Seattle Councilmember Cathy Moore questioned whether density can aid with housing affordability and claimed Mayor Harrell was seeking to roll back MHA fees.

A King County committee tasked with encouraging affordable housing policies is pushing Seattle to revise its 20-year growth plan to increase access to neighborhoods that have long been off-limits for lower income residents. The recommendations add yet another voice to the chorus calling for Seattle’s Comprehensive Plan update to go much further in allowing additional density than the original draft plan released by the Harrell Administration earlier this year proposes.

The recommendations came last week as the King County Affordable Housing Committee (AHC), made up of local elected leaders and housing subject matter experts from around the county, approved a comment letter on Seattle’s draft Comprehensive Plan, due to the state by the end of the year but months behind schedule. The letter included a fair amount of praise of the draft plan, but made it clear that it’s missing the mark in a lot of ways, particularly when it comes to the city’s “historically exclusive neighborhoods.”

The yardstick for evaluating the plan is the county’s own Countywide Planning Policies (CPPs), which set a framework for implementing the Growth Management Act (GMA) at the local level and which are approved by both the County Council and representatives of the individual jurisdictions within King County. References to which exact policies County staff found Seattle out of alignment with were sprinkled throughout Thursday’s conversation.

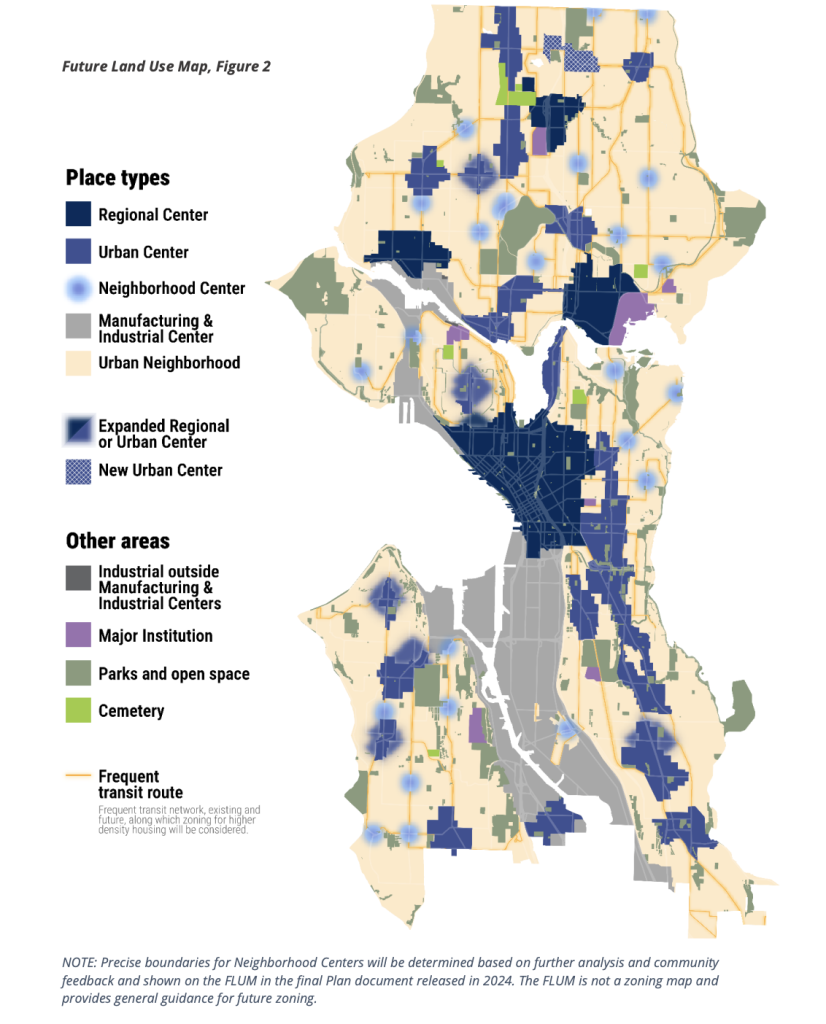

The primary areas of improvement identified by the county relate to Seattle’s formerly single-family areas, which the “One Seattle” growth plan proposes to rename to Urban Neighborhood zones but mostly keep unchanged, with only three or four units per lot the new baseline across most of the city. Restrictions will be kept in place on how large the footprints of new buildings can be, severely limiting the likelihood of adding much new housing in those zones.

“While the plan itself does propose many actions […] to address past and present exclusion, staff found that the actions taken together do not set reasonable expectations that historically exclusive neighborhoods will become affordable and accessible to low income households, particularly households below 50% of [area median income],” Carson Hartmann, in charge of managing the county’s Comprehensive Plan review program, told the committee in presenting the letter. “In this way, the city isn’t meaningfully repairing harm done to BIPOC households as required by CPP H-9, providing affordable housing to rent and own throughout the jurisdiction as required by CPP H-18A or filling gaps in policies and practices to eliminate racial and other disparities in access to housing and neighborhoods of choice, as required by CPP H-20.”

