Centrist councilmembers tout regressive “tough on crime” policies that have failed in the past.

The Seattle City Council continues to struggle to deliver on their campaign promises around public safety, with an approach marked by a lack of support from data, policy experts, or those most impacted. Last week, the council considered two new public safety bills, one addressing drug crimes and one sex trafficking, both of which would crack down in specific areas of the city and add new crimes to the city’s municipal code.

The Stay Out Drug Area law

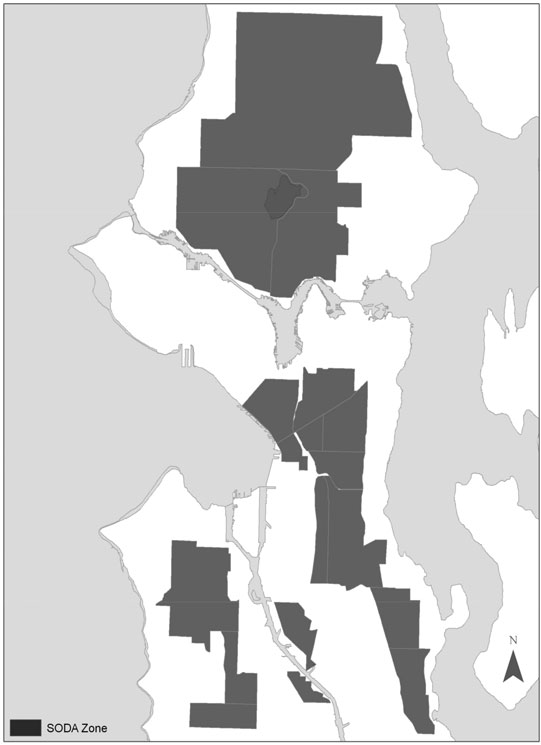

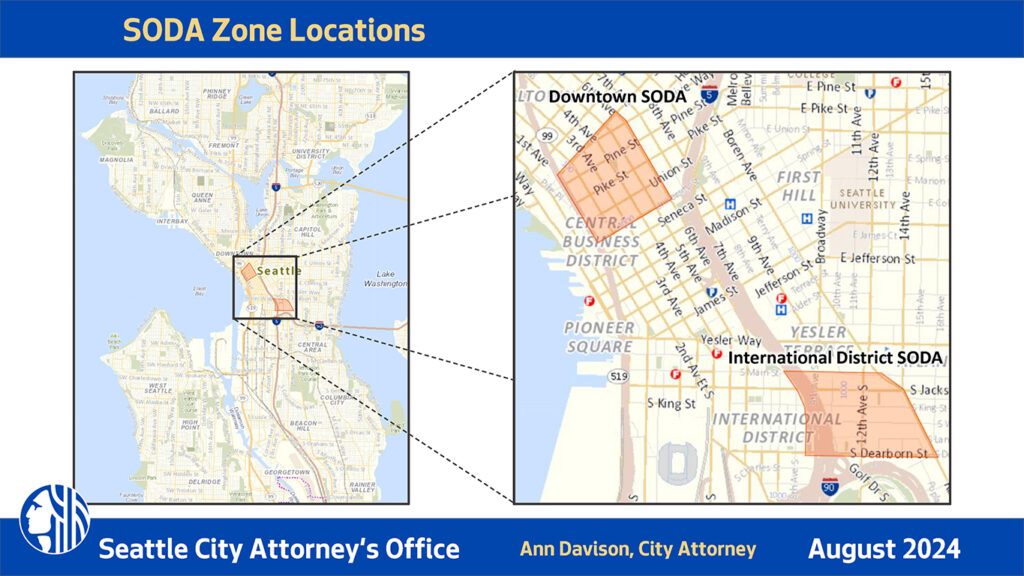

Seattle City Attorney Ann Davison has proposed legislation that would create Stay Out of Drug Area (SODA) zones. Under this new law, the Seattle Municipal Court (SMC) could issue a stay out order to anyone who is either charged with or convicted of a drug-related crime in a SODA zone, which include or a bevy of other crimes including assault, harassment, theft, criminal trespass, property destruction, or unlawful weapon use that a judge determines has a nexus with illegal drug activity.

