A debate is brewing over a relatively obscure framework that has a sizable impact on transportation planning in central Puget Sound, setting the stage for decisions that affect how over four million people get around every day. The heart of the issue is whether an update due in 2026 to the Regional Transportation Plan, covering the entirety of King, Pierce, Kitsap and Snohomish counties, will include a significant change in course.

Elected officials from around the region will be spending the next year debating issues and questions that the plan should answer — but some of those officials are calling for the update to be much more ambitious than otherwise planned.

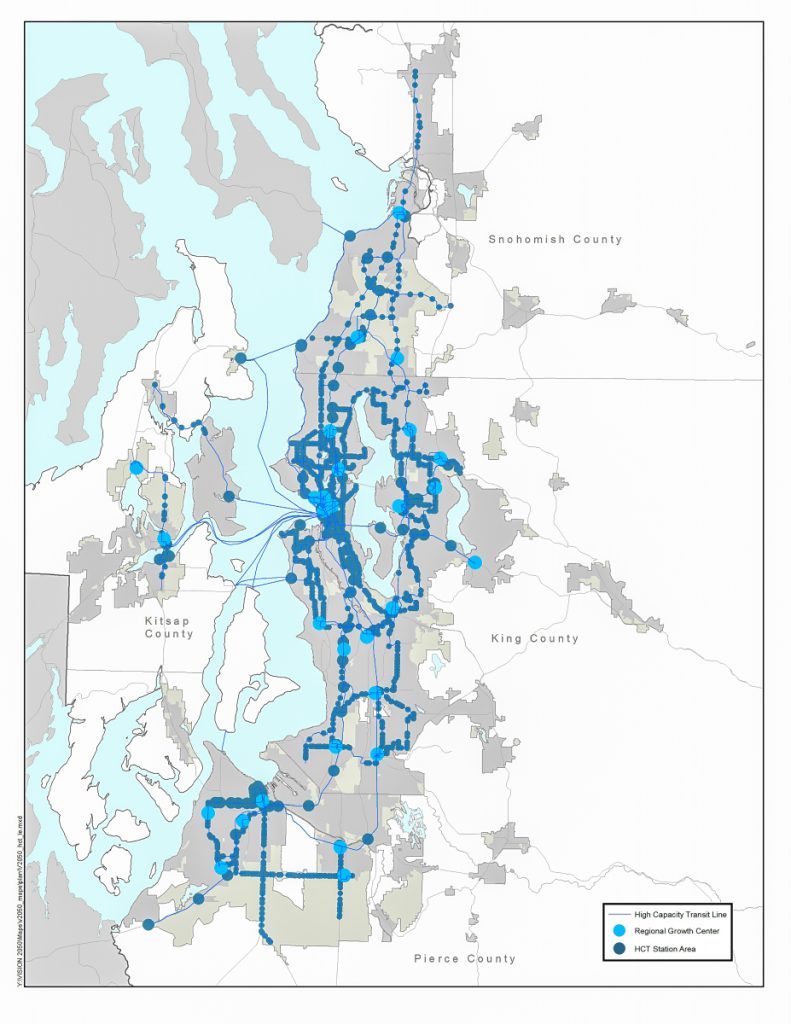

Approved by the Puget Sound Regional Council as an implementation strategy for the region’s land use plan, dubbed Vision 2050, the Regional Transportation Plan (RTP) sets priorities for transportation investments over the next two decades, crafting overarching policies guiding future grant awards. The environmental analysis at the heart of the plan hasn’t been fully updated since 2008, with each four-year update to the RTP simply amending the existing analysis and updating its assumptions. The 2026 update could be a chance to change that and do a more substantial overhaul.

The 2022 RTP that is currently on the books was set to have been a “major” update, redoing the environmental assessment conducted. But given the timing of that plan’s creation — in 2020 and 2021, just as remote work and reduced transit usage were upending the entire country’s transportation system — a major update was postponed. That fact is noted in the very introduction to the plan itself.

“By the time the next Regional Transportation Plan is due, the regional transportation system and the region’s transportation needs will be significantly different than today,” it notes. “Specifically, the expansion of the high-capacity transit system, the changes in regional travel patterns due to the pandemic and the increase in remote work, continued regional growth, the climate crisis, and the significant changes in the federal and state funding environment mean that the next RTP will need to respond to a different set of challenges and opportunities. To do that, the next RTP should be prepared as a major update that includes environmental analysis.”

