Bellevue, Seattle, and Tacoma are each working to expand tree protections, and all should go further to expand canopy.

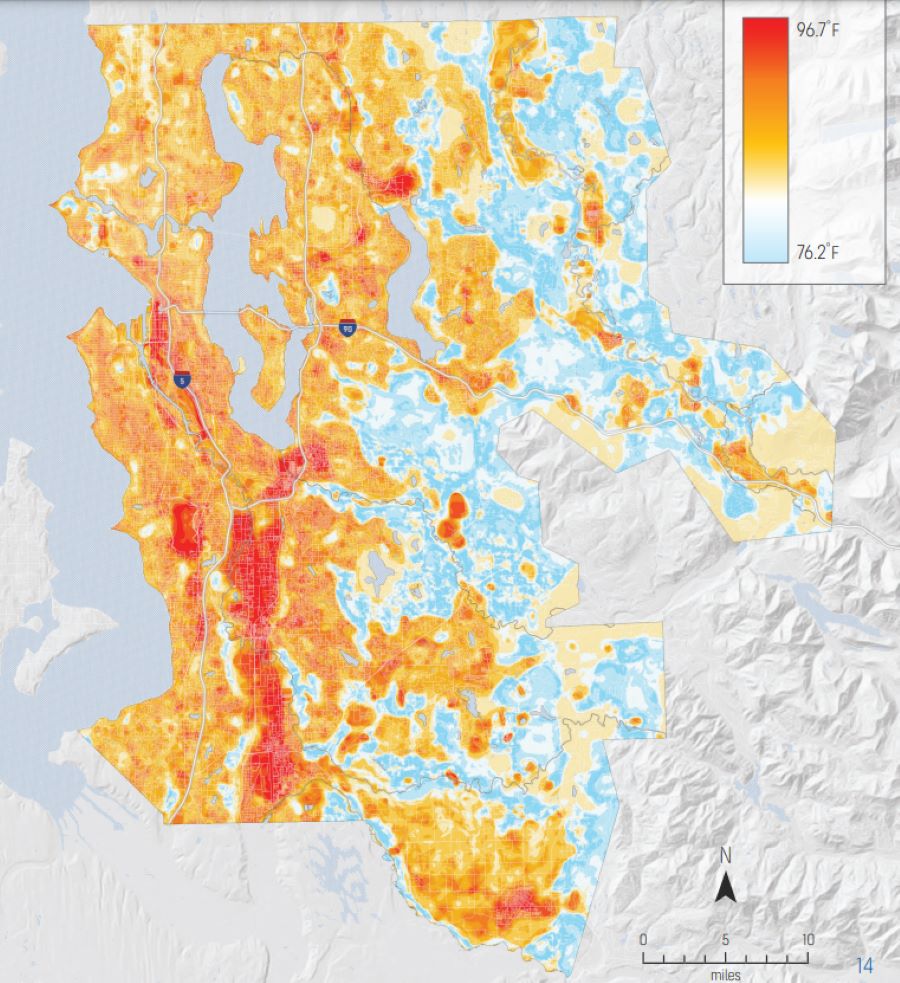

The summer of 2024 was the hottest year on record, and cities have been increasingly forced to grapple with the impacts of climate change at the local level, including helping residents cope with heat waves.

Several Puget Sound cities have embarked on efforts to expand tree canopy. Bellevue recently joined their ranks, taking it upon itself to address the shortage of trees in some of its neighborhoods and limiting exploitative development practices citywide.

In July, Bellevue amended several sections of its tree code, seeking to preserve more trees and encourage more plantings with new development. Bellevue is not the only major city in Washington to take a second look at their tree regulations. Seattle and Tacoma, two of the other largest cities in the Puget Sound region, recently amended their codes as they continue to tackle issues of housing affordability, urban livability, and the local effects from climate change.

Trees are unique in that they are both a climate adaptation and a climate mitigation. Expanding urban tree cover adapts to climate change by moderating heat waves and helping to absorb stormwater in increasingly common major storm events, making cities more livable in a warming climate. Reforestation can also mitigate climate change by sucking carbon (the primary climate pollutant) out of the air and locking it into trees, while decreasing the heat absorbing quality of urban environments in the process.