The SODA order would ban people from entering two zones designated by Davison. One covers downtown, stretching from 1st Avenue to 6th Avenue between University and Stewart, and the other is a rectangle in the Chinatown-International District (CID) near the I-5 and I-90 interchange, including the intersection of 12th and Jackson.

If a person under a SODA order is caught in one of the two zones, they can be charged with a gross misdemeanor, which is punishable by up to a year in prison and/or a $5,000 fine. And because someone can be put under a SODA order when first charged, that means they can be arrested for this offense without ever having been found guilty of any drug crime.

Certain exceptions have been carved out of the SODA legislation, allowing those under SODA orders to continue to ride public transit, meet with legal counsel, and attend court hearings within the zones. Davison has said care was taken to craft the zones within a limited area accounting for just one quarter of one percent of the city’s nearly 84 square miles and allegedly not impacting people’s access to social services. However, some service providers do operate within the SODA zone, such as the Seattle Indian Health Board and We Deliver Care, PubilCola reported. Also within the zones are many affordable housing units, employment opportunities, medical offices, and religious institutions.

A SODA order could last for up to two years.

Davison said the purpose of this bill is “disruption to established drug markets in our city” and that this is the “least restrictive” action the city can take.

The SOAP prostitution loitering law

Councilmember Cathy Moore has also proposed legislation that would establish a similar Stay Out of Area of Prostitution (SOAP) zone in North Seattle, stretching from N 85th Street to N 145th Street a few blocks in either direction around Aurora. The legislation would reinstate a prostitution loitering law that was unanimously repealed by the city council in 2020. It would also create two new gross misdemeanor crimes: one for entering the SOAP zone when under a SOAP order and one for promoting loitering for the purpose of prostitution, which could apply to sex traffickers, but also to friends and families of sex workers who are simply giving them a ride.

Many services utilized by sex trafficking victims and sex workers lie within the SOAP zone, as does affordable housing, medical offices, and countless places of employment and services. There are no explicit exceptions to allow those placed under SOAP orders to access the places they need to continue their daily lives.

Moore said, “We cannot continue to have this level of gun violence in our city, nor can we continue to have this level of sexual exploitation of human beings on our street corners.”

She emphasized this bill would specifically focus enforcement on buyers and pimps rather than victims, while stating that diversion services are preferred for sex workers themselves. She also called out the program to vacate prostitution-related convictions from their records.

This has been tried before

This is not the first time Seattle has tried drug and prostitution loitering laws and exclusion zones. Hardline Seattle City Attorney Mark Sidran attempted to enforce much broader drug exclusion zones during his tenure in the 1990s and early 2000s. Subsequent city attorneys tended to place more emphasis on diversion and rehabilitative services, though loitering laws remained on the books.

The city council repealed both the prostitution loitering law and the drug loitering law back in 2020 per the recommendations of the Seattle Reentry Work Group, a body originally convened by then-Councilmember Bruce Harrell. The work group issued a report in 2018 with many such recommendations. Then-Councilmembers Alex Pedersen, Andrew Lewis, and Tammy Morales co-sponsored the repeal during the George Floyd protests in the summer of 2020.

At the time, Lewis told KUOW, “These laws were never appropriate. They were wrong when they were enacted and they’re wrong now.”

About the repeal of the prostitution loitering law, Pedersen said, ““I’ve committed to preventing disproportionate impacts on communities of color by police interactions and this is just one fix to our city laws.”

Emi Komoya, an advocate with the Coalition for Rights & Safety for People in the Sex Trade, said the repeal of the prostitution loitering ordinance was “one of the most concrete accomplishments of the [George Floyd] uprising.” She explained that advocates had been working for its repeal for several years before 2020.

