As a new 45-story apartment tower goes up along Denny Way, Seattle is building apartments at a rapid pace – but a slump may be on the way.

In mid-August, developer Holland Partner Group broke ground on Sloane, a 45-story apartment complex on the site of the former Elephant Car Wash near the Space Needle. The 442-unit tower is, according to the developer, the first residential skyscraper to start construction on the West Coast of the United States in 2024 amid a cooling market.

Mayor Bruce Harrell was on hand for the Sloane groundbreaking to make the case that his Downtown Activation Plan is gaining steam – and that the city’s efforts to boost housing construction (including recent bills to exempt downtown projects from design review and streamlining permits for accessory dwelling units or ADUs) are working.

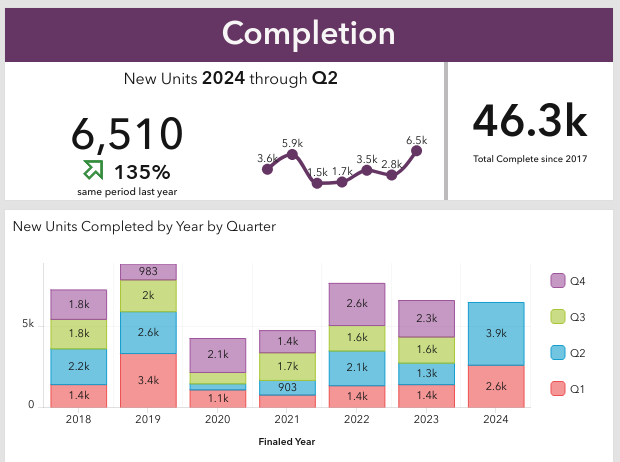

Although Seattle has already produced 6,500 new apartments through the first half of 2024 according to City data, there are troubling signs that permitting and construction of multi-family residential buildings – despite the example of the Sloane project – may be slowing down in Seattle. The stream of projects entering the permitting pipeline is slowing to a trickle, which will eventually force a major slowdown unless applications rebound quickly.

Sloane tower bucks the West Coast downturn in highrises

According to Holland Partner Group, Sloane will be participating in the Multifamily Tax Exemption (MFTE) program and designate 20% of units on-site — 91 homes — for renters earning between 60% and 85% of area median income (AMI). The developer said they will also pay “significant” contributions to the in-lieu affordable housing fund as part of the Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program, Seattle’s version of inclusionary zoning.

The 440-foot tower, according to the proposal submitted during design review by architect Weber Thompson, will offer 2,550 square feet of retail space and have 262 parking stalls. The design review board granted some departures from design guidelines, and there was discussion over improving pedestrian interface with the side of the tower facing Battery Street. Holland Partner Group began the permitting process in 2022 and received approval in September 2023.

“The groundbreaking of The Sloane, on the historic site of the Pink Elephant Car Wash, is exciting news for Downtown Seattle,” Mayor Harrell said in a post on Facebook. “This location, rich in our city’s history, will now bring much-needed housing and space for new businesses, helping to shape the future of our city’s center.”

Parker Dawson, a government affairs manager for the Master Builders Association of King and Snohomish Counties (MBAKS), said the new project is good news in a mixed climate for multifamily housing construction.

“The Sloane building starting to go up right now and delivering a great number of units across a number of income brackets is a fantastic sign that we are still seeing these construction projects get underway in 2024 even in the face of heightened interest rates, rising costs of labor and materials, and continued complexities that building processes can come with.”

Strong production could be last gasp of drying pipeline

Across the nation, there was a post-pandemic surge in apartment permitting and construction that has continued into 2024 despite high interest rates and inflation. According to rental economist Jay Parsons, the US is expected to build a record 600,000 new multi-family units by the end of the year, the highest figure since 1974.