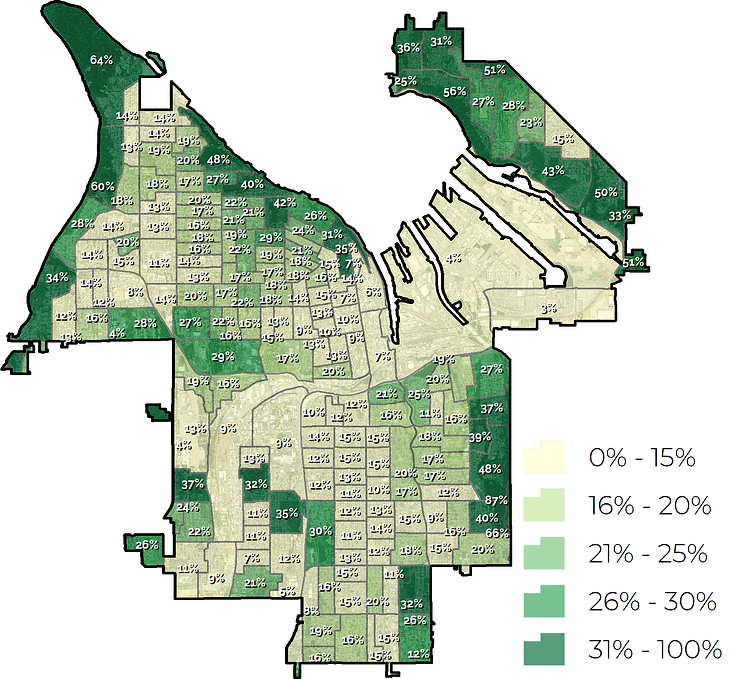

Despite promises of maintaining what makes the Emerald City green, Seattle has seen a decline in its tree canopy from 2016 to 2021 (dropping from 28.6% to 28.1%). This is below the 30% tree canopy goal the City Council adopted in 2013 under their Urban Forest Stewardship Plan (UFSP). Compared to other nearby cities, Seattle’s tree canopy has deteriorated over the years compared to the 38% tree canopy of Redmond, and the 40% of Bellevue.

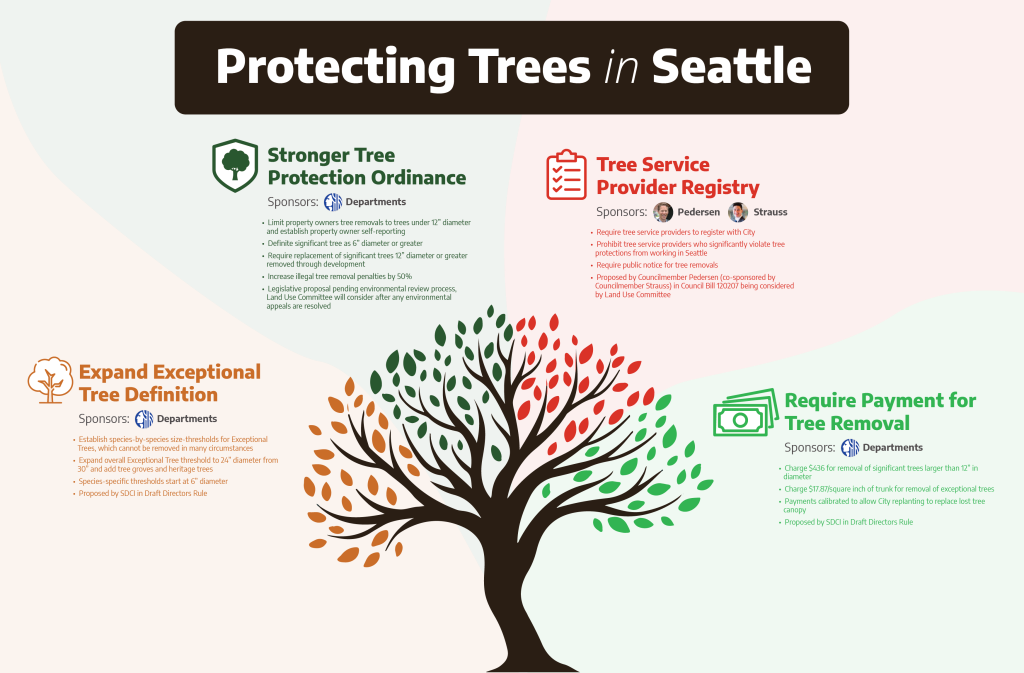

Seattle’s reformed tree canopy ordinance strengthened the code to protect urban greenery by expanding regulatory protections, making it more difficult to remove trees with a diameter of 24 inches or wider. If a tree over one foot in diameter is removed, the city requires a replacement of one or more trees that will eventually grow to have comparable canopy coverage – something developers would need to foot the bill on.

