One of the highest affordability mandates in the region could actually serve to stifle development near light rail.

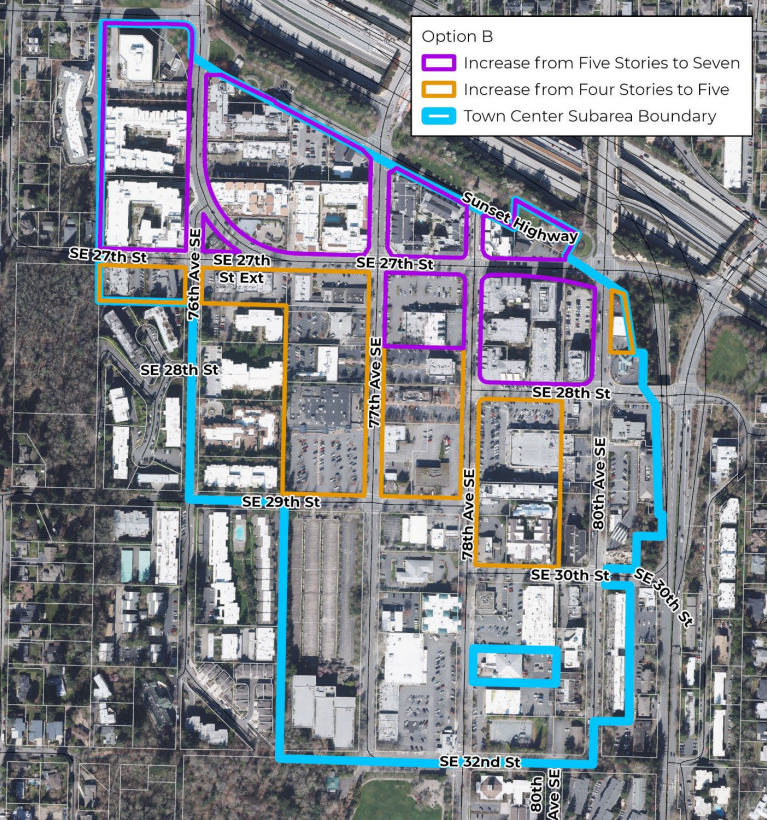

The Mercer Island City Council unanimously approved a motion this week to modestly expand housing capacity in its Town Center neighborhood south of I-90, close to Sound Transit’s 2 Line light rail station, set to open in late 2025 or early 2026. Under the proposal, properties on the north end of the neighborhood, close to the freeway, would be able to rise to seven stories compared to the five-floor height limit today, and properties further south would be able to rise to five stories.

At the same time, the Council also approved a directive to increase restrictions on developers that could result in even less housing built in Town Center in the coming years. A high housing affordability requirement on new housing may sound helpful in theory, but if it deems construction financially infeasible, no new housing would result, affordable or otherwise. That would be par for the course since Town Center hasn’t seen a new building permitted since 2014.

The impetus for Mercer Island’s proposal isn’t necessarily a desire to create more housing opportunities close to regional transit investments, but rather to comply with state law, namely the housing requirements in House Bill 1220. HB 1220 is a 2021 law that updated the state’s Growth Management Act to require cities to align anticipated future housing needs with the expected income levels of future residents, and rezone accordingly.

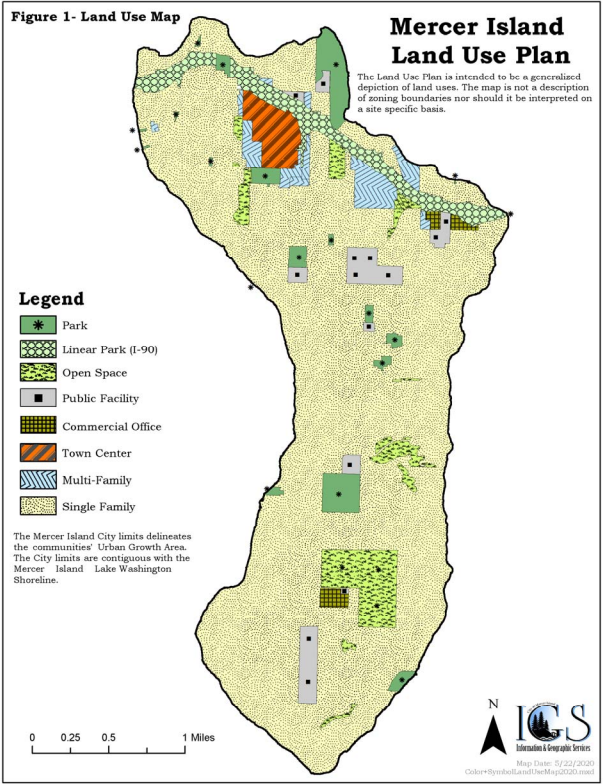

With lower-income residents priced out of detached single-family or even missing middle housing types, such as backyard cottages or duplexes, only the option to construct multifamily housing aligns with those expected residents. The average Mercer Island single family home is valued at $2.3 million, according to Zillow estimates.

Across the state, cities large and small are grappling with how to implement HB 1220, as it represents a brand new way to look at local housing growth targets. It doesn’t allow municipalities to plan for growth using capacity that exists on paper but remains highly unlikely to result in housing that’s affordable to most Puget Sound residents. In Mercer Island, the law has resulted in significant frustration given an across-the-board reluctance to look at rezoning lower density residential areas, including those just as close to light rail as some areas of Town Center.

The 20-year housing target that Mercer Island has to incorporate into the update of its Comprehensive Plan, due by the end of 2024, is 1,239 dwelling units. While the city as a whole has capacity to add over 1,400 homes without any zoning changes, much of that capacity exists in its single-family zones, which make up 83.4% of Mercer Island’s residential land. And of those 1,239 homes that the city needs to plan for, nearly 60% are expected to house people making 50% of King County’s area median income or below — around $74,000 per year.

