Mayor Bruce Harrell’s proposed 2025 budget includes many cuts and layoffs to finance a 16% increase to the police department.

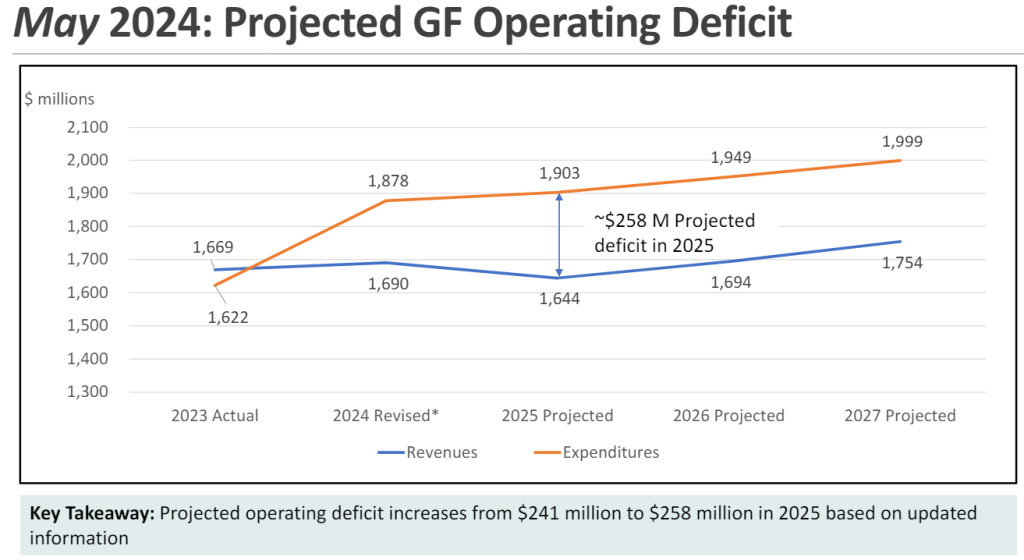

Mayor Bruce Harrell’s budget proposal, released in late September, patches a quarter-billion-dollar deficit, but it also revealed much about his priorities for the future of Seattle, and it should be cause for concern for those hoping for an inclusive Seattle rather than a city for the rich.

While Harrell balanced many investments with calculating political savvy – for example, by funding both an expansion of the Unified Care Team that performs homeless encampment sweeps and keeping a shelter open that was previously funded by one-time federal dollars – his overall vision for the city remains focused primarily on a punitive whack-a-mole approach to public safety and homelessness that does little to chart a lasting resolution of the serious problems at hand.

The budget pledges temporary relief and no new taxes for the well-heeled citizens of Seattle that were the core base of support for the mayor and the centrist majority on city council.

Temporary relief rather than long-term investments addressing root causes starts with Harrell’s signature move this budget cycle: bridging the deficit by using $287 million in JumpStart or Payroll Expense Tax funds that had been originally earmarked by the city council to fund affordable housing, Green New Deal, small business supports, and Equitable Development Initiative. While Harrell maintains the outdated investment levels planned in 2020 for these categories – unadjusted for revenue coming in higher than expected and the high inflation rate experienced since that time – he is moving the rest to the General Fund to pay for everything else.

Diverting JumpStart affordable housing funds meant that Harrell had an additional $36 million to use above the projected deficit, but he still opted to cut 159 city positions, which will require laying off 76 employees. He has also cut many services in addition to the JumpStart funding priorities, including food and meal programs, public health programs, programs addressing gender-based violence, and community safety programs.

The result is the swelling of the Seattle Police Department’s (SPD’s) budget while upstream solutions like housing and food access and alternatives like the Let Everyone Advance with Dignity (LEAD) diversion program remain underfunded in the maintenance of the status quo.

How the Seattle Police Department fares in the proposed budget

In contrast, SPD’s budget is increasing by 16% or $62 million, contracts with the King County Jail and the SCORE jail are both increasing, and the Unified Care Team is receiving almost a $3.2 million increase so it can begin conducting encampment sweeps on the weekends as well as during the week.

