The “no” recommendation from an editorial board that’s never supported a Seattle transportation levy carries very little weight.

In 2006, when Seattle Mayor Greg Nickels proposed a dedicated transportation levy to bolster the city’s street improvement fund, the new levy’s timeframe was initially set at a full two decades. The Nickels administration’s full funding package would have raised $1.8 billion over its lifetime, taking a sizable bite out of the city’s transportation maintenance backlog and allowing Seattle to invest in needed upgrades.

The 2006 vote came just five years after Tim Eyman’s I-747 had instituted a 1% property tax cap that was already starting to constrict city revenues — a problem that has only gotten worse over time. To overcome the cap, Nickel’s funding package augmented the property tax levy with a commercial parking tax and a $25 head tax on employers.

Nickels’ proposal met significant opposition, including from Eyman himself, who despite being a Mukilteo resident started to mount a full-throated opposition campaign. Less than a decade after voters had rejected a $90 million bond issue to repair city streets in 1997, the proposal was framed as a “forever tax.” The Seattle City Council folded and proposed a $360 million, nine-year levy instead. The council’s alternative raised 25% less per year than Nickels had proposed and covered a much shorter span.

However, that compromise measure was too aggressive for the Seattle Times Editorial Board, which recommended voters reject the ballot measure, anyway.

“The new, smaller version is better, but not by enough,” the board wrote days before the levy was on the ballot that November. “It is still laden with crosswalks, bike lanes, traffic circles, curb bulbs, stairways, road signs, tree planting, tree trimming and a renovation of King Street Station. We are in favor of most of these things, but many of them are, in the words of the Washington Policy Center’s critical report, ‘routine public work,'” they said, citing a conservative thinktank’s assessment of Seattle’s transportation funding situation.

Reading that editorial now, you’d be forgiven if you thought you were in the present day, reading the Seattle Times editorial board’s recommendation on the eight-year, $1.55 billion transportation levy before Seattle voters this November. In fact, the Times’ editorial board has never supported a transportation levy, insisting in 2006, 2015, and now in 2024 that while the city undoubtedly has immense transportation needs, this particular package isn’t the right way to make progress on them.

In contrast, The Urbanist elections committee (on which I’ve served since 2016) endorsed the Move Seattle Levy in 2015 and 2024’s Proposition 1. “[Prop 1] investments are critical, and without any transportation levy at all, the amount of funding available for new pedestrian and bike infrastructure in Seattle will plummet,” we wrote in our “yes” on Seattle Proposition 1 endorsement post earlier this month.

This year, the Seattle Times editorial board is taking a bold stance since the levy was crafted by a mayor and city council they overwhelmingly endorsed. Seven of nine councilmembers won the editorial board’s nod, most of them just last year. The Seattle City Council sent the levy proposal to voters in a unanimous vote earlier this year. But for all appearances it doesn’t seem to matter what the composition of city council is, nor who is mayor — the Times’ editorial board has never met a transportation levy it likes.

What’s the right way to fund Seattle’s titanic transportation needs? The board never comes out and says, instead dwelling on a fuzzy Goldilocks’ problem every vote. The board insists that the levy is both too big and too small to appeal to voters. This year’s Proposition 1 is no different.

This year, the board’s primary objection seems to be that the levy doesn’t go far enough in funding road and bridge maintenance, citing the fact that “only” $397 million — over 25% of the levy — would go toward arterial roadway repair. That amount is more than the entire 2006 levy, with another $221 million set to be spent on bridges. There the editorial gets its facts wrong, saying that the levy would spend just $127 million on bridge repairs, ignoring another $71 million in structural upgrades to Seattle’s movable bridges, as well as funds to advance bridge replacement projects into design so they’re eligible for federal grants.

The Times relies on the “expertise” of former transportation committee chair Alex Pedersen when it comes to bridge maintenance, who coincidentally represents the levy’s only substantive opposition and spent his four years on City Council trying to water down multimodal transportation projects.

When it comes to spending priorities, it sounds like the Times editorial board came to the same conclusion that many transportation advocates did early on — that a larger transportation levy is likely the only way to actually achieve many of the city’s goals around transportation. And yet an overall anti-tax attitude means they can’t bring themselves to support that.

At the end of the day, the main objection to Prop 1 voiced by the board is the levy’s $133 million category for protected bike lanes and bike lane upgrades, an amount that adds up to less than 10% of the levy. In 2015, the board was upset that spending on traffic signals was set at $13 million — now that Seattle is proposing to spend $100 million on traffic signals, the board is mad that bike spending is more.

Last year, in the face of record traffic fatalities on Washington’s roadways, the same editorial board called on the state legislature to take bold action. “Engineering of roadways, too, has a role to play,” they wrote last December. “Smarter street designs can help slow car speeds and increase the safety of bicyclists and pedestrians, whose death toll has tripled in the state over the last decade. Those are worthwhile improvements but they’ll take time when action is needed now.”

Now, they oppose those long-term investments in safe infrastructure, painting them as items to placate an interest group, rather than broadly popular investments that Seattleites both want and need to achieve broader city goals.

Ultimately, the board has exhausted its credibility in this area through its knee-jerk opposition in the past. In 2015, the board urged voters to reject the current $930 million Levy to Move Seattle, citing many of the same complaints.

“Move Seattle is a grab-bag of diffuse spending, buttering money around in seven-figure chunks that fit City Hall’s urbanist-at-all-costs agenda, not the lived experience of city residents,” they wrote. “The biggest investment, $250 million for maintenance and spot repair, barely puts a dent in the city’s nearly $2 billion maintenance backlog.”

Seattle voters by and large ignored that recommendation, with a 17-point margin of approval for that 2015 levy when all votes were counted, more than double the margin that Bridging the Gap received in 2006.

