Over the past few months, Seattle City Councilmember Bob Kettle has expressed doubts about pursuing street redesigns aimed at reducing crashes, because those improvements could have a detrimental impact on the ability of first responders to get to emergencies as quickly as possible. The comments, made both at the Seattle City Council and at regional planning bodies, fly in the face of best practices in transportation engineering and have not been backed up by any specific evidence that emergency responses are being impeded in Seattle or elsewhere by street upgrades like protected bike lanes or rechannelizations that narrow or reduce car lanes, colloquially known as “road diets.”

Kettle made his latest set of comments last week at the Puget Sound Regional Council’s (PSRC’s) executive board meeting, as that body was preparing to approve sending hundreds of millions of dollars in federal grants to cities and counties around the region. Many of those projects will improve pedestrian and bike infrastructure, and throughout the project selection process, PSRC staff have been emphasizing how many projects are including proven safety countermeasures as defined by the Federal Highway Administration (FHWA).

“One of the things that we learn as I engage with the various [police] precincts, but really importantly the fire stations, is that as we push to make our roads safer, and we brought in these different pieces, like bike lanes and the like, we need to be mindful of the impacts on our first responders,” Kettle said. “If you haven’t been to the fire stations and talk to the firefighters and their leadership teams, these fire engines, these ladder trucks, cannot maneuver in very tight spaces and sometimes the road diets, or the bike lane, the curbs that we now have here in Seattle, can make it very difficult for the fire engine, the ladder trucks, to get where they need to get, and if first responders can’t get to where they need to be, and then have that person taken to Harborview, [or] whatever other place, that creates a safety problem in of itself.”

Kettle did not provide any specific examples of projects in Seattle that had shown to impact emergency response times. The projects in Seattle on the PSRC list approved by the board included Harrison Street transit improvements, station improvements around the coming West Seattle Link extension, additional funding for Aurora Avenue safety improvements, and funds for Sound Transit’s infill light rail station at Graham Street in the Rainier Valley. Given the lack of detail, it wasn’t clear if Kettle’s had any of these projects in mind.

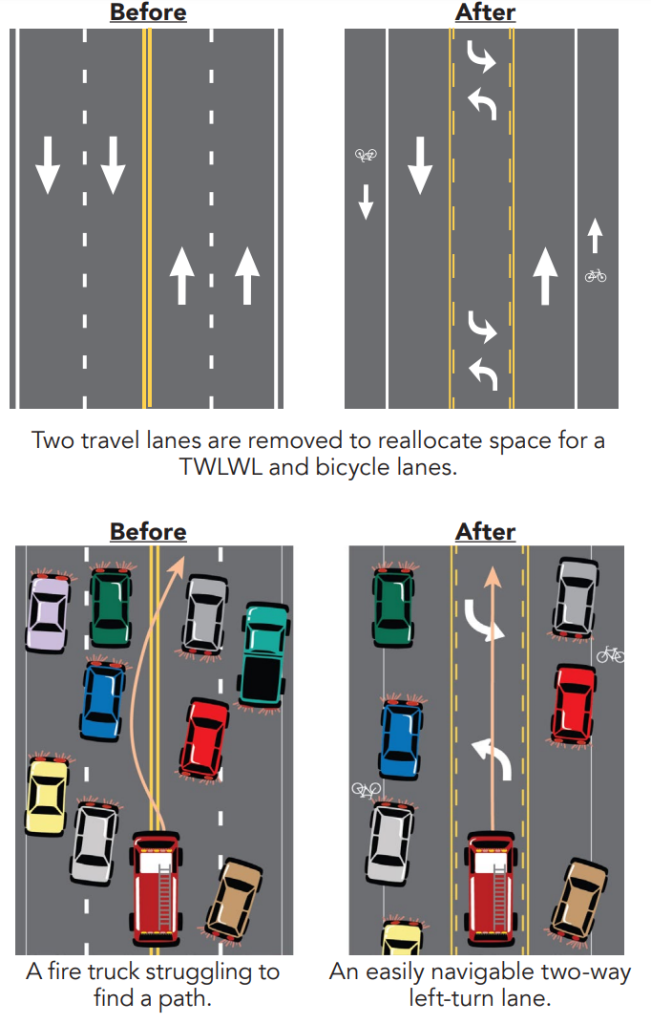

The discussion comes on the heels of a new peer-reviewed study looking at the impact of 4-to-3 “road diets” in Cedar Rapids and Des Moines, Iowa. It found that converting a formerly four-lane road to a two-lane road with a center turn lane resulted in “no difference in emergency response rates.” Perhaps more tellingly when it comes to Kettle, and his conversations at Seattle’s fire stations, the study found that 40% of the first responders asked about their perception of the roadway improvements stated that they thought it had a negative impact when it had not.