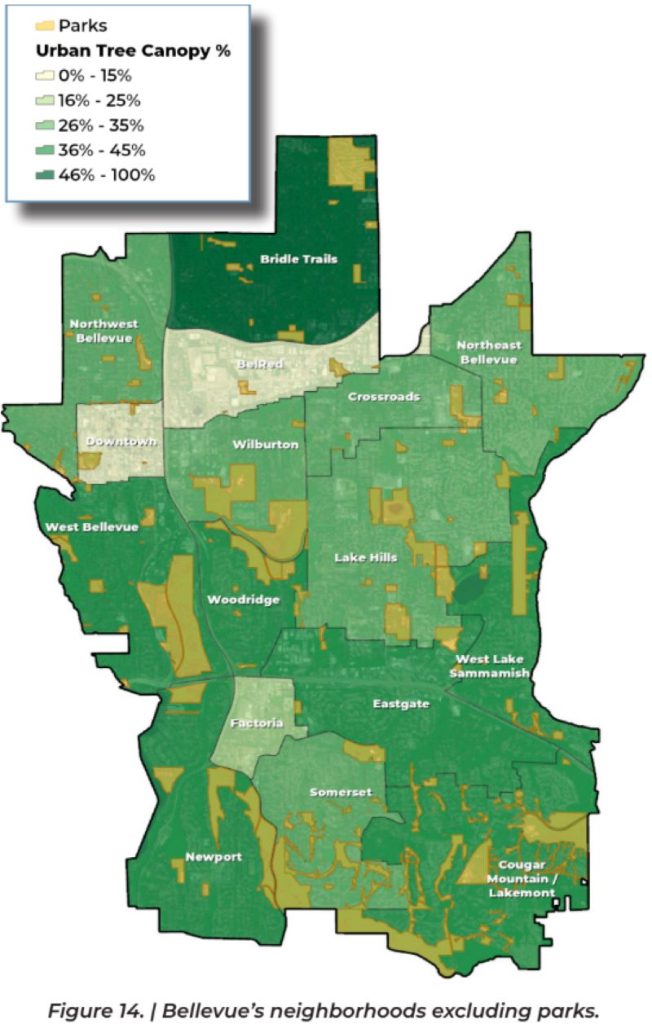

Bellevue’s recent tree code changes are a bit more strenuous, designed to maintain the 40% tree canopy coverage measured in 2021. Under the new changes, permits are now required to remove significant or landmark trees, and development proposals must attain a minimum tree density factor, allowing options for tree replacement.

Insofar as maintaining current levels of tree cover in Puget Sound cities, these measures appear poised to achieve those goals. However, in trying to dramatically expand tree canopy, the amendments fall short.

With their focus on low-density residential neighborhoods, Bellevue’s amended ordinances would not address the relative lack of tree canopy in downtown, putting barren areas like this especially at risk during hotter summers, as heat maps show. Even in neighborhoods where they apply, the ordinances rely on new development projects and separate incentive programs during redevelopment to spur tree planting.

Still, the tree canopy density requirements are a great model for other growing and developing cities in the Puget Sound, Bellevue enjoys a higher-than-average tree canopy that other cities lack.

Take for example, Tacoma. The City of Destiny suffers from higher heat from its lack of tree canopy, especially in neighborhoods south of I-5. Only 20% of the City’s land area is covered by tree canopy, the least of all communities assessed in Western Washington. In the underserved areas of South Tacoma, South End, and Eastside, few make it above 20% tree coverage per land area.

Downtown Tacoma is lucky to make it above 10%. The heat maps and tree data underscore issues regarding racial equity and the legacy of historic marginalization and institutional racism.

Trees are certainly an equity issue – historically marginalized communities suffer from a lack of infrastructure investment and impermeable surfaces. Trees are natural air conditioners, having a significant cooling effect that reduces temperatures in our urban settings. The scarcity of trees in low-income neighborhoods is why the urban heat island effect is worse in those areas.

Tacoma has set a goal of reaching 30% tree canopy by 2030, but has made slow progress. The ordinance the Tacoma City Council adopted in December 2023 funds urban forestry programs through fees on tree removals, protects large trees designated as significant or historic, and allows the planting of fruit trees in the public right-of-way.

Metro Parks seeks to develop an Urban Forest Management Plan and fund more tree planting in public parks with grants from the Department of Natural Resources. With gaps still present, Tacoma has taken steps to address its inequitable and sparse tree canopy.

While cities like Tacoma would need to adopt similar ordinances like Bellevue’s to maintain what they have, they leave something to be desired in taking an active role in growing cities’ tree canopies. Cities like Tacoma with direly sparse tree cover need to take a more active role in growing their canopy.

Tacoma should incentivize and even consider requiring that landlords increase tree canopy over time, both through new building projects and upkeep of their properties. When it comes to reducing the urban heat island effect, replacing paved surfaces with trees would have a doubly beneficial effect. The city could partner with organizations for reforesting privately owned lands.

Doing so would not only reduce heat-related health issues in the summers and grant cooler temperatures in historically marginalized communities, but would also prepare for the worst effects of future hotter summers. However, the root problem of climate change still needs to be directly addressed, and that stretches beyond local authority.

While Bellevue’s local changes are positive, the need for bolder policy at the state, federal, and international levels are the only ways to tackle the fundamental underlying problem: climate change. As climate change continues to be tackled at an international level, cities need to focus their attention on local tree canopies to make cities in the Pacific Northwest and elsewhere more livable.

Collin Thrower

Collin Rhys Thrower has long had an interest in policy issues that affect lives – whether it is healthcare, welfare, civil rights, or democracy itself. He sees politics as a puzzle, trying to solve systemic problems that have the chance to either do great good in the world or enact great harm. Born and raised in San José, California, Collin has a thirst for knowledge, learning, and growing in new spaces. Residing in Tacoma, Collin has a Master's in Political Science from Northeastern University.