On Tuesday, Seattle City Council’s public safety committee voted to authorize the purchase and installation of two new surveillance technologies in Seattle’s neighborhoods: a closed-circuit television system (CCTV) and real-time crime center (RTCC) software. As the issue moves to a full council vote on October 8, the city has taken another step closer to implementing Mayor Bruce Harrell’s technology-assisted crime prevention pilot.

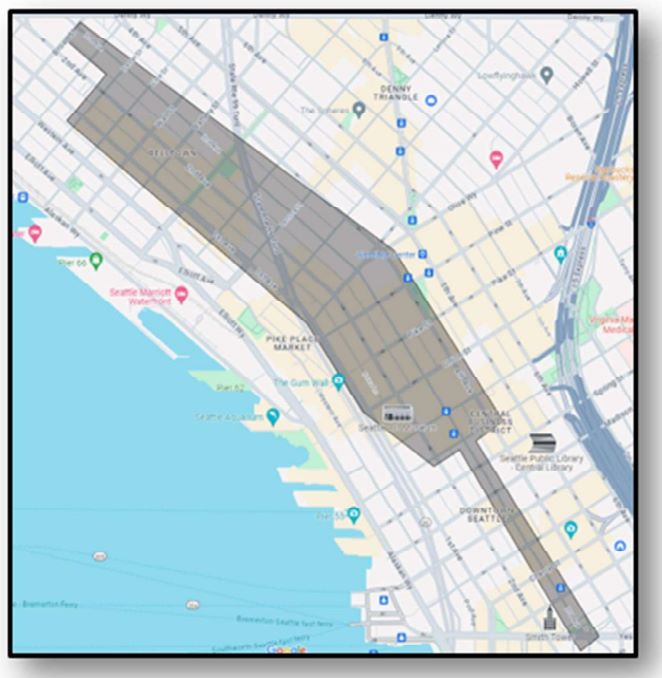

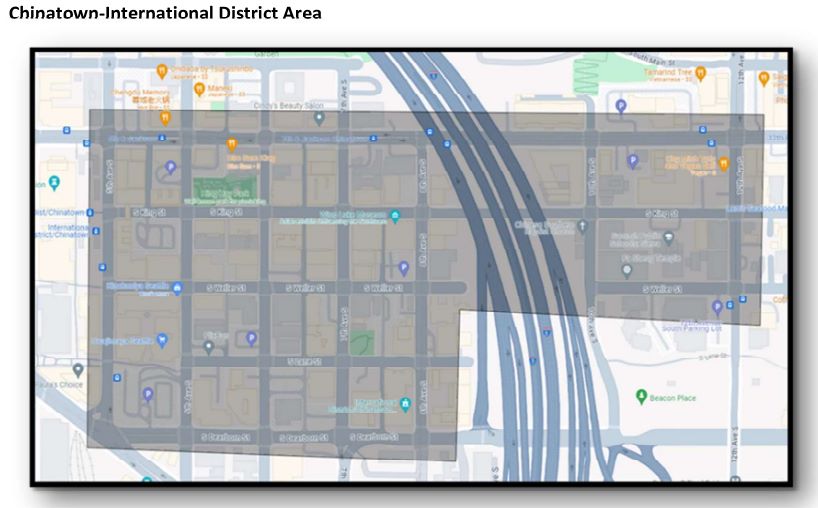

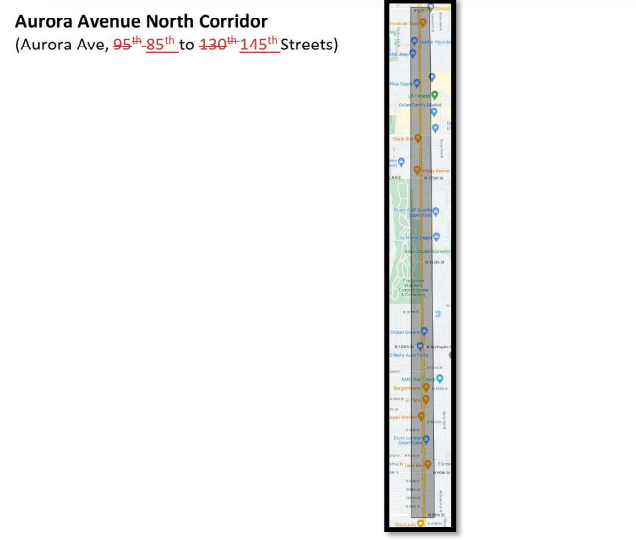

The three areas currently scheduled to receive CCTV cameras are the 3rd Street corridor downtown, Aurora Avenue in North Seattle, and the Chinatown-International District (CID).

