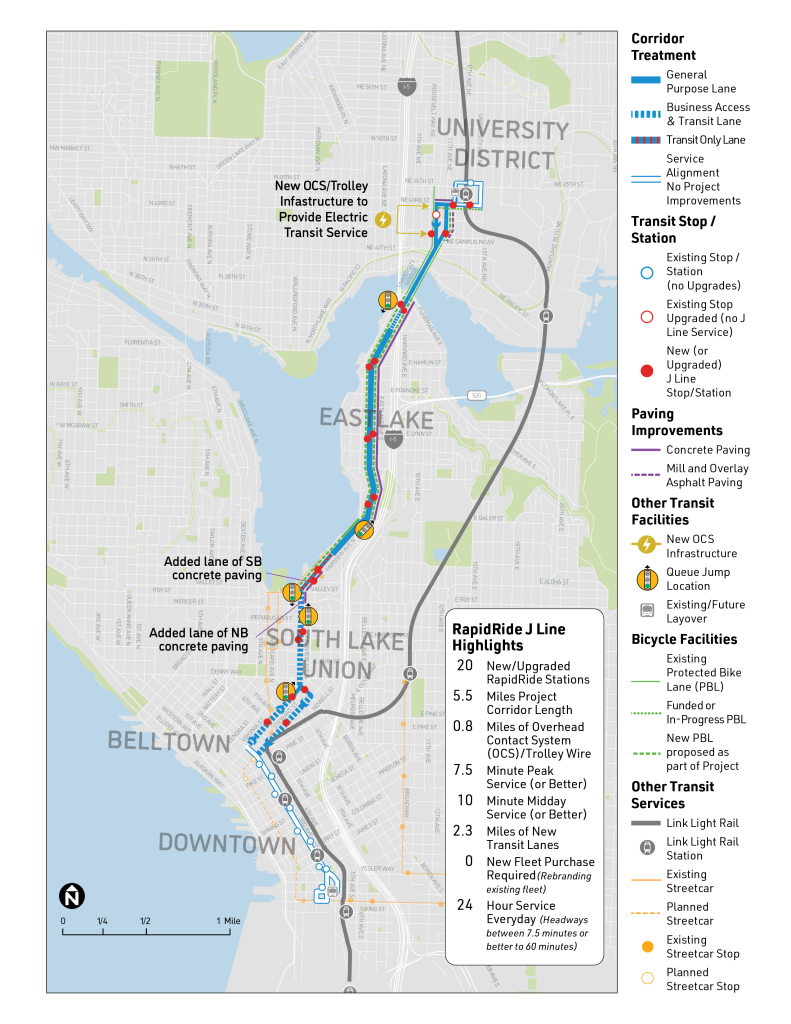

On Tuesday, Seattle and King County leaders officially broke ground on the next RapidRide bus rapid transit (BRT) project within Seattle’s city limits: the J Line through South Lake Union, Eastlake, and the University District. The $128 million project is expected to open in 2027 as the first RapidRide project operating using electric trolleybuses.

Work to build the J Line will include full street reconstruction up and down the corridor, most of which will replicate the existing Route 70. Protected bike lanes will be added to Eastlake Avenue E, filling a critical and conspicuous gap in Seattle’s bike network, along with nearly 9,000 feet of new water main, 131 upgraded curb ramps, and dozens of blocks of repaired and upgraded sidewalks.

Improving a key bike and bus corridor

The long road to get to the point of groundbreaking has been contentious, with considerable opposition to RapidRide J from within the Eastlake neighborhood over plans to reallocate most of the curbside parking spaces along Eastlake Avenue E to make room for protected bike lanes.

After the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) spent considerable effort looking at alternative ways to provide bike connectivity along Eastlake, former Mayor Jenny Durkan put her full support behind the proposal to finally connect Eastlake — and much of Northeast Seattle — with a safe and accessible bike route to Downtown.

“The RapidRide J Line is a crucial connection for people who bike in Seattle,” Lee Lambert, Executive Director of Cascade Bicycle Club, said in a statement. “In 2019, about 1,700 people crossed the University Bridge by bike daily, making it the second-busiest bike route in the city. By improving Eastlake Avenue, we’re not just enhancing safety for people who bike, but we’re also supporting a vision of Seattle where bussing and biking work together to move people more efficiently, safely, and sustainably.”

The Route 70 carried more than 8,000 daily riders in 2019, but it was hard hit by pandemic losses and has been slow to regain ridership with pandemic era travel patterns and the opening of light rail between the U District and Downtown in 2021. Recent weekday ridership on the 70 has hovered around 5,000, but the project’s grant application with the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) notes an aspiration to achieve over 16,000 daily riders by 2035, thanks in part to improved travel times brought on by bus-only lanes along the route in South Lake Union and at a frequent choke point south of the University Bridge.

In his remarks, King County Executive Dow Constantine gave a nod to the collaboration between Metro and the City of Seattle, noting the project “puts riders first” and would “make boarding easier, make riding faster and make travel safer, safer and more comfortable.”

