King County Executive Dow Constantine’s vision for a transformed “civic campus” around the iconic County Courthouse and other county-owned properties in Downtown Seattle became much more clear late last week, as his administration released a new strategic plan for the undertaking. The plan spells out how King County might redevelop not only the eight buildings it owns near Pioneer Square, but also the 24.5 acres of land currently home to Metro’s Atlantic and Central bus bases in SoDo, moving some of the administrative and criminal justice functions the county oversees out from the urban core.

The ultimate goal? A “24-hour neighborhood” with significantly more residential and office space than exists today, but with the additional intention of activating ground floor uses by creating a significant amount of new civic space in addition to bringing in retail amenities. But even with the 340-page plan released this month, there are still many unanswered questions around how the county might implement this incredibly bold vision. For example, could a condensed Metro bus base still support plans for expanded service?

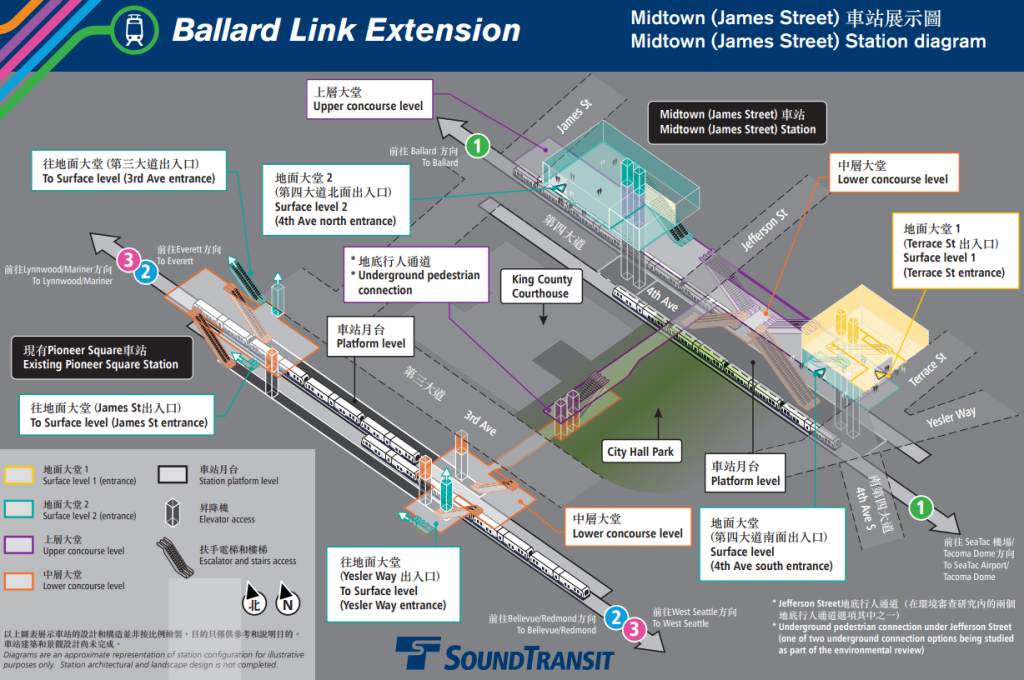

The future of South Downtown is inextricably linked with a potential alignment for Sound Transit’s Ballard Link Extension project, with the board’s current “preferred alternative” set to plop a station down right in the middle of King County’s holdings in the neighborhood. Constantine has touted this location as a golden opportunity for the county and the neighborhood as a whole, but many transit advocates see the choice not to site the station at the region’s biggest transit hub along Jackson Street as a generational mistake. With a final decision months away, the plans are still very much up-in-the-air.

While prior to this report’s release, the county’s plan for what it wanted to do with its holdings seemed more vision than roadmap, the information contained in it spells out a dramatic proposal that would reshape vast swaths of Seattle’s urban core. If achieved, it would certainly represent one of the boldest urban transformations that a U.S. city has seen in decades.

