We all want better access to more affordable homes, but Seattle has too few homes coming out of the pipeline to meet demand. One of the blockages leading housing applications to slow to a trickle is a new rule that Seattle Public Utilities (SPU) adopted in 2020 called WTR-440. Snaking out that rule from the pipe won’t solve the housing affordability crisis overnight, but it will remove a barrier to constructing homes of all types without affecting public safety or access to the clean and plentiful water that we all rely on.

As the Seattle City Council prepares to discuss Mayor Bruce Harrell’s proposed budget, which includes consideration of SPU’s proposed budget, Seattle’s leaders can work to re-evaluate WTR-440 and re-establish council oversight of SPU’s operations to ensure compliance with state and federal law and that code interpretations and Director’s Rules at the department level do not contradict or impede Seattle’s housing goals in the future.

The city’s water system is complex and the result of years of important public investments, as well as some unfortunate periods of neglect. According to the Seattle 2019 Water System Plan, the city’s water mains have an average age of 71 years. That’s why SPU is prioritizing the modernization of this water system for current residents and expected growth in our region.

The costs of these water system improvements are closely tied to Seattle’s housing supply and affordability crisis. However, SPU is requiring Seattle homebuilders to take on an increasingly large portion of these improvements. This shift has sharply reduced the viability of constructing new housing across the city. Further, it has astronomically driven up the price of homes that do get built and will continue to do so. Essentially, we are telling prospective homebuyers that they need to pay for fixing pipes that the City has neglected for decades.

The root of this issue can be directly tied to a policy shift at SPU that was implemented in 2020 during the COVID-19 pandemic and therefore went all but unnoticed by lawmakers, homebuilders, and the public.Director’s Rule WTR-440 gives the SPU Director discretion to require improvements to Seattle’s water system as part of any construction project regardless of the impacts and water demand the project would have on existing system capacity.

WTR-440 created a series of discrepancies between Seattle’s policies and state law.

At its inception in 1990, Washington State’s Growth Management Act (GMA), a law governing how local governments must plan for and accommodate new growth, foresaw the inevitable friction between rising water demand and the maintenance of public infrastructure.

To ensure cities, towns, and counties could always accommodate growing populations and jobs, one of the GMA’s planning goals is that local jurisdictions must construct “public facilities and services necessary to support development.” To that end, local comprehensive plans must have a capital facilities plan element that details, among other things, an inventory of existing infrastructure, “a forecast of the future needs” of that infrastructure, and a six-year plan to finance new or improved infrastructure “within projected funding capacities and clearly identifies sources of public money for such purposes.”

This means that the GMA requires local governments like Seattle to project future demand on city systems – like water distribution mains – and identify public funding sources to ensure that utility systems are always in a state where development like new housing can be accommodated to meet local needs.

This is consistent with state law recognizing that new development can and should be required to pay an equitable share of new infrastructure but cannot be leaned on as the primary funding source or to correct a funding deficiency.

Dating back to the 1990s, the Seattle Municipal Code (SMC) required “construction of a standard water main” in front of any new home before it could be connected to the city system. However, constructing these water mains was sometimes infeasible or cost prohibitive for SPU to reasonably provide during the time of development. In these cases, homebuilders were allowed to construct a direct “service line” to connect a new home to an existing nearby water main.

Beginning in the early 2000s, however, SPU policies began to shift financial and operational responsibilities for system upgrades even though there was no change in code language or state law. Rather than planning for and identifying sources of public funding, as the GMA requires, SPU placed the financial burden on property owners and homebuilders to fund and correct shortfalls in the city’s water distribution system.

SPU has replaced a publicly funded water system plan with WTR-440’s discretionary placement of water system requirements on new development. The effect of this policy shift has been insufficient emergency preparedness, a housing affordability crisis, and a neglected citywide water system.

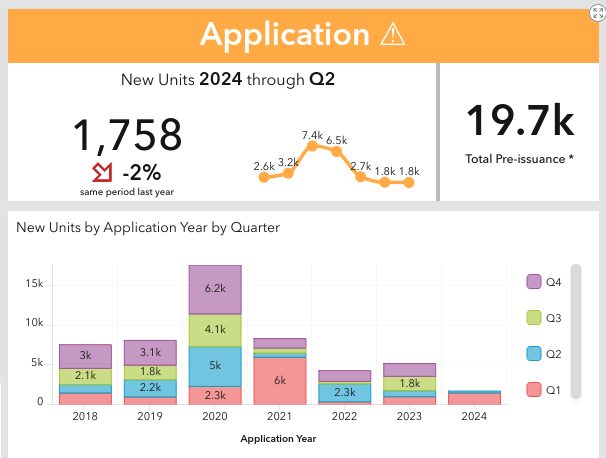

The cost prohibitive nature of these requirements has stopped a growing number of homes from being built in Seattle. There are thousands of examples from SPU’s own Water Availability Certificate (WAC) data – the permitting tool with which WTR-440 imposes these infrastructure requirements.

