The relative lack of apartment zoning in Mayor Harrell’s growth plan is drawing criticism from housing advocates.

Mayor Bruce Harrell has released a final draft of the growth plan he’s proposing as part of the major update of the city’s Comprehensive Plan, set to be considered by the Seattle City Council in early 2025. Despite some substantive changes to the version released earlier this year, the zoning framework remains largely the same. The dearth of new zoning for apartments is already drawing criticism from some housing advocates.

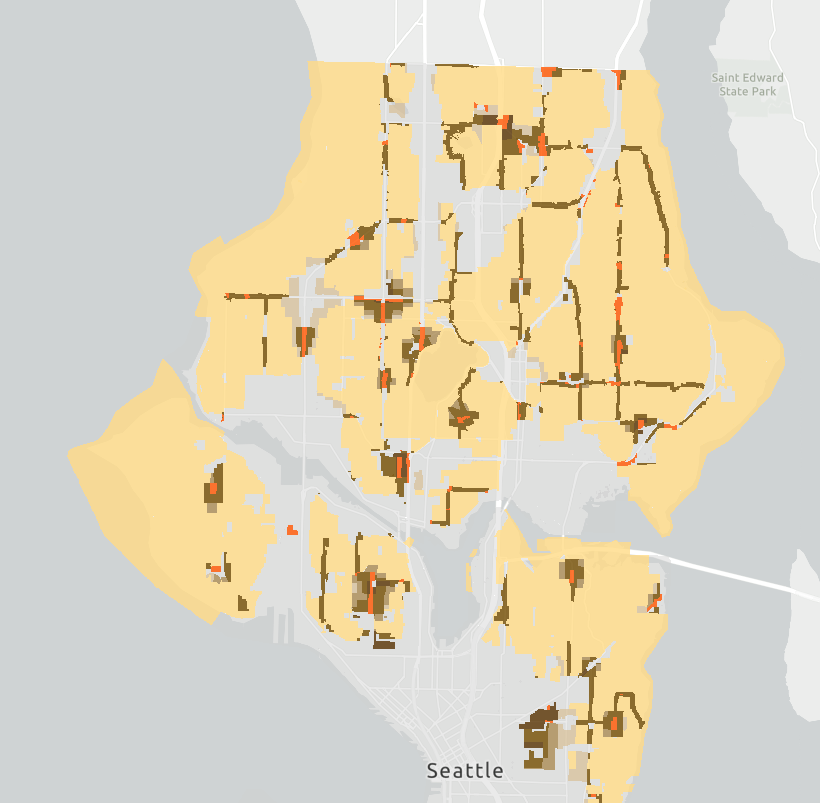

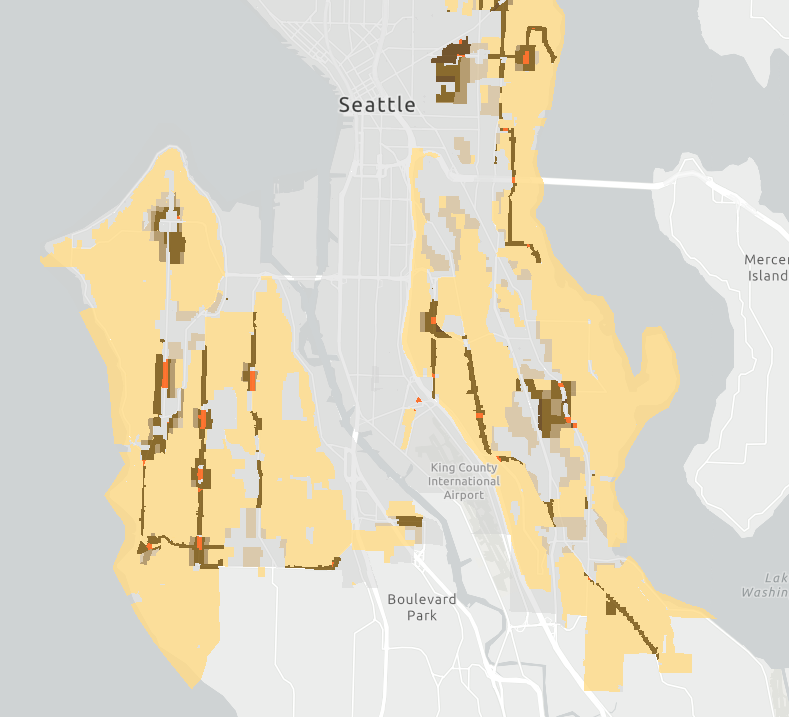

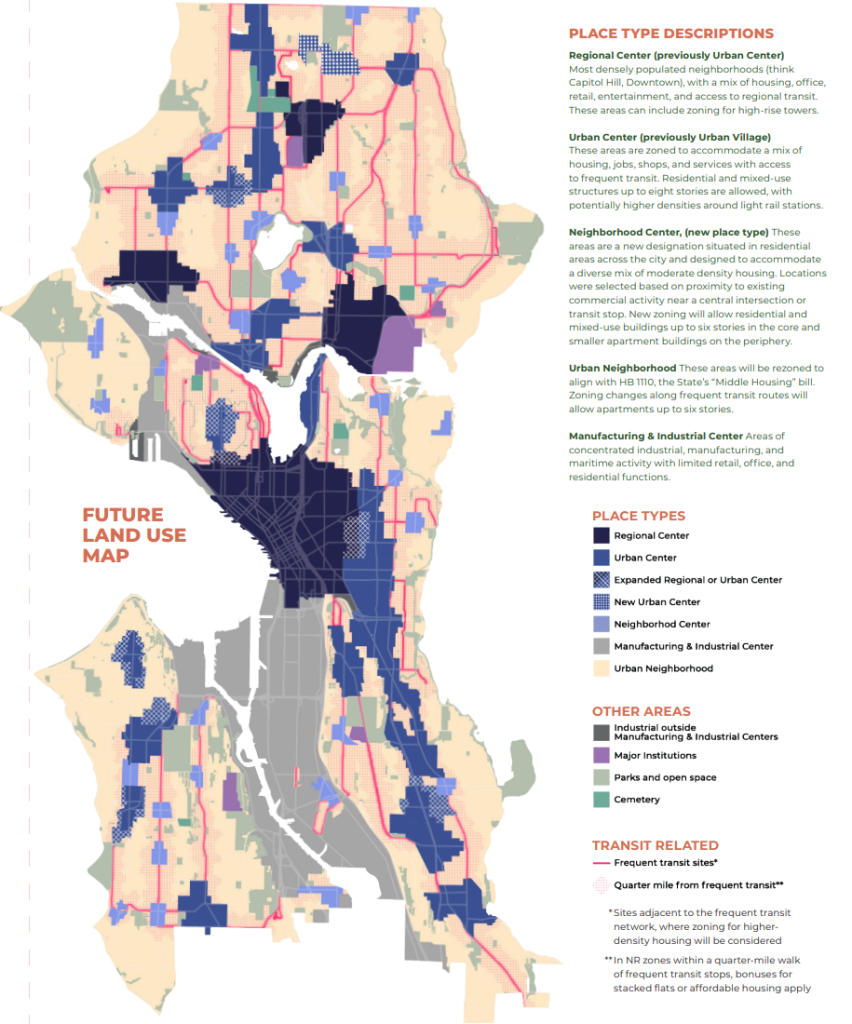

Under Harrell’s plan, the majority of the city’s planned growth would be confined to similar areas along major arterial streets, while single-family zones — even those near high-value amenities like schools, parks, or frequent transit — would be walled off from apartment construction and integration with the rest of the city. While fourplex zoning replacing single-family zoning is likely to draw the most attention, the vast majority of Seattle’s growth (85% or more) over past few decades has been multifamily housing in the limited areas designated urban centers and villages, and that will likely continue to be the case.

The initial version of the plan, released in March, was criticized by a broad array of groups including the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce, state legislators, the city’s own planning commission, and even some of Harrell’s most ardent supporters like Councilmember Tanya Woo. Despite the consensus that the plan didn’t go far enough, the administration didn’t go back to the drawing board. They hewed to the same framework, while allowing marginally more housing options.

