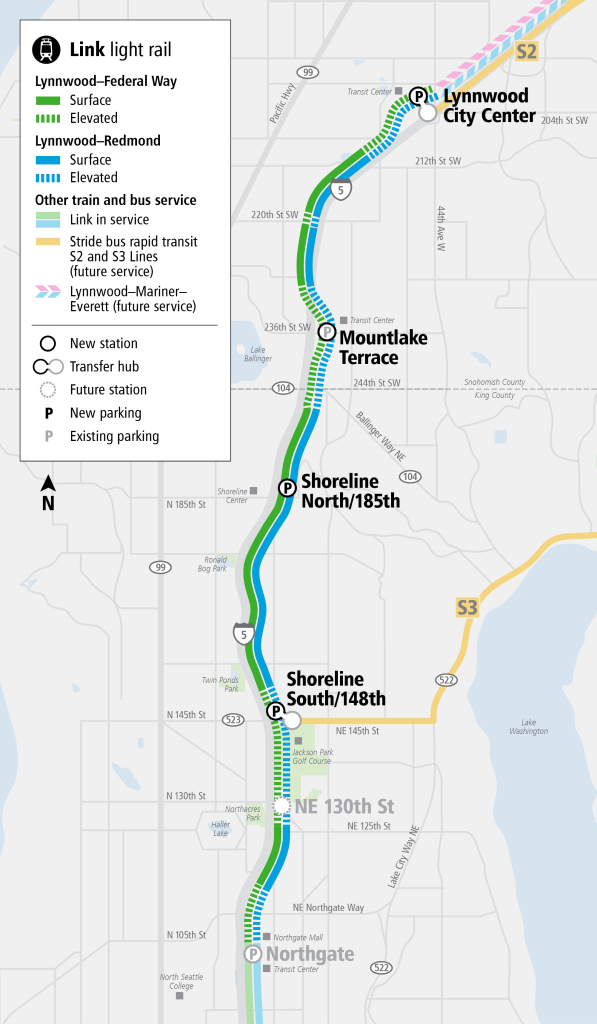

At 12:30pm tomorrow, light rail riders will be able to start traveling north of Northgate Station via the four-station expansion of Sound Transit’s 1 Line, which will reach Snohomish County for the first time. Those trains represent the culmination of a longstanding light rail commitment, approved by voters in 2008, but they also represent a major milestone for the local governments that have been working for years to develop the areas around the stations into destinations, to varying levels of success.

Much of that planning work predates the Lynnwood Link project, but the promise of 28-minute traffic-free trips to Westlake Station in Downtown Seattle has been an incredible catalyst without peer around the region.

Over the past few years, the cities of Shoreline, Mountlake Terrace, and Lynnwood have been working to add homes, businesses, and amenities close to their coming stations, with close to 10,000 new homes either delivered or in the pipeline across the three cities. That’s an impressive sum considering the three cities combined account for less than 24 square miles of land, and little more than 127,000 residents at last count.

City governments have been in charge of delivering more than just housing. They’ve been tasked with delivering new multimodal streets, parks, utilities, everything that makes up a complete community — work that will continue long past the start of service on Friday.