The new Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG) contract is responsible for the bulk of SPD’s higher price tag, costing $47 million.

Many of SPD’s other increased expenses involve technology, including investments in real time crime software and closed circuit television systems, scheduling and timekeeping software, and the expansion of automated school zone cameras. The city is planning to continue its program of officer hiring bonuses, including $50,000 bonuses for lateral hires, an increase from the $30,000 bonus offered earlier this year.

SPD is also adding many civilian positions to supplement their inability to hire new officers. They are planning to hire 12 Real Time Crime Center analysts for 2025 with an additional nine to come on board in 2026. These analysts would relay pertinent information from the crime center to officers in the field.

SPD would also like to add seven civilian investigation support positions in 2025 with an additional seven added in 2026. Interim SPD Chief Sue Rahr said they are planning to bring back “retired detectives who know the processes” for these positions.

SPD emphasis patrols will be receiving a $10 million boost in 2025. This is in addition to their 2024 budget of a whopping $54 million for overtime. SPD’s overtime budget was only $37 million in 2023. In addition to pay increases negotiated in the SPOG contract, this number was inflated due to a 2023 memorandum of understanding with SPOG that gave officers higher event overtime rates in return for allowing Seattle to develop an alternative emergency response program.

That program, Community Assisted Response and Engagement (CARE), will be receiving an additional $1.5 million in funds, with more to come in 2026. However, this pales in comparison to the increase SPD is receiving, and in 2025 CARE’s responder program will cost less than 1% of SPD’s total budget for the year. CARE Chief Amy Barden (formerly Smith) said at the department presentation to city council that she expects the responder team to eventually save the city at least $1.1 million.

In addition, CARE continues to struggle under the city’s current memorandum of understanding with the Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG) in terms of how the team is allowed to deliver its services. Barden said the city has been in active conversation with labor about this issue.

However, city councilmembers seemed more preoccupied that the budget doesn’t call for any additional 911 dispatcher positions. Barden repeatedly explained there are currently 18 open positions that must be filled before any new positions would need to be funded, but some councilmembers still appeared interested in pressing the issue.

Another large item in the budget is the city’s Judgement and Claims fund, which will be increasing by more than $4.2 million in 2025 and $8 million in 2026. In addition, the fund will receive a one-time sum of $14.1 million next year. The proposed budget reads, “A handful of extraordinary claims and lawsuits involving the City is expected to lead to high one-time expenses in 2025 and 2026.”

The Seattle Department of Transportation, one of the other city departments responsible for a high level of claims, will be paying $8.1 million into the Judgment and Claims fund as its annual contribution. Interestingly, SPD does not have a similar line item visible in the proposed budget to pay its share into the fund.

Less money for addressing root causes

While SPD and the Unified Care Team are both winners in Harrell’s budget, some programs aren’t so lucky. Investments proposed for cuts include:

- Nearly $1 million for food and meal programs.

- $2 million from the LEAD and CoLEAD diversion programs.

- $200,000 for pre-filing diversion.

- $100,000 for survivors of police violence.

- $450,000 for programs addressing gender-based violence.

- $800,000 for public health programs providing behavioral health services for the Latino community and comprehensive substance use disorder treatment.

- $123,000 for legal counsel for youth and children

- $527,000 less rental assistance for tenants.

Critics are also decrying what they’re saying is a significant cut to funding to create more affordable housing in the city. Affordable housing has been shown to reduce crime, and having stable housing is a key component in reaching stability for people suffering from substance use disorder (SUD) and behavioral health disorders.

The Housing Development Consortium of Seattle-King County is one organization who is concerned about continued investments in affordable housing. In an email to the Mayor’s Office, Jesse Simpson, who is the group’s director of government relations and policy (and also a boardmember at The Urbanist), had a few requests related to the budget, one of which was to “retain the JumpStart spending plan allocation and avoid permanently rolling Payroll Expense Tax revenues into the General Fund.”