The materials released Wednesday include both tweaks to the plan’s initial draft, including the addition of five new clustered growth centers at existing commercial hubs dubbed “neighborhood centers,” and updates to regulations increasing the viability of multiplexes in the city’s formerly single-family zones. The mayor has removed the fourplex zoning exemption for high-displacement risk areas he proposed in March and eased limits on the size of buildings in fourplex zones, making construction more viable and likely to happen.

Also included in Wednesday’s release are the plan’s first detailed zoning maps revealed to date, filling in actual boundaries that had previously been fuzzy and ill-defined. A public comment period is open through December 20 with an online comment portal and a series of open houses.

City officials are touting the expanded housing capacity created by the proposed changes, increasing the total amount of potential new housing citywide to 330,000 units, though the number that’s actually expected to be produced over the next 20 years will remain well below that. Because the March version of the plan was not fully fleshed-out with zoning or boundaries, quantifying the change in capacity over the earlier draft is tricky, but previously a capacity number in excess of 200,000 units had been touted as the new baseline.

Since the City has estimated existing zoning (before any updates stemming from the Comprehensive Plan) already had capacity to add 167,000 net new homes, advocates had argued the March draft fell short and did not encourage housing abundance that could ease the housing affordability crisis.

Creating “more than 30” neighborhood centers

The March draft proposed 24 new “neighborhood centers” — areas of concentrated growth primarily located at existing commercial centers like Montlake, Tangletown, or Dravus Street in Interbay. Intended to be a smaller version of an “urban village,” the idea has long existed in Seattle planning under the former moniker “neighborhood anchors.” The new plan adds just five more — in North Magnolia, High Point, Central Beacon Hill, North Fremont, and Hillman City.

The Complete Communities Coalition, which includes the chamber, House Our Neighbors, The Urbanist, and many more groups, had asked the mayor to double the number of neighborhood centers, adding back all those studied in the environmental review — not add only five. These areas would be likely to host apartments, with height limits around six stories near their cores.

Under the mayor’s plan, a new urban center (the new name for urban villages) would be created near the coming N 130th Street light rail station, and the existing South Park urban village would revert to a neighborhood center, a designation that more accurately reflects its existing zoning.

By expanding both the First Hill/Capitol Hill regional center and the Central District urban center, filling in a longstanding “donut hole” on the city’s zoning map, the city is actually taking credit for adding more than 30 new neighborhood centers, but that does represent a step back from the 46 potential neighborhood centers that the city studied in its environmental review.

As The Urbanist reported earlier this year, planners at the Office of Planning and Community Development (OPCD) had proposed a total of 50 neighborhood centers in an early draft of the plan, one that was significantly scaled back by higher-ups in the Mayor’s Office. Those mayoral revisions also greatly delayed public release of the growth plan, which had once been promised almost a full year earlier.

