After three meetings delving into the proposal, the Seattle Design Commission voted Thursday against greenlighting a two-phase roll out of digital advertising and information kiosks in Downtown Seattle and several other neighborhoods. Proposed by the Downtown Seattle Association and strongly supported by the Harrell Administration, the kiosks are being touted as providing a big benefit for downtown visitors and as a major aspect of the city’s preparation for the 2026 FIFA Men’s World Cup.

The proposal would grant a third-party vendor — Ohio-based Orange Barrel Media — an exclusive contract to operate the kiosks. Meanwhile, a portion of the ad revenue generated would be earmarked for the Downtown Seattle Association. Orange Barrel Media operates its IKE (interactive kiosk experience) product in 18 cities across the US, with plans to expand to four more.

In declining to recommend the proposal, the Seattle Design Commission cited the impact to residents from the alternating ad messages on the signs, the lack of comprehensive public engagement completed to date, and a weak tie between the revenue generated by the kiosks and the public benefits that have been promised from the program to date. The final vote was close, with five members opposed to four in support. Several of the supportive commissioners expressed a desire to evaluate how the kiosks are working out after a more limited pilot program.

Ultimately, the choice to move forward will lie with the Seattle City Council, which will have final say over whether to approve the project’s 30-year permit. The issue likely won’t reach that stage until early 2025, with installation anticipated by the end of next year, according to the timeline provided to the design commission.

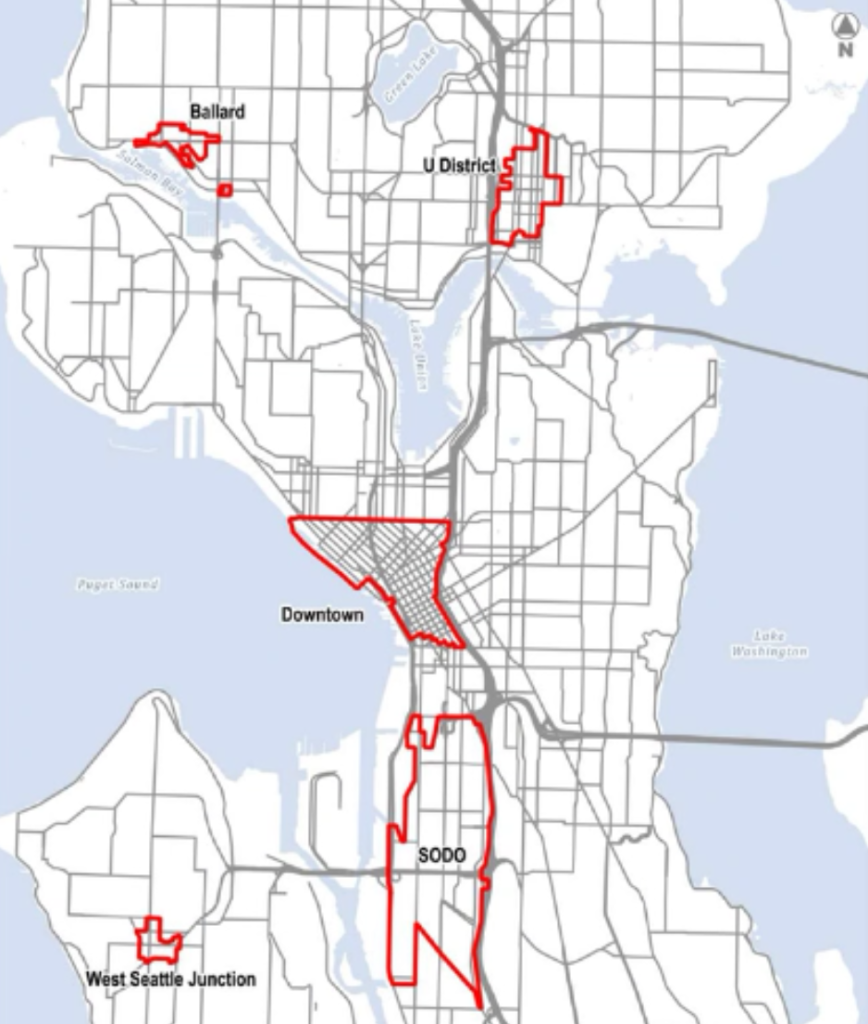

Under the proposal, 30 kiosks — manufactured by IKE Smart City — would be installed around Downtown Seattle, Belltown, and Denny Triangle as part of the first phase of deployment, notably excluding both the immediate area around Lumen Field and the newly completed central waterfront project. Under the second phase, the number of kiosks downtown would double to 60, with an additional 20 deployed to other neighborhoods including Ballard, the U District, SoDo, and West Seattle Junction.

