SDCI finally released its report on fixing design review, but most changes remain a year away.

Three years after the city council tasked the Seattle Department of Construction & Inspections (SDCI) with examining how to reform its cumbersome design review process, SDCI released its stakeholder report on the program in July. Despite finally releasing the report, the department still remains nearly a year away from making substantive changes to design review.

Bogged down by a contentious stakeholder process, and thrown for a loop by the passage of state legislation (HB 1293) in 2023 that curtails design review processes statewide, SDCI still appears committed to making only minor tweaks to design review rather than major reforms beyond state minimum standards. Starting in June 2025, HB 1293 will require that all design standards be “clear and objective” and set a maximum of one public meeting per project.

“The Design Review [statement of legislative intent] and stakeholder process [were] helpful in identifying program outcomes, gaps in equity, and stakeholder recommendations for how to address those gaps or refinements to the design review process,” said SDCI spokesman Bryan Stevens in an email. “We expect the legislation for these changes will be completed by the June 2025 state deadline.”

In November 2021, the Seattle City Council directed SDCI to look at ways to improve design review, which ostensibly exists to implement design guidelines, improve the exterior aesthetics of multi-family residential buildings, and to promote designs that better fit into Seattle neighborhoods. But housing advocates, architects, and developers have long complained that the program substantially increases the time to issue building permits, increases the cost and complexity of projects, focuses on intangible aesthetics, and makes the permitting process unpredictable.

“The primary harm it causes is the uncertainty of the delay,” said Scott Berkley, an organizer with the group Tech 4 Housing, which advocates for abundant housing options. “When developers can’t reliably predict how long it’s going to take them before they can begin construction, that puts their financing at risk and makes projects less viable.”

In the past several years, Mayor Bruce Harrell’s office has taken several small steps to reform design review and exempt some projects from the process. A pandemic-era exemption for affordable housing projects was renewed in 2023, and the exemption was extended that same year to multi-family housing projects that include Mandatory Housing Affordability units on-site.

This April, the mayor’s office proposed exempting residential, hotel and research laboratory projects in the greater downtown area (including downtown, First Hill, Uptown, and South Lake Union) from design review. SDCI submitted the legislation to the city council in July. The bill will receive a hearing on September 4, and a possible land use committee vote on September 18, according to a spokesperson for Councilmember Tammy Morales, who chairs the committee.

“I certainly think this is a step in the right direction,” Berkley said of the legislation. “But the housing crisis in Seattle is past the point where these small, incremental changes are really addressing the problem with the urgency it demands.”

Berkley also observed that if downtown could benefit from design review exemptions, other areas of the city deserve relief as well. “We object to the implication that maybe this is good enough for areas with higher renter populations,” he said, “but we somehow still need to protect other neighborhoods that have higher rates of home ownership.”

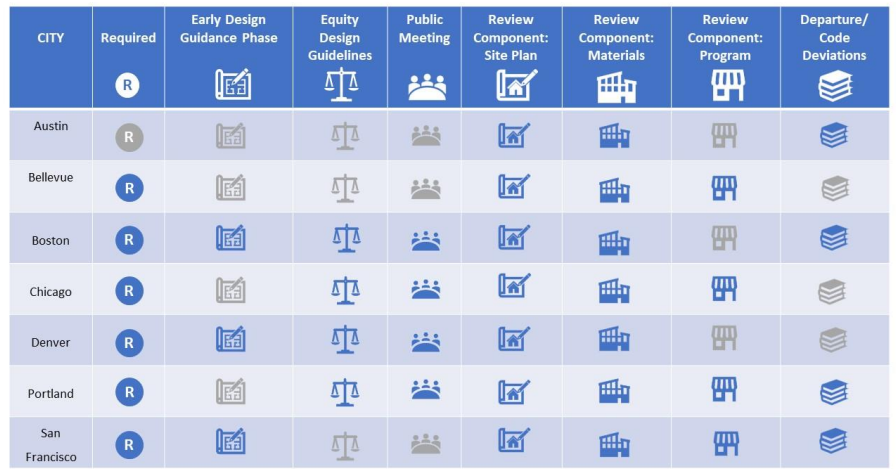

The three-year process to create the stakeholder report was fraught with confusion and controversy. In its statement of legislative intent or SLI, Seattle City Council asked SDCI to look at the impacts of design review through a racial equity lens, while also instructing the department to document how long the process takes, how often departures from guidelines are granted, and whether the program increases housing costs. It also asked for a review of similar programs across the country, and asked for a list of recommended steps to modify and improve the program.