Traffic-oriented development

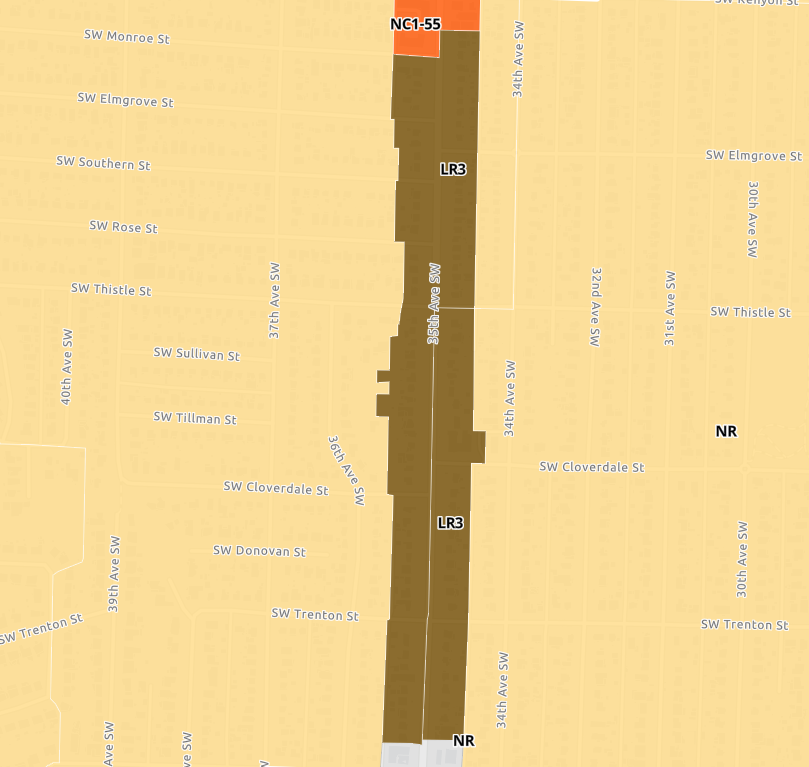

Apart from the new neighborhood centers, the primary areas that will see upzones will be dozens of streets with frequent transit service — not areas off arterial streets close to transit stops, but directly along the arterials, which tend to be some of the highest-traffic corridors in the city. In the end, this growth pattern serves to “buffer” residents of lower-density areas from their busy neighborhood street and ensures that renters, who generally live in higher density housing than homeowners, are more directly impacted by noise and pollution.

In its letter on the initial draft of zoning changes, the Seattle Planning Commission — appointed by the mayor and city council to weigh in on issues just like these — directly called out this issue.

“The current housing market locks the most affordable homes, multifamily apartment buildings, into small areas of the city that are often along noisy and polluting major highway corridors or in areas that historically faced disinvestment,” they wrote. “If the City continues to concentrate affordable housing types like multifamily apartments in the same areas of the city, these long-term patterns of inequity will not change. The City should plan for more multifamily housing in more areas of the city such as in high access to opportunity areas and near amenities like large parks, schools, and healthy food sources.”

At a press briefing on the plan Wednesday, Michael Hubner, the City’s Long Range Planning Manager, defended the idea of zoning along corridors instead of proximity to transit stops by stating that most bus lines in the city have consistent stop spacing and that King County Metro could end up moving stops in the future.

“There may be some exceptions to that where it’s a little bit further, every transit line is a little bit different, but we felt pretty comfortable that zoning for more housing along the arterials does provide a reasonable level of accessibility to transit that’s on the arterial,” Hubner said.

Ultimately, keeping the densest housing confined to the arterial streets will continue to put significant redevelopment pressure on the city’s commercial spaces, which are predominantly located on the same arterials, and only serves to ensure that the vast majority of the city’s lower-density areas don’t have to see as much development. Restricting apartments to arterials goes directly against the advice given by housing advocates, including the Complete Communities Coalition.

“Allow midrise and mixed-use housing within a five-minute walk of frequent buses,” the coalition wrote in their letter to the mayor. “Building homes near transit gives people more choices in how they get around their neighborhoods and makes transit a convenient option for more people. And building those homes off arterials but still near transit gives people the opportunity to live in quiet, low-pollution, and car-light neighborhoods.”

The silver lining: Missing middle

The biggest change in the plan toward more density compared to what was released in March is in the “urban neighborhood” zones — formerly single-family zones that are affected by House Bill 1110, which the state legislature passed in 2023 to require a new level of minimum required density everywhere.

Initially, the Harrell Administration proposed to do the absolute bare minimum when it comes to urban neighborhood zones. All new development — including duplexes, triplexes, and fourplexes — would have been forced to adhere to a requirement that kept the amount of floor area in a new building the same as it would have been if it were a single-family home being proposed. This would have forced each fourplex unit to be smaller, decreasing their financial viability for builders.

“The proposed changes […] are not likely to change what can reasonably be built in those areas nor make it possible for low-income households to live in these neighborhoods,” the planning commission noted at the time.

Recently, the King County Affordable Housing Committee joined in on the criticism of this policy, as The Urbanist reported.

