Zoning has been used as an urban planning tool for thousands of years, if one considers the beginning of zoning to be the delegation of undesirable city functions beyond the ancient Roman city walls.

In its modern form, however, zoning is thought to have begun in Germany in the 1870s, though the American system diverged within a few decades. As Sonia Hirt, professor of landscape architecture and planning at Georgia University, and author of Zoned in the USA says, zoning in the United States had developed into an “autonomous” and separate system by the 1930s.

In many early cases, zoning was used to separate the functions of industrial, commercial, and residential living. In addition, it was often used as a tool to enforce class and racial separation. From the beginning, residential zoning tended to favor the building of single-family homes, which exacerbated racial and class divides, and in many cases prevented access to good school districts and healthy neighborhoods for those on the outside.

Approaches to zoning have changed significantly over the past 150 years, with zoning codes expanding inordinately, driven in part by “not in my backyard” (NIMBY) homeowner activism. In some places, opponents of NIMBYism, who sometimes call themselves YIMBYs, have won policy changes to redress the problematic effects zoning has had.

What is Zoning?

Zoning is a way of determining the use of land, or parameters of buildings in urban space. Zoning can be based around the function of a development, such as residential, commercial, or industrial. This use can be single-use or mixed-use. For instance, a mixed-use zone could include apartment buildings and low-impact commercial enterprises, such as restaurants, small shops, cafes, and public services such as hospitals and schools.

Zoning can also be based around form, such as a limit on the height of buildings, or a zone that requires a certain level of density. Other types of zoning may be based around the effects of a development, and how it will contribute to the existing area, or zoning based on incentives. One example of this could be a developer who is allowed to build an apartment block, but only if they include public housing, a community center, and a park as part of the development.

Opponents often refer to restrictive zoning as exclusionary zoning. For example, zoning for only single-family housing is exclusionary zoning, as it increases housing prices and may shut out lower-income families from the area (who could, for instance, afford an apartment, but not a single-family home).

On the other hand, inclusionary zoning intends to provide affordable housing as part of apartment developments and multi-family dwellings. In its mandatory form, inclusionary zoning requires that builders provide a set percentage of affordable housing. Set the percentage too high, and some housing advocates would argue inclusionary zoning has the opposite effect by making new housing infeasible to build. Inclusionary zoning may create more opportunities for nonprofit homebuilders.

The History of Zoning in the United States

Early zoning focused on separation of land uses, which was in some instances fine-tuned to separate industries within industrial zones. William Fischel, former professor of economics at Dartmouth College and author of Zoning Rules! says that many early zoning codes focused on separating land based on industry, such as keeping meat-packing districts distinct from clothing districts. In part, the intention was also to reduce congestion in cities, first keeping workers close to their own industries, and later, keeping residential areas free from large trucks and buses.

This continued until the late 1920s, when the Standardized State Zoning Enabling Act came into force, followed by the Standard City Planning Enabling Act. These two pieces of legislation provided a standard regulation that was intended for states to follow, and guided the development of zoning regulation over the next decades.