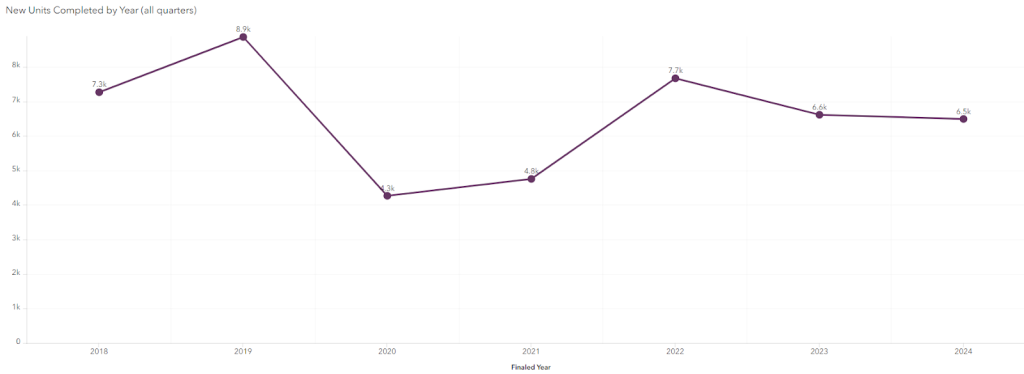

Seattle has been a part of this surge. According to the Seattle Department of Construction & Inspections’ permitting dashboard, Seattle has completed 6,500 new units of multi-family housing in the first half of 2024, beating the 2019 figure of 5,900 units, and just shy of the 2023 total of 6,600 new apartments built.

Spurred by the national surge in production, homebuilders racing to vest their permits before Seattle’s new stricter energy code went into effect in 2022, and easing of ADU restrictions, Seattle also had big production years in 2022 and 2023.

Still, there are troubling signs on the horizon for those hoping that more multi-family housing will begin to address the lack of supply and high cost of rent in Seattle.

“As we continue moving forward with the conditions that I shared – rising costs and persistent building complexities and processes from the city’s end,” said Dawson, “we will see more of a struggle throughout that entire pipeline.”

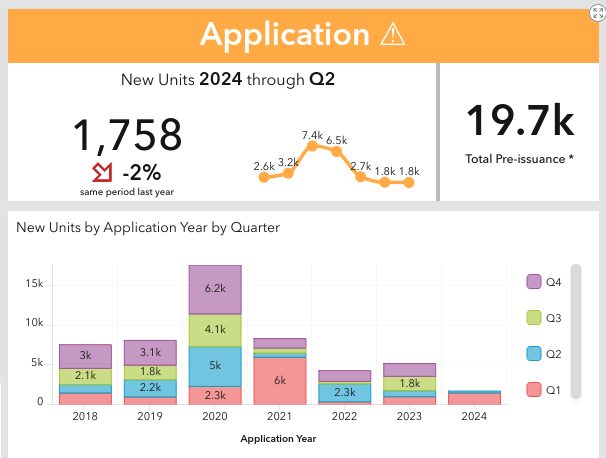

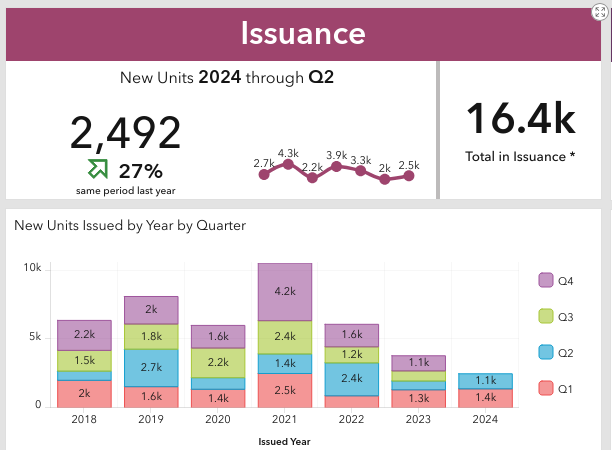

After a surge in application for multi-family permits at SDCI in 2020 and 2021 (reaching a peak of 7,400), new applications for apartment permits have been stagnant in the past two years, with permit applications in 2024 on pace for just 1,800 units, similar to last year.

Assuming a lag time of three years from application to completion of construction, Seattle will see a slump in apartment construction potentially as soon as next year even as the Federal Reserve began lowering interest rates last month. If the permitting pipeline fully dries up, it could take a good while to rectify. Large residential projects tend to take longer to build and sometimes even longer to navigate Seattle’s daunting design review and permitting gauntlet.

Bryan Stevens, a spokesman for SDCI, notes that construction markets are cyclical in nature and that the recent permitting slump is likely to result in slower multifamily construction in Seattle in the near future.

“Permit applications for new housing have been decreasing overall, but especially over the past year,” Stevens said. “Many factors can affect how quickly those cycles change including financing rates, inflation and material costs, and access to labor. Interest rates are a major factor in this and recently hit a 20-year peak.”

Seattle grasps for solutions to spur construction

For its part, the mayor’s office has recently stepped up efforts to boost housing construction, though the upcoming comprehensive plan draft maps, which are expected to be released on October 16, will demonstrate how seriously the Harrell administration takes zoning reforms to increase housing supply. In September, the city council approved Harrell’s bill that would exempt multifamily housing projects in the greater downtown area from design review.