Harrell’s proposed 2025 budget allocates almost $4 million for this pilot, with $1.5 million for CCTV cameras and $425,000 for new additional locations of CCTV, which might refer to Councilmember Cathy Moore’s amendment expanding the technology throughout the Stay Out of Area of Prostitution (SOAP) zone on Aurora. The proposed budget allocates $2 million for the RTCC software, which includes 12 new civilian analyst positions within the Seattle Police Department (SPD), meaning part of this cost will be ongoing.

Harrell’s plan adds another nine positions to the RTCC center in 2026.

The cost has ballooned from the budget ask for this pilot last year, which was $1.5 million and supposed to include the cost of Shotspotter acoustic gunshot location technology. The estimates for all three technologies within the pilot have changed repeatedly since that time.

However, Harrell dropped ShotSpotter from the package of surveillance technologies earlier this summer, citing cost. A large community outcry against Shotspotter, citing privacy and effectiveness concerns, as well as a myriad of other American cities recently dropping their own contracts, might have also impacted Harrell’s decision.

Chicago’s large contract for ShotSpotter ended this past weekend amidst contentious debate between its mayor and city council.

The Seattle City Council voted to approve a massive expansion of license plate readers earlier this year, waiving aside concerns about flaws in its data privacy plan. Previously, this technology was deployed in only 11 SPD squad cars, but now it will be in 360 SPD vehicles.

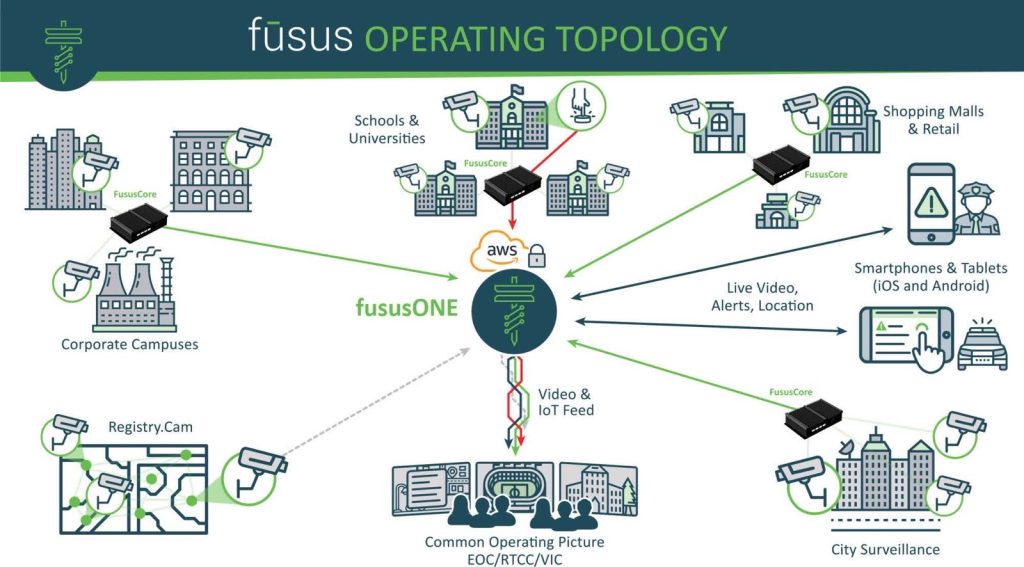

The city’s contract with Axon for this expansion has yet to be finalized. Councilmembers had a briefing with Axon about required contract language on Monday. The city will also be contracting with Axon for the CCTV and RTCC technologies.

