City officials have big visions for Rainier/Grady Junction, but proximity to I-405, parking mandates, and prescriptive development standards may hold the area back.

Can a sea of parking lots and big box stores be transformed into a more walkable urban neighborhood with a planned bus rapid transit station as its focal point? The City of Renton is trying to make it happen, and wants to jumpstart development around Sound Transit’s planned South Renton Stride bus rapid transit station, potentially adding thousands of new homes to the area.

While some multimodal improvements are planned, the headwinds Renton will face in trying to create a truly transit-oriented neighborhood where very little pedestrian infrastructure currently exists will be considerable. The area being eyed is tucked into the bend of I-405 in South Renton, at the crossroads of multiple state highways.

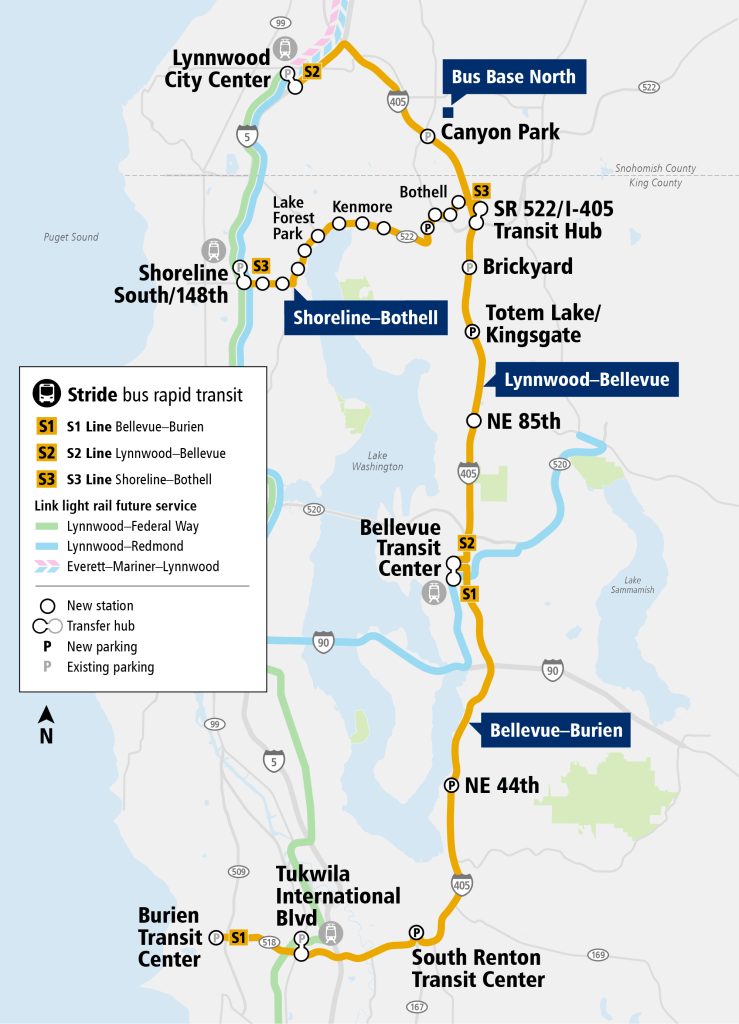

Sound Transit is working to transform a former car dealership next to King County Metro’s South Renton Park and Ride into a transit center that will serve the Stride S1 Line, part of its new highway-running bus rapid transit system that will ultimately connect Burien to Lynnwood via the Eastside. Though the Stride system has been plagued by delays, the S1 is set to open by 2028 and once it’s running, it will provide a quick connection to light rail at Tukwila-International Boulevard and in Downtown Bellevue.

Paul Hintz is Renton’s Principle Planner and has been overseeing the potential transformation of the parking crater and aspirational transit-oriented development (TOD) district currently referred to as Rainier/Grady Junction.

“The city saw the opportunity for this really auto-dominated area, characterized mostly by strip mall, retail, and older office buildings with really expansive parking lots, to be transformed into a unique TOD area with its own identity,” Hintz told The Urbanist.