At the time of the repeal, the City Attorney’s Office, then helmed by City Attorney Pete Holmes, had already largely stopped prosecuting such cases.

The Seattle Police Department (SPD) had attempted to enforce an expansive drug exclusion 20 years ago, before ultimately abandoning the policy.

In 2015 and 2016, Seattle tried a downtown drug crime enforcement crackdown called the “9 ½ Block Strategy,” which The Seattle Times reported resulted in drug-related calls to the police dropping within the emphasis zone while “calls increased in each of seven neighborhoods surrounding the zone during the strategy’s first eight months.” This finding raised questions as to how much zone-based strategies simply resulted in displacement of criminal activity to nearby areas. Since the nine and a half blocks emphasized a decade ago fall within the same zone targeted by Moore’s SODA legislation, the same pattern emerging would hardly be surprising.

At public comment on Tuesday, Gordon Hill, the deputy director of the King County Department of Public Defense, said of the proposed SOAP ordinance, “We know that this ordinance will fail. It’s failed before, It’s failed across the nation. Studies show it fails.”

Hill went on to say, “We know that this ordinance will make lives for those engaged in sex work more dangerous. it will push them into the shadows. it will make them more likely to become the victims of violence of customers, of pimps, of the trade that they work in.”

A study on exclusion zones published by Oxford University Press in 2009 concluded they were counterproductive: “[The researchers] demonstrate that, although the practice allows police and public officials to appear responsive to concerns about urban disorder, it is a highly questionable policy—it is expensive, does not reduce crime, and does not address the underlying conditions that generate urban poverty. Moreover, interviews with the banished themselves reveal that exclusion makes their lives and their path to self-sufficiency immeasurably more difficult.”

The ACLU opposes both bills proposed in Seattle.

Other problems with the bills

Besides the obvious problem that similar policies have failed in the past, these bills have many other issues.

The SODA drug zone bill doubles down on the city’s new War on Drugs, in spite of data showing that people who are incarcerated for drug use are much more likely to overdose and potentially die by overdose upon their release. Experts also agree criminalization of drug use is not effective for treating substance abuse disorder.

Last year’s ordinance criminalizing public drug use also means that the lauded Law Enforce-Assisted Diversion (LEAD) program can no longer accept referrals from anyone but SPD due to capacity issues.

The SODA bill would make it much easier for the City Attorney’s office to criminalize poverty and substance abuse disorder. As it stands now, when someone is arrested for public drug use, their drug use must be proven in court. This requires sending samples to the Washington State Patrol Crime Laboratory, which is currently backed up. But if someone is put under a SODA order, they can later be arrested for violating that order, and their drug use never has to be proven in order for them to be convicted of a gross misdemeanor.

“As someone who has represented indigent clients for years, this law isn’t going to help anyone except to allow the downtown shoppers and retailers to avoid the suffering in our community,” Katie Hurley, special counsel for criminal practice and policy at the King County Department of Public Defense, testified.

Meanwhile, the SOAP prostitution bill doesn’t follow best practices for fighting sex trafficking, which emphasize the importance of avoiding retraumatization of victims. In order to provide trauma-informed care, victims are supposed to be given time to consider options and have agency over their own decisions while not enforcing power dynamics, something that reinstating the misdemeanor for prostitution loitering will not achieve.

In response, 30 organizations advocating for the rights of sex workers, the LGBTQ+ community, and the homeless signed a letter opposing this legislation, stating they “are concerned that the proposed prostitution loitering legislation will only serve to criminalize survivors and create barriers to much needed support rather than increase safety.”

While the bill does state that diversion is preferred for sex workers and trafficking victims, advocates say diversion programs and services are already at capacity, and at present, the bill doesn’t include any funding to expand them. They also say that the prostitution loitering misdemeanor isn’t necessary for survivors to receive these services.