A number of organizations have signed onto a letter opposing the pilot, including the ACLU of Washington, One America, 350 Seattle, Chief Seattle Club, El Centro de la Raza, the Gender Justice League, Massage Parlor Outreach Project, Planned Parenthood Alliance Advocates, and WA People’s Privacy.

One such organization is the CID Coalition, a grassroots organization who live, work, and have roots in the CID neighborhood. They have expressed their “ongoing opposition to increased surveillance in our neighborhood and Seattle at large” and a preference for evidence-based solutions that do not further discrimination.

“Within the CID community, pro-surveillance individuals are tokenized as representatives of the whole neighborhood when their views can be utilized as justification for increased policing,” a spokesperson for the CID Coalition told The Urbanist. “Safety concerns are weaponized and community members are promised false solutions like CCTV that are ineffective and dangerous to our community. Surveillance like CCTV is just another tool to criminalize, threaten, and disappear people in our community.”

“We are deeply concerned about the City’s efforts to deploy CCTV cameras and real-time crime center (RTCC) software despite evidence that these technologies do not reduce violent crime and disproportionately harm communities of color,” ACLU of Washington technology policy director Tee Sannon said. “Despite these serious risks, the proposals are being rushed without full consideration of the Community Surveillance Working Group’s and the public’s concerns.”

Civil liberties report finds major problems with pilot

In a letter to council, Harrell cited increased gun violence and low police staffing as reasons to implement the surveillance pilot. He said the city recorded more than 1,000 comments about the technologies, but he failed to offer a breakdown of how many of these comments were in support of the project.

However, the city’s Community Surveillance Working Group (CSWG) was tasked with completing a privacy and civil liberties report on the surveillance pilot, which sheds further light on the breakdown of public input. That report said: “The City received a substantial number of public comments, both in-person and submitted electronically, regarding the potential misuse of these technologies. These comments were overwhelmingly negative and voiced a serious concern and lack of trust within the community as a whole of the Seattle Police Department’s plan to expand the use of surveillance technology.”

All together, the report outlines 12 major issues of concern with the new pilot, including conflicts and impacts on basic constitutional rights, lack of clarity about several aspects of the technology and the pilot, and privacy risks.

During the public comment period of the first public safety meeting discussing this proposal, René Peters, the co-chair of the Community Surveillance Working Group, painted the surveillance expansion as not fully baked.

“Key issues include the impacts on constitutional rights, concern that the risk of disparate impacts on minority communities aren’t being met head on, as well as a lack of specificity in technological capabilities, stated governance, the justification measures, and timelines,” Peters said.

The report also raises concerns about accountability as far as use of new AI technologies is concerned. While SPD has promised not to use facial recognition technology, the RTCC software could, now or in the future, include other AI tools such as gait recognition, height-weight measurement recognition, and various other biometric identifiers, for which there is no clear mechanism for review.

SPD has said they may use object and clothing recognition technology, which the Community Surveillance Working Group called a “slippery slope.”

When The Urbanist reached out to Peters, he clarified that this slippery slope could lead to compromising civil liberties. He also suggested it would be better if identification technology of this kind could be limited to a defined list of prioritized items and mentioned it would be difficult to know whether there are additional possible or available capabilities of the software not listed in the SPD report.

The working group report dives into the risk of disparate impact of the pilot on minority communities in Seattle. It explains that the concerns are two-fold, as disparate impact can arise both from inherent inaccuracy and bias with the technology itself as well as the technology increasing exposure of people of color to police contact and the criminal legal system. The heightened surveillance zones are in neighborhoods with some of the highest-percentage of minority residents in the region, and overlap considerably with the newly passed drug banishment and SOAP zones.

The report says it’s “concerning” that SPD does not recognize these disparate impacts in their surveillance impact report. SPD instead said that because only public places will be surveilled, people can choose whether or not to be there, which will reduce any possible disparate impact. The Community Surveillance Working Group points out that this overlooks that people live in these communities and must go about their daily lives, which will require them to undergo surveillance to do so. It also ignores the city’s large unhoused population who will have no choice but to be in public the majority of the time.

Nevertheless, the SPD left the box beside “disproportionately impacts POC” unchecked in the Racial Equity Toolkit.