And in September Harrell also introduced a package of reforms further easing ADU restrictions that would bring it in compliance with new state legislation, including increasing maximum size to 1,500 square feet (allowing for 3-bedroom ADUs) and reducing the need for homeowners associations.

But the City’s slow pace reforming design review troubles developers and builders, Dawson said.

“What we’ve often seen is that the lack of objectivity and the lack of a predictable timeline through that process creates an incredible amount of uncertainty that often dissuades investment in a project,” he said. “And where you are able to get started on a project, it can ultimately create delays that last years, and add financial costs to a lender, to a builder, and eventually to a home buyer or a renter.”

Brian Runberg, lead architect at the Seattle-based firm Runberg Architecture, says that while factors such as high interest rates, material prices and labor costs are pushing some developers to shun Seattle, what’s adding to the problem is the expense and uncertainty of design review. His firm used to do about 80% of its multifamily residential design work on Seattle projects and about 20% in the Eastside. In the past decade, that’s flipped to just 20% of projects in Seattle and 80% in places like Bellevue and Redmond.

Runberg said that the flight of tech companies to the Eastside is also driving the decline. “It’s not coincidental that when this migration of the tech business pivoted to the Eastside, so did our clients to provide housing over there.”

He also noted the opening of the new Eastside Link light rail line has made construction of multifamily housing in places like Bellevue and Redmond an easier sell.

But on top of those difficulties, it’s the costly and unpredictable design review process, which Runberg has been a vocal critic of, that’s becoming a deciding factor in causing developers to hesitate in the Seattle multifamily housing market.

“You have a design review process that five years ago might have taken 12 months and creeped up to 18 months, and then it was 24 months, and now it’s 30 months,” Runberg said.

“The folks that put up 90% of the financing for these projects are out-of-state investors, and if they see the risk is too great, that it takes too long to put it together, or the process is too complex, it all adds risk,” he said. “And they’re going to lend less on these projects if this happens repeatedly. You start to get the bad reputation that we’ve got – that it’s a risky market.”

Runberg cites two examples of projects he was personally involved with that failed to complete construction because of design review squabbles. One, a 134-unit apartment building at 12th Avenue and Olive Way, burned through at least 2,700 hours of the firm’s time on the 21-month design review process, adding at least $400,000 in extra costs to the transit-oriented development. Existing housing was demolished, but cost pressures eventually forced the developer to back out.

“It was, sadly, one of the ones that the clock ran out when interest rates tipped,” Runberg said. The lot now sits vacant.

Another of Runberg’s projects, at 118 W Mercer, would have created 113 new units of housing. Runberg said outreach by the architect and developer generated overwhelming support from the local Uptown Alliance, but the project soon bogged down in a 21-month delay before the West Design Review Board. Runberg said the process added more than 1,600 hours of his firm’s time to the project at a cost of at least $250,000. Despite community support, the board pushed for numerous changes to the project, Runberg said.

“There was also turnover on that board that made it even more convoluted and confusing,” Runberg said. “As a consequence, the existing apartment building was torn down, and the Tup Tim Thai restaurant demolished. Here we are four years later with an empty site and the project is effectively mothballed. It didn’t make economic sense.”

Runberg also notes one additional pressure on apartment construction in Seattle. While he agrees that setting high energy efficiency standards is an admirable approach to addressing climate change, he believes the city of Seattle set extremely high goals with little attention paid to how those standards would impact costs or the pace of construction.

Those new building standards, which Runberg said are now the most restrictive in the nation, add additional costs on to projects already burdened by interest rates, materials, and labor costs. His industry lobbied the City to stick with Washigton state’s new standard, already the nation’s most stringent, but the City was committed to topping that by 10 to 15%, he said.

In response, Mayor Harrell recently proposed rolling back tighter energy code requirements to spur homebuilding.

“It will be really onerous, for the industry to try and dig ourselves out of the hole we’re in,” Runberg said. “Nobody wants global warming. We all want to get there. But, it’s a big, complex thing. It’s like trying to turn an aircraft carrier. You can’t spin the wheel that fast.”

Correction: Brian Runberg was misspelled in the original draft. We apologize for the error.

Andrew Engelson

Andrew Engelson is an award-winning freelance journalist and editor with over 20 years of experience. Most recently serving as News Director/Deputy Assistant at the South Seattle Emerald, Andrew was also the founder and editor of Cascadia Magazine. His journalism, essays, and writing have appeared in the South Seattle Emerald, The Stranger, Crosscut, Real Change, Seattle Weekly, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Seattle Times, Washington Trails, and many other publications. He’s passionate about narrative journalism on a range of topics, including the environment, climate change, social justice, arts, culture, and science. He’s the winner of several first place awards from the Western Washington Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.