“The Route 70 already accommodates a passenger load comparable to that of a RapidRide line. So it’s time to make this upgrade official and transform this route into the improved bus service, the enhanced transit service, our communities deserve,” Constantine said Tuesday. “The J line will expand transit access, give more people reliable, smoother journeys, whether they’re heading to work or medical appointments or other important destinations, like class.”

The long, winding road to groundbreaking

The concept for the J Line originated in Seattle’s 2012 Transit Master Plan, which prioritized upgrading the existing bus corridors between Downtown and Northgate, connecting riders to three of North Seattle’s planned light rail stations while at the same time as providing direct connectivity to South Lake Union. But getting all the way to Northgate was initially deemed too ambitious and a terminus at Roosevelt Station was settled upon in 2015, with the project taking on the moniker Roosevelt RapidRide.

The campaign for the 2015 Move Seattle Levy, which promised to fund seven RapidRide lines, had initially pledged a 2021 opening date for the J Line, but planning delays and headwinds from a transit-averse Trump Administration set the project back. The J Line fared better than Route 40, 44, and 48, three corridors that saw their RapidRide plans canceled in 2018.

In 2020, facing a budget crunch prompted by the pandemic, the route was shortened and delayed yet again and the northern terminus was changed to U District Station.

During that extended planning period, the project faced considerable headwinds from a number of businesses and residents in Eastlake who argued that the project was unneeded and that removing parking would have a devastating impact on the neighborhood. The Eastlake Community Council became a particular nexus for opposition to the project, with the leadership in that group going so far as to eject board members who supported the project as recently as last year, after the J Line had already reached full design.

The Move Seattle Levy provides the bulk of the City’s $43 million contribution to the project. The federal government is providing $64.2 million via a Federal Transit Administration Small Starts grant and an additional $9.6 million from the Federal Highway Administration. The Washington State Department of Transportation and the University of Washington will each contribute $6 million. Seattle Public Utilities is funding water main work to the tune of $28 million. King County Metro is contributing more than $10 million toward bus station amenities and staff resources, in addition to operating the line, officials noted.

Managing construction detours and risk of defects

With three long years of construction ahead, the hard part is just beginning for RapidRide J.

This week’s ceremony comes as SDOT and King County Metro manage the continued rollout of Seattle’s most recent BRT project, the G Line, which launched in mid-September. With a whole slate of new features unique to Metro’s network, G Line riders have encountered a number of hiccups in the route’s first weeks, as Metro broke in a new bus type to its fleet with doors on both sides (to accommodate center bus lanes) and worked to hit the ambitious goal of providing six-minute frequencies for most of the day.

After The Urbanist reported on the work happening behind the scenes to get things right on Metro’s end, the Seattle Times reported this week that a slew of construction defects will require repair on SDOT’s end, including bus platforms that are an inch too high for ADA compliance and shelters that will need to be repainted to meet their expected lifespan. Officials declined to point blame in the local paper of record.

Jansen also won the bid for the J Line and was awarded a $82.6 million construction contract in June.

Pioneering fewer new features, the J Line is more familiar territory for both Metro and the City of Seattle, and the travails of the G Line have surely provided some fresh lessons that can be applied to future projects. Asked about the fixes that SDOT is making to the G Line stations after they’re open, SDOT Director Greg Spotts portrayed them as business-as-usual and pushed back on the idea that there was a quality control issue with Jansen’s work.

“I wouldn’t say that it’s actually unusual to have a punch list at the end of a complex project,” Spotts said. “I’m not ready at this time to say that it’s a quality defect per se, particularly the bus platform issue [which] is such a small tolerance and it’s something we haven’t tried before, so it could be a normal part of the commissioning process to make adjustments, so I don’t see that as sort of a sign that we’re having trouble.”

The repairs will mean a few more weeks of construction impacts on Madison Street, and it’ll mean disruptions for G Line riders since the punch list is being tackled after service launch.

“I would actually say that the system worked in that a workaround was developed so that we could open the line on time,” Spotts said.

Construction along Madison Street to build the G Line was a slog for residents and businesses alike, with major street closures lasting weeks at a time in multiple stages. Earlier this year, SDOT told The Urbanist that the agency plans to minimize construction detours and maintain existing bus service along Eastlake, which has very few parallel routes that can handle significant traffic volumes.

The J Line is set to be Seattle’s last new RapidRide line to open during this decade, with the R Line upgrading Route 7 along Rainier Avenue currently not set to open before 2031. Beyond that, the Route 36 is the Seattle bus route most likely to get the RapidRide treatment, according to a new RapidRide prioritization report commissioned by the King County Council. Seattle’s next transportation levy, which is about to go to voters this November, did not make firm promises when it came to transit corridors or whether more RapidRide upgrades would be in store.

Meanwhile RapidRide I Line, between Renton and Auburn, is currently at 100% design and set to open before the J Line as soon as 2026, and the next RapidRide line on the Eastside, the K Line between Kirkland and Bellevue, is on track to open by 2030.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.