Shoreline doubles down, with twin growth centers

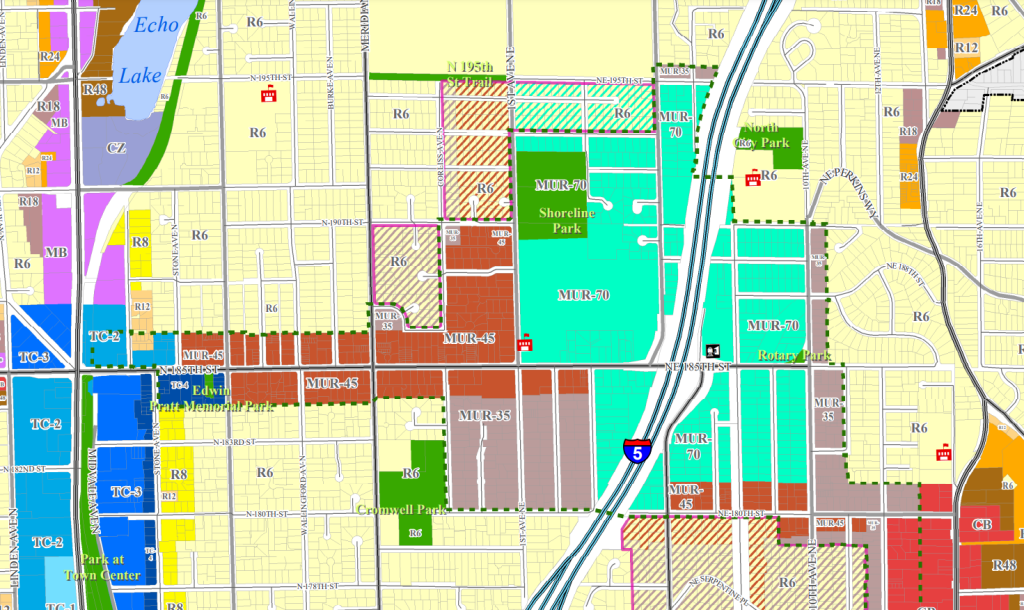

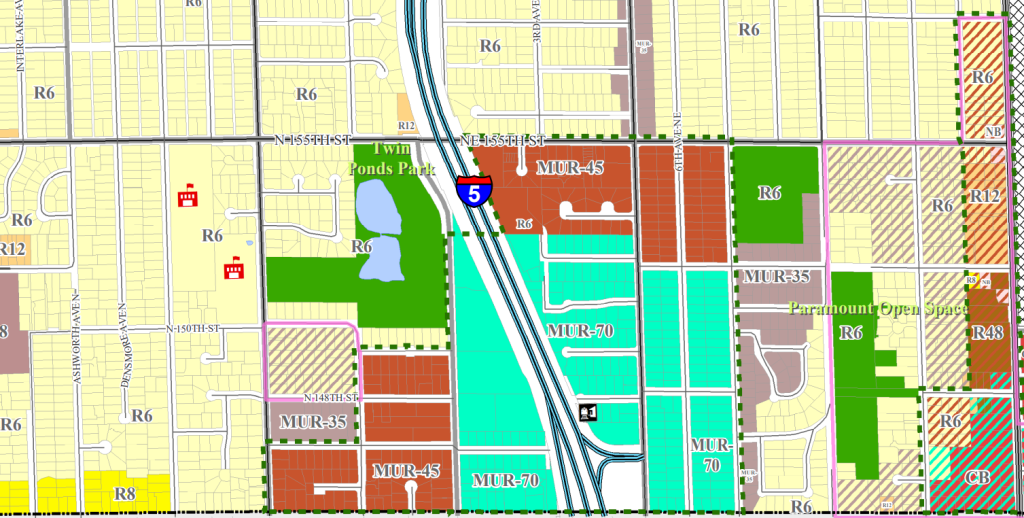

Few cities in the region have embraced transit-oriented housing development to the degree that Shoreline has. In 2015 and 2016, Shoreline adopted subarea plans for its two light rail stations, just east of I-5 at 148th Street and 185th Street, after launching planning and outreach efforts in 2013. On either side of I-5, height limits were significantly increased, with areas closest to the station going up to 70 feet. From there, the height limits descend on the periphery of the station areas, with areas of focused density concentrated along 185th Street connecting to Aurora Avenue and to the business districts of Ridgecrest and North City.

Christopher Roberts has been watching this process unfold the whole time, having been first elected to the Shoreline City Council in 2009. “We, as a council, previous councils, we all we agreed that it made a lot of sense to put increased density around the stations, I think that was a very intentional effort we made from those early days,” Roberts told The Urbanist. “The result has been a tremendous amount of housing, [a] tremendous amount of interest in developing new housing, especially around the 148th Street Station.”

To date, Shoreline has seen more than 3,000 units either completed or in the pipeline around 148th Street’s station and another 1,700 around the 185th Street Station. On a per-capita basis, Shoreline has added more housing than any other city in Washington in the past five years, outpacing both Seattle and Redmond. And the city isn’t showing any signs of hitting the brakes anytime soon.

