One month after The Urbanist published an extensive investigative report detailing the Seattle Police Department’s (SPD’s) use of mutual aid during the 2020 protests, SPD’s Chief Operating Officer Brian Maxey and General Counsel Rebecca Boatright met with Office of Inspector General (OIG) staffers, determining that the OIG would “terminate” an audit of SPD’s use of mutual aid.

According to the OIG, “mutual aid refers to assistance provided to law enforcement agencies by other departments. Agencies provide personnel, equipment, and other resources to support emergency response and management of large-scale events.”

As The Urbanist reported, SPD’s use of mutual aid during the 2020 protests exploited a policy loophole, deploying dangerous and toxic weapons via partner agencies with little to no accountability — even though SPD officers were banned from using those weapons themselves.

Boatright, Maxey and OIG staffers decided to terminate a Generally Accepted Government Auditing Standards (GAGAS) audit that had been identified and planned in 2019, almost four years previously.

OIG’s audit webpage highlights that “a key characteristic of OIG GAGAS audits is independence. Independence means the freedom to do work and come to conclusions without influence or bias affecting the result. The police accountability ordinance established OIG as an independent office in order to remove outside influence on OIG work products.” The City of Seattle established the OIG with the goal of addressing issues identified in Seattle’s consent decree process launched in 2012, such as documented patterns of misconduct and racial bias.

Audits are a key tool for OIG to achieve that aim and the agency’s webpage states that GAGAS methodology is imperative to ensuring quality work: “OIG auditors follow standards to make sure that findings are supported by sufficient and appropriate evidence,” and to ensure that OIG’s “work is accurate and robust… GAGAS are the standards that ensure that audit reports are unbiased and can be trusted to be truthful and accurate.”

In December of 2019, an OIG Work Plan stated the office had already initiated an audit into SPD’s use of mutual aid. One year later, the OIG was still in the process of conducting the audit. According to their 2021 work plan, the scope of the audit had expanded to “include an assessment of interactions with mutual aid entities during the 2020 mass demonstrations.” OIG predicted the audit would be issued in the second quarter of 2021. However, the audit never came.

In lieu of using GAGAS methods, OIG opted instead to produce a nebulous “review” of SPD’s use of mutual aid. Notes taken at OIG’s meeting with Boatright and Maxey state that OIG would interrogate mutual aid officer’s use of force reporting while in Seattle. However, OIG’s final review does not.

Why did OIG not follow through with GAGAS in this case, and does that signify the OIG’s review was not independent, not accurate, and not robust? OIG did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

OIG’s review of SPD mutual aid

In July 2024, four and a half years after identifying the intent for an audit, OIG released a six-page report titled “Review of SPD Mutual Aid Practices.”

OIG identifies the King County Interlocal Agreement, signed in 2005 as the primary regional mutual aid agreement in effect with SPD. Other “notices of consent” signed in 2012, allow multiple other law enforcement entities the consent to operate within the City of Seattle.

SPD has also been called out as mutual aid to assist other jurisdictions across Washington State. According to data transmitted from SPD to OIG, SPD has been requested to assist other jurisdictions 24 times between 2014-2023. This number does not take into account SPD’s deployment and participation in federal task forces, such as the Pacific Northwest Violent Offenders Task Force, where an SPD officer shot and killed a man while operating outside of Seattle in Kent in 2022.

When it comes to external agencies operating within Seattle, according to data transmitted from SPD to OIG, SPD has made 31 requests for mutual aid between 2014-2023.

