Yesterday, the Sound Transit Board of Directors approved the route for West Seattle Link in a 14-2 vote, clearing the way for engineering work that will advance the project to 80% design by 2027. The two boardmembers who opposed the motion — Pierce County Executive Bruce Dammeier and Puyallup Mayor Jim Kastama — raised concerns that rising costs for Seattle expansions would jeopardize plans to extend light rail to Tacoma and to Everett.

“Fundamentally this is a project that has seen dramatic cost escalation — it has gone from $4 billion to over $7 billion. And all our programmatic work that our capital team is going to do not going to pull $2 billion out of this project,” Dammeier said ahead of the vote. “It’s going to still be dramatically over anything we’ve envisioned and anything the system budget can handle in mind.”

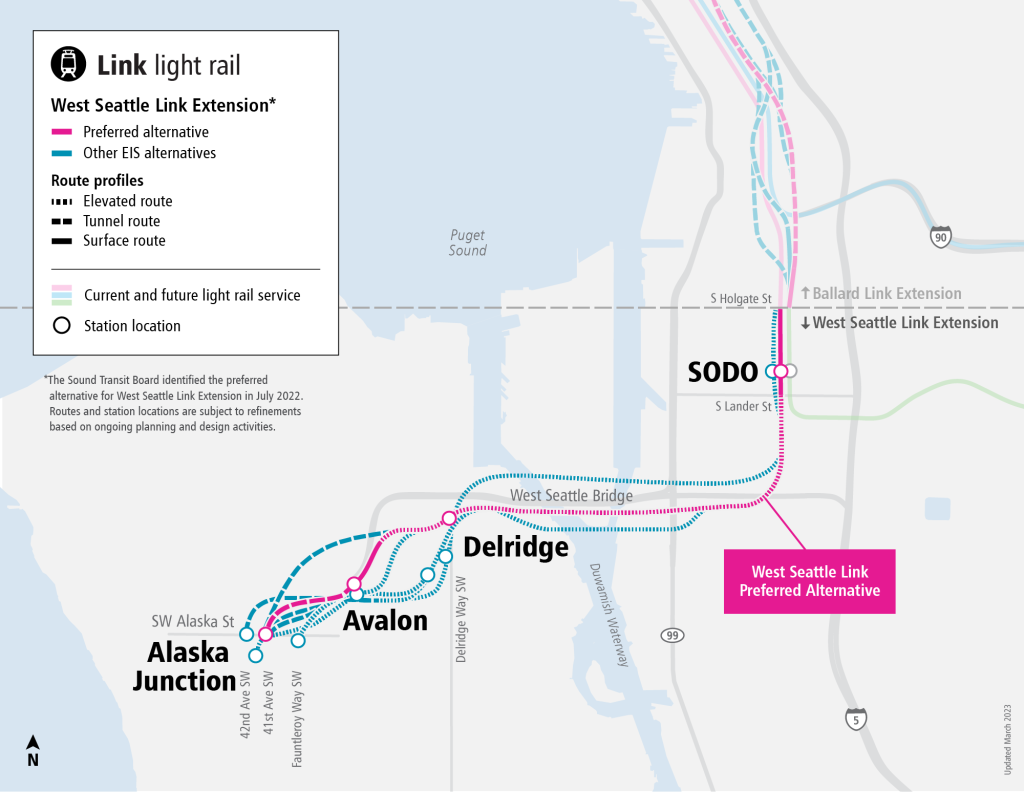

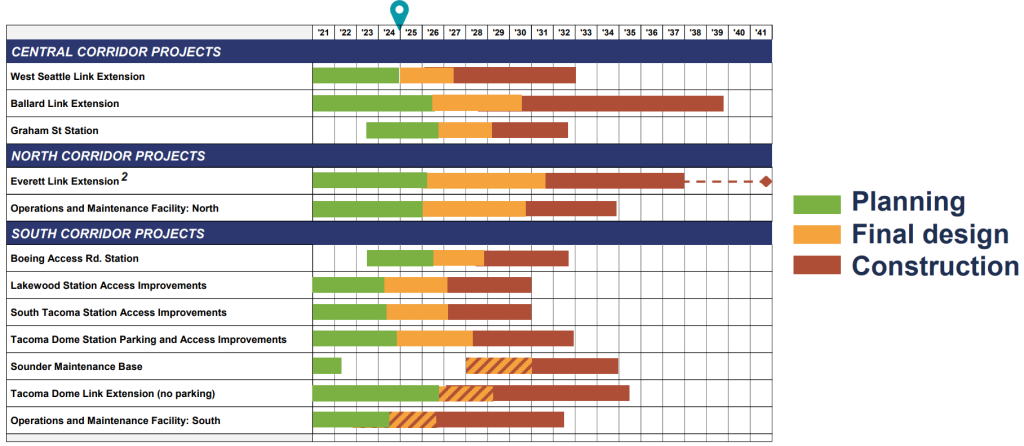

However, a majority of board members were swayed by the agency’s recommendation to approve the route as the “project to be built” so that they could keep the 4.1-mile line advancing and look for savings as they refine the design, as promised in committee last month. The agency hopes to complete West Seattle Link in 2032, but cost overruns could jeopardize that schedule.