By most metrics, Move Seattle has been a success, even after facing numerous headwinds, such as a pandemic and federal grants drying up during the Trump administration. Those challenges prompted a course correction to adjust delivery targets downward when budget projections proved a bit too rosy. The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has been able to achieve a full 27 out of the 30 delivery categories promised to voters.

The ambitious targets that Move Seattle set also led to additional investments from other funding sources to shore up performance where things were coming in short, leading to additional projects than the city would have seen otherwise.

In short, the Move Seattle Levy has been instrumental to improving mobility in Seattle, covering 30% of SDOT’s budget. Without it, the city would be much worse off.

Proposition 1, dubbed the Keep Seattle Moving measure by supporters, builds on that legacy.

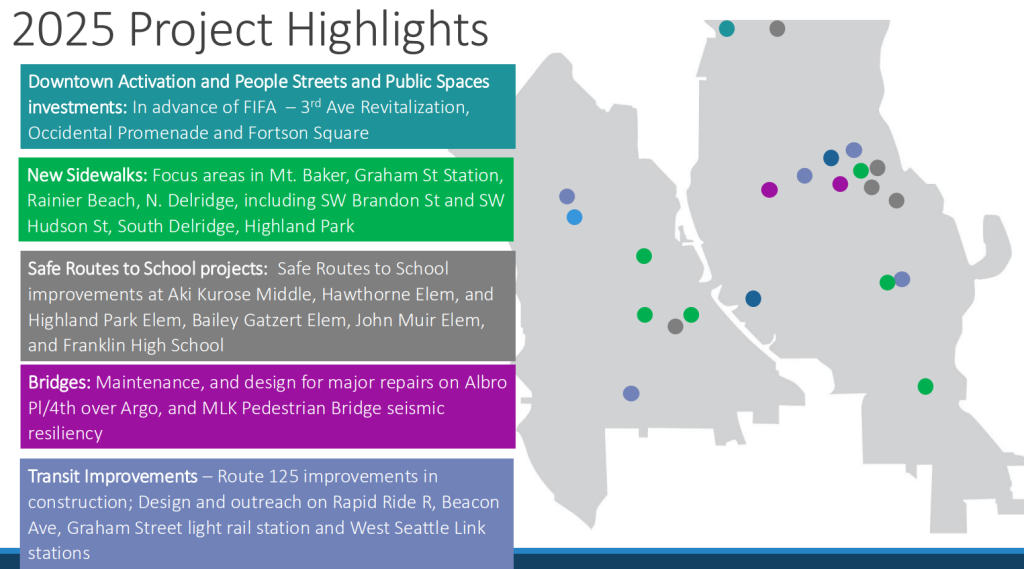

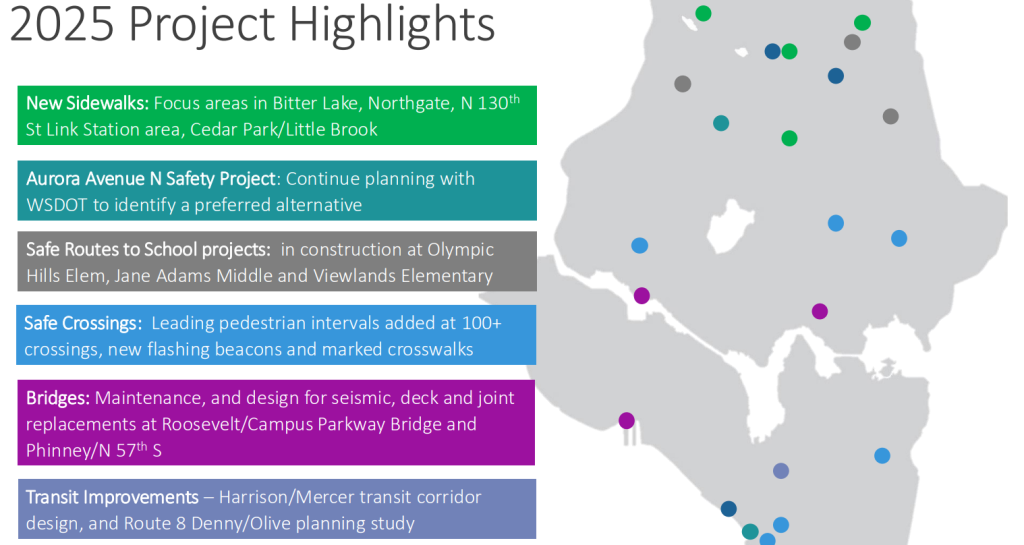

If Prop 1 is approved by voters, SDOT is set to immediately get to work to implement projects, with funding secured to be able to fill 71 positions that are currently vacant and another 116 positions in the next two years. 40% of those new hires will support pedestrian safety and Vision Zero projects, according to a presentation the department shared with the city council last week. Planned 2025 projects include upgrades across the entire city, including work to hit the ambitious goal of building 250 blocks of new sidewalks in five years.

If Prop 1 is not approved, funding for arterial repaving will drop by 52%, SDOT will have to eliminate an entire shift from its traffic operations center, and funding for bike infrastructure would drop by 75%. That’s probably fine with the Times editorial board, but it will mean worse mobility for Seattleites.

If the Times succeeds in blocking the levy this year, the City’s second attempt to renew it is very likely to be slimmer and include less infrastructure that a growing city needs in the 21st Century. Failure at this year’s ballot box isn’t likely to prompt bolder thinking, especially from this current mayor and council, who will still be holding the reins next year.

When filling out their ballots, voters should keep in mind that if the Seattle Times editorial board had been listened to, Seattle would be even further behind than it is now.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.