“We recognized early on that businesses need people and people living near them to survive and thrive, and so when you add more density, you have more people to patronize our local businesses, and so we’ve seen tremendous investment by some of our local businesses that have expanded over the last two years,” Roberts said. He cites the Ridgecrest Public House as a success story, a business that transformed a former credit union into a neighborhood gathering space.

Shoreline has also been diligently working to redevelop the city’s street system to better handle walking and biking transit, via an all-of-the-above transportation strategy that is also trying to decrease congestion at specific intersections. A full revamp of N 145th Street to handle increased traffic, including transit and pedestrian traffic, has been able to move forward thanks to outside grants, as has the pedestrian and bike bridge under construction at 148th Street, a facility that will allow all of the new residents on the west side of I-5 to access the station without doubling down to 145th. “We’re a medium-sized city that has a big vision, and we have great partners.” Roberts said.

Where Shoreline has had limited success is getting its station areas to develop as complete neighborhoods, with full retail amenities. Several years ago, the Shoreline Council voted to require new developments within station areas to have ground floor retail rather than simply create spaces that could become retail spaces in the future. But while that has had some success, the station areas still have a long way to go toward becoming 15-minute cities.

“I’d love to see a place where people come, get off the station, and shop and find things to do right around the stations. That it’s not just a place for people get off and get go back home, the place where they sleep at night, to a place where people want to vibrant areas where there’s lots of things and a variety of things for people of all ages and interests to do,” Roberts said. “And that’s going to take continuing to work on making the areas more pedestrian friendly. It’s going to take developers and businesses to take an interest in the area — I know Shoreline is a great place to be, a great place to operate a business, but we need more people to have the same feelings.”

This Friday, the moment that Shoreline has been waiting for since 2013 is finally here.

“In many ways, it’s culmination of over a decade of planning, and I’m just so excited of the places that people are able to going to be able to get to without a car, without having to worry about traffic getting to Seattle and Downtown Seattle, that ease of getting to a game or getting to a play or going to the airport, is just gonna be so much easier to see the community come together,” Roberts said.

Mountlake Terrace sprouts a “Town Center”