With the scope of that plan being developed now, it’s not clear if that update will actually be as major as promised. In September, following a presentation on the plan update to the PSRC Executive Board, King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci, president of PSRC from 2021 to 2022, noted that it looked like the organization was headed toward a status-quo update, if they didn’t change course.

“When we adopted the current transportation plan, we unanimously added some direction about the next plan, and have not heard a peep about it ever since,” Balducci said at that meeting. “We also said that there was a work plan item to explore how we could transform how we do our planning, because we just keep [it] doing the same way over and over and over again. And there are options. There are alternatives out there that could be more transformative — maybe briefer? — but more impactful.”

Josh Brown, PSRC’s Executive Director, jumped in to note the significant challenges that the plan is expected to tackle. “I absolutely think we’re going to have a major update to this plan,” Brown said.

But Balducci noted that a major update requires PSRC to do certain things, namely update its environmental analysis. And Balducci’s comments were backed up by other board members who were pushing for the plan to do more.

“I have sat on this board since 2016, and since 2016 I have been waiting for a major update, a major redo of the transportation plan — it’s time,” WSDOT Secretary Roger Millar said in response to Balducci’s comments. “When you look at the revenue problems we have, when you look at the information we’re gaining on human behavior coming out of the pandemic, when you look at the safety crisis […] We have an opportunity, I think, to link land use and transportation. The minor updates we’ve done have always been: we’ve got a land use plan, we’re going to do a transportation [plan] — I think there needs to be another variable in that conversation, which makes it a major update.”

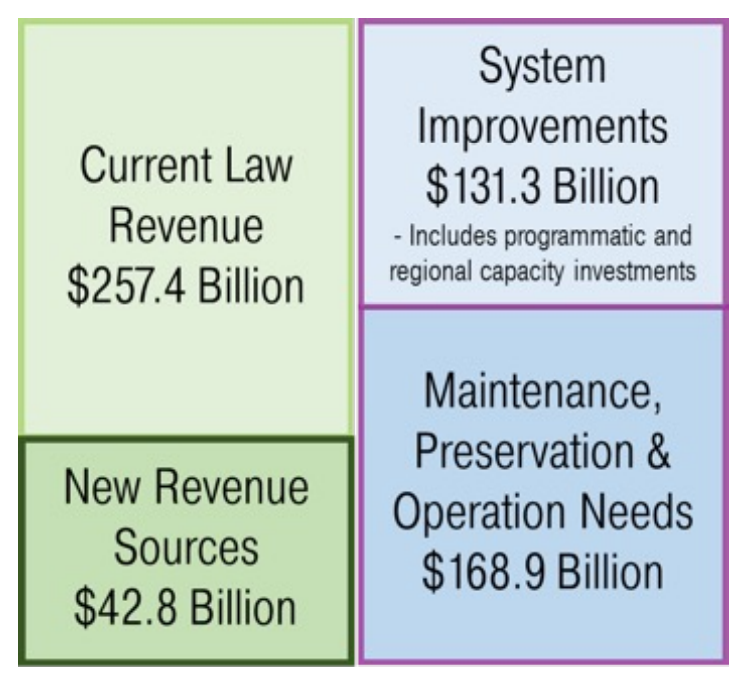

One of the biggest things the plan will tackle is a financial strategy to fund the transportation investments the plan relies on. The current RTP has a $42.8 billion gap between what’s needed and the funding sources that Washington currently has in place to fund transportation. It also assumes that the Washington State Legislature will pass a road-usage charge (RUC), a per-mile fee on vehicle travel intended to be a long-term replacement for the state gas tax as the share of electric vehicles continues to increase, as a way to bridge that gap.

Politically dicey to say the least, the idea of a RUC has struggled to advance at the legislature, even at a rate that would be roughly equivalent to what drivers are paying in gas tax currently, around three to four cents per mile. But the RTP assumes a future road-usage charge would actually go even further, charging drivers 10 cents during peak times of day and five cents off-peak. The plan also assumes that any funds from a RUC would be able to be spent broadly across transportation, unlike the current restrictions on gas tax revenue baked into the state constitution that require spending on “highway purposes.”