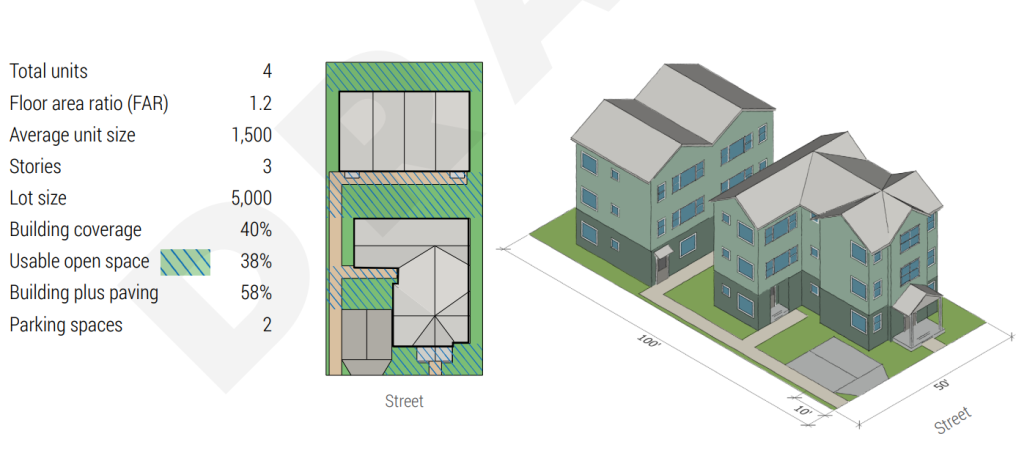

The draft legislation released this week would increase the amount of space that middle housing, including duplexes, are allowed to take up on a lot by 33%, increasing the floor area ratio (FAR) — the amount of space that the floor area of a building takes up compared to the total size of a lot — from 0.9 to 1.2. This will make denser projects much more feasible and allow comfortably family-sized homes.

On top of that, on larger lots in areas within a quarter-mile of frequent transit or half-mile of a rail station, builders can go even further, achieving 1.4 FAR if they’re stacking the units, an incentive for developers to create stacked flats over townhomes. Utilizing that provision would mean that builders could construct nine units on a 6,000 square foot lot, a lot that is a little larger than an average Seattle residential lot.