Mayor Jenny Durkan considered a similar public WiFi and ad kiosk proposal from Intersection, another vendor that competes with IKE, but ultimately scuttled the proposal in 2018. That proposal went beyond kiosks and would have upgraded transit shelters across much of downtown, while generating as much as $167 million for the City over 20 years. However, the Durkan Administration cited privacy concerns as it shelved the idea.

Six years later with the IKE proposal, privacy concerns remain for some commissioners and residents testifying at the meeting. The proposal pledges to fully comply with the city’s privacy laws, and promises that kiosk cameras would only take photos when engaged in photo booth mode by users. Orange Barrel Media said it does not collect or sell personally identifiable information or include security cameras, like they have operated in some other cities’ IKE rollout. Separate from the kiosk proposal, Mayor Harrell is pursuing a major expansion of surveillance cameras.

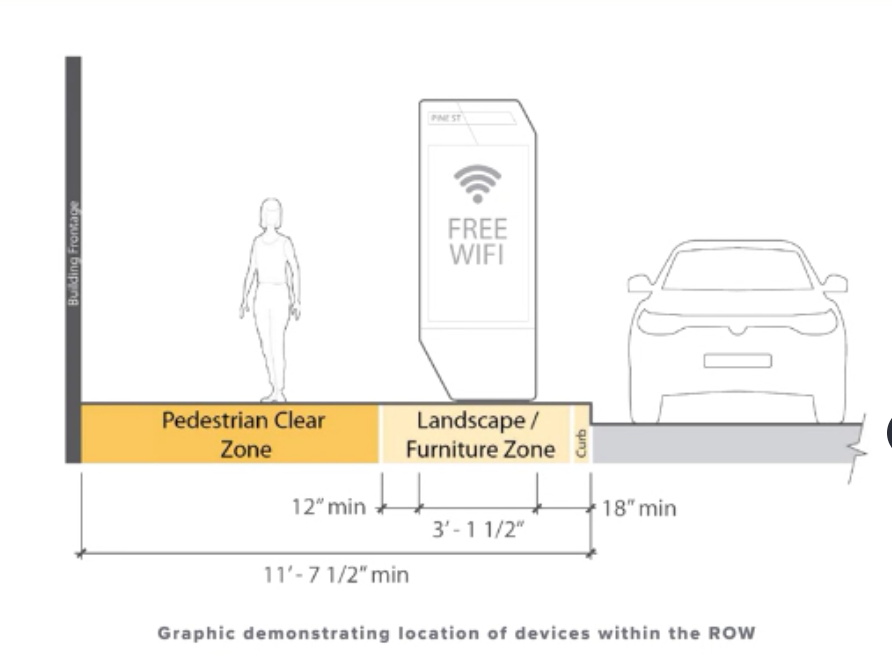

The proposed rules would allow kiosks to emit light 24/7, though the vendor pledges to adjust their brightness level by time of day. Kiosks would only make noise when a passerby uses one to call 911, a feature that the City of Seattle is touting as part of its efforts to improve public safety. On the other hand, some commissioners expressed concerns that kiosks could create a distraction or obstacle that contributes to road safety incidents.

When they’re not being interacted with, the devices would cycle through a slide deck of eight slides, showing each one for 10 seconds. Over the course of a year, the proposal stipulates 25% of those slides would be allotted to the City of Seattle and its partners, but that number could drop to just one of eight or 12.5% during Seattle’s peak tourist season, when ad space is at a premium.

Under the revenue-sharing agreement, the kiosks installed in the first phase would be expected to generate $1.1 million per year, revenue that would be distributed to the Downtown Seattle Association. In its presentation to the design commission, the DSA included a list of anticipated uses for that funding, including 10 downtown ambassadors who help visitors and keep public spaces clean, outdoor concerts and art installations, tricycles used by street cleaning crews and an electric street cleaning vacuum. Any revenue in excess of the projected $1.1 million would be shared with the City of Seattle.

DSA President and CEO Jon Scholes said the World Cup wasn’t the full impetus for the kiosk proposal, even as presentation materials have shown it as the target that planning is currently centered around.

“We haven’t proposed this initiative solely to satisfy the 750,000 wonderful people that will be here for a month and a half or so in June of 2026 — we think that’s going to be an incredible party for our city,” Scholes said. “We proposed this initiative back in 2018 or ’19 before we knew Seattle was going to be a host of these wonderful games. So we think there’s incredible local value from this initiative and this technology, both in the benefits the hardware itself provides and how the revenue is utilized.”