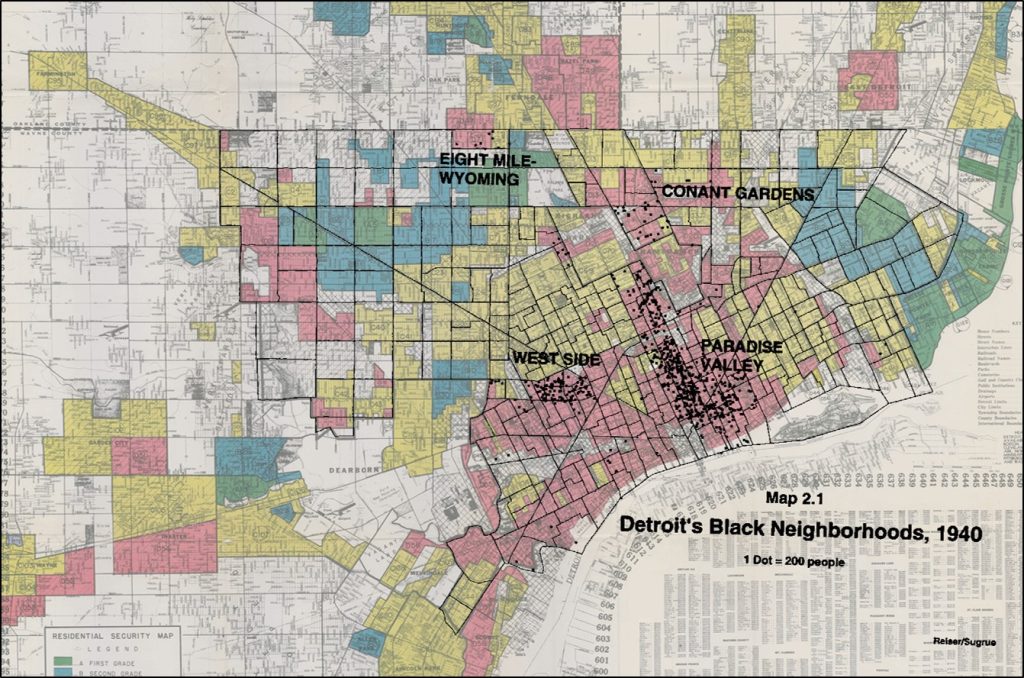

Alongside the more practical developments, many early zoning codes were also used in pursuit of racial and class segregation. In Buchanan, a famous case in 1917, a White man (Buchanan) had sold a house to Warley, a Black man. In Louisville, where they lived, an ordinance didn’t allow Black people to live on a block where the majority of existing residents were White, and vice versa. This type of ordinance was common throughout many Southern states at that time. The Buchanan case went to court, as Warley cited the ordinance as a reason why he couldn’t complete the purchase of the house. The court ultimately struck down the ordinance as unconstitutional.

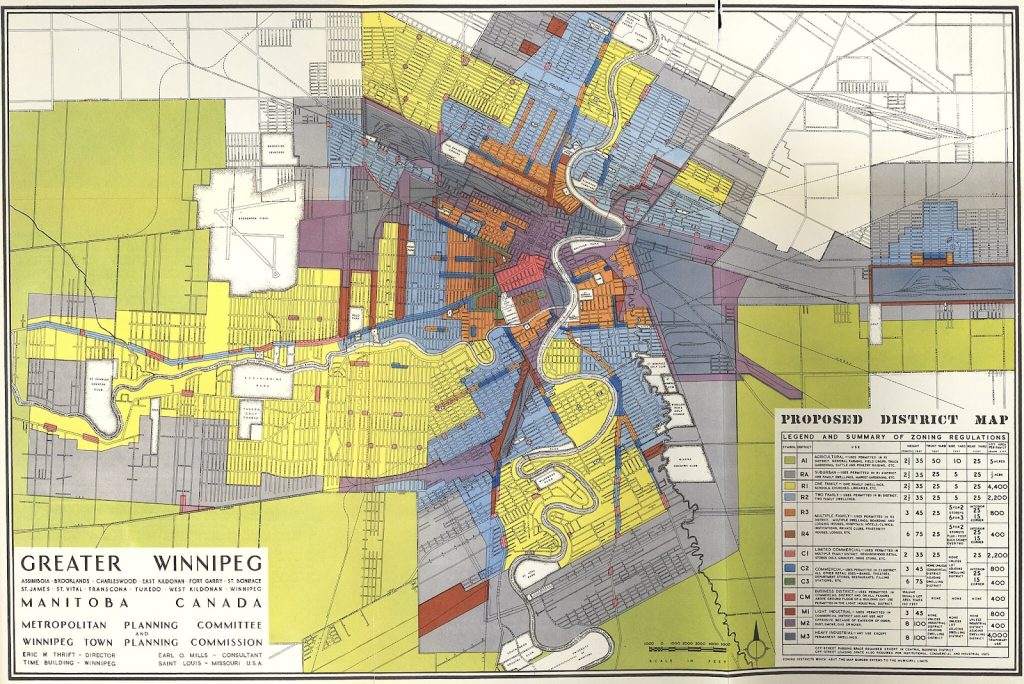

Despite this ruling against direct racial segregation, cities did not pursue integration, and instead post-Buchanan zoning codes became one of the primary means to enforce segregation. Unlike the struck-down ordinances, zoning does not explicitly mention race. Nonetheless, Harland Bartholomew, the Saint Louis urban planner who wrote or consulted on hundreds of zoning plans in cities across North America, admitted the intent of his zoning plans was to seek racial and economic segregation. “According to Bartholomew, a St. Louis zoning goal was to ‘preserv[e] the more desirable residential neighborhoods,’ and to prevent movement into ‘finer residential districts … by colored people,’” legal historian Richard Rothstein writes.

In 1919, Frederick Law Olmsted, a landscape architect and planner, stated in the 11th National Congress on City Planning that “apartment houses and multi-family houses should be assigned to specified districts, and single family houses should be in districts which have adequate protection against apartment houses.” This was to prevent the intermingling of people who lived in each type of dwelling, which typically aligned with class and race. According to Strong Towns, this was also considered to be a “moral” issue, with the character of the “American home” at stake, threatened by apartments.

At a high level, Fischel explains that zoning in the United States has had three main phases. At first, zoning was a tool that was very pro-developer. Developers were able to build relatively freely, without large amounts of pushback from homeowners or the public. Homes also retained relatively stable prices during this time.

In the second phase starting in the 1960s and 1970s NIMBYism arose much more strongly, coupled with the environmental movement. The NIMBY movement was characterized by community resistance to a large swathe of potential developments. The 1970s were also the time of the great inflation, with prices for houses rising rapidly.