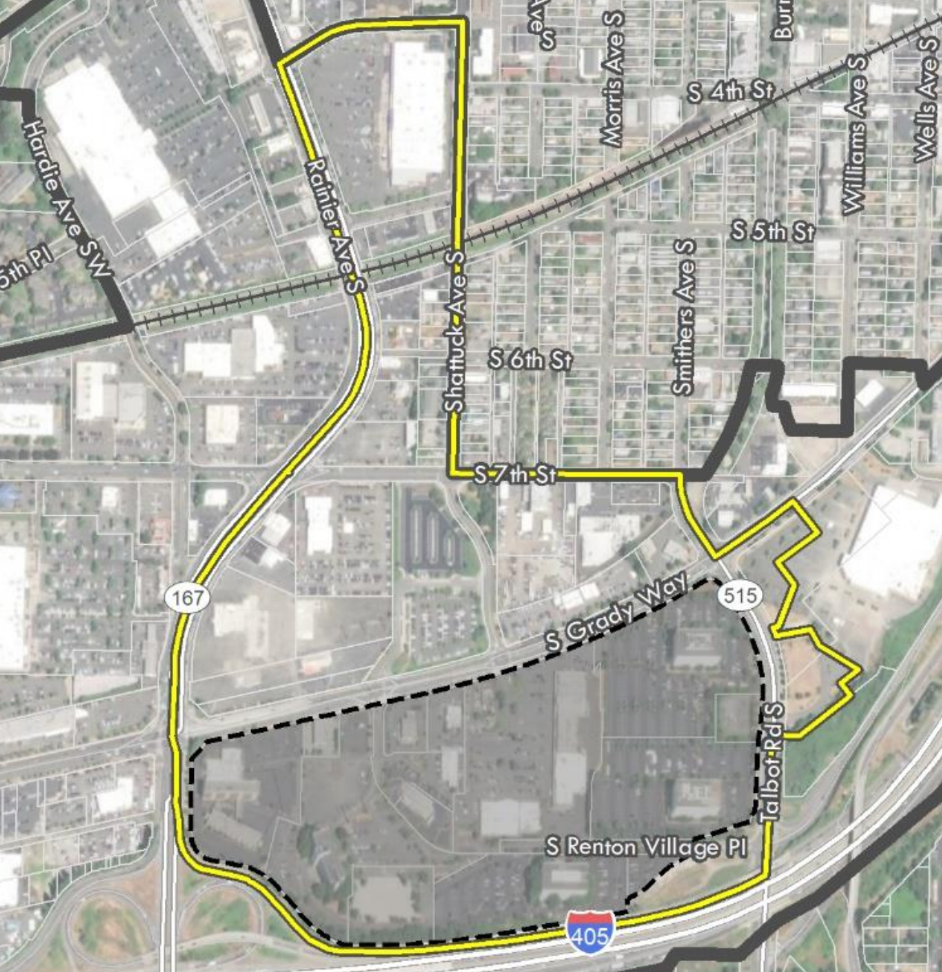

Three years ago, Renton adopted a Rainier/Grady Junction Subarea Plan, and is now poised to adopt an “action ordinance” which will streamline the environmental review that developers need to conduct to move new projects forward, with the intention of encouraging development. It’s a similar tactic as Lynnwood is using to create its City Center neighborhood amid a patchwork of strip malls and office parks. Renton’s ordinance covers just over 26 acres of land, much of which contain easements for high-capacity power lines, which could potentially limit the amount of developable land. The district covers a larger area, but much of the housing capacity would be jammed into the planned action area.

If fully built-out, Renton projects the greater subarea could accommodate just under 25,000 new residents, which is very optimistic and ambitious. Whether the district actually gets anywhere close to that will depend on how desirable and successful the neighborhood ultimately becomes.

Against the backdrop of these planned zoning changes and new development standards, the City of Renton has been exploring a potential property swap for the transit center, asking Sound Transit to explore whether the King County-owned former Red Lion Hotel next to I-405 would be a better location. The full logic behind asking for such a change, which would push the opening of the S1 line back by five years just as Sound Transit is poised to start construction, remains unclear. But such a change would almost certainly impact how the neighborhood ultimately develops.

