This March, when Seattle City Light took to social media to celebrate the groundbreaking of King County Metro’s first bus base solely dedicated to battery electric buses in Tukwila, many transit advocates raised an eyebrow at the wording of the post. “Have you seen an electric bus around Seattle? If not, you will!” the post read. It was an odd choice of wording because electric buses have been crisscrossing Seattle for 84 years, with electric trolleybuses taking over routes that had been served by the city’s streetcar and cable car networks in 1940.

Metro’s new Tukwila bus base is seen as a ground zero in its mandate to become an all-electric transit agency by 2035, a goal promoted and embraced by the top echelons of county leadership. But the idea that electric buses on Seattle streets are brand new illustrates the degree to which trolleybuses have faded into the background despite being the absolute workhorses of King County Metro network. The 14 routes that make up the trolley network, all of which run entirely within Seattle city limits, carried 19.5% of riders systemwide in 2023 while accounting for only 16% of the agency’s platform hours.

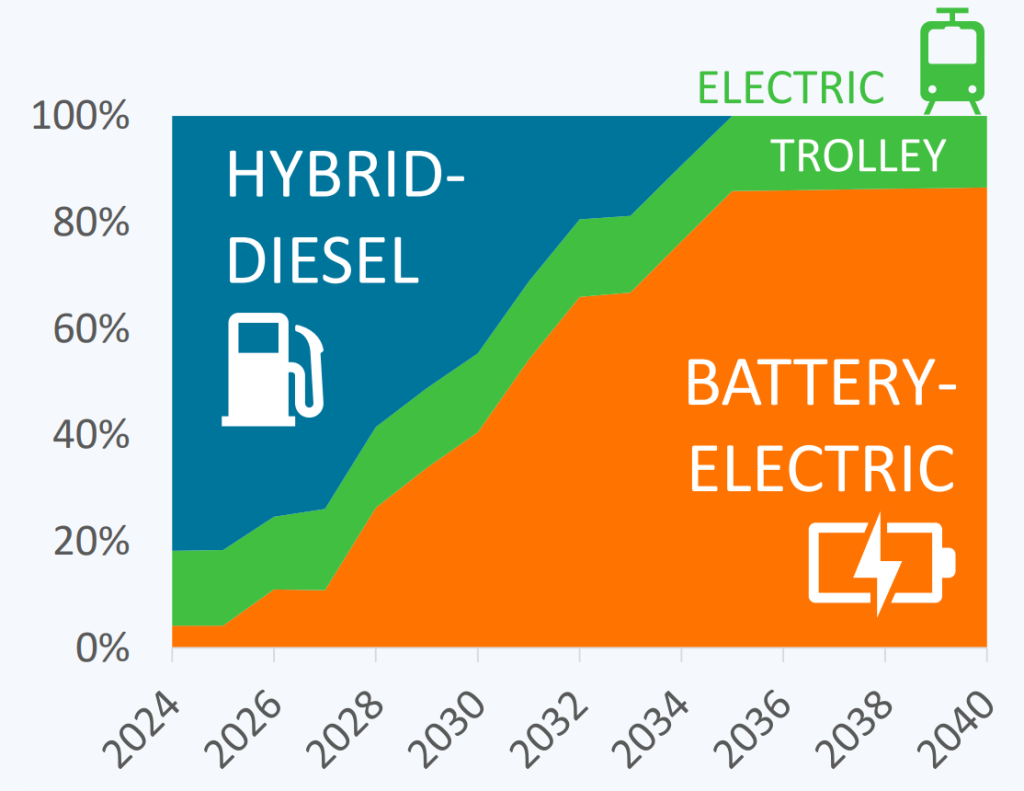

In June, the King County Auditor released a report digging into obstacle facing Metro’s electric vehicle transition. The report noted “significant risks that may impede reaching the goal” and spelled out some significant headwinds that Metro will face if it tries to convert its entire fleet to battery-electric buses as fast as possible. Those risks include a bus market in the US with a dwindling number of manufacturers, and the fact that battery-electric buses don’t currently perform as well as diesel-hybrid buses.

“In Metro Transit’s experience, hardware and software technology to support base operations and fleet charging capacity is developing but does not work reliably yet,” the report noted. Due to those limitations on battery technology, Metro is exploring options with fewer potential environmental benefits like hydrogen buses, without even discussing that change in strategy with the King County Council, according to the auditor’s report.

While trolley technology will likely not be a solution that can scale across the entire county without overcoming some significant hurdles, the auditor’s report treats the idea of trolley expansion as little more than a footnote. “[Metro’s] fleet plan includes potential for trolley expansion in 2027, but these plans are still preliminary,” it notes.