In September, Sound Transit revealed the extent of cost issues on West Seattle Link. Days after the release of the Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) megastudy showed $1.1 to $1.6 billion in increased costs for the board’s preferred route, the agency has admitted that overrun was simply the tip of the iceberg. Sound Transit’s more recent and thorough estimates, first shared with the Seattle Times, put the projected overrun at $2.7 to $3.1 billion, or between 67% and 77% higher than the $4 billion estimate in the Draft EIS.

Several members, including Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) secretary Roger Millar, noted that cost escalation has been a national issue across infrastructure projects, tied to inflation and macroeconomic conditions.

“We are talking a lot about sticker shock with this project,” Millar said Thursday. “In my experience, the program I run during my day job, we’re seeing the same kind of sticker shock. It’s not unique to this corridor. It’s not unique to Sound Transit. It’s not unique to Washington state. That’s what we’re seeing nationwide and indeed worldwide at this point in time. So I think the systemwide analysis we’re doing will serve us well in reducing costs in this environment of rapid cost escalation.”

However, West Seattle Link’s cost increases also appeared to have been exacerbated by routing decisions (particularly a costly tunnel alignment in Alaska Junction) and a slow-moving process to establish a preferred alternative.

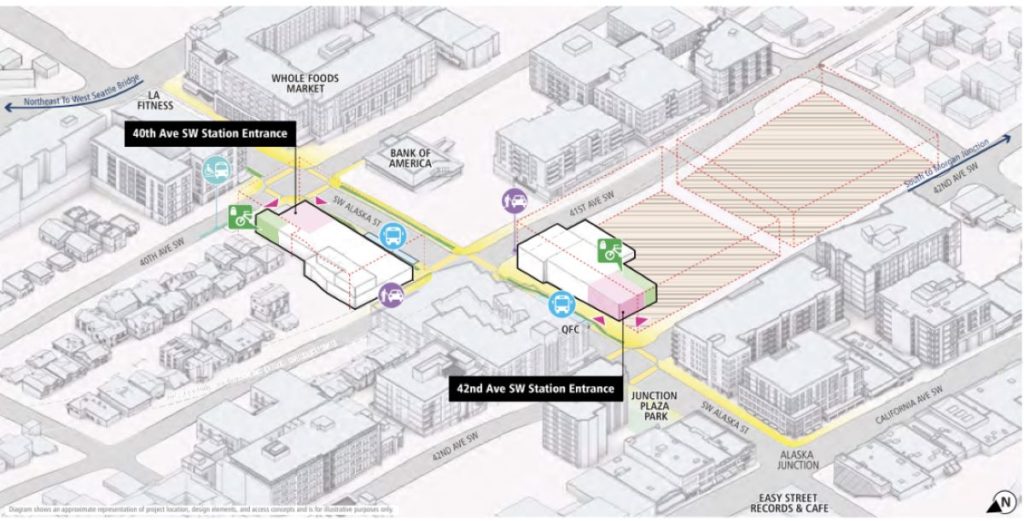

The agency’s default “representative project” initially included an elevated station along Fauntleroy Way. In fact, Sound Transit staff had told the board that switching to a tunnel station would require “third-party funding” arranged by the City of Seattle, acknowledging the higher expected costs for tunneling. However, facing pressure from the board, the agency relented on requiring third party funding, helped by the fact that the Draft EIS cost estimates showed the elevated Fauntleroy station only slightly cheaper than the tunnel station the board selected.

Those Draft EIS estimates now appear a mirage in light of the Final EIS, which showed a $600 million to $850 million gulf between the new tunnel alignment and the cheaper Elevated Fauntleroy option. Nonetheless, the suspect DEIS cost estimates cleared the way for the board to catapult the 41st Avenue tunnel option into preferred alignment status.

The public comment period before the board’s vote was mixed, with some pushing the board to forge ahead with their current plans and others encouraging them to weigh alternatives. One contingent suggested the board nix the light rail station planned in Avalon to curb costs.

Nathan Rose, a West Seattle resident who lives near the planned line, expressed surprise at the lack of discussion of the alternative alignments that are still officially in the study, but that, in contrast to the preferred alignment, are not getting detailed engineering work.

“All I’m asking you today is just take the time to discuss the alternatives before you,” Rose said. “Don’t just rubber stamp the status quo, but actually consider the pros and cons of each. Two weeks ago in the System Expansion committee meeting, multiple committee members brought up concerns about the power lines in SoDo, but none of them mentioned the alternatives in West Seattle. Literally zero mentions of alternatives in West Seattle. In committee and board meetings last year, there was never any discussion other than just a vote yes.”

