Overhauling the ST3 program could help grapple with costs and improve outcomes.

Sound Transit recently revealed another meteoric rise in costs for the West Seattle Link project. Some boosters have already dismissed it as growing pains, a blip to absorb into spreadsheets as the agency marches forward on planned regional transit expansion.

What’s another $3 billion? Taxpayers are already on the hook for $46 billion over the next 22 years after all.

West Seattle Link is the canary in the coal mine for escalating costs. Sound Transit’s Final Environmental Impact Statement (EIS) unveiled a cost increase of $1.1 billion and $1.6 billion for the project, which had been estimated at $4 billion in the Draft EIS two years earlier. A few days later, the agency told The Seattle Times its best estimate is that the West Seattle Link Extension would cost between $6.7 billion and $7.1 billion, using its new more detailed “bottom-up” accounting method, rather than the blunter unit cost method in the EIS studies. The overrun had doubled, seemingly overnight.

King County Executive Dow Constantine, who chairs the Sound Transit board and lives in West Seattle, said it was crucial to forge ahead rather than overhaul the project. “The worst thing we could do right now is be paralyzed and slow the project. Delay decreases the benefit and increases the cost,” Constantine told The Seattle Times.

The problem, however, is that money doesn’t grow on trees. Local elected leaders show no urgency in enacting new revenue sources currently available under state law, state elected leaders aren’t champing at the bit to fork over money to Sound Transit directly or increase its debt capacity limit, and elevated federal dollars that are now flowing under President Joe Biden’s infrastructure law don’t matter much since they’re set to dry up in just two years — before several big ticket expansions break ground.

Without a ready source of new revenue, Puget Sound transit advocates are forced to care about project costs now and into the future, as much as we might not want to.

The harsh reality is that Sound Transit can’t just absorb cost increases on the magnitude of 40% — let alone the 67% to 77% increase the agency’s new bottom-up accounting method turned up on the West Seattle Link Extension. Those kinds of runaway cost increases eventually soak up all financing and debt capacity, making programmed project lists unaffordable.

There are some choices that can be made when that does happen, such as value engineering project elements, cost-effective construction methods, restraining community betterments, and reforming bidding processes — though it appears wishful thinking that bid reform would save money on the magnitude of the need. But the principal option Sound Transit leaders seem to be reaching for is continuing with expensive options that will almost surely mean delaying projects. The agency also studied cost-cutting measures in its last realignment, which largely focused on cutting stations to achieve the biggest savings.

Just three years ago, Sound Transit leaned on delays to carry out its last realignment. The project list was adjusted by resequencing projects, breaking some projects into phases, delaying project delivery dates by years, and quietly postponing low-performing project elements like parking. The capital program realignment was the second time Sound Transit had made dramatic changes to its capital expansion program in its then 27-year history.

Unfortunately, it seems like we may be headed for another realignment now — and likely a more painful one.

One signal something was up is that Sound Transit delayed its Annual Program Review Report, which evaluates assumptions for all current and future project cost estimates, delivery timelines, and capital program affordability. The report, originally due last spring, won’t come out until later this fall. Agency staff have been coy about why, but given that the West Seattle Link Extension was reaching the Final EIS issuance stage not long after the normal reporting timeframe, the report is bound to capture those recent cost increases. A delay of the report also signals some big changes to baseline assumptions for other capital projects, which were alluded to last week at the agency’s System Expansion Committee.

