Seattle service workers are set to get a pay hike, unless restaurant lobbyists get their way. Policymakers can boost the restaurant industry in better ways than pay cuts

Last month, The Seattle Times organized a Town Hall panel discussion with four local restaurateurs, posing the question: “Why are Seattle restaurants so expensive?” The context, of course, was the hefty raise many restaurant workers are poised to see at the end of this year — so long as efforts to halt the final phase-in of Seattle’s minimum wage law don’t succeed.

If the event was an attempt to sway Seattle’s worker-friendly public by appealing to our self-interest as customers, it wasn’t terribly successful. The moderator, Jackie Varriano of The Seattle Times, gave her panelists multiple opportunities to complain about the upcoming wage hike. But, whether due to genuine support or fear of consequences (Cherry Street Coffee, anyone?), they didn’t take the bait.

However, their discussion did shine light on how January’s minimum wage increase might play out in the restaurant industry, other factors contributing to high prices and challenging times for Seattle restaurants, and what policymakers could do to help. It’s a meaty subject, so let’s dig in. (Sorry! No more food puns, I promise.)

How much will prices rise?

Seattle’s minimum wage this year is $19.97, but workers who receive tips or medical benefits at businesses with fewer than 500 employees are still making as little as $17.25 as their base wage. Just last week the City announced that in 2025, the minimum wage will rise to $20.76. That means a worker who now makes $17.25 an hour will get a raise of $3.51, or a smidge over 20%.

However, that doesn’t mean that restaurant prices will rise by 20%. We can do some back-of-the-napkin math to estimate how much more your $15 burger and fries might cost if the local brew pub passes all of that wage hike on to you, the customer.

First of all, a 20% increase in the minimum wage doesn’t mean that a restaurant’s total labor costs will increase by that amount. Only the workers now making $17.25 will definitely get this raise. According to one study, about a third of restaurant workers are paid close to the minimum wage. Of course, restaurants may find themselves also needing to adjust their pay scales for higher-paid hourly workers and managerial staff, but these increases won’t be of the same magnitude. So let’s estimate that total labor costs will rise by 15%, not 20%.

Second, labor costs are only one element determining the cost of your meal. The cost of the ingredients, rent, utilities, insurance also figure in. Restaurant industry common wisdom says that a good labor cost percentage is around 30% of gross revenue. At the Town Hall forum, Kristi Brown of Communion shared that her 2024 budget is consistent with this figure; her fellow panelist Ethan Stowell said that for some Seattle restaurants it’s getting up toward half. So for our purposes, let’s say 40%.

That means $6 of your $15 menu price is paying for staff wages and salaries, payroll taxes, benefits, etc. If those labor costs increase by 15%, the total cost of your meal will rise by 6% or $0.90. Round up for fun, and your $15 burger and fries becomes a $16 burger and fries.

This guess may be on the high end. A 2018 paper examining the price effects of San Jose’s 25% minimum wage increase that took place in 2013 found that prices rose by an average of 1.45%. And a hot-off-the-press paper on California’s sectoral wage policy for fast-food workers found that the new $20 wage floor that went into effect this year increased average hourly pay by 18% and, in addition to not reducing employment, increased prices by only about 3.7%.

So yes, high wages do contribute to high restaurant prices, and a large minimum wage increase will raise prices further, though maybe not as much as you’d suspect. The reality will be different for different restaurants. The Town Hall panelists spent some time discussing whether more restaurants might respond to the pressure by adding “service charges” — as an alternative to raising menu prices, or as part of a shift away from tipping altogether. I’ll come back to that later.

How can policymakers address cost drivers for restaurants?

Labor costs aren’t the only thing making restaurants expensive. The Town Hall panelists made clear that pretty much everything you can think of costs a lot these days: Licenses and permits. Initial investments in equipment and building out a space – generally paid by loans that become debt. Service and repairs to that equipment. Rent, utilities, and “triple net” – a share of a building’s property taxes, insurance, and maintenance costs, which panelist Ethan Stowell explained has been rising astronomically. Food ingredients. Broken windows and break-ins.

Can the City do anything about these costs? It could certainly review the official hoops a restaurant has to jump through to start up business or add a patio, and try to lessen the pain. It could extend and expand the expiring storefront repair fund that was put in place during the pandemic. And it could explore commercial rent control, which, unlike residential rent control, is not prohibited by state law; perhaps there are creative ways of regulating commercial leases, including the dreaded triple net, to make the overhead less onerous for restaurants and other small businesses.

In the question-and-answer session following the panel, restaurant worker and organizer Sean Case pitched a couple of ideas that would help both the restaurant industry and its workforce. Better late night transit service, he suggested, could improve access to bars and restaurants for customers and workers. I followed up to ask about his other idea in more detail:

“If City Hall and the restaurant lobby want to help struggling restaurants, there are myriad ways they can do so without punishing low-wage workers,” Case said. “One idea that would excite me as one of those workers is a publicly-run, portable benefits plan for workers at small businesses. Such a program could help attract and retain workers in a sector of the economy plagued by high turnover. By contributing to a public retirement fund for low-wage workers, small businesses could compete with larger companies who offer decent benefits while saving on the cost of operating their own retirement plans.”