Reinvigorating a forgotten corner of Downtown Seattle

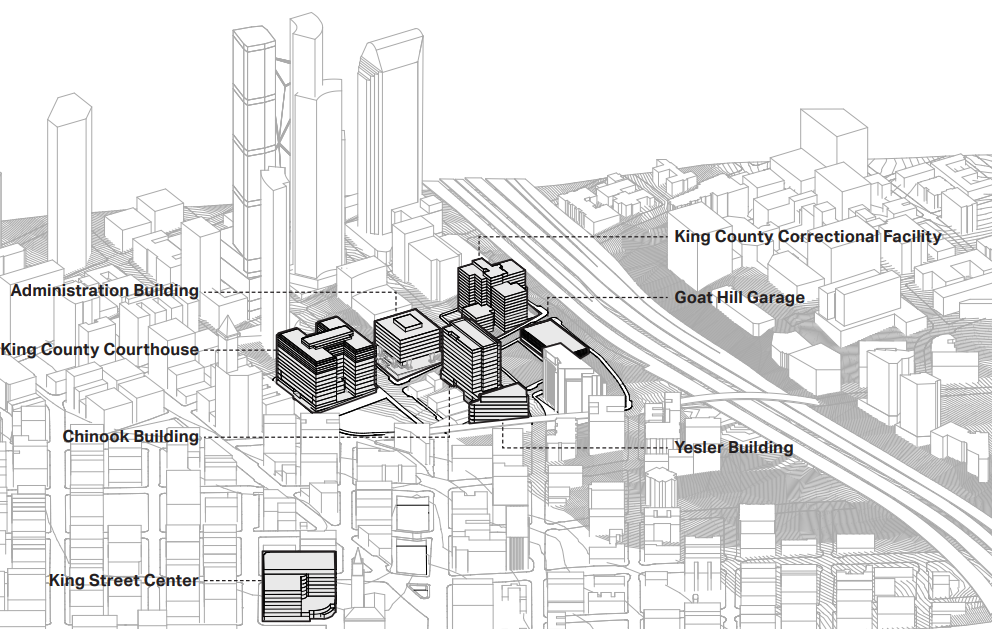

At the centerpiece of the plan are the eight county-owned buildings clustered around the King County Courthouse between Yesler Way and James Street, including the courthouse itself, the now-vacant Administration Building, the King County Correctional Facility, the Goat Hill Garage, and two more office buildings: the historic 1909 Yesler Building and the 2007 Chinook Building. The county also occupies most of the office space in the King Street Center building several blocks away, and is set to fully own that building by 2027.

“The county government’s current home base is spread out across eight blocks in the urban core that constitute some of the most desirable real estate in the region, but the area is stagnant,” the strategic plan notes. “This historic area, nestled between Pioneer Square, the Chinatown International District, the Central Business District, SODO, and Yesler Terrace, can remain the center of our local government, but it can also be so much more.”

The plan paints the costs that the county would have to incur to upgrade all of these facilities as astronomical: close to $700 million to maintain a state of good repair on all buildings, including $264 million for the King County Courthouse and $118 for the King County Correctional Facility. But those repairs are also said to “perpetuate existing functional deficiencies” that hinder the county from effectively providing services. The courthouse building itself, it says, has reached the point of “functional obsolescence.”

The same goes for the correctional facility. “The current facility is part of a prison lineage that can be traced back to the direct supervision models of the late 1700s, and the prison warehousing models prevalent in the early 1980s,” it notes. “The current correctional facility was completed 38 years ago, in 1986. Today, county staff and service providers are trying to meet the current needs of the populations they serve in a building designed to fit 40-year-old jail programming that was modeled on 200-year-old ideas of punitive detention.”

But there’s another big reason the plan concludes that doing nothing is not an option: Sound Transit. “Future regional transit work may radically alter the landscape on the county’s existing downtown Seattle campus, demolishing county-owned buildings and severing critical functional ties between the courts and correctional facilities,” the plan notes. “Even if over $700 million were spent over the next 20 years to repair and maintain buildings, or even if $2.5 billion to $3.2 billion was spent to overhaul current buildings, impending transit improvements may fundamentally alter existing conditions, demanding a new scenario for the future of King County facilities.”

The Sound Transit Board of Directors has not yet voted to finalize an alignment for Ballard Link that would site a station where the County Administration building stands today, though the option is the preferred alternative. Costs to build the option preferred by transit advocates, near the existing Chinatown-International District station on Jackson, would be combined with costs that come from changing the preferred pick and delaying the project. But the report paints the station’s impending location as an outside force, when it was Constantine himself who has become one of its biggest proponents, along with Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell.