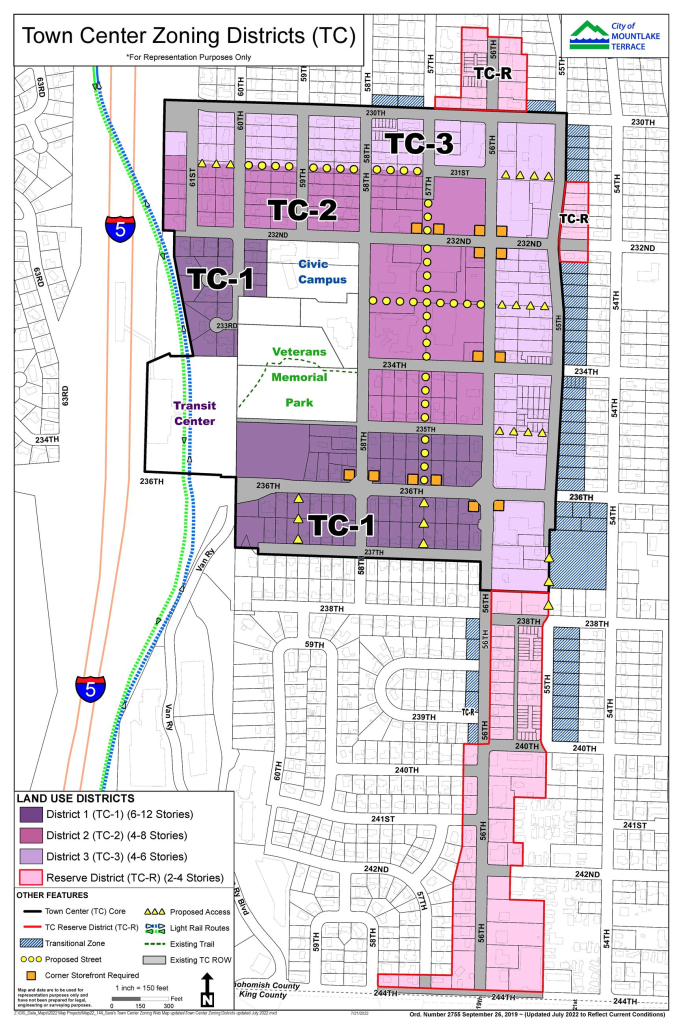

With a population of 24,000, Mountlake Terrace is the smallest city to see a Sound Transit light rail station open in its borders since Tukwila in 2009. Mountlake Terrace has been also preparing for the start of service for a long time, but the thing that initially set the city on the path to what it is today wasn’t a light rail station. It was a bus station.

In the early 2000s, Community Transit proposed to build a new parking garage at its existing park and ride lot along I-5 in Mountlake Terrace. The new garage would double the capacity of the existing facility for anyone looking to hop on a bus to Downtown Seattle, but elected officials and city leaders saw a greater opportunity to leverage the new bus station, creating a more compact district where residents didn’t need to rely on their cars as much.

“This would really put Mountlake Terrace on the map,” Mountlake Terrace Councilmember Laura Sonmore told the Seattle Times in 2003. With that investment planned, Sound Transit came in with the pedestrian bridge and I-5 bus station that buses could use without having to exit the highway.

In 2007, Mountlake Terrace raised height limits to seven stories on the central block of the so-called Town Center area, with heights tapering down from there. Since then, the Town Center plan has gone through multiple iterations, most recently in 2019.

“We are relatively small local government, but have [been] trying to keep up this sort of consistent drumbeat over the past 15 years to to make sure that we make the most of the changes that light rail will bring and opportunities that having reliable, accessible light rail service brings,” Mountlake Terrace Councilmember Rory Paine-Donovan told The Urbanist. “As a city, both staff and residents are looking at how you get more activity and the feel and vibe of the more vibrant town center, and I think we’ll really see a lot of progress towards that in the next two to three years with with some of these larger, mixed use apartment buildings being built, and I hope we got a mix of middle housing and sort of smaller infill development following that.”

