Filmmakers seeks an antidote for placelessness; Wallingford can help by being a place more people are welcome.

Sometimes the whole really is greater than the sum of its parts. I found this to be true in spades for “Seattle of the Future? Closing Shorts,” Northwest Film Forum’s curation of three films intended to spur a thought-provoking conversation about what Seattle we want for the future. The festival ran through September 29.

For me personally, it’s fair to say that my experience hit close to home, as the longest of the three is about the neighborhood I’ve lived in for the last 20 years, Wallingford. (I’ve written about it here, and even make an appearance as a participant in one of the walking tours conducted during its filming.)

But even as someone previously familiar with that project, viewing it in this context gave me a fresh perspective on how to wrestle with a question posed by the Northwest Film Forum: “how do we provide an antidote to ‘placelessness?’”

Here’s why.

I admit I was primed for disappointment with “The Beacon,” a short film about the break-dancing studio founded by Seattle hip-hop b-boy crew, Massive Monkees.

By that, I don’t at all mean disappointment with the film’s quality. Instead, because its producer, Vanishing Seattle, describes itself as “a media movement that documents displaced and disappearing institutions, small businesses, and cultures of Seattle” I was expecting something along the lines of “a tragic story, with a sad ending.”

But then I found myself delighted by learning about the group’s passion, resilience, and (in the end) success.

The specific phrase “emerging Seattle” came to mind while watching it. It was literally a story about something new under the sun coming into being here (beginning with after school programs at the Jefferson Community Center in the 1990s), taking enduring root in the community, and (with a two year interruption between 2020 and 2022) also finding a physical location through which to serve its mission.

And this gave me the gift of seeing “Visions of Wallingford” in a new light.

On one of the project’s walking tours, another Wallingford resident described “placelessness” this way: “Placelessness, according to Oxford, is a condition of [an] environment lacking significant places and [an] associated attitude of lack of attachment to a place caused by the homogenizing effects of modernity.”

I know it is something many of our respective neighbors are concerned about either consciously or unconsciously. And the film highlights “anti-placeleness” activism large and small. (In the case of the former, for example, preventing the Good Shepherd Center property from being turned into a shopping mall in the 1970s. In the case of the latter, community volunteers placing a bench in a traffic circle and then decorating it with handcrafted, bespoke tiling.)

But I don’t think the Oxford definition of placelessness is our neighborhood’s biggest problem.

Instead I think it is that what becomes the next “Beacon” has no place to emerge here. And that’s because the people who will bring into being the next movement or innovation that differs from the dominant culture–the people who are “poorer, browner, younger, and more diverse” largely have no place here.

Why did the hip hop community take root in the South End? Because that’s where Seattle’s White majority chose where they wanted Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) and poorer people to live.

Why didn’t the first hub for that community emerge at the Good Shepherd Center? Because Wallingford’s White majority didn’t care to create places for those communities to live here.

If you think that’s an exaggeration, let’s briefly set the record straight.

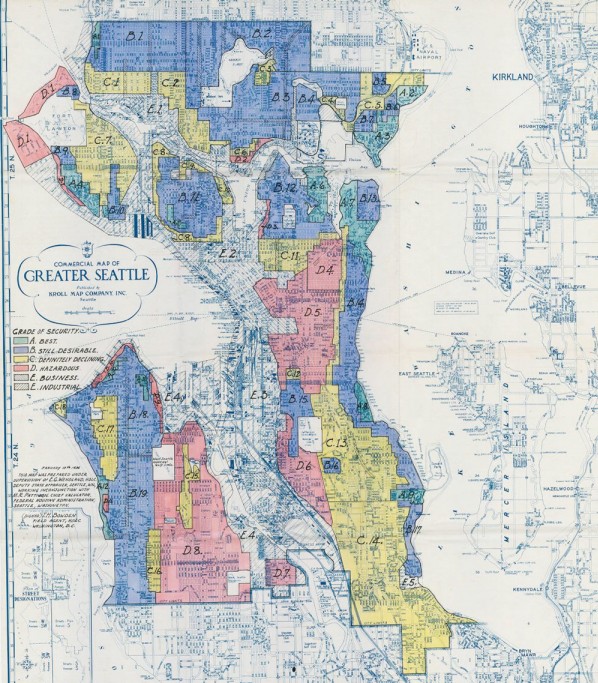

North Seattle (Wallingford included) was a “sundown” zone until the late 1960s (that is, “virtually no people of color lived” and “that African Americans were expected to be out of the area when the workday ended”). Wallingford was both redlined and largely zoned for single family homes by the Seattle’s avowedly racist 1923 zoning commission (as the City acknowledged in page 19 in the housing appendix of the draft One Seattle Comp Plan).

More recently, the neighborhood’s community council fought creation of more affordable homes here in the 1970s–getting “places students and laborers could afford” banned by law. And in the 1990s neighborhood planning process, the community’s answer to the question of whether “zoning changes to accommodate a greater variety of housing types in the community, and to support home ownership at lower levels of income” should be made was largely “no.”

It’s damning with faint praise that the concession to diversity and inclusion enshrined in the neighborhood plan – new housing along Aurora, I-5, and by the Fremont industrial area – was indistinguishable from the intentionally environmentally racist planning decisions from the 1920s and 1950s. (This is something the City has documented and is explained in the context of the current comprehensive plan update in a 20-minute video, “Harland to Harrell.”)

The upshot is that, as one elder community member stated in the film: “Wallingford is a wealthy, White, older neighborhood. And I think we ought to acknowledge the very Whiteness of it…”

Now, more than ever, I believe she’s right.

One of the goals of the “Visions of Wallingford” project was to “reframe challenging conversations” about our changing physical environment. I’ve been in my share of challenging conversations about housing and land use and city planning both online and in-person at community events and city forums over the past decade.

But even as someone who has devoted a lot of time and attention to these issues, after viewing this trio of films together I’ll readily admit I may have missed the forest for the trees. A lot of words and ink has been devoted to debating how many parking spaces apartment buildings should have, or whether adding accessory dwelling units should come with an owner occupancy requirement, or on which blocks townhomes should be legalized.

So let me suggest starting again with some different questions:

We’re a very White neighborhood.

Do we want to change that?

Are we willing to try?

Today from where I sit, the jury remains out, and our track record is not good.

But now, after watching “Seattle of the Future? Closing Shorts,” when I think about “how we would like to see Wallingford in the next 50 years” I have a new short answer. The next equivalent to that Jefferson Community Center afterschool program that evolved into a community and eventually The Beacon ought to be able to happen here.

In the meantime, The Beacon is open for business on Rainier Avenue S and accepts donations.

Bryan Kirschner

Bryan Kirschner works in technology and lives in Wallingford.