As the report makes clear in its opening letter, there was early confusion about how much emphasis was to be placed on racial equity analysis versus improving the efficiency of the program. The consultant hired by SDCI, Paradigm Shift, eventually resigned from the group after the mayor’s office added more representatives on behalf of organizations such as AIA and Seattle for Everyone. These groups were, admittedly, more focused on broad program outcomes rather than a narrow racial equity analysis focused on boosting participation from underrepresented Black, Indigenous and people of color (BIPOC) communities, but largely leaving the program intact – perhaps with even more layers and hurdles.

In its resignation letter, Paradigm Shift representatives Sofia Voz and Ti’esh Harper wrote, “From our point of view, if the intent of the SLI was to analyze ‘whether the program creates barriers to participation for BIPOC residents, either as applicants, board members, or public participants, and whether the program creates or reinforces racial exclusion’ the stakeholder group should have prioritized members who can speak intimately about this topic.”

Paradigm became frustrated that its attempts to analyze the equity impacts of design review were bumping up against efforts to streamline the process. “The desire to make changes was rooted in pressure primarily from the development community,” they wrote, “and more specifically, in money and the current cost of the process.”

Stevens, with SDCI, addressed the controversy by noting that both the mayor and city council, while focused on improving equity outcomes from the program, were primarily concerned with reducing its complexity.

“Both the Mayor’s Office and Councilmember Strauss verbally stated throughout the process that one of the underlying principles of the SLI was to decrease the complexity of the design review program, streamline the permit process, and increase program predictability while making public engagement more equitable, all in an attempt to increase housing production and affordability in Seattle,” Stevens said. “While the scope of the SLI remained intact, it was important to clarify that program evaluation and improvements were the overarching goal.”

Howard Greenwich, research director for Puget Sound Sage, hopes that the city will modify or replace design review with a system that is truly responsive to the needs of residents threatened by gentrification and increasing housing costs.

“In places that are not at risk of displacement, high opportunity areas, I think design review, by and large, goes away,” Greenwich said. “Instead, it’s replaced with a community planning and governance process like the ISRD [International Special Review District] in BIPOC-majority neighborhoods. Whether it’s SDCI staff or Office of Planning & Community Development staff bringing together stakeholders who can not only do the planning for the neighborhood, but also can evaluate projects and whether they fit within the community vision.”

David Neiman, an architect with Neiman Taber who served on the Ballard design review board, hopes SDCI will do more than follow the letter of state law requiring design review to be more simple and objective.

“I hope the city won’t try to create a design review program that is somehow nominally compliant with state laws, but still maintains a bunch of the process,” Neiman said. “I think that’s a terrible outcome. It’d be meaningless kabuki theater, because the state law doesn’t allow your program to in any way engage in subjective judgments.”

SDCI’s 179-page report, like the stakeholder process itself, is complicated and takes its time in getting to the point. Asked to succinctly summarize the conclusions of the report, Bryan Stevens of SDCI listed six takeaways in an email response, which are summarized here:

- Rewriting and simplifying design guidelines, including adding equity-focused guidelines;

- Fewer design review hurdles for housing by allowing for more departures from the land use code; requiring minimum floor area ratios to prevent under-developed land; and increasing thresholds so fewer properties must go through design review;

- Increasing predictability of the permitting process and increasing staff capacity to improve consistency and reduce approval time;

- Replace eight district-based design boards with one centralized and “professionalized” design review board by paying stipends and requiring expertise, such as architecture or engineering backgrounds; recruiting more members from BIPOC communities, and training boards to promote racial equity;

- Improving community outreach through more concise, simple language, and better engagement with BIPOC communities;

- Meaningfully embedding racial equity throughout the design review program, including creating program missions focused on equity; creating an accountability framework, and convening a group from BIPOC communities to evaluate how well this accountability framework is working.