Fischel also says that when people have such a large amount of money in one particular asset, they become protective of that asset. Unlike a diversified stock portfolio, a house is an extremely concentrated investment. The investment of homeowners in their properties led to increased political involvement (what Fischel calls the “Homevoter Hypothesis”) and an influence on zoning codes and how they were used. This investment of homeowners can have positive effects, such as preserving or improving the neighborhood in ways that are considered to be desirable, as this increases the property value.

However, the NIMBY movement also led to a resistance to any “undesirable” developments or encroachments on the neighborhood. This resistance included pushback against low-income housing, people from lower-socioeconomic groups, and racial discrimination, much like the segregationist policies of decades before. In a 1998 article, Raphaël Fischler explains that because “proximity to people of a lower social status diminished the market value of property, the stability of prices depended on the preservation of safe distances between socioeconomic racial groups.”

In the third phase, which is arising now, Fischel believes that the YIMBY movement has begun to shape the discourse around zoning and housing with “responsible communities, who realize ‘Uh oh, what were we thinking?’ … This sensible tool has gotten out of hand and is causing a lot of social problems.” Fishel says that the YIMBY movement is “emblematic” of larger societal shifts “… maybe it will be an important change.”

Zoning approaches are certainly in need of many adjustments. Samuel Stein, author of Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State, explains that zoning at this point has become a tool that is overused by cities, with the zoning code in New York City ballooning “from a hundred pages to several thousand.”

Stein explains that “we try to do more and more with zoning, because other means are less available. Zoning was not really supposed to be a tool of affordable housing production, for example, but because so many better ways of achieving affordability are off-limits to cities. This is either because the money isn’t there, or because there are preemptive laws that prevent them from doing things. So, they do it through zoning instead.”

Why Zoning Matters

So why does all of this matter? And are the old discriminatory approaches of zoning simply in the past?

Using zoning as a tool to govern land use has shaped the urban landscape in a number of ways, many of which have both positive and negative consequences. Separating functions of land provides increased health benefits (i.e. being further away from a large steel factory), but in the absence of good public transport access, can increase sprawl and a reliance on cars.

In addition, the single-family home is now culturally embedded in the idea of the American dream, which creates resistance to change. Sonia Hirt says that “there is a very deep American attachment that goes back to the time of William Penn, to the idea of living a private life.” The connection between single-family homes and the idea of a “private life” is clear.

Nonetheless, Hirt explains that when it comes to planning and zoning, we cannot blame the issue only on culture. It’s “more complicated than this,” she says. “I don’t think we can just blame it on the people and be angry about it.”

Richard Kahlenberg, author of Excluded, agrees, saying that the cultural connection to the single-family home is there. However, he notes, “No one is saying that people who own a single-family home have to change and have to build a duplex. It’s just that they can’t prevent all their neighbors, who might choose to do that, from doing so.”

Aside from finger-pointing games, it is clear that zoning matters: its use as a racial and class discrimination tool has had a large number of effects that cannot be described as “in the past”. Many effects are generational, with consequences that continue to ripple out. In addition, exclusionary zoning is still present today, with zoning for single-family homes still predominating. A New York Times report found that in many neighborhoods and cities across the US, around 85% of the urban space is zoned for single-family housing.

Interestingly, one study that examined the distribution of prohibitive zoning laws in California, found the most prohibitive zoning in areas that lean predominantly liberal. In addition, as noted by Kahlenberg in a piece written for The Atlantic in 2023, Jenny Schuetz’s work finds that “overly restrictive zoning is most prevalent and problematic along the West Coast and the Northeast corridor from Washington D.C. to Boston.” These areas — like most big U.S. cities — are predominantly run by Democrats.

Omar Wasow, an assistant professor of politics at Princeton University said in a CNN interview that “There are people in the town of Princeton who will have a Black Lives Matter sign on their front lawn and a sign saying ‘We love our Muslim neighbors,’ but oppose changing zoning policies that say you have to have an acre and a half per house”. Kahlenberg explains that some of this has less to do with issues of race, and rather discrimination based on class: as Fareed Zakaria puts it, “the great sin of the modern left is elitism.”

With housing prices prohibitively high in many places, and significant resistance to change even in apparently progressive communities, urbanists, communities, and city governments are all looking for answers.

Looking ahead to solutions

Zoning plays a complex role in the history of the United States, including as a vital aspect of enforcing racial and class segregation in many cities. It has also contributed to a swathe of single-family homes across the country, and prohibitively expensive housing for many people. The solutions to this issue have been somewhat elusive, although many are working on it. Some of the answers appear to be clear, but require consistent action at numerous governance levels.

In Part II of Zoning 101, we will take a look at solutions to the housing shortage that restrictive zoning policy has promoted. We’ll also go through a few examples of cities and how they are dealing with zoning issues.

Leah Hudson is an editor and writer published by Insider, Atlas Obscura, and Penguin Random House New Zealand. Leah loves to write about sustainable urban development, mental health, and matters of the heart. She spends her time reading, walking her dog, and eating unreasonable amounts of chocolate. You can find her at https://leahhudsonleva.com/.