Rose alluded to the Elevated Fauntleroy alternative that the agency’s FEIS projected would cost $600 million to $850 million less than the preferred alternative of a tunnel alignment under 41st Avenue. The board’s decision to pursue a tunnel station in Alaska Junction was partly based on neighborhood pushback that raised aesthetics concerns with an elevated rail line in their midst.

Meanwhile, the Ballard Link alignment through Downtown has run into numerous snags as well, with several parties raising concerns about construction impacts. Some activists in the Chinatown-International District (CID or ID, for short) also flagged displacement concerns and asked Sound Transit to site the station outside their neighborhood.

Ultimately, the board heeded that call and proposed entirely new North and South of CID alternative in 2023, forcing the agency to re-do its Draft EIS for the Ballard Link. To keep Ballard Link changes from holding up West Seattle Link, Sound Transit separated the previously joined Seattle projects into two separate proposals before the Federal Transit Administration. That decision has delayed Ballard Link, putting it on a planning timeline that is tracking three years behind West Seattle Link.

Construction will also take longer for the more complicated Ballard Link project. The agency has said the best case scenario is to open Ballard Link in 2039, though cost escalations threaten even that timeline, which is four years later than the Sound Transit 3 ballot measure pledged to voters in 2016. Under Ballard Link opens, West Seattle Link will operate as a stub line, with transfers to the 1 Line in SoDo.

“It feels like because the routes in Ballard and the ID are so contentious that the board wants to take it easy in West Seattle,” Rose said. “The decision that you make today will displace hundreds of residents and businesses and affect thousands more. Given the difference between the alternatives amounts to hundreds of millions of dollars, this actually affects every single taxpayer in the Puget Sound area. Your constituents deserve more than to be brushed off in the name of expedience, this decision deserves deep analysis and careful comparison. So, please do the right thing today, and discuss the alternatives before you so that you can make an educated decision.”

Dammeier also pushed back on the idea that the board could sort out the tradeoffs at a later date.

“That design is going to create expectations of what we’re going to do, and I don’t know how the system is going to deliver on those expectations,” Dammeier said. “Beyond this project, I’m concerned we’re going to have a similar discussion about the Ballard Link Extension. When you add those things together… I am very concerned that that this jeopardizes the system’s ability to get to the spine.”

Skepticism of rising costs on Seattle lines was strongest from the board contingent from Snohomish and Pierce counties. While only Dammeier and Kastama voted no, several other non-King County members expressed reservations about rising costs and made it clear “completing the spine” from Everett to Tacoma was their top priority, including Lynnwood Mayor Christine Frizzell and Everett Mayor Cassie Franklin.

The 18-member board is weighted by population — only the county population that falls within the Sound Transit Taxing District counts. Snohomish County has three members, Pierce County has four, King County has 10, and the WSDOT secretary gets the 18th seat. County executives are automatically on the board, and they are also tasked with making appointments for their delegation, though appointees must be an elected official to be eligible.

Franklin pressed agency leaders on when the next major decision point will be for the board and asked whether they’d have sufficient time to thoroughly weigh options once they have more information. Deputy CEO for Megaprojects Terri Mestas said that the agency is likely to ask the board to approve construction awards shortly after reaching 80% design gate, when they would baseline project costs.

“It’s likely to be early- to mid-2027 when we come back to the board to consider baselining the project,” Mestas said.

That’s likely to be the last turning back point. However, by 2027, any major changes to the design could upend the project and mean major delays, which incur costs in their own right due to inflation and added engineering costs.

Kastama zeroed in on the sentiment that King County was hoarding all the resources. He flagged the Gateway project, which has been long-planned to supercharge SR 509 and SR 167 freeways near the Port of Tacoma, but has been delayed for decades as costs ballooned.

“I dealt with it in highway expansion,” Kastama said. “For example, we’ve had the Gateway project for 30 years that has yet to be built in Pierce County, bringing 100,000 jobs. And yet — whether it be the 520 bridge or Alaska[n] Way Viaduct — there was always something that comes up that says these other projects are more crucial than this one that’s been outstanding for 30 years.”

Taking the argument a step further, Kastama argued King County siphons resources away from other counties.

“It’s a tenor of elected officials here of great skepticism when we start moving on and we start diverting resources to other projects, especially in King County,” Kastama said. “They seem to get precedence over the long run when it comes to actually make these decisions.”

It’s very likely Tacoma Dome Link Extension and Everett Link Extension will have cost escalation issues of their own to contend with, which may help balance out the distribution of resources between subareas. However, cost escalation across the board would certainly be bad for riders hoping to see the transit they were promised open sooner.

Whether Sound Transit has a viable plan to address rising costs without further delaying projects is a question for another day. The train to West Seattle has left the station, and it’s headed underground.

Doug Trumm is publisher of The Urbanist. An Urbanist writer since 2015, he dreams of pedestrian streets, bus lanes, and a mass-timber building spree to end our housing crisis. He graduated from the Evans School of Public Policy and Governance at the University of Washington in 2019. He lives in Seattle's Fremont neighborhood and loves to explore the city by foot and by bike.