The panel discussion touched on one more reason prices are high: customer counts are lackluster, with consumer confidence still depressed compared to the halcyon pre-pandemic days. But customer counts aren’t just about macroeconomic conditions. They also reflect the built environment. There’s a reason you can still get a slice of pizza in Manhattan for $1.50: it’s one of the most densely populated areas in the world. When a restaurant has a steady stream of customers all day, it can use its space and labor far more efficiently – and charge less.

Here in relatively sparsely-peopled Seattle, many establishments seem to have decided it’s not worth their while being open most of the time. Cafés close in the early afternoon. Restaurants don’t open till early evening. Nothing is open on Mondays. But density affects more than just hours and prices. University of Washington economist Jacob Vigdor sent me some data:

“King County has one food or drink establishment for every 443 residents; Spokane County has less than a quarter the population and supports one food or drink establishment for every 636 residents,” Vigdor wrote. “For New York City I could only find data for 2019, but at that point there was one establishment for every 353 residents.”

Think for a moment about what this means. It’s not just that one more person in a neighborhood equals one more customer; more density means more restaurants per capita. This suggests that people who live in dense areas go out to eat more often, perhaps because there are more enticing and convenient options nearby. Density seems to create a powerful virtuous circle for restaurants.

That points to another set of policy tools. Zoning reforms that encourage dense, mixed-use neighborhoods would spawn more locations where restaurants can thrive. And figuring out how to make office-to-residential conversions happen downtown would add customers to a neighborhood that, it’s now obvious, has been far too dependent on the nine-to-five office set.

Building a ton more housing – both market rate and subsidized affordable housing aimed at lower-wage workers – could eventually help in another way, too. By slowing the upward march of rents and housing costs, it would dampen regional inflation and thereby slow the increase in the minimum wage, which is tied to the Seattle-area consumer price index.

Why not give restaurants a break from higher wages?

Fine, you say. These solutions are all well and good, but most of them will take time. Stopping the minimum wage hike is something the City can do right now to stop the bleeding. But here’s the bottom line: shortchanging workers is not an acceptable answer to this problem. Let’s talk about why.

The Seattle Restaurant Association and others pushing to freeze the two-tier wage scale have made a big deal about inflation. When Seattle’s minimum wage compromise was negotiated, inflation over the 10-year phase-in was assumed at 2.4%. In that case, the lower tier would have merged with the higher tier at a universal wage of $18.13 an hour in 2025, which for most restaurants would have meant a manageable bump of $0.88 up from $17.25. No one could have predicted the sky-high inflation of the past few years, leading to a gap four times that large.

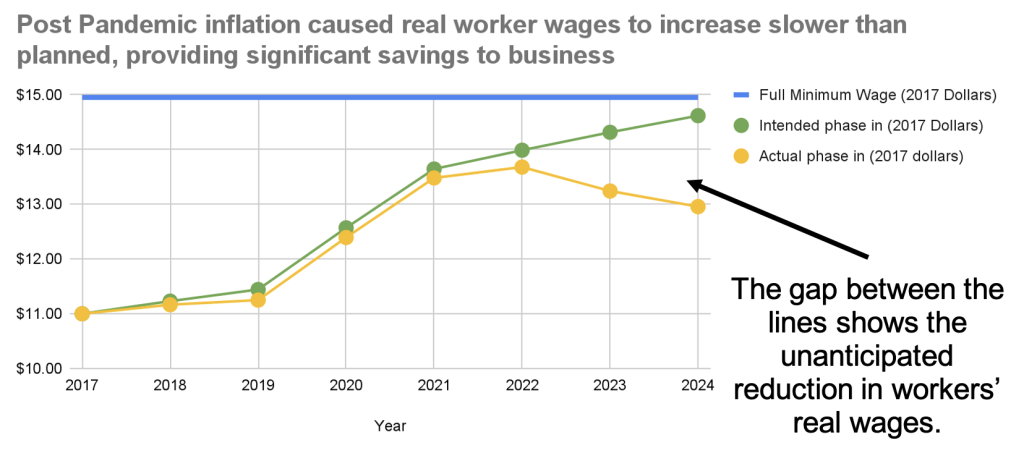

But there’s another way to look at this jump: It’s the result of lower-tier minimum wage workers getting the shaft over those same years, as the fixed raises of the phase-in fell far short of their rising costs of living. In fact, real wages for minimum-wage restaurant workers have been falling.

The promise and intent of the original minimum wage ordinance was to ultimately get everyone up to $15 an hour, measured in inflation-adjusted 2017 dollars. In 2022, the lower-tier minimum wage amounted to $13.68 in 2017 dollars. But this year, it’s back down to $12.96. If the Seattle Restaurant Alliance gets its way, most Seattle restaurant workers will never reach $15 an hour in 2017 dollars; they’ll be stuck forever at less than $13.