The finding that road diets do not generally impact emergency responses is not new. The FHWA has made it clear to cities that 4-to-3 road diets do not negatively impact emergency responses, including the claim on a set of “road diet myths” in 2016. “Contrary to popular belief, Road Diets do not degrade response times for law enforcement or emergency responses,” the agency’s fact sheet noted. In fact, FHWA stated, 4-to-3 upgrades can actually improve response times by providing that dedicated turn lane that can be used by emergency vehicles.

Kettle, along with the majority of his colleagues, voted against Councilmember Tammy Morale’s amendment seeking to boost the levy’s size by $150 million, mostly to fund safe streets upgrades.

While similar remarks that Kettle made on June 18 at the Seattle City Council’s select committee on the 2024 transportation levy went unchallenged, his comments at PSRC brought responses from other elected officials from around the region, including King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci. Two days earlier, Balducci had held a committee meeting on the Safe Systems approach and moved forward a motion to adopt that approach across King County government. The Safe Systems framework (or similarly-minded Vision Zero approach to eliminate fatal crashes) tends to de-emphasize spot enforcement and education campaigns and instead emphasize designing roads to be more forgiving of mistakes.

“In my city, when I was on the City Council, all of our permits for new bike lanes, roads, sidewalks, developments — everything — had to go through a permitting process that included a fire department review to make sure that we weren’t doing anything that wouldn’t allow fire trucks to get through,” Balducci said. “And many times, designs had to be changed to make sure that fire trucks had to get through. So I’m sure Seattle does that as well. We do not neglect to make sure that fire trucks can go where they need to go.”

In Balducci’s home city of Bellevue, a similar debate surfaced recently over the Bike Bellevue rapid implementation plan, after David Winokur, the chief administrative officer of Overlake Medical Center, wrote to the Bellevue Transportation Department in March in support of the plan. Just four days later, Winokur sent a follow-up email giving a caveat that while the hospital supports bike lanes, they don’t support reallocating space away from general purpose vehicles.

“As one of the community’s stewards of health and wellbeing, we cannot support an initiative that would potentially slow our city’s ambulance and fire response through the urban core,” Winokur wrote. “An alternative bike network through Downtown, Wilburton, and Bel-Red that does not take away road lanes is an approach that we would find sensible to further our collective cause.”

That response prompted Annemarie Dooley, a physician at Overlake Hospital who had initially been the one to prompt hospital administration to support Bike Bellevue, to respond at a recent meeting of the Bellevue City Council. Dooley said she went to talk to first responders, such as Dr. Michael Sayre, the medical director for Seattle Medic One, who told her that bike lanes were not an impediment.

“He has a lot of experience as head of Medic One with bike lanes that are already installed all over the Puget Sound, which is the reach of Medic One, and he was not concerned at all that bike lanes increase emergency response times,” Dooley said.

Ultimately, while the claim that changes to road design that make lanes more narrow and move curbs could impede emergency responses might seem intuitive to some, including many first responders themselves, the evidence just doesn’t seem to support that claim.

Asked for additional comment, Kettle told The Urbanist that he was not talking about ambulances, but only Seattle Fire Department ladder trucks. “I am speaking to the fire engines and the ladder trucks that are responding,” Kettle said. “I’m talking about impacts to fire engines and ladder trucks, which do respond to the medic calls, all the calls that fire gets. […] I have a history both in Queen Anne and here in terms of supporting Vision Zero and all the different pieces. I have said many times on the dais that I support the bike lanes like on 2nd and 4th, that is not what I was referring to.”

An SFD spokesperson seemed to offer a different perspective from Kettle, declining to cite any instances where the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) had hindered emergency responses with street improvements.

“The Seattle Fire Department works closely with the Seattle Department of Transportation on proposed projects and has a member designated to serve as a liaison to provide feedback,” SFD’s Kristin Hanson said. “Broadly, this position works collaboratively with SDOT and shares input on impacts to the fire department’s response to emergencies. We do not have a comment in regard to specific SDOT projects. As the first responder to the most serious collisions and traffic fatalities in Seattle, SFD supports the goal of SDOT’s Vision Zero work to reduce these incidents.”

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.