Stevens said that SDCI, over the past year, has been “working to identify how design review changes could respond to both the Design Review SLI Stakeholder recommendations and the requirements of HB 1293.” Though SDCI is planning to propose reform legislation by the state-imposed deadline of June 2025, some changes to the program are already in the works, he said, including:

- Reforming the design review board appointment process to increase BIPOC and historically underrepresented voices on the boards;

- Rewriting design review documents with concise, plain language, including websites, instructions, design review reports, etc.;

- Increased training for design review boards and reviewers to improve review times and ensure consistent application of design guidelines;

- Racial equity training for design review boards and reviewers.

Berkley, with Tech 4 Housing, questions SDCI’s approach, with long timelines and minor tweaks to the program.

“I think we need to start approaching things with urgency to fix the problems, and not this hesitancy that says we can’t make any mistakes and we can’t cause any person to be worse off,” he said. “We need a bias towards action – something the city has been sorely lacking over the last several decades.”

Referring to the infamous Queen Anne Safeway multi-family housing redevelopment that took seven years to permit and build and whose design review squabbles over minor aesthetic details sparked calls for reform, Berkley said, “Seattle isn’t facing a brick color crisis because of a lack of qualified architects. We’re facing a housing and homelessness crisis caused by a lack of housing.”

One question the city council asked SDCI to address in its stakeholder process was how much design review, on average, adds to the cost of a multi-family housing development. The report didn’t answer that question. Stevens said this was because the consultant hired by SDCI to do the analysis only heard anecdotally from developers about the added costs – and that to accurately determine those costs, the group needed more data. “Developers would need to share their proformas with this data, comparing similar types of development with and without design review,” Stevens said. “Those proformas were not made available to the consultant.”