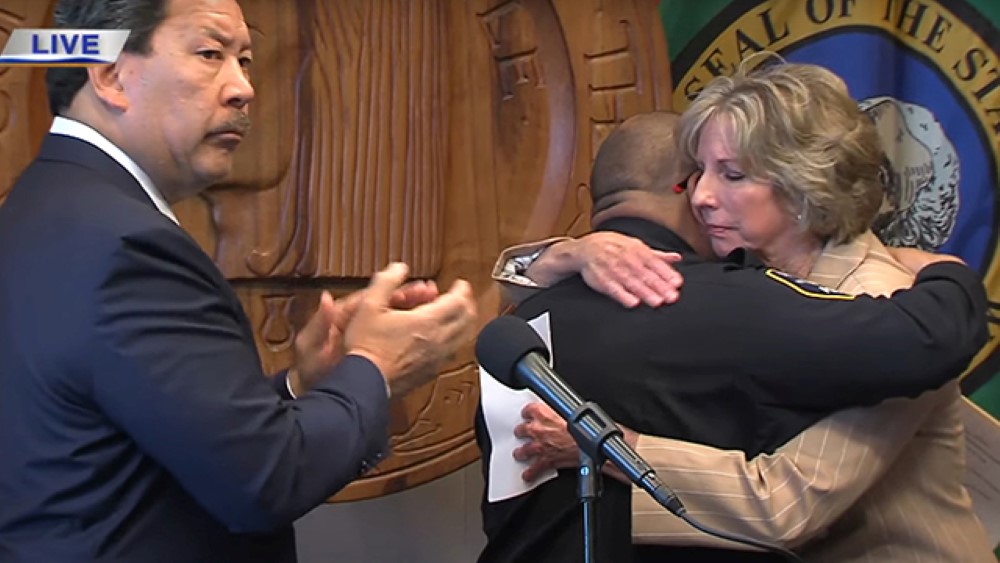

One SPD request for 15-20 King County Sheriff (KCSO) Deputies to patrol and respond to 911 calls throughout Seattle was made because then SPD chief Adrian Diaz was planning for Seattle “911 services to be significantly impacted,” due to a massive funeral service planned for fallen SPD officer Lexi Harris on July 1, 2021.

OIG’s mutual aid review did not assess if KCSO deputies responding to Seattle 911 calls and patrolling the streets of Seattle would be required to follow SPD bias policies, be held to SPD force review policies, and be accountable for their actions through the Office of Police Accountability (OPA) complaint process.

OIG’s mutual aid review also stated that “the records [provided by SPD] were limited in their completeness, detail, and consistency of information included, thus limiting the ability of OIG to review and make recommendations for future agreements or department policy.”

It’s unclear if OIG took any steps to remedy the incompleteness of information they received from SPD. Previous reporting by The Urbanist included detailed information that was omitted from OIG’s review, including use of force statistics and after action reports made by responding mutual aid agencies, which OIG claimed not to have access to.

“SPD does not appear to retain records documenting what occurred during mutual aid operations, including deployed units, officers, and resources, actions taken, injuries to subjects or officers, and any costs incurred. This lack of documentation limits the ability of SPD to review the outcome of planned mutual aid operations, and creates potential issues related to resource management, force reporting, and injury liability.”

OIG’s mutual aid review ends with a note stating that minor reforms to SPD’s mutual aid practices are “especially critical as the city prepares to host an estimated 60,000 tourists for the World Cup in 2026.”

OIG also recommended that SPD should “attempt” to update their old mutual aid agreements with new terms and policies, that SPD should improve recordkeeping, and that when SPD sends officers to another jurisdiction, SPD should update their policy to explicitly require officers to follow SPD policy, when they might conflict with the policy of another jurisdiction.

Internal OIG documents, obtained through a public records request, show that “outgoing [SPD] mutual aid requests did not state any policy requirements for policing within the City of Seattle.”

An internal SPD email from 2020 also shows that external “Mutual aid SWAT teams would not work in Seattle without a letter from the Chief allowing them to use their less lethal [weapons] in an emergency.” SPD recommended the City keep that policy in place, continuing to allow extensive weapons to be used on Seattleites that are prohibited under SPD’s own policy.

“Less lethal” weapons is a term used by police which includes a range of chemical agents and projectiles, including pepperball launchers, 40mm projectiles, blast grenades, pepper spray, tear gas, and other chemical agents. Each type of weapon is “less lethal” than a firearm, but far from harmless. In multiple cases, “less lethal” weapons have resulted in debilitating injuries and in death.

The SPD public affairs team declined to answer detailed questions about mutual aid policy, they did tell The Urbanist that “just as SPD officers must follow our department policy when providing mutual aid, officers from other departments follow their department policy.”

In practice, this has allowed external law enforcement agencies, to use lethal chemicals, such as Washington State Patrol’s use of hexachloroethane (HC) smoke, in addition to hundreds of uses of force within Seattle with no use of force reviewed by SPD and OPA complaints about mutual aid law enforcement conduct immediately closed and handed off to other jurisdictions. None of this was investigated within OIG’s mutual aid review, which noted that in the past 10 years, all SPD requests for mutual aid “were for additional personnel to support crowd management activities during protests and other planned events.”

As OIG is slated to take on a “substantial” independent monitoring role of SPD after the conclusion of Seattle’s consent decree, the OIG’s mutual aid audit provides a window into the OIG’s process.

In the end, an official audit, identified and planned for almost five years, was downgraded to a “review,” omitted considerable information, and was placed “on the backburner” while it was apparently sent to SPD for feedback prior to public release.

The status of civilian oversight of SPD and the City of Seattle’s “commitment to sustaining OIG operations” will be discussed at an October 16, 2024 consent decree status conference in the U.S. District Court in Seattle. Since the Durkan Administration, the City of Seattle has sought an end to the consent decree and the federal oversight of SPD that it brings, but so far has failed to reach full compliance — in part due to cracks in its local police accountability system.

Glen Stellmacher (Guest Contributor)

Glen Stellmacher is a licensed architect. He is a graduate and former lecturer at the University of Washington. His work can be found around Seattle and in print within Advancing Wood Architecture: A Computational Approach, Trajectories, a compendium of research on robotics, digital design, fabrication and sustainable forestry practices and online.