Choosing incentives over mandates

A major choice that Renton planners faced in setting the ground rules for what’s essentially a brand new neighborhood was whether developers should be required to include affordable units in their buildings, or pay a fee to fund the creation of those units elsewhere. Cities like Seattle, Redmond, and Shoreline have all implemented inclusionary zoning policies in recent years that mandate a certain number of subsidized units or equivalent in lieu fee. But Renton decided to take another path, instead offering a baseline level of density by-right, with additional zoning incentives for developers who want to go taller by adding affordable housing and open space amenities.

“Comparing ourselves to Redmond or Shoreline is a bit of a stretch, because we’re not getting light rail, this is going to be BRT service.” Hintz said. “And we’re really grateful for seeing improved transit in our area, in our region, but it’s really not gonna have the same draw for developers, as a light rail station coming to town does. So we’re a little bit sensitive to asking too much of the development community.”

Throughout much of the planned TOD area, the maximum height mixed use buildings can rise to, without taking advantage of any incentives, will be 70 feet tall. City planners landed on the 70-foot base height limit primarily due to the economics of multifamily construction right now.

“When you talk about heights, it’s what you’re seeing going on: it’s 70 feet and you’re likely not going to see anything in the near future in between 70 and 150,” Matthew Herrera, another senior planner with the City of Renton, told the a City Council committee in February. “Maybe in the next 20 years, land values increase and the cost of construction catches up with that, but in the near term, that’s what we’re seeing right now.”

The maximum height limit with incentives is 150 feet, which is also the Federal Aviation Administration limit in South Renton. The affordability bonus is structured so that half of the homes created by adding additional floors (above 70 feet) must be set aside as affordable at 50% area median income. The open space bonus is set so that the open land set aside must equal 1.5 times the floor area bonus, but it also includes a transfer of development rights program that could potentially work to pool bonuses across sites and create a larger open green space.

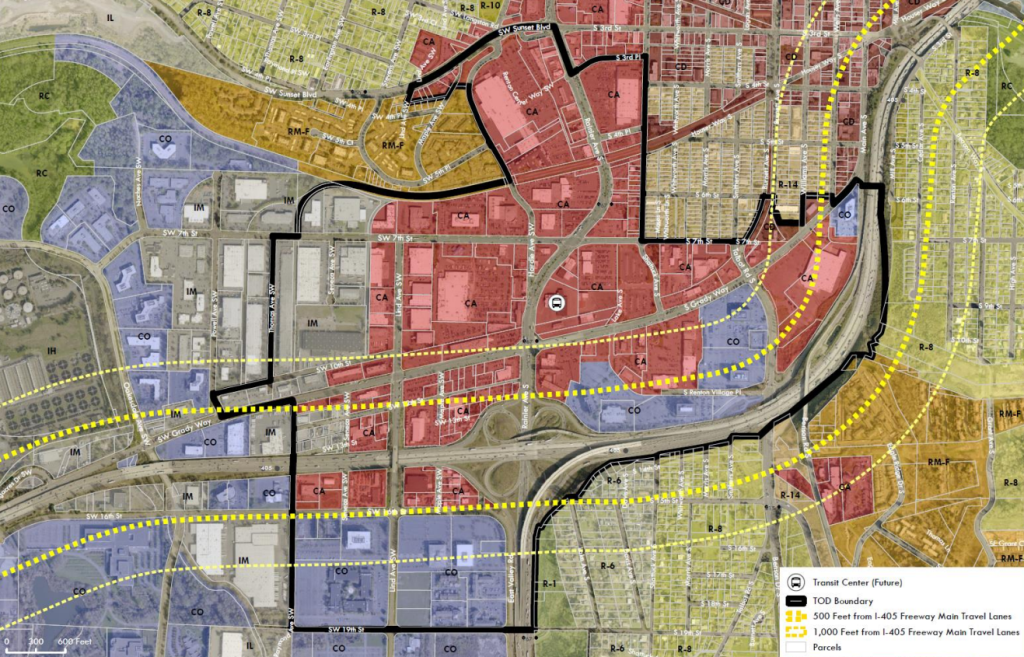

While the location of the Stride station provides great access to I-405 for buses, which will have their own dedicated lane from the highway ramp and transit signal priority at intersections, focusing development close to the highway reinforces a common pattern seen across the region, where multifamily housing is sited close to busy roadways and the noise and air pollution they generate.