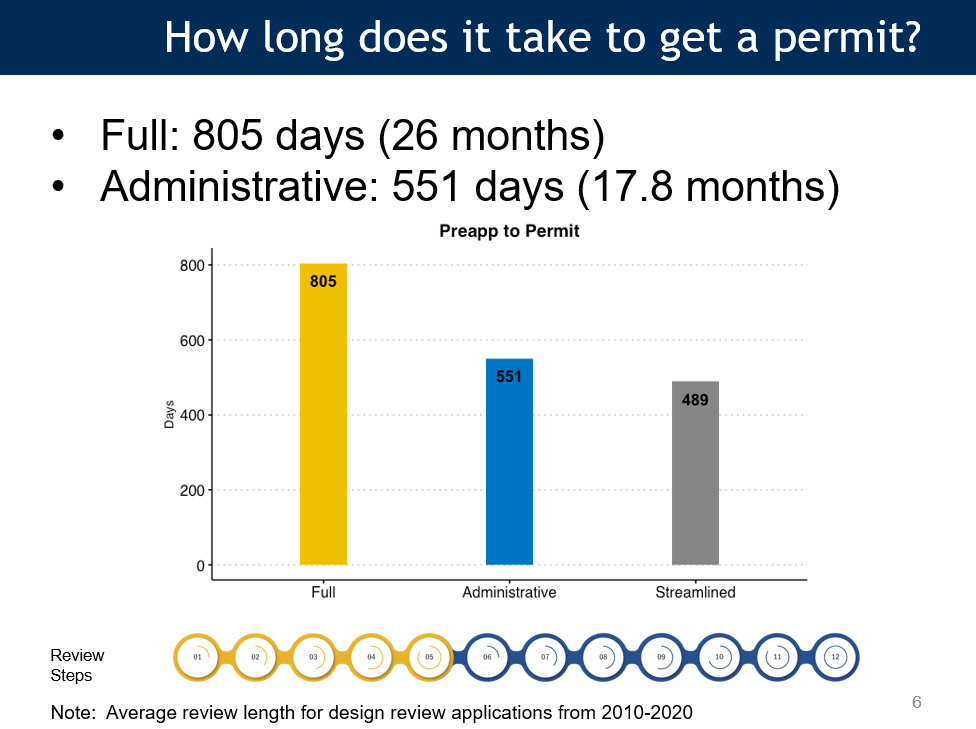

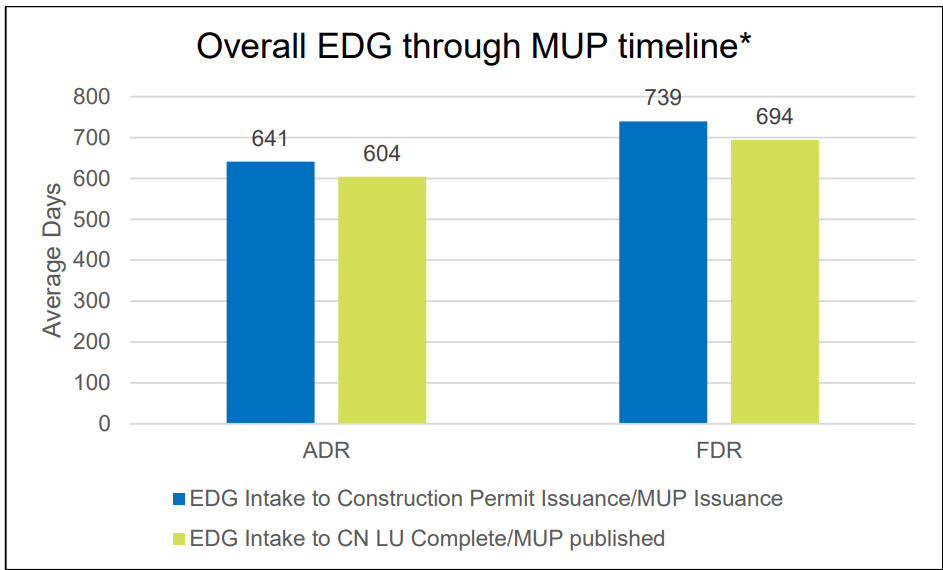

Though a study by ECONorthwest commissioned in 2021 wasn’t able to estimate the added costs of design review, it did find that projects that went through full design review took 26 months to receive a permit on average – while projects that went through administrative design review took a little less than 18 months on average.

Neiman said taking a project through full design review substantially increases costs for his firm, and that’s passed on to the developer and renters. “It adds somewhere between nine months and forever to a given process,” Neiman said. “If it goes well, it adds the better part of a year and adds at least $100,000 in architects’ design time. And probably significantly more than that in the cost to the project in terms of added design features and time delays.”

While many comments submitted during the stakeholder process call for eliminating design review altogether, Stevens said SDCI isn’t considering that option. “While the option of eliminating design review was mentioned by a few stakeholders, other stakeholders pointed out that ending design review would have a disproportionately negative impact on BIPOC communities, since that’s often the only point of communication they have with city decision-makers,” he said.

Neiman hopes the process might be replaced with objective guidelines. “Instead of having 100 things you must do, maybe have: here are 20 prescriptive rules; pick seven,” he said. “If you have porches facing the street, you get a couple points. If you put brick on your building you get five.”

As for extensive public meetings to tell architects and developers the best way to design apartment buildings, Neiman hopes that will become a thing of the past. “We don’t have public meetings to decide what kind of restaurant you get to open,” he said. “We don’t have public meetings to decide […] what foods a grocery store will carry.”

Andrew Engelson

Andrew Engelson is an award-winning freelance journalist and editor with over 20 years of experience. Most recently serving as News Director/Deputy Assistant at the South Seattle Emerald, Andrew was also the founder and editor of Cascadia Magazine. His journalism, essays, and writing have appeared in the South Seattle Emerald, The Stranger, Crosscut, Real Change, Seattle Weekly, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Seattle Times, Washington Trails, and many other publications. He’s passionate about narrative journalism on a range of topics, including the environment, climate change, social justice, arts, culture, and science. He’s the winner of several first place awards from the Western Washington Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.