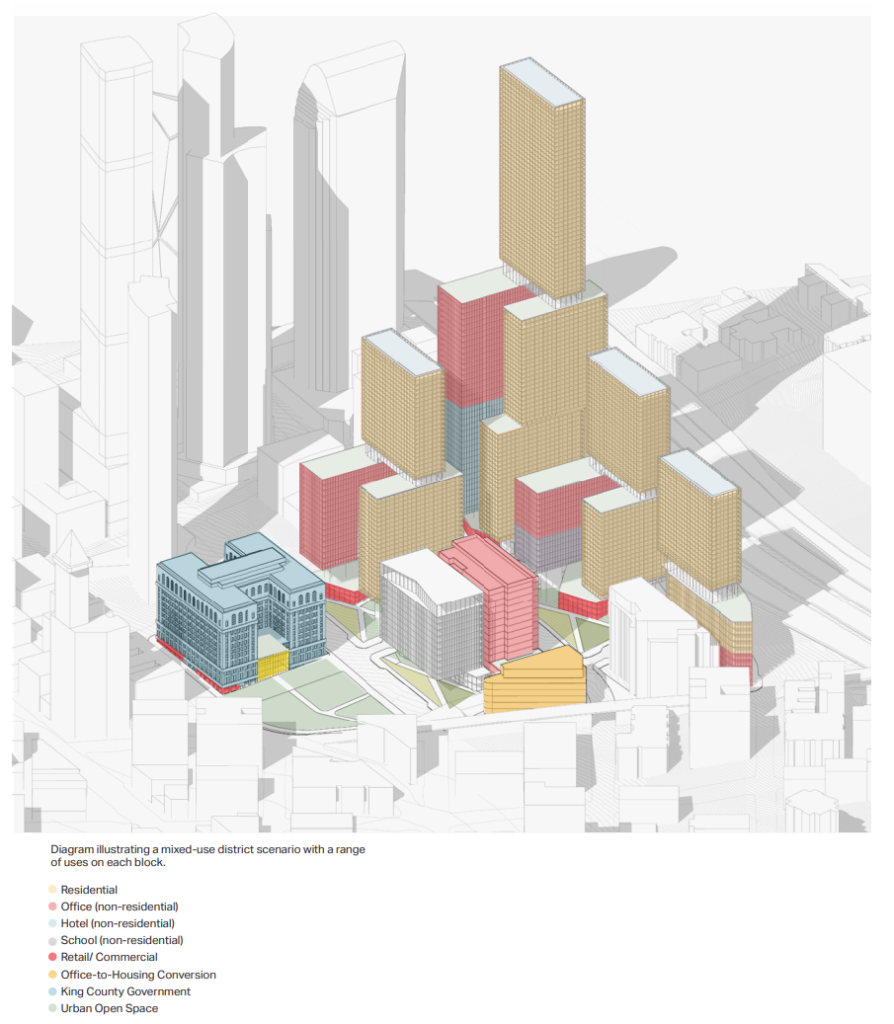

With the need for redevelopment painted as inevitable, the plan includes an ambitious proposal to completely reinvent the three-and-half blocks that are home to the Administration Building, the Correctional Facility, and the Goat Hill garage. “The order of magnitude of potential development across these five parcels is staggering,” the report states. The Chinook Building, Yesler Building, and King Street Center could continue to see county use, or be leveraged via sale or lease to fund other elements of the county’s plan.

Civic campus could see up to 7,800 new homes built

In the end, the county sees a path to unlocking an immense potential for both new office space and housing on a corner of downtown that’s incredibly underutilized.

“Seattle is one of the fastest growing cities in the country, yet there is virtually no housing in this part of the city,” the plan notes as it inches closer to real estate brochure than county strategic plan. “Redevelopment needs to include a range of affordable and market rate housing that support a wide variety of household sizes; it should make room for affordable retail and commercial spaces at ground level to foster a vibrant environment of diverse local businesses, and the area should be planned to create a coherent ground-level arrangement of spaces across the entire district that promote public life.”

With the ground floor levels of the parcels reserved for civic uses, the report concludes that the county’s parcels could be redeveloped to add hundreds of thousands of square feet of retail and office space, and around 5,000 units of housing under the current zoning. With a zoning change, that could increase to just under 8,000 units of housing. The report includes a desire to change the “development paradigm,” moving away from traditional building podiums and instead “shifting the premise of the ground plane from a space for private profit to a space of public purpose.”

Not everything would be completely rebuilt from scratch. Under the plan, the landmark King County Courthouse would remain after a substantive overhaul. The vision for the remade building would see its orientation pivot to City Hall Park to the south, expanding the park space with more ground floor amenities that tie it in with the rest of downtown. There’s also the possibility of constructing additional stories above the courthouse building, something that would fit with the history of the building, originally constructed at five stories in 1916 with another five added in 1929.