The largest buildings allowed near the station are those that would be south of Grady Way, closest to I-405. To mitigate the public health impact of siting buildings close to one of the region’s busiest highways, a buffer of 500 feet would be put in place. Any new buildings constructed in that buffer wouldn’t be able to have balconies facing the highway, will have to provide double-glazed windows that do not open, and include heavy-duty air filtration systems. Architects will also be encouraged to “design buildings with varying shapes and heights to help break up air pollution emission plumes, increase air flow, and help reduce pollutants such as particulates and noise.”

Everywhere within Rainier/Grady Junction, developers will have to adhere to design standards that require buildings to be set back from the property line, and include step-backs for the upper floors. According to staff presentations made to the Renton Planning Commission and the City Council, these step-backs are intended to create a “pedestrian scaled-environment” and allow “better air circulation” but ultimately may serve only to create buildings that look over-designed, cost more to build, and perform worse on energy efficiency.

Hintz noted that the idea of requiring those step-backs came from the subarea plan, and how it envisioned a transition between the large apartment buildings that the city would like to encourage and the existing lower-density residential in the nearby South Renton neighborhood, which won’t see zoning changes.

“[Requiring the step-backs was] identified for buildings that will be adjacent to the South Renton neighborhood, where we’re gonna have a huge difference in height versus existing neighborhood and potentially what can be built. So it’s really imperative to make sure that we have step-backs there to ensure continued solar access, and to make sure that now that neighborhood isn’t seeing huge buildings kind of looming over them,” Hintz said. “But then, the subarea plan also identifies step-backs as being necessary to create the environment that we’re looking for, especially on that Main Street where we’re are hoping to create a really active pedestrian-oriented Main Street with a lot of ground floor commercial uses.”

Parking mandates are sticking around

In spite of the desire to create a vibrant, transit-oriented neighborhood, the City of Renton isn’t proposing to reduce existing requirements for developers to include off-street parking stalls with all units built, in most cases one-for-one. Units dedicated for residents with lower incomes will be allowed to have less parking — one space for every four units — an assumption that seems to stem from the idea that the only people without cars are those who can’t afford them.

Many cities around the US are ditching their parking mandates, recognizing the added housing costs incurred by requiring more stalls than builders think will be needed, and the degree to which subsidizing parking is a counterproductive to encouraging more multimodal transportation. Just last month, Spokane became the largest city in Washington to completely eliminate minimum parking requirements, after already taking the step of eliminating them near transit. For Spokane, the case was clear since homebuilders have warned mandating parking can make some kinds of new housing infeasible to build, and housing advocates have pointed out a large portion of parking costs are passed along to all residents, regardless of whether they rent a parking spot.

Nonetheless, Hintz defended keeping Renton’s mandates in place, citing some prior buildings that Renton has allowed to be constructed without parking that have created issues.

“In Renton, we’ve seen neighborhoods negatively impacted by significant reductions of parking for new developments. So we really feel that it’s still important for us to require off-street parking, so future residents don’t impact adjacent neighborhoods, or use business parking lots to park their vehicles,” Hintz said. While developers could apply for a reduction in required parking during the permitting process, a full buildout of the neighborhood without such parking mandate exemptions could add more than 5,900 stalls to the neighborhood, not even including required parking for commercial spaces.

Transportation investments may lag behind

With parking mandates staying in place, it will be an uphill climb to truly create a transit-oriented neighborhood, and the investments planned to make the area more accessible to people who want to ditch their car — or don’t have one in the first place — will be critical. But there things are expected to lag as well.

Many of the major roadways immediately around the Sound Transit station won’t see significant changes to make them more pedestrian-friendly. Five-lane Grady Way will remain one of the primary thoroughfares through the neighborhood, and will actually see an expansion of roadway space as part of King County Metro’s RapidRide I Line, set to open as soon as 2026.