“I felt that with the amount of concerns we underlined, the timeline that the process is playing out over, and the communication between stakeholders, there was no possible way that anyone could make that claim [of no disparate impact],” Peters said.”

Peters raised concerns about the Racial Equity Toolkit process in general. “Without the proper accountability, allowing someone (let alone a law enforcement agency) to simply check or uncheck a box could render the toolkit into a rubber stamp,” Peters said.

The Community Surveillance Working Group, which is composed of six members appointed by the Mayor and City Council, concluded in their report: “After reviewing the information, a majority of the working group is unsupportive of any pilot deployment of these two technologies as described…The amount and urgency of the concerns and outstanding questions both warrant pause on pilot deployment.”

Only one member of the group was in support of implementing the pilot.

“The sentiment of the working group really reflected the fact that a large majority of the public comments we read and heard were against implementation,” Peters said. “The working group felt that going forward with these acquisitions may serve to further erode a significant portion of the public’s trust in SPD and negatively affect community relations.”

Despite being commissioned by the City to weigh in on this very topic, the working group was not given time at either recent public safety committee meeting to present their findings to the committee.

During the second meeting’s public comment period, Peters said, “I’ve made it clear and apparent that I and other working group members are happy to be a resource for the committee and council to answer questions or provide color to the assessment that we submitted. We should establish better representation of and support of the working group as a standard part of the sessions and beyond.”

When The Urbanist followed up with him, Peters added that it would be good to include a formal presentation from the working group whenever the council is considering using new surveillance technology in the city.

The Office of Civil Rights concurs

The Seattle Office of Civil Rights (SOCR) echoed many concerns of the Community Surveillance Working Group. In their own analysis, they highlight the insufficient outreach done to pilot communities. They also assert that the technologies aren’t effective for addressing gun violence and human trafficking, the stated purpose of the pilot. Finally, they conclude that because the technology in question will be placed disproportionately in communities of color, the pilot is likely to worsen racial disparities in the criminal legal system.

Derek Wheeler-Smith, the Director of the SOCR, called into question the efficacy of the technology, writing, “Research has shown that CCTV use is effective primarily for property crimes in parking lots and residential areas. A study reviewing 40 years of CCTV research found “no significant effects observed for violent crime.”

Wheeler-Smith highlights the “limited effectiveness” of RTCC software: “Research indicates that RTCCs have improved case clearance rates modestly for violent crimes, with a larger effect for property crimes.” He also mentions SPD already has an RTCC and wonders why no results from the current version are being shared.

At one of the committee meetings, James Britt, a Captain in SPD’s Technology Integration division, claimed the department has never used their current RTCC software. “I know it’s been discussed that Seattle PD has had a real time crime center, but in reality we built the room and never turned on any technology,” Britt said. “Some of you have had the opportunity to see that physical space, and it’s a very impressive space, but it’s not receiving any information. So in order for a real time crime center to truly be real time, it has to have real time camera feeds.”

Britt failed to state why the center hasn’t used already existent video footage from the department’s first wave of license plate readers and its body-worn cameras, or why the center was built and the software procured only to never be used, which would appear to squander taxpayers’ money.

The SOCR report also notes the dangers of storing the CCTV and RTCC data for up to 30 days, stating that this places the data in danger of being accessed to prosecute those seeking abortion and gender-affirming care, and those with immigration violations. It also calls out the dangers to victims of stalkers, noting “the potential for abuse is even greater with the RTCC than with the CCTV, as it will also contain Automated License Plate Reader data, which can help track someone’s movements throughout the city.”

Under the Racial Equity Toolkit section, the Office of Civil Rights report says, “This document cannot serve as a complete RET report because the City has not yet completed the necessary stakeholder engagement.” It also concludes that “there are several elements of the proposal that could worsen racial disparities.”

City council weighs in

City councilmembers added several amendments to both the CCTV and RTCC technologies. In addition to Moore’s amendment expanding the CCTV coverage area along Aurora, she also introduced amendments designed to provide more data protection.

The ACLU argued these data protection amendments will be insufficient.