A new civic campus in SoDo

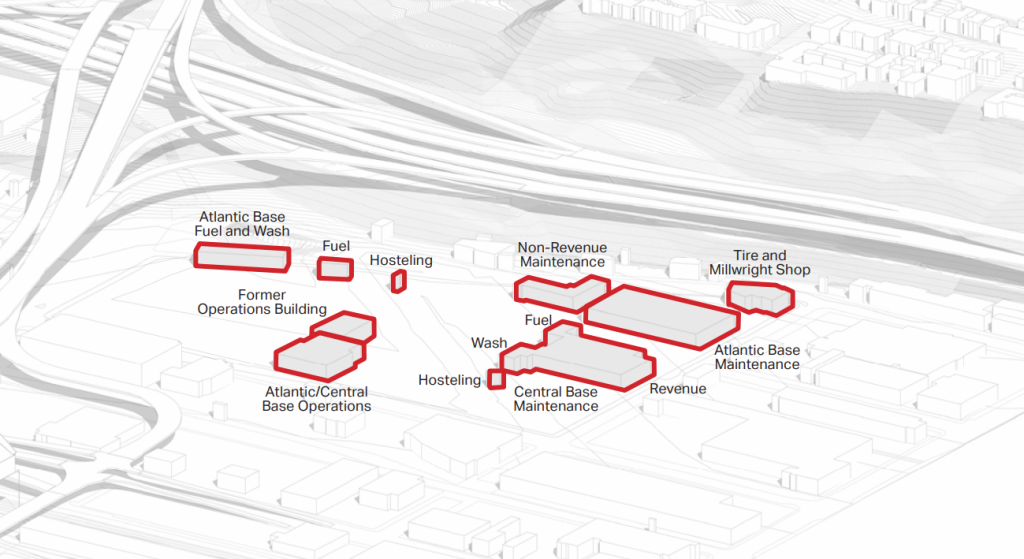

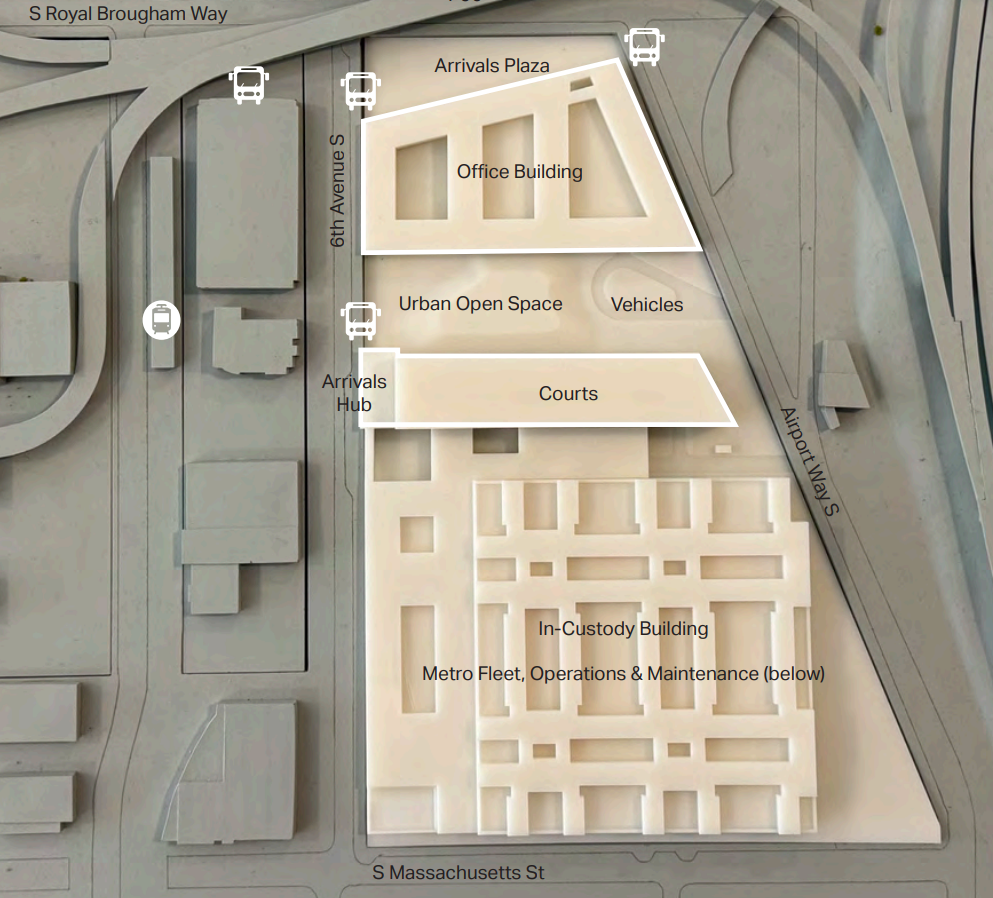

The County’s plan to redevelop the existing jail facility and many of its downtown offices depends on a plan to find a second site for many of those uses, and the plan details how the 25-acre King County Metro bus base in SoDo would be that site. With many of Metro’s essential needs on the base spread out across the entire parcel, with the rest occupied by surface parking, the county would create a more compact Metro facility while still allowing the state’s largest transit agency to operate from this essential spot close to Downtown Seattle.