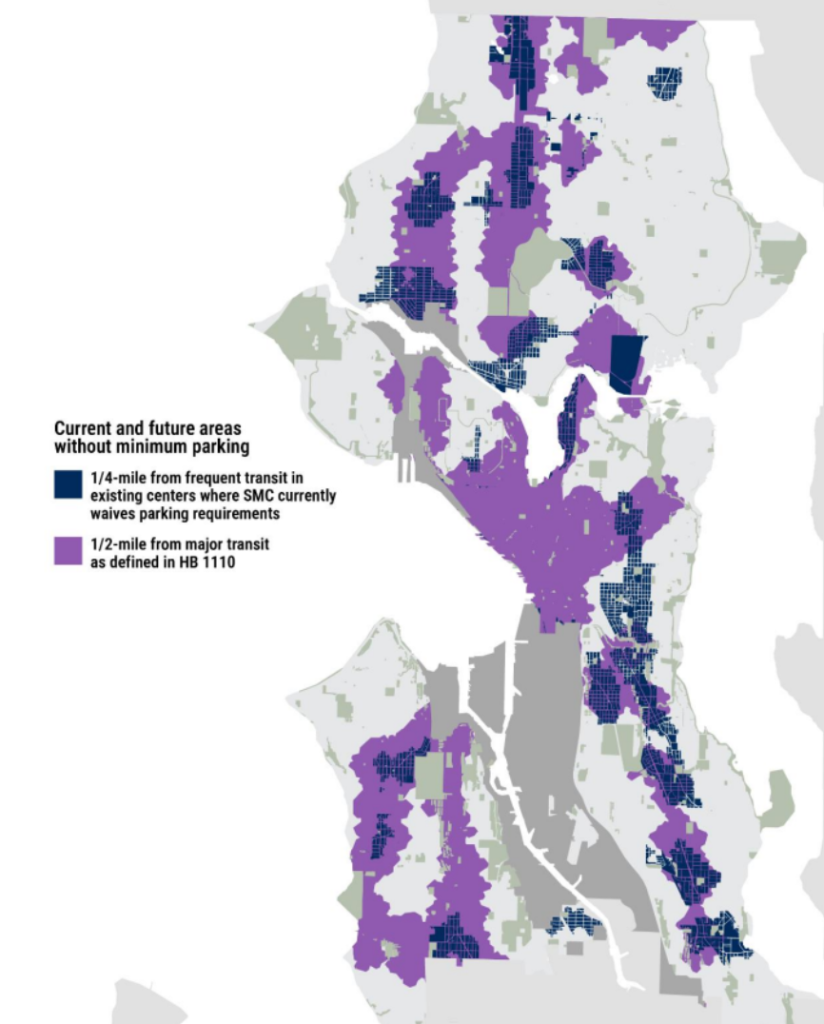

Parking mandates staying in place, but being reduced

Increasingly, cities across the country, large and small, have entirely ditched parking mandates, which force homebuilders to construct a minimum number of parking spaces. Despite being a national leader on eliminating mandated parking near transit in the past, Seattle is set to take a more incremental approach. With HB 1110 requiring Seattle to exempt areas within a half-mile of major transit stops, the Harrell Administration proposes to keep them in place in areas away from RapidRide and light rail stops. Instead they’ll drop down to one stall for every two units, so building a duplex would only require one stall and a fourplex two.

Accessory dwelling units (ADUs) would continue to be exempt from parking mandates, as they are now — but also soon to be a statewide standard.

The proposed legislation around parking minimums would also erase existing “parking overlay” districts that require developers to go above-and-beyond existing minimums in areas like Alki and around the University of Washington, a positive step toward removing mandated parking everywhere.

The plan heads to City Council in 2025

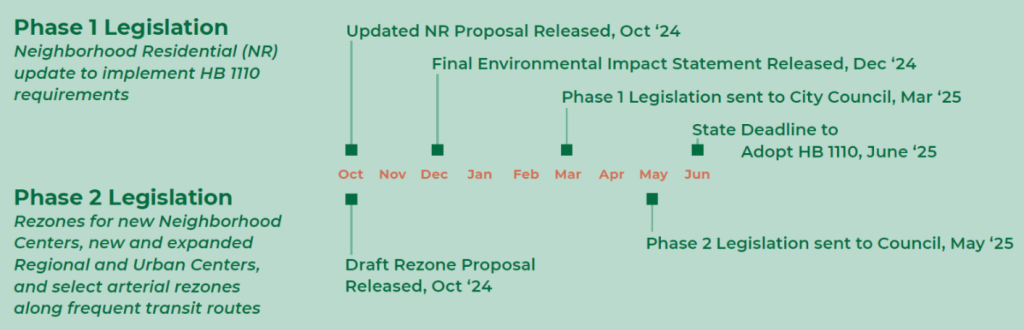

What happens next? In December, the City will be releasing the final environmental impact statement (FEIS) for its selected growth alternative, with legislation for the zoning changes in neighborhood residential zones set to be sent to the City Council by March, with the aim of meeting the state deadline for compliance with HB 1110 in July. If the City of Seattle fails to meet that deadline, the state’s model middle housing code would temporarily go into effect, superseding single family zoning until such time as Seattle enacts compliant zoning.

Next May, OPCD plans to send the neighborhood center legislation to Council, a few months later than the neighborhood zoning changes. Technically, the Comprehensive Plan update was due at the end of the 2024, but the Growth Management Act (unlike HB 1110) is light on enforcement mechanisms, particularly for lateness.

The City Council will have the ability to modify the plan, but extent of those changes will be guided by what environmental review the city has already completed. Given the limited changes the plan has seen between March and now, the additional opportunities for housing density will likely be enough to placate some of the councilmembers who were calling for the plan to go further, but there could also be some surprises.

Make your voice heard: Comment via the online comment portal or the City’s open house series through December 20.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.