“We have outreach people… and they’re a lot more cost effective, and they don’t have this hostile relationship,” Komoya said.

“As long as you see the police as outreach, the police to be the ones to offer referrals and resources, then they’ll come to the conclusion that they need to have power, right?” Komoya continued. “But it’s not because the outreach requires power. It’s to address the fact that police can’t have a genuine relationship with the community that outreach workers can.”

“If one’s intentions are to not arrest victims and survivors and people who are perceived as being prostitutes or doing sex work or being trafficked, I think there’s a very real difference between that intention and what the actual impact of the bill will be,” said Amarinthia Torres, the co-executive director of policy at the Coalition Ending Gender-Based Violence.

Mary Williams, a sex trafficking survivor expert and substance use disorder professional, agreed that the bill wouldn’t have the intended effect. “I think there’s other issues at play,” she said.

Williams pointed out that the groups most often targeted for sexual trafficking are those already at the margins. “We talk about the groups that are really targeted, and it’s people who already have a lot of challenges, you know, like the challenge of being a foster kid or being in poverty or being homeless, being disproportionately chosen because you’re a woman or LGBTQ person.”

Potential victims are also more likely to be targeted due to their racial identities.

In spite of the known racial disparities, no racial equity toolkit was done for either the drug or prostitution bills. Instead, the SOAP bill directs SPD to do annual reporting identifying racial disparities after the fact. The Office of the Inspector General would also be asked to do some reporting, but the first report wouldn’t be due until mid-2026.

The Central Staff memo on the SODA bill says, “Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) individuals are disproportionately charged with, and convicted of, the crimes for which CB 120835 would allow a judge to issue a SODA order.” The memo stopped short of explicitly calling for a racial equity toolkit, while alluding to that racially disparate impact.

SPD has a documented history of detaining Black and Indigenous people at much higher rates than White people, and more than one out of every 20 Terry stops performed by SPD was found to be unconstitutional by the court monitor appointed by the federal government. Some advocates worry that the SODA and SOAP zones will encourage more stop and frisk tactics by police, which run the danger of being both unconstitutional and disproportionately impacting marginalized communities.

Both Komoya and Torres brought up their concerns about the lack of a racial equity toolkit for these two bills.

Torres and Audrey Baedke, the director of partnerships and training at Real Escape from the Sex Trade (REST), emphasized that there aren’t currently enough services available for sex trafficking survivors.

“The one thing that all survivors that I’ve talked with have agreed on is that more services are needed,” said Baedke.

Baedke said one study found 90% of women would leave sex trafficking if they had a viable option. Right now, REST operates the only emergency shelter for sex workers in the city, which provides seven beds at a cost of $650,000 per year. Baedke says that ideally they’d have twice that amount of funding so they could open a new shelter and provide another seven beds.

“The concern that we have is that those services are chronically, inadequately unfunded, underfunded, and we don’t have enough resources and support to offer those programs,” said Torres. “And many programs are barely staying open. They have a hard time retaining staff because of overwhelming workloads and staffing shortages. They’re not able to meet the needs that we know survivors have because of capacity constraints.”

Williams suggested using one of the new crisis centers funded by the King County levy to provide more services to sex trafficking victims to help bridge this gap.

Reinstating prostitution loitering as a crime can also put sex trafficking victims at greater risk from the police officers themselves.

Baedke talked about past incidents where police who brought women to REST to get services would touch the women inappropriately and otherwise sexually abuse them during transit. “I’ve heard countless survivors say that they’ve had buyers who are police officers, and so police officers are going to be the ones who are enforcing this,” Baedke said.

“Anytime you have power imbalances and you have positional authority in the mix, there is always a risk for gender-based violence and abuses of power to occur, and I think that is something that we have to really look at with this bill,” Torres said.