“The SODO site illustrates a rare opportunity for a municipal government to transform facilities by moving functions to a more opportune site, while remaining in essentially the same area,” the report notes. “The redevelopment strategy also envisions new structured facilities for Metro fleet and operations, to protect county assets from constant exposure, to accommodate new fleet technologies, and to facilitate Metro employees’ ability to efficiently and enjoyably conduct their work.”

With space freed up by shifting Metro’s operations to be more vertical, new buildings devoted to courts and other county offices would be constructed on the SoDo site. There would also be space for a new correctional facility modeled on a more restorative model of justice. “To depart from typical U.S. models of punitive detention, the proposed facility has been benchmarked against Halden Prison in Norway, which has served as a model facility across a number of aspects related to detention and treatment,” the plan states.

Many questions remain about how a new Metro bus base, integrated vertically with other county functions, will work over the long term and support bus service expansion aspirations, in alignment with the agency’s Metro Connects plan. The county points to the Protrero Yard redevelopment project in San Francisco, but there are significant differences between the projects, with Protrero Yard only one block in size in the middle of an urban neighborhood.

According to the plan, “[f]uture coordination between King County agencies and departments is essential to merging the goals for proposed county facilities with existing transit agency timelines.” Atlantic is the only bus base that serves Metro’s fleet of trolleybuses, the workhorses of the fleet that have been running on electric power for 84 years, but are largely being left to the side when it comes to conversations around fleet electrification.

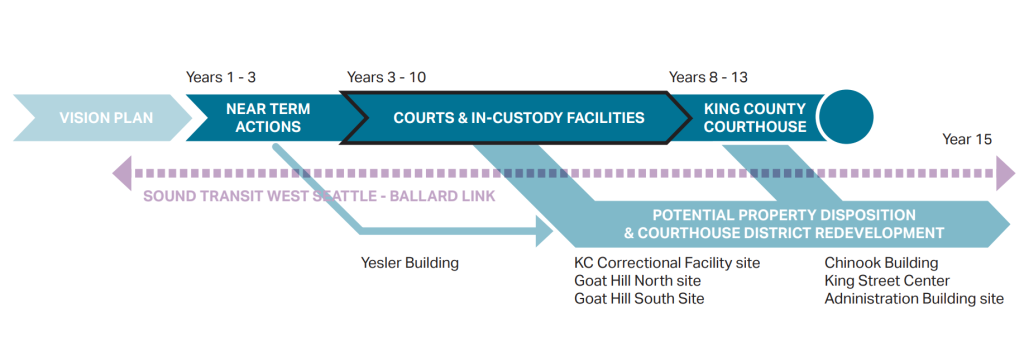

A 15-Year Timeline of Redevelopment

The plan’s release gives the public, for the first time, an idea of what redeveloping the entire civic campus would look like, walking through what would happen in every year of a 15-year development timeline. Because Metro’s bus base is not sitting unutilized, creating new bus maintenance and storage facilities would have to happen first for the biggest changes to be able to move forward. Construction on new Metro facilities would happen by year five, two years before Sound Transit begins construction in earnest. One-off redevelopment projects, like the conversion of the Yesler Building into residential or other uses, could happen independently.

Once a new court and correctional facilities are complete in SoDo, expected in year 10, the county can start to redevelop some of the biggest parcels in its portfolio. “New courts and in-custody facilities are important for the county’s ability to continue providing high-quality services,” the plan states. “The completion of proposed courts and in-custody facilities are also critical to unlocking redevelopment potential on a series of downtown campus properties, including the King County Courthouse, the King County Correctional Facility site, and the Goat Hill North site.”

Ultimately, the plan is not a contract, and it notes a need to remain flexible. Clearly one of the biggest driving forces guiding the work will be the economic realities that the county faces like any other government entity.

“Outlining a vision for future county facilities is an important first step in addressing the county’s facility needs. However, the ability to maintain flexibility within that vision, particularly over time, is equally important,” the report states. “Flexibility in physical planning allows the county to navigate unforeseen challenges, seize new opportunities, respond to community needs, and ensure that the strategic direction remains relevant and effective.”

But it’s unavoidable that the vision presented by the strategic plan would represent a bold transformation of Seattle’s urban core and includes a lot of elements that would make Downtown Seattle more vibrant and allow more people to live close to the region’s transit investments. Whether that vision will be able to be translated into reality is the big question that remains.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.