“I think that the amount of work, especially around revenue, is going to be major, and I’m not sure that we’re set up given the timeline to have the discussions that we need,” Jay Arnold, Kirkland’s Deputy Mayor, said. “I think as we look at what the revenue is needing to meet our long term transportation plans and how we tie in some of the goals, like climate, I think we need to have a much more robust discussion around revenue sources.”

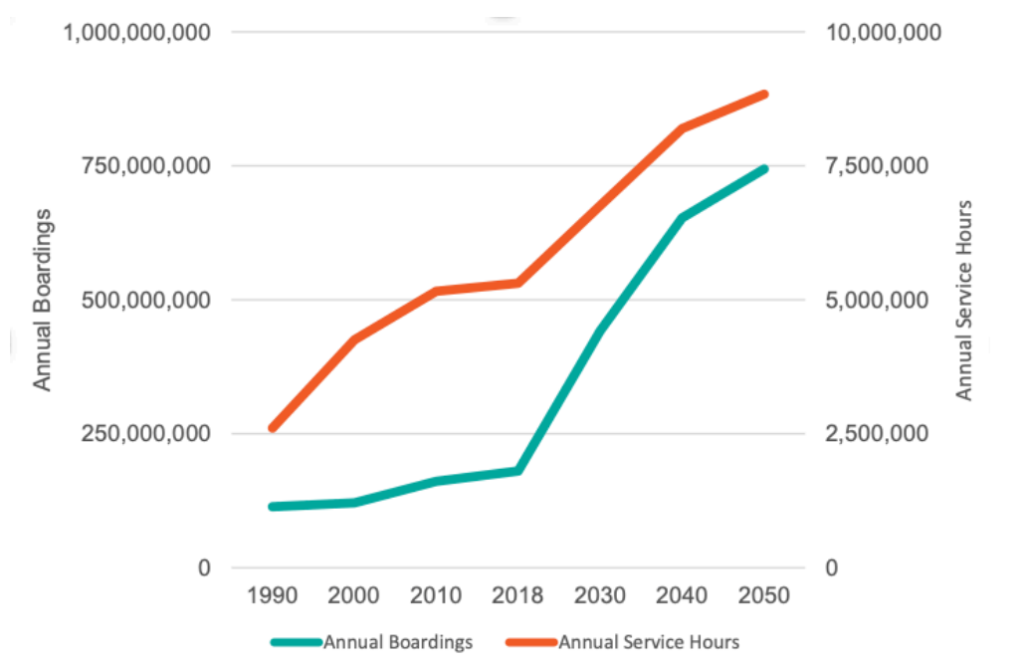

Out of that $42.8 billion, it’s actually not local cities, counties, or the state that is expected to rely on that future revenue the most — it’s transit agencies. The RTP projects a $21.9 billion shortfall at the region’s transit agencies, in large part because because the plan expects transit boardings to triple by 2050 across the entire region — and for the service hours provided by agencies to climb accordingly. But they can’t do that without new revenue, and are already expected to bear a disproportionate share of the burden if I-2117, repealing the 2021 Climate Commitment Act, is approved by voters this November.

As the head of a state agency facing its own significant transportation funding challenges, Millar put forward the idea that the update to the RTP should be an opportunity to reassess things like how the region treats issues like work-at-home rates and the future of Downtown Seattle, not as a 9-5 jobs center but as a 24/7 neighborhood. He also brought up the idea of taking a public health approach to reducing serious injuries and fatalities caused by the transportation system.

“And when you have a public health problem, the first thing you do is separate people from the problem,” Millar said. “And if cars are the problem, can we in our transportation plan find a way to support a robust economy, to address the quality of life issues of people here, to address the environment by land use patterns that reduce our reliance on the automobile?”

The state transportation secretary argued the transportation industry was facing a major inflection point.

“But can we have a conversation about those bigger issues?” Millar continued. “We haven’t, in my experience, in this position, and I think it’s about time, particularly with the financial problems that we see — depending on what happens with the ballot initiatives, depending on what happens at the national level with the election, we’re going to be in a different world, and I think we need to be thinking big on that, as opposed to retrenching and just finetuning what we’ve got.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.