Without an approved WAC, builders cannot break ground on their projects. And since SPU can spring water availability issues on applicants late in the process, the homebuilder might end up spending tens of thousands of dollars designing and permitting a project that ends up being infeasible after being hit with surprise fees. The unpredictability of this process encourages some builders to look elsewhere to site their projects, especially if they’ve already had a bad experience with unexpected costs imposed by SPU.

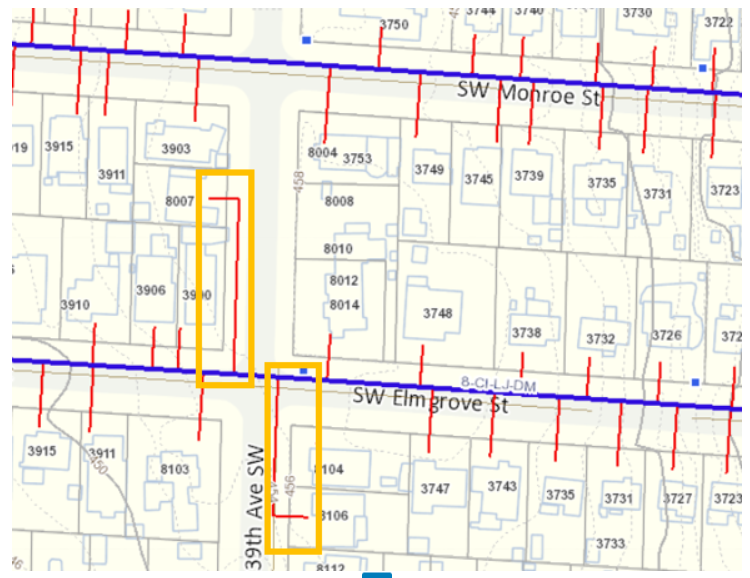

One project, a home with two backyard cottages proposed in Phinney Ridge, was denied a WAC unless the homebuilder replaced 500 feet of aging water distribution main with new earthquake-resistant pipe. The cost of this upgrade – prior to the additional costs of rebuilding the street following pipe installation – came with a forecasted price tag of $750,000. With water main work rivaling the cost of construction of the cottages themselves, this killed the project.

Backyard cottage and other accessory dwelling unit (ADU) projects are especially susceptible to being killed by utility costs since most small-scale builders have little cushion in their budgets. Only 37% of ADU permits submitted to Seattle between 2017 and 2021 resulted in a completed building, according to Alex Czarnecki, founder of Cottage, a platform that assists with ADU construction. If left unaddressed, this utility issue could undermine the City’s efforts to encourage ADU construction with reform legislation.

Another project sought small renovations for a new daycare center in Lake City, but SPU required installation of a 16-inch valve and other upgrades that can cumulatively cost upwards of $120,000. While the Seattle City Council has passed legislation encouraging daycare creation across the city, SPU did not get the memo on that policy goal.

SPU’s application of WTR-440 to require water system upgrades is limiting housing from being built and increasing costs of homes that make it through this arduous permitting process. SPU’s data shows that from 2017 to mid-2023, over 1,600 WAC applications were denied pending water system improvements that extend beyond the direct impacts of the proposed projects on Seattle’s water system.

Those denied WACs represent approximately 5,000 homes that went unbuilt in the past five years due to the costs of SPU’s requirements according to SPU data. The consequences of staying the course, of requiring new housing to underwrite broader system improvements, will result in more expensive housing across the board, in a growing disparity in access to housing, and in a continued trend of providing too few homes for Seattle’s current residents, newcomers, and future generations.

There is hope. The Mayor and City Council have a chance in the current budget process to refocus SPU toward identifying sustainable public funding sources that respond to our growth needs and limitations. Meanwhile, Seattle is developing its updated Comprehensive Plan and implementation of the middle housing state law, House Bill 1110. The culmination of these two legislative processes represents the single greatest opportunity to address the housing crisis in our region since the inception of the GMA itself.

Acting on these opportunities can set Seattle on a path to support our thriving economy with the housing our city urgently needs.

Donna Breske (Guest Contributor)

Donna Breske is a licensed Professional Engineer in the State of Washington. She owns Donna Breske & Associates and with her staff provides land use consulting and civil engineering design for numerous infill projects within multiple jurisdictions in the Puget Sound Area. She has a Bachelor of Science in Civil Engineering from the University of Washington and an MBA from Seattle University. She is married to her husband Fred with whom they share two adult children. She grew up in Seattle and is passionate about eliminating absurd impediments from permitting departments and ensuring consistent and predictable outcomes.