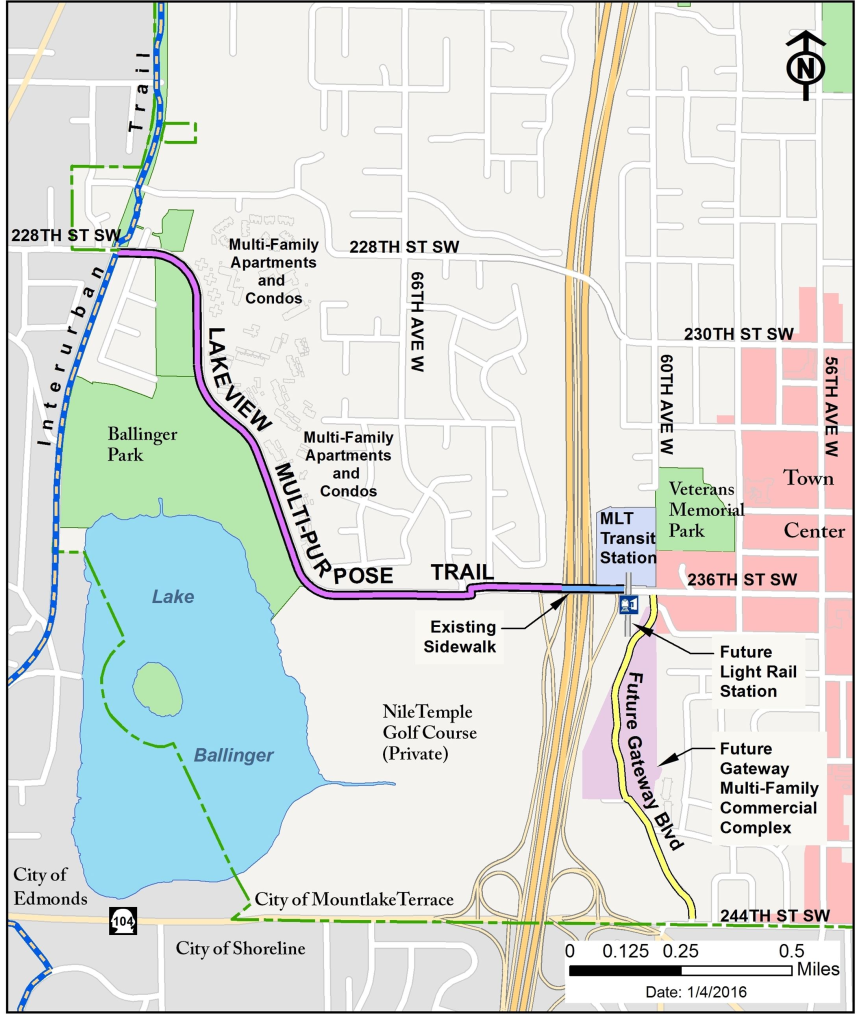

Another thing Mountlake Terrace did in anticipation of the growth around Town Center was build the Lakeview Trail connecting the existing Interurban Trail connecting north and south with the transit center. While more work needs to happen to connect the Interurban south into Shoreline, the Lakeview Trail provides an invaluable connection to Mountlake Terrace Station for people who are walking or biking. Opened in 2015, the trail was funded largely by a federal grant, secured by Governor Jay Inslee while he was serving in Congress.

Now that light rail is finally here, Mountlake Terrace’s Town Center will be closer than ever to the multimodal hub that was envisioned when Community Transit started planning its transit center more than twenty years ago.

“I think it represents a real, if not an immediate sea change for development up here in Southwest Snohomish County, it’s the beginning of a cultural moment that we can think about how to get away from having car trips being our only way to get around, to connect regionally with Seattle and our neighboring cities and northern Shoreline,” Paine-Donovan said.

Lynnwood coaxes a City Center into existence

Lynnwood’s journey to developing the City Center taking shape today, with hundreds of new homes sprouting up close to transit, also started before the 2008 vote to approve Sound Transit 2. As noted in our Lynnwood station preview, Lynnwood Mayor Christine Frizzelle told The Urbanist the idea dated back to the 1993 Legacy Lynnwood Project.

“I have a document that I keep on my desk that reminds me,” Frizzelle said. “It was 200 community members that came together over a long period of time that said: ‘these are our hopes and dreams for our city. This is what we want.’ I have maps. It shows Sound Transit right where it’s at. I have information there about bus routes. I have information about housing. And we are on track. We are doing what our community is asking for.”