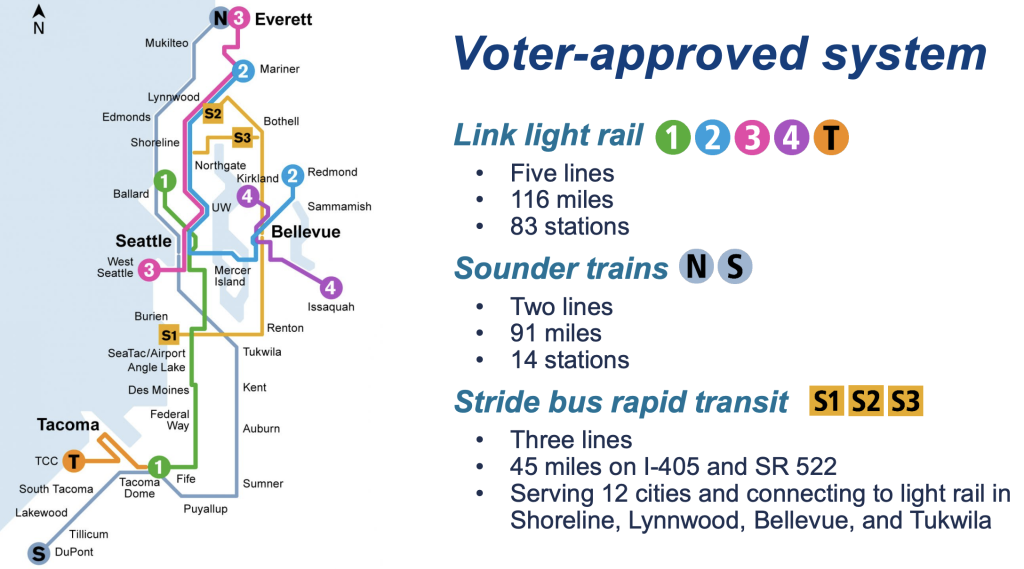

Consider, for instance, the Ballard Link Extension: If cost estimates jumped on the scale of West Seattle Link this year, that would add costs ranging from $3.2 billion to $8.7 billion compared to the Draft EIS — a 28% to 77% increase — on a project already estimated to cost $11.2 billion. The higher end of cost escalations would blow up the entire Sound Transit 3 (ST3) program, potentially setting projects back many more years, to a greater extent than it did a few years ago.

Due to earlier cost increases and planning delays, Ballard Link has already fallen four years behind the 2035 timeline proposed to voters when they approved ST3 in 2016. A $20 billion Ballard Link project would not be completed in 2039, as the tentative revised schedule proposes, let alone the fall back 2041 target.

Costs for the Ballard Link Extension project have rapidly escalated from the $6.4 billion (in 2023 dollars) that voters thought it would cost when they approved ST3 less than a decade ago. Given that the project involves many more miles of tunneling, deeper stations, and extreme levels of station box excavation, there is a very real risk that updated cost increases could exceed the rates that the West Seattle Link Extension just clocked in.

Cost increases were always a probable outcome for the ST3 program given significant escalations in real estate, materials, and construction over the past decade — cost increases that generally well exceeded core inflation. But not all of the cost increases have been inevitable. Poor decision-making and design choices made by the Sound Transit board, agency staff, and its cadre of consultants have contributed greatly to cost challenges.