“I appreciate the intent behind both amendments, but unfortunately, adding these stipulations to the vendor contract will not ward off the risk of the data being accessed and misused by other entities,” Sannon said. “It is possible that the vendor could be legally ordered to not inform SPD of a subpoena or warrant for the data, regardless of what’s in the contract. Further, even in cases where the vendor were able to inform SPD of a warrant or subpoena, it doesn’t mean SPD would prevail in a challenge in a red state.”

Councilmember Rob Saka sponsored an amendment that would require SPD to study the feasibility of using CCTV in other areas of the city, including the Alki/Harbor Avenue area of West Seattle. The amendment also directs SPD to evaluate potential use of CCTV for other crimes aside from gun violence, human trafficking, and serious felony crimes. At the most recent public safety meeting, Saka stated his concerns about the “tomfoolery” and “nonsense” that happen in the Alki area.

When discussing deploying surveillance technology in the Alki area, Saka said, “Is that likely going to prevent crime? Maybe, maybe not. Probably not. But will it undoubtedly help contribute to the feelings of safety in impacted areas? Yes, yes, it will.”

Council President Sara Nelson painted expanding surveillance as progressive and popular. “This is something that is happening in progressive cities across the country,” she said.

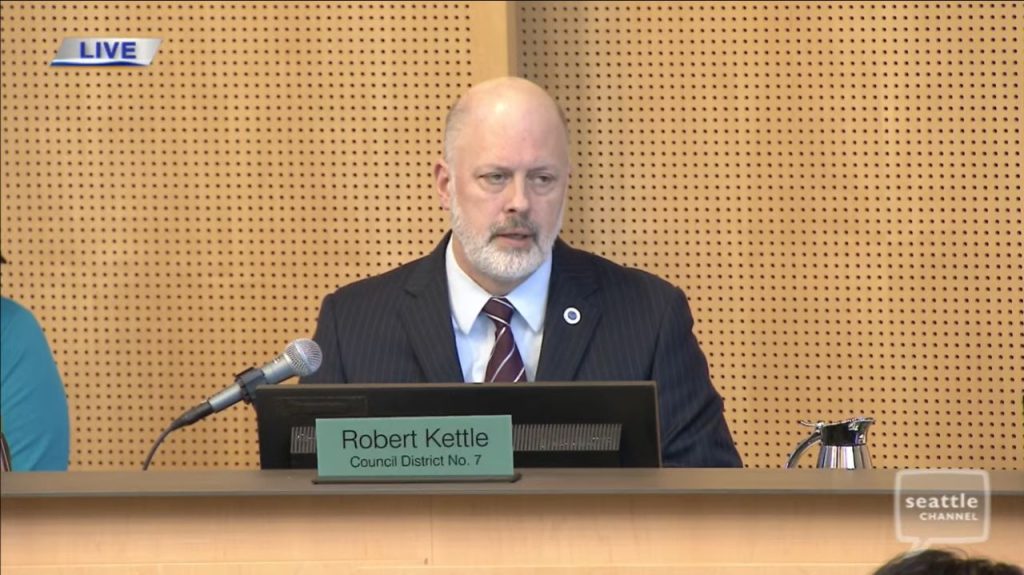

Public safety committee chair Bob Kettle disputed claims that there had been insufficient public engagement around this new pilot. “In terms of outreach to the pilot communities,” Kettle said, “there’s a lot of different types of outreach, and our decisions are informed by an incredible amount of outreach we’ve been doing ourselves.”

Peters has a different perspective.

“I think that at the end of the day, this all comes down to listening to people even when the feedback is inconvenient for your desires,” Peters said. “If a large majority of feedback at each layer is against what you’re doing, that should count for something, and you’d better have very clear data to show that you’re right.”

Civil liberties and criminal justice reform advocates look at the process as unfairly stacked against critics and engineered to justify a preordained outcome.

“The stakes are incredibly high at the intersection of technology, policy, and bias. The convenient thing to do is to cherry pick stories, selectively curate who you give a platform to in big moments, and push ahead,” Peters concluded. “The right thing to do is to take the time to rework and re-engage with the community until an acceptable number of concerns are addressed, and the safety benefits actually outweigh the privacy risks.”

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.