“Grady Way is still going to be that main thoroughfare — it’s already actually a truck route,” Hintz said. “So there’s not much we can do there except to improve access north and south for pedestrians and bicyclists. That’s not really much we can do to take traffic out of there.”

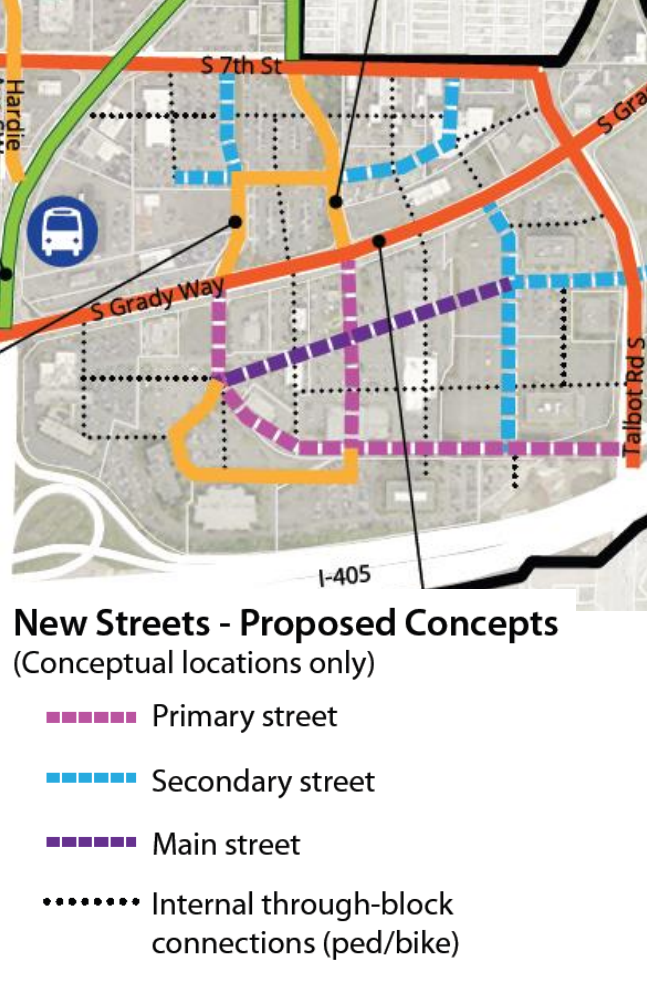

Instead, Renton envisions breaking up the “superblocks” that exist, particularly south of Grady Way, with new streets where cars are somewhat de-prioritized. Those new internal streets would still allow vehicle traffic, with one vehicle lane in each direction along with curbside parking. A central “Main Street” wouldn’t have any dedicated bike facilities, but the “primary” and “secondary” streets would have protected bike lanes. Subdividing the blocks even further would be midblock pedestrian walkways, required to be open to the general public.

“Those [new] streets are intentionally designed to not really welcome vehicle traffic — they’re meant to make you, as a driver of vehicle, not really feel like you can speed, not really think you have much width to drive in,” Hintz said. “So we really want to create that kind of closed feeling for vehicles that then consequently makes pedestrians and bicyclists feel more at ease.”

But it remains to be seen how quickly those additional connections with come to pass, and how useful they will be if they don’t provide direct access, instead making people walking and biking snake through behind the main thoroughfares. While there are some regional models for these new walkable streets built through new developments — Totem Lake Boulevard in Kirkland comes to mind — much rides on building getting these projects right for Rainier/Grady Junction to truly become what the City of Renton envisions.

Furthermore, the proposed new streets are merely conceptual. In other words, they could come to fruition and they could not. And yet much of the area’s promise of multimodal access hinges on how those facilities develop: with superblocks maintained, Rainer/Grady Junction will remain inhospitable to anyone trying to get around outside of a car.

Can South Renton transform into a more walkable neighborhood where transit is a primary mode and walking and biking connections are easy? The moves Renton is making now may be a step toward that vision, but all signs point to significant hurdles future policymakers will need to overcome so that it doesn’t become a transit district in name only.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.