The letter calls out Seattle’s plan to incentivize the construction of affordable units through a unit bonus program, allowing four units on a lot to become six if those extra units are kept permanently affordable. “The AHC appreciates Seattle’s efforts to make affordable housing developments feasible in the Urban Neighborhood area through its affordable housing bonus proposal. However, the AHC does not believe six-unit buildings are a feasible project type for income-restricted affordable housing, particularly in areas with high land costs,” the letter notes.

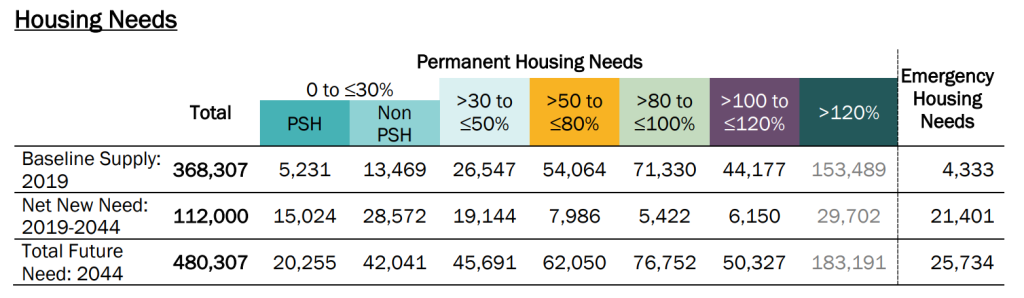

The committee notes that Seattle’s own analysis concludes that requiring buildings be less than 50 feet tall means units in those buildings would remain out of reach of Seattleites making half of the area’s median income or less, even as the city will need to add over 62,000 units available to that income range through 2044. “The AHC therefore finds that Seattle will not meaningfully increase access for 0 to 50 percent AMI households in the Urban Neighborhood area, which appears to still apply to most of the residential land in Seattle.”

The committee also takes issue with Seattle’s approach to making housing investments near transit, stating that the city “must take further action to maximize the benefits of these investments.” It calls out a lack of any clear boundaries for planned Neighborhood Centers — areas of increased density clustered around amenities. “The AHC cannot determine if Seattle’s draft plan proposes sufficient residential densities within walking distance of all of its future light rail stations, which could limit the potential development of income-restricted affordable housing in these areas.”

It notes the plan for increasing density directly along streets carrying frequent transit routes is vague, would leave out many areas of the city that are close to transit but away from arterial streets, and would expose future residents to higher levels of pollution. “Considering multifamily housing only along the street itself, as opposed to a larger radius from the street, would therefore place disproportionate exposure to pollution on lower-income residents,” it notes.

Seattle is far from the only city being asked to tweak its Comprehensive Plan — so far the Affordable Housing Committee has approved comment letters on 15 other jurisdictions, making a broad array of suggestions across them all. But how Seattle plans for growth impacts the entire region, and many of the items raised in the comment letter echo criticisms of the draft plan that have been raised by the Seattle Planning Commission, state legislators, and the chair of the Seattle City Council’s land use committee.

There was no official response from the Harrell Administration on the comment letter at last week’s meeting, with Office of Housing Director Maiko Winkler-Chin, who represents the Mayor on the committee, declining to respond. But District 5 Seattle Councilmember Cathy Moore did decide to respond to the issues raised, asking for more specifics from the committee on how Seattle could add more affordable housing to its lower density neighborhoods.

Moore expressed skepticism of the idea that simply densifying neighborhoods would open up more access for lower-income households, and suggested that the city was building enough market-rate housing to satisfy demand. “I don’t really understand what Seattle truly can do,” Moore said. “How do we fill that 0 to 50, 0 to 60 [average median income] gap? For me, that is the essential question in what’s facing Seattle — like we’re fine, we have plenty of 80 and above where we really need the housing is 30 to 60, and I don’t know how we do that.”

The response from County staff was that keeping Urban Neighborhood zones low density would continue to ensure that affordable housing gets built elsewhere.

“The land capacity analysis provided by the city in the draft comprehensive plan […] makes it very clear that denser buildings are required for affordable housing with subsidy, so five-over-two buildings. Multifamily zoning within zones that are currently lower density is a key strategy, and one that’s articulated both in the CPPs as well as the GMA,” Hartmann said.

But Moore pushed back, asserting that there isn’t a link between increased density and potential opportunities for affordable housing. Instead, Moore wanted the letter to more strongly promote Seattle’s Mandatory Housing Affordability (MHA) program, which requires multifamily development in Seattle’s densest neighborhoods to include affordable units or to pay a fee. The Harrell Administration has not yet stated whether it plans to apply MHA fees to increased density in Urban Neighborhood zones, a move that many housing advocates worry could make it even harder to build in those zones.

“I just think that that’s a flawed analysis, and I’d like to know where that analysis comes from,” Moore said. “We’ve got a lot of density in Seattle, and we don’t have a whole lot of affordability, and the affordability is going to come from subsidy; the private market isn’t going to provide affordable housing, and that’s why we need the MHA.”

With the Harrell Administration not set to deliver a final draft of the Comprehensive Plan to the City Council until early next year, there is still time for King County’s feedback to be incorporated into it. But despite all of the voices calling for the plan to go further than it currently does, it remains to be seen just how seriously that feedback will be taken.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.