Bremerton’s slender streets engineering team can’t build expertise to ensure projects work well for non-motorized transportation. Bremerton hires the same contractors again and again, like Parametrix and HDR, which are not well-regarded by the street safety community. Parametrix is currently working on no fewer than nine City projects, with a budget of no less than $1.9 million. An in-house civil engineering team would almost certainly cost less. And when going to bid, Bremerton should hire more progressive contractors, like Toole.

- Old ideas – Local public works departments are staffed by competent, hard-working people. But the senior leaders have been in their positions for a very long time. Bremerton’s Public Works Director and Chief Streets Engineer have both worked in the department for over 25 years. Kitsap County’s Public Works director and Director of Planning, 11 and 33 years respectively. Bremerton’s mayor is seeking his third term in 2025. These guys (and they’re all men) started building streets before protected bike lanes existed in Kitsap and, seemingly, they haven’t bought into modern safe streets concepts.

Solution: Building safe streets, not speedways

In Kitsap, pressure to change must come from citizens and elected officials. Grassroots groups like StreetSmart Bremerton are advocating for change, and both Bremerton City Council and Kitsap’s County Commission have majorities in favor of safer streets. A more forward-thinking Bremerton City Council has repeatedly overruled the more conservative Wheeler Administration, forcing the 12-foot multimodal path on Warren Avenue Bridge, forcing creation of Bremerton’s only protected bike lane and prohibiting parking in a bike lane.

Ultimately, Kitsap’s leaders need to decide what our streets and roads should be: should they be safe for people who live there? Or merely fast for people trying to get someplace else? For 75 years, Bremerton has chosen fast over safe. It’s time for a change.