The design commissioner who was most vigorously pushing back on the kiosk proposal was AP Amrhein, who fills the designated role of an urban planner. Amrhein pointed to the city’s existing sign code, which explicitly prohibits flashing signage, and suggested that in his view, the sign code would supersede any term permit that the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) would issue for the operation of the kiosks. The term permit was a focal point for numerous commissioners who suggested it was the wrong vehicle for a 30-year project like this.

Amrhein pointed to engagement data that showed only 150 people had filled out an online survey about the kiosk proposal, and clearly suggested that most people had not been asked to weigh in on whether the deployment of kiosks across downtown was a good idea.

“I don’t believe there’s been sufficient public process to know the effects of the enjoyment of neighboring land uses,” Amrhein said. “I think these are beautifully designed devices, I appreciate the work that they’ve done to design them, but to me, when I think about the winners and losers of these, I don’t see local residents as being the winners.”

Several commissioners pointed out that program appeared geared toward tourists, rather than regular use by locals.

“If we have a roll out of 80 very large objects, that signifies a very particular design language, from this moment in time. [Given] a cell phone that we all currently have in our pockets, including people that are coming to visit the World Cup, it’s already a redundant object, and it’s magnified significantly larger than my body,” Kate Clark, the commissioner in the artist role on the board, said. “So why do I have to interact with that physical form over and over and over and over again, if the average of engagement is 10 times a day when we have 90,000 workers in downtown Seattle?”

While the project’s consultant team argued one more ad interface would hardly be noticed in the sea of advertising modern humans swim in, some commissioners did not buy that argument.

“I think we do have an urban environment that is actually pretty free of advertising. It’s almost non-existent except on transit busses which are not static and do not exist in one place,” said Zubin Rao, who fills the role of an architect on the commission. Rao pushed back on the idea that urban advertising is a foregone conclusion and also pointed to the city’s existing sign code.

There were some clear supporters of the idea on the commission as well, including Ben Gist, another architect. “I do feel like our city is a destination, and we do want to welcome and encourage visitors and tourists to our city. It’s a really critical part of our city reputation. So I think these could really be a benefit to people,” Gist said.

So far this concept really hasn’t been the focus of a citywide conversation around costs versus benefits. At Thursday’s meeting, those providing public comment in favor of the proposal either had direct ties to downtown groups, or to Business Improvement Areas (BIAs) in other areas of the city that would be poised to receive revenue from the rollout of kiosks. They included Wren Wilson, speaking for the Ballard Alliance, the BIA for the neighborhood’s core business district.

“The Ballard Alliance has had multiple opportunities to experience IKE kiosks both as a functioning kiosk in other major metropolitan cities, as well as during one-on-one conversations with IKE representatives to discuss details about the kiosk collection and viability in a city like Seattle,” Wilson said. “Without a doubt, our Seattle communities significantly benefit from high kiosks, particularly in a neighborhood like Ballard.”

But a number of downtown residents and workers have come out in opposition, citing a desire to not see the city’s pedestrian landscape cluttered with ads. Mark Reddington is one downtown resident who isn’t in support. Reddington is an architect and partner at the one of Seattle’s largest firms, LMN, with a deep background in civic design, and in June he wrote to the Design Commission asking for the body to vote no.

“My belief is that digital advertising on screens in the public space is not going to make a better experience or a better place, and that the history of Seattle has been to be very careful about the things we do with our public space,” Reddington told The Urbanist. “There are a lot of things that we have done that I think are terrific, but adding private digital advertising doesn’t seem to me as an amenity that will make it better.”

Even with this no recommendation from the commission, the kiosk proposal seems likely to move forward at the Seattle City Council, given the strong support from Mayor Bruce Harrell’s office. In a letter sent this week, the City’s Chief Innovation Officer Andrew Myerberg told the commission that the kiosk proposal was in alignment with Harrell’s plan for downtown activation, touting the potential benefits for public safety.

“[The Downtown Activation Plan] calls for bold, innovative thinking that matches the innovative spirt [sic] of Seattle,” Myerberg wrote. “The kiosk program represents such bold thinking, not only with respect to the technology of the kiosks themselves but also the public private partnership that would enable this benefit to be free of charge to the city.”

How much scrutiny the kiosks get from the city council isn’t yet clear, but this lack of recommendation from the design commission may prompt additional questioning regarding how exactly Seattle residents and visitors would benefit from such a public-private partnership.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.