While King County’s unhoused population continues to grow, increasing by 23% since 2022, Harrell’s budget proposal doesn’t include funding additional non-congregate shelter spaces. Instead it merely maintains the current level of beds. The mayor is also slashing tenant assistance and eviction prevention services.

One area where there will be increased investment is in treatment for substance use disorder, where the city will be investing $14.5 million in 2025. More than half of that will be going towards the new ORCA Center, a post-overdose stabilization center planned to open in the first quarter of next year.

However, given the dearth of substance use disorder treatment capacity available in the area, it seems unlikely this investment will be sufficient to meet demand. As Cascade PBS reported last year, there is often a waitlist for both outpatient and inpatient treatment, which can lead to missing a person’s “window of willingness” to say yes to treatment.

And in her presentation on CARE, Barden said, “My team is uniquely poised in the city to be able to talk people into “Would you like detox?” They’re more successful than any other team right now at getting that yes. But what is awful is the days where we then call detox and it’s not available.”

In August, Harrell announced an investment to add 13 inpatient treatment beds at Valley Cities Recovery Place Seattle. At that time, Daniel Malone, the executive director at the Downtown Emergency Service Center (DESC), said, “Short-term beds for people who need to stabilize from substance use disorder remain in high need in our community.”

Meanwhile, there are only 11 detox beds available statewide for youth under 18 years old.

Diversion is another area where the proposed budget appears to underinvest. When the city council passed the law last fall that criminalized public drug use and simple possession, they said diversion was preferred to arrest in most cases. City councilmembers echoed this same preference for diversion during the discussion of the reinstated prostitution loitering law this summer.

However, since last fall, LEAD, one of the main diversion programs operating in Seattle, has been struggling to handle the increase in caseloads. It has had to move away from accepting community referrals that don’t require arrest in order to focus on those who have been arrested. Unfortunately, arrest – and the jail time that sometimes accompanies it – has not been shown to reliably treat substance use disorder. Jail time does, however, lead to an increased risk of overdose. While LEAD has received state and federal funding this year, the uncertainty of its funding streams means the organization is less able to engage in longer-term strategic planning or accept as many community referrals.

The proposed budget does include $2 million for survivors of commercial sexual exploitation, about half of which will go to forming a new city unit of victim advocates with a small budget to address the basic needs of their clients. That leaves $1 million for community organizations, which given the lack of services currently available for sex workers, could well be insufficient to address the increased need caused by the new law. For example, $1 million would probably only be enough to fund 10 to 11 beds at an emergency receiving center.

Election strategy at play

What this proposed budget does accomplish is a little something for everybody, an approach that shouldn’t be a surprise given the mayoral election in Seattle next fall. By not proposing additional progressive revenue sources, Harrell keeps his big business backers happy, and by reallocating the JumpStart tax to fill in the gaps, he avoids a major fiscal disaster for the city, while scrounging up enough to fund a big jump in SPD’s budget and his sweeps team.

While this may be a safe strategy for next year’s reelection campaign, the budget proposal may turn out to be short-sighted when it comes to addressing longer-term issues. A continued failure to address the city’s housing shortage and fentanyl crisis in meaningful and evidence-based ways means little relief in sight for those who are struggling, whether that be from poverty, from being unhoused, or from suffering from addiction or behavioral health challenges.

The strong showing of progressive challenger Alexis Mercedes Rinck and lackluster result for centrist Council incumbent appointee Tanya Woo in the August primary could signal that the Seattle electorate have quickly tired of a centrist ruling majority that is big on promises, but light on follow through and delivering durable and holistic solutions.

Following the 2020 George Floyd protests, city leaders have repeatedly said they want to lead with compassion, following evidence-based strategies and addressing racial disparities that stretch back to before our country’s founding. But with SPD being the major winner in terms of increased funding while upstream interventions and alternatives continue to be stymied and underfunded, this proposed budget is simply more business as usual for the City of Seattle.

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.