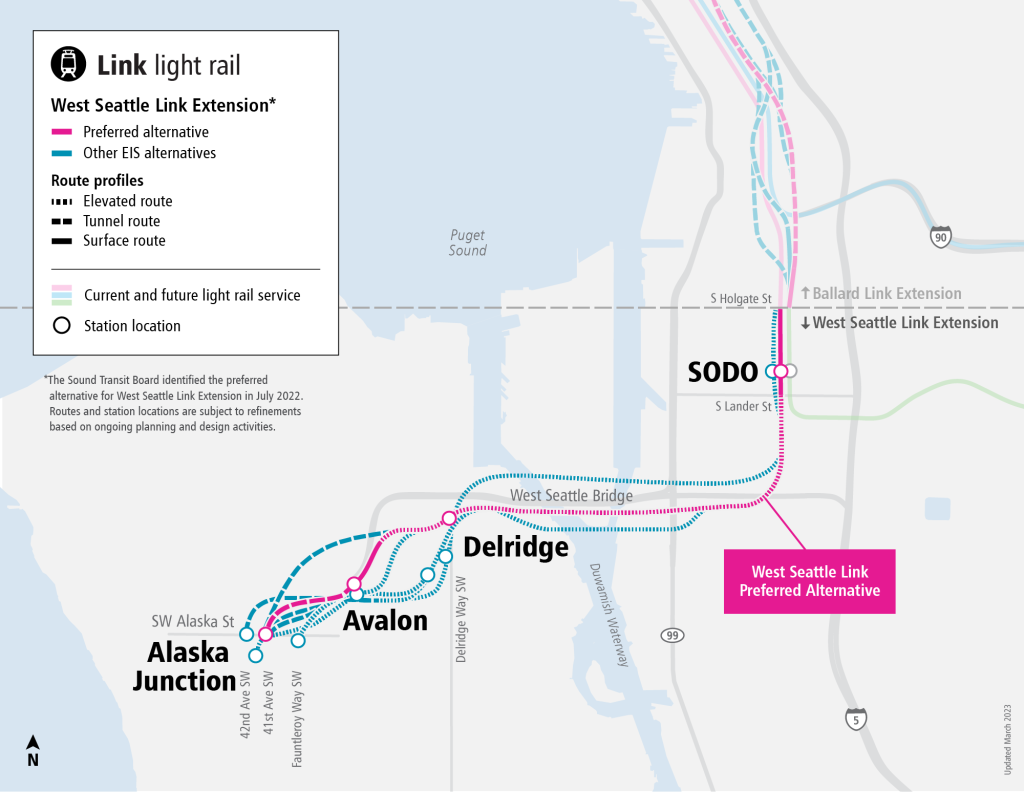

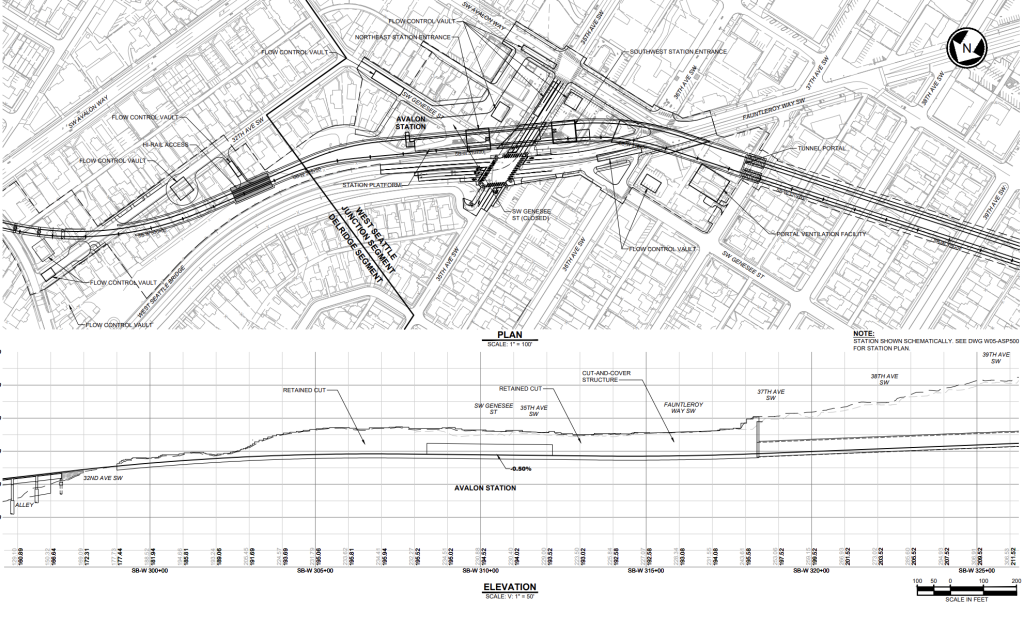

In the case of the West Seattle Link Extension, an expensive medium tunnel to the Junction and clumsy alignment through Youngstown wasn’t inevitable. Those were political choices to placate people who didn’t want to have to see light rail (much) in residential areas. And those choices were predicated on hoping and praying that tunneling, real estate, and more complicated construction methods wouldn’t lead to skyrocketing costs like they did between the midpoint and end of the environmental review process.

In another world, Sound Transit did the deeply pragmatic thing of routing the West Seattle alignment on Delridge Way SW and SW Genesee Street through Youngstown and then continued to the Junction using an elevated alignment on SW Avalon Way and Fauntleroy Way SW completely within the street. A version of this (unnecessarily putting elevated alignments outside of the street at great expense) was studied under the EIS process and was still found to cost $650 million to $1 billion less than the preferred alternative in the Final EIS. That doesn’t fully mitigate the latest cost increases disclosed in the Final EIS, but it does show that increases could have been far less dramatic, even under newer cost estimates for the project.