Former City Attorney Pete Holmes did not mince words when he told The Stranger this law would be like giving police officers a “hunting license” for prostitutes.

The SOAP legislation also asks the Human Services Department to look into creating a program to help sex workers arrested under the law remove the arrest from their record. However, this program doesn’t yet have any allocated funding, and advocates are skeptical as to its utility.

“It’s a kind gesture,” Baedke said. “In actuality, no, it’s not practical, because, again, if somebody has a trafficker, that trafficker is not going to let them do the process to have this removed.”

Both she and Torres spoke about the long amount of time needed to expunge a criminal record, which can often take three years or more. “That’s a long time to ask survivors to […] wait and to still be experiencing all the barriers,” said Torres.

City council’s desperation is showing

After largely being elected on public safety promises, the new city council seems desperate to show they’re accomplishing something, especially in the wake of criticism that they’ve passed little substantial legislation during their terms thus far.

At the public safety meeting last week, public commenters supporting the SODA and SOAP bills were widely concerned about activities like gun violence and the trafficking of minors that are already illegal and that SPD officers could already be addressing.

While safety concerns should be taken seriously, neither bill will change SPD’s performance when it comes to violent crime or solve SPD’s staffing issues; nor will they create more capacity at the municipal court to hear cases, or more beds at the understaffed King County Jail. Even the 20 to 30 beds that will be available through the new pilot program with the SCORE jail in Des Moines will hardly make a dent in any strategy to deal with homelessness, drug use, and sex work primarily through arrest.

Neither bill meaningfully addresses the root causes of gun violence, substance abuse disorder, and sex trafficking in our community. No additional funding for support or services is being offered at this time. Moore said she’d be asking for money in next year’s budget for an emergency receiving center for sex trafficking survivors, although she hasn’t yet identified a specific funding source in a year in which the city is anticipating more than a $260 million budget deficit.

At present, these bills represent unfunded mandates that allow the council to appear to be “doing something” while not having to spend much, if any, money.

In an unusual move, Moore asked for revisions to the Central Staff’s prepared memo on the SOAP bill, replacing the original memo with one that was more favorable to her bill. Sections removed from the memo included concerns about the bill not providing additional funds for diversion or other services, and the risk it could result in SPD arresting a disproportionate number of sex buyers who are people of color.

Due to Moore’s pushback, Central Staff revised both memos to exclude a line saying the bills could be seen as a missed opportunity to understand the root causes of drug use and sex work.

Even interim SPD Chief Sue Rahr told the Stranger, “We don’t have a system in place to make that happen,” speaking of getting treatment for those with substance abuse disorder. And she said she’s not “well-versed” with the different organizations that the SOAP bill would be relying on to provide services to the sex workers her officers would be potentially arresting with a preference for diversion.

Rather than presenting a rigorous case for why the exclusion zone approach would be effective policy, councilmembers increasingly leaned on rhetoric, saying that the initiative would be better than doing nothing.

Council President Sara Nelson said, “We have to do something. We cannot not do anything more. No amount of throwing more money at the problem is going to make a difference.”

“We are simply not going to arrest our way out of these challenges. Facts,” Councilmember Rob Saka said. “But colleagues, I’ll be perfectly honest here with you, we’re not going to kumbaya only our way out of this. We need more tools. […] We need to do something.”

“We don’t have a perfect solution,” Moore added. She said she is open to improving the bill.

Moore has since said she wants to propose an amendment that would limit the SOAP ban zones to buyers and promoters and not have them apply to the sex workers themselves.

The public safety committee will be discussing these bills again, as well as possible amendments, at their next meeting on September 10.

“I do believe that victims and survivors deserve better. They deserve to be able to not be further criminalized by harmful bills. And we deserve solutions and support that survivors can count on,” Torres said. “Without those meaningful solutions, we’re not actually going to address anything about the root causes of gender-based violence or any of the problems that folks are hoping to solve that we all care about, about violence happening in our communities.”

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.