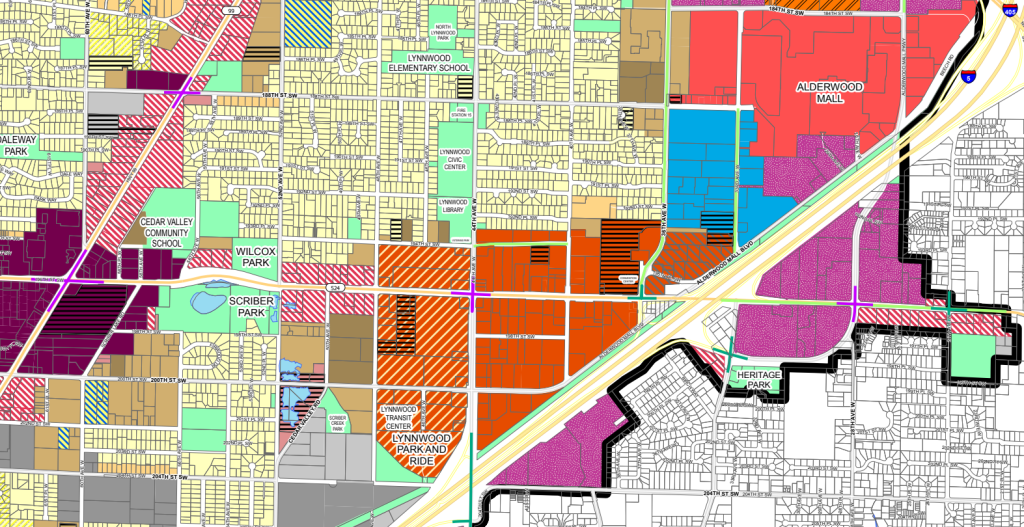

In 2006, the city adopted a new zoning map for the area that included the brand new Lynnwood Events Center. With visions of being the next Bellevue, the city copied Bellevue’s 1981 development plan and its tiered zoning, but factors like the 2008 financial crisis put a damper on the plan, no matter what the zoning was — a planned . But the ST2 vote that same year seemed to solidify the need to transform the area, pivoting it away from being focused around office buildings.

“Back in the 80s and 90s and early 2000s, it was much more envisioned to be an office space and a place to work,” Lynnwood Councilmember Nick Coelho told The Urbanist. “The core residencies were still going to be the traditional Lynnwood suburbs that you kind of expect in South Snohomish County, but with the Sound Transit vote, I think there was a big shift, and thankfully, we have been very much on the side of getting that population base that’s really necessary to provide the economic base for a vibrant downtown core.”

With Lynnwood associated with Alderwood Mall and its car-centric retail model, a model that the city wants to keep in place for the benefit of its budget, the City Center neighborhood is intended to provide a more walkable counterpart. “I think we’re doing the right things to make not only the housing situation work for our unique position in the region as a commercial hub, but also really to develop a vibrant downtown,” Coelho said.

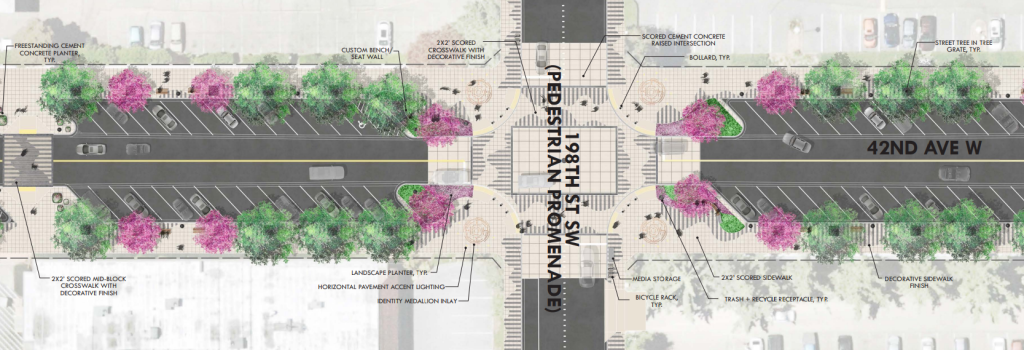

After Lynnwood spent $48 million to overhaul 196th Street SW, the primary thoroughfare through the neighborhood, by widening it to add business access and transit (BAT) lanes, wider sidewalks, and planted medians, the city’s plan is to create additional street connections that break up the large blocks that exist in the City Center. Plans for 42nd Avenue W, a street that doesn’t exist yet in Lynnwood, include wide sidewalks, but also back-angle parking and two general purpose travel lanes. So while light rail’s presence may encourage some car-free travel, most of Lynnwood’s built environment isn’t there yet.

With Lynnwood remaining the primary hub for light rail in Snohomish County until well into the next decade, bus riders from across the county will continue to rely on the city to make connections. But the number of people who call Lynnwood City Center home will only continue to increase as well, all factors that will continue to put pressure on Lynnwood to accommodate people who are trying to get around without a car.

“It’s the culmination of decades of work. It’s the realization of the potential of Lynnwood,” Coelho said. “We’re kind of informally known as a crossroads, with the I-5 and I-405 corridors kind of converging in our city, but I think we’re going to become much less of a place that is just in between other cities and much more destination that is at the center of everything. I think this is really the turning point for the city as it becomes a regional hub. And I’m really looking forward to it, and I think most of our residents are too.”

Correction: An earlier draft incorrectly stated that 1,200 units were in the works near Shoreline South. The correct figure is more than 3,000.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.