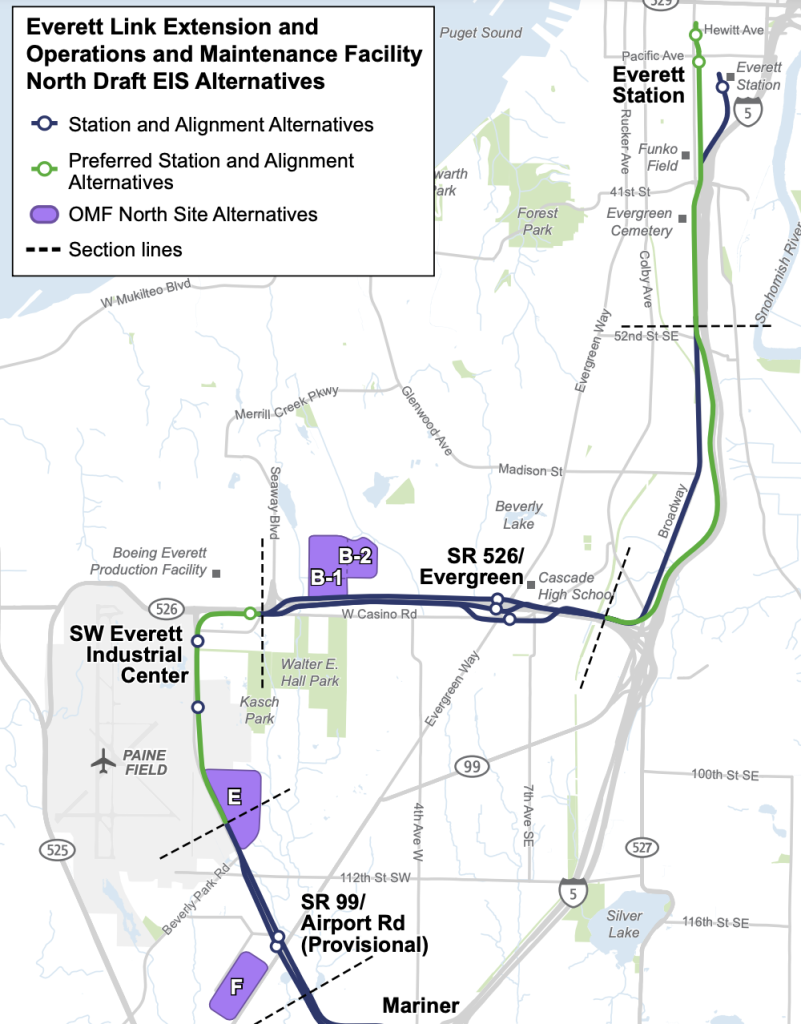

Likewise, the Sound Transit board has made head-scratching choices for the Everett Link Extension. Snohomish County officials have selected an indirect route deviating through Paine Field, through homes and businesses along Casino Road in South Everett, and through homes and businesses along Broadway in Downtown Everett. Adding to the problems, planned stations often involve sprawling footprints for discretionary features on large parcels of land.

The preferred alternative for the Everett Link Extension will displace hundreds of low-income residents and jobs, and comes with a high cost premium over simply locating elevated alignments and stations within streets like SkyTrain in Vancouver, British Columbia. Also worrying is that the deviation through Paine Field won’t directly serve the airport and ridership will largely be poached from existing bus service, providing little overall transit benefit, especially compared to a more complementary routing. An alignment could be placed on SR 99/Evergreen Way with several stations between Airport Road and SR 526 would generate much more ridership and do it at far lower cost.

Snohomish County officials, however, irrationally removed more direct SR 99 and I-5 routes from further study — and berated Sound Transit staff for even considering them as they did.

If and when we do end up in another realignment, it’s because of the choices our elected leaders and technocrats made along the way.

But this time around, harder choices will need to be made, and those choices ought to be based upon diligent cost-benefit and return-on-investment analyses. It’s evident that many projects simply cost too much per rider, like the West Seattle Link Extension that is slated to add just 27,600 riders to the light rail network at a cost of $257,000 per rider. Is that really the highest regional transit expansion priority?

The new cost reality should force some big changes, such as shelving the Issaquah-South Kirkland Link Extension for now, rethinking alignments for the Everett Link Extension, scuttling costly parking projects and the S Boeing Access Road infill station. It also is high time to jettison Sound Transit’s institutional principle of so-called “subarea equity” — a policy of proportional expenditure to revenues raised in five geographic areas. The balkanization of funding can lead to balkanized decision-making, pushing the agency to pursue bad alignments out of deference to the local subarea and to lose sight of the bigger picture: creating the most effective transit network for the entire region.

Thinking further outside the box, the board could also make better decisions around the Link extensions in Seattle by splitting them out of the conventional Link framework. One such idea is unifying West Seattle and Ballard Link into a single automated line using trains half the size and much smaller stations. An upshot of that is the line could ultimately deliver much higher frequencies and capacity at far lower costs and shorter construction timelines than currently proposed.

Policymakers could also bite the bullet by pursuing cheaper and faster construction methods, like fully elevated rail within streets and cut-and-cover tunnels, wherever reasonably feasible from a technical standpoint.

Doing any of this certainly won’t make everyone happy. It’s easier politically to design by committee and make decisions based on temporary construction impacts rather than transit outcomes. Breaking free of political inertia and overhauling ST3 is not easy, but it appears to be the only path to delivering high-quality rapid transit on anything approaching the original timelines pledged to voters.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.