Put another way: inflation has depressed real wages for restaurant workers far below what was anticipated in the original minimum wage phase-in plan. This year, a full-time worker’s wages — and their employer’s labor costs — are about $4,600 lower than they should be.

But tips, you say! The other half of the argument is that these workers are doing just fine, because they make a ton of money in tips on top of their base wage. Why quibble over a few bucks an hour from the boss when the real money is flowing in from generous customers?

First of all, there’s the principle of the thing: tips are supposed to be a gratuity to workers, not a subsidy for their bosses. But that aside, it’s simply not true that all or even most restaurant workers are making the big bucks.

According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the median hourly wage (including tips) for waiters and waitresses in the Seattle Metropolitan Area is $27 an hour. MIT’s Living Wage Calculator estimates that a living wage in King County for a full-time worker with no kids or dependents is just over $30 an hour. Of course, waitstaff often don’t get 40 hours a week. But still, this means that after next year’s $3.51 raise, some Seattle restaurant workers could be making something approaching a living wage. That’s cause for celebration, not a reason to lower their pay. After all, we’re talking about living, not luxury.

This median also obscures a wide range. Some waitstaff at fine dining establishments are making bank — good for them. Others definitely aren’t, and they won’t be making a living wage even after next year’s wage bump. And tips are often unpredictable from one day to the next.

“What happens when a worker’s boss gets mad at them and they’re moved from a lucrative Friday night shift to a Tuesday afternoon?” says Sylvia Allegretto, Senior Economist at the Center for Economic & Policy Research and one of the country’s foremost experts on the tipped minimum wage. “Most of us would never think it’s reasonable that we go to work and the time we’re working is completely determining our pay, with a volatility that can be wildly different.”

Looking beyond the restaurant industry, waitstaff at full-service restaurants are among the better-compensated tipped workers out there. How about the person who makes your latte, cleans your hotel room, carries your luggage, does your nails, grooms your dog? All of these people deserve to earn a living wage.

A permanent subminimum wage for tipped workers could incentivize even more employers and industries to shift toward a tip-based model. If you, like Danny Westneat, feel that Seattle tipping culture is already out of control, you should be very worried. With those little Square registers proliferating madly, it’s only a matter of time before you’re being asked to add $2 to your purchase at the hardware store, the pet store, the 7-Eleven.

An end of tips?

Instead, we should be moving in the other direction. It’s hard to look squarely at the institution of tipping without coming to the conclusion that the whole system is deeply flawed.

There’s the racist history and the continuing racial inequity. There’s the sexual harassment. There’s the fact that the federal tipped minimum wage is still a mind-blowing $2.13 an hour, as it’s been since 1991 – before most of today’s restaurant workers were born. And there’s the different unspoken rules for different industries that befuddle Americans, let alone visitors from other countries. Can’t we just stop?

“All around the world, nobody does this,” says Allegretto. “And there’s a vibrant restaurant industry all around the world. When you do have tipping, as in France, it’s usually just a small token. You don’t have to tip.”

Town Hall panelist Ethan Stowell suggested that the upcoming wage increase might prompt more restaurants to add a mandatory “service charge,” paying their workers a much higher wage and adopting a no-tips or tips-truly-optional model. Stowell’s restaurant group recently made this shift, because it grew to exceed the 500-employee threshold and thus ceased to be eligible for the lower-tier minimum wage.

I know, I know, I hate service charges too. Arguably they’re a “junk fee,” something I’ve railed against in other areas of the economy. But listening to the panel discussion gave me a new appreciation of the challenges facing restaurants that want to move away from tips. Unless everyone’s doing it, raising menu prices enough to pay your staff a truly decent wage makes you look way more expensive than the competition. Stowell pitched service charges as a possible intermediate step toward the “Euro model” of all-in pricing.

Ditching tips isn’t universally popular with employees, which makes sense given how variable tipped workers’ income can be. But it does come with some big benefits. Less tension between front-of-house and back-of-house workers. Higher vacation and sick pay rates, since these are generally calculated on a worker’s base wage, not including tips. And another that Stowell mentioned: If a worker is (gulp) trying to buy a home, getting a loan is a lot easier if you can demonstrate stable income.

I’m not holding my breath for an end to tipping. But that’s not the reason we’re doing this, anyway. More and more new research is showing that minimum wage increases result in workers getting paid more – as you’d expect – and they don’t kill jobs, even in small businesses. In fact, they actually create jobs.

So even if some restaurants struggle next year, others will thrive. The industry will adjust and workers will come out ahead. Remember that when you hear reports that the sky is falling. And if restaurants respond to the pain by taking steps toward a tipless future, I’m all in. After all, you can’t make an omelet without breaking some eggs.

This piece is part of Katie Wilson’s ongoing Policy Lab series. Check out the introduction and earlier installments, which have covered mode shift incentives, taxing the rich, paid vacation, and more.

Katie Wilson is General Secretary of the Transit Riders Union, a Seattle-based organization advocating for improving transit quality and making access more equitable.