Guidance from the state’s Department of Commerce has been to correlate affordability levels with density, with the bottom line being that the city needs to create more multifamily capacity — at least 143 units in Mercer Island’s case.

Earlier this year, the city briefly explored the idea of creating new multifamily housing capacity in south Mercer Island, near a commercial hub that includes a QFC grocery store. However, that proposal was met with vociferous opposition from Mercer Island residents, who inundated the city council with emails pushing back on the idea.

Council also explored whether to convert a commercial-only zone along I-90 but shied away from that as well. This week, they considered whether to upzone the entire Town Center area by one story — labelled option A — but ultimately picked option B that concentrates the new capacity near I-90, raising the upper height limit on several blocks to seven stories.

Mercer Island hasn’t exactly been in a rush to see its Town Center develop. In 2020, city council imposed a development moratorium on the southeast quadrant of the neighborhood, citing concerns around loss of retail space, and did not lift that moratorium until late into 2022.

The entire Town Center had also been under a moratorium from February 2015 to June 2016, which was in response to “Save Our Suburb” backlash against a mixed-use apartment proposal across from Metropolitan Market. That project is finally breaking ground a decade later under a different developer, albeit with fewer homes planned. Nonetheless, those 159 new apartments mark one of only a handful of new apartment buildings in a mostly lost decade for Town Center, leading up to light rail’s arrival.

The extra capacity Mercer Island is contemplating now could potentially add a few extra hundred homes near some of the fastest planned transit connections to both Seattle and the Eastside, but the council added a big caveat. Council also approved a motion that will lead to an increase in the mandated number of affordable units in new buildings, raising the requirement from 10% to 15%. Those 15% of units would have to be affordable to residents making 50% of the county’s area median income (AMI) or below — a requirement that would mean Mercer Island has one of the most stringent affordable housing mandates in the region.

While buildings two stories or less would remain exempt from that requirement, it would cover the entire Town Center area, even where height limits aren’t being increased.

Affordability mandates, through so-called “inclusionary zoning” programs, are becoming more popular around the country as a way to create subsidized affordable units without raising taxes more broadly. Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) requires a range of anywhere from 5% to 10.6%, depending on the specific parcel, with cities like Shoreline and Redmond having 10% baseline requirements. While some cities do have percentage requirements at 15% or above, those requirements are almost all paired with a higher income cap than the 50% of area median income that Mercer Island is proposing. In Seattle, the affordability requirements were tied to greater zoning capacity, offsetting their cost, at least partially.

For units being built to own and not rent, Mercer Island would require 15% of units be available to people making 80% of the area median income — or around $118,000 per year and below.

In Tuesday’s meeting, Mercer Island city staff were asked about the process to develop the 15% number. Jeff Thomas, Mercer Island’s Community Planning & Development Director, said that they had been in conversations with A Regional Coalition for Housing (ARCH), an organization that works to create affordable housing on the Eastside in partnership with a broad coalition of Eastside cities that contribute annual funding.

“What we found in having ARCH’s consultant work with Mercer Island here recently, is that […] even with interest rates where they’re at currently, in the process of falling it looks like, 15% does come pretty close to a standalone feasibility on a seven-story project on Mercer Island. With the lesser stories, so like going from the four to the five, that was also part of option B, [it’s] not quite there just yet, with interest rates, in terms of feasibility at the 15% level.”

Thomas added that additional strategies outlined in Mercer Island’s draft Comp Plan, like streamlined design review, lower parking requirements, or waived permit fees for affordable units, could go even further toward making projects pencil, but it’s not clear when exactly the city would get around to advancing those ideas.

Mercer Island Mayor Salim Nice touted the potential for outside funding sources to fill the gap when it comes to feasibility, focusing specifically on units-to-own.

“I have heard and had discussions with other mayors in the region that with subsidies and and funding through Microsoft and through Amazon’s housing funds, that there is development contemplated at 100%, 80% AMI units. And so there are going to be some things in the marketplace that are not free market principles, but do have other forces behind them that can help us get to the 80% AMI units.”

Not mentioned was city-provided funding: Mercer Island’s contributions to the ARCH housing trust fund in 2024 totaled just $76,611, or 0.2% of the City’s general fund budget.

Nice has been a familiar figure at state legislative hearings in recent years, often advocating against bills increasing minimum residential density like House Bill 2160, which would have required Mercer Island to permit larger apartment buildings within a quarter-mile of its light rail station. HB 2160 didn’t make it across the finish line in 2024, but if it had passed, Mercer Island likely wouldn’t have had any trouble complying with HB 1220 — an analysis conducted by the land use advocacy group Futurewise showing that compliance with the bill would unlock 25.5 million square feet of development capacity in Mercer Island, all of it outside the existing Town Center area where zoning already exceeds the baseline requirements of the bill.

Meanwhile, city leaders have hosted little discussion of building more housing to alleviate the region’s housing shortage and improve outcomes for working class residents. With Mercer Island’s primary consideration apparently a desire to appear compliant with state law, Nice was already focused on 2029, when King County cities are evaluated on their HB 1220 performance.

“At the five-year check in, being able to go in there with this kind of capacity and with these types of targets into our bonus incentives, I think it gives us good ground to say that we did try,” Nice said. “We’re not going to want to argue that we didn’t achieve our goals because there were points in time in the five-year period that we didn’t have the capacity that was required.”

While other regional leaders are focused on trying to move the needle when it comes to housing affordability and homelessness, Mercer Island leaders remain deadset on doing the bare minimum needed to comply with state housing law. That effort may find success under the current growth target framework, but may not survive additional changes in state law that could be coming down the pike.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.