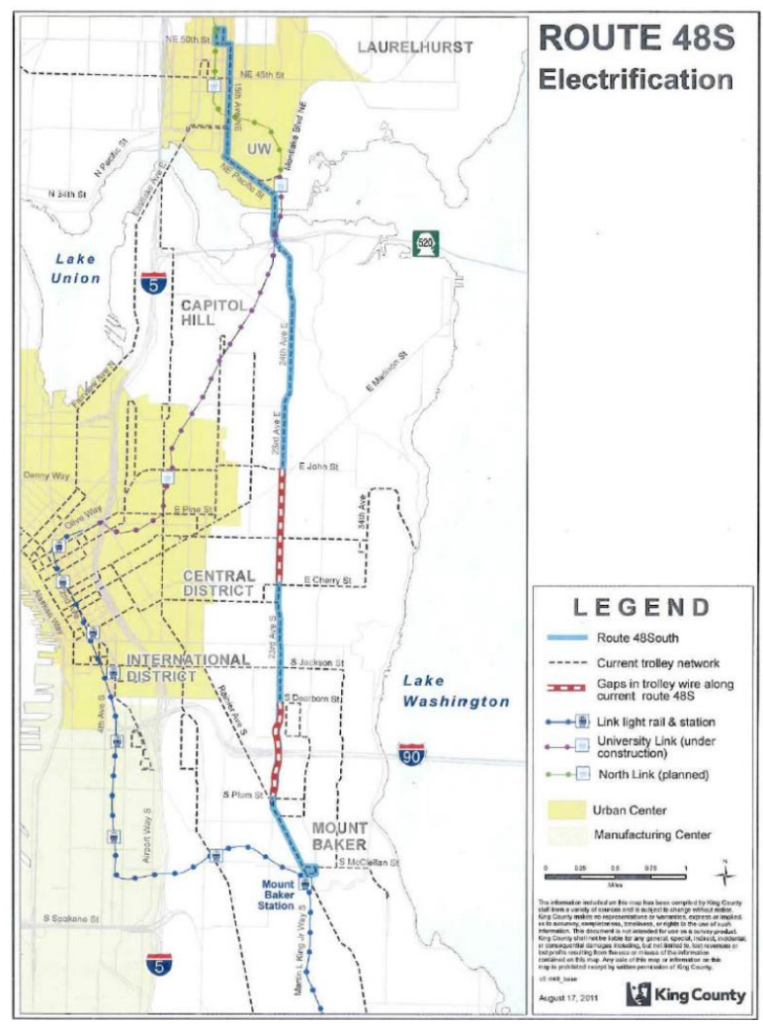

The relative neglect of the trolley network is epitomized by the Route 48: a frequent route that has run underneath the trolley wires used by other routes for decades, with just two stretches that would need to be filled in for the route to be able to become fully electric. In 2014, the City of Seattle completed a study that looked at whether turning the 48 into a trolley made sense from a business perspective for Metro. The answer was a clear yes, even just looking at the projected costs of diesel under most scenarios, but with the environmental benefits along with noise and air quality benefits, it was a slam dunk.

When the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) rebuilt 23rd Avenue through the Central District in the mid-2010s, the project added poles that were intended to hold up trolley wire, a first step for Metro to be able to more easily come back and complete the full Route 48 electrification project. But a full decade after the initial study was completed, the 48 still is not a trolley route, and this week a Metro spokesperson confirmed that construction on the upgrades isn’t set to start until 2027. Metro’s Jeff Switzer blamed the pandemic for a project that likely should have been completed long before that.

“The Route 48 Trolley project was delayed because King County experienced a budget gap in 2020 due to the economic effects of the pandemic,” Switzer told The Urbanist. “This required Metro to re-prioritize capital projects based on funding and resources available. That meant projects closer to implementation received priority over projects still in development. Staffing constraints agency-wide (and nationally at most transit agencies) have also been a factor in project delays.”

This fall, Metro will open the RapidRide G Line along Madison Street. Due to the fact that the buses serving the G Line need to have doors on both sides of the coach, Metro was not able to procure trolleybuses for the route from any manufacturer and the 13 vehicles serving the route will be diesel-hybrids, replacing the existing trolley service through First Hill. The Route 12, which currently serves Madison and is moving to E Pine Street, will return to trolley service within a few years when a final gap along that street is added. With eventual conversion of the 48, Seattle’s trolley network will be at best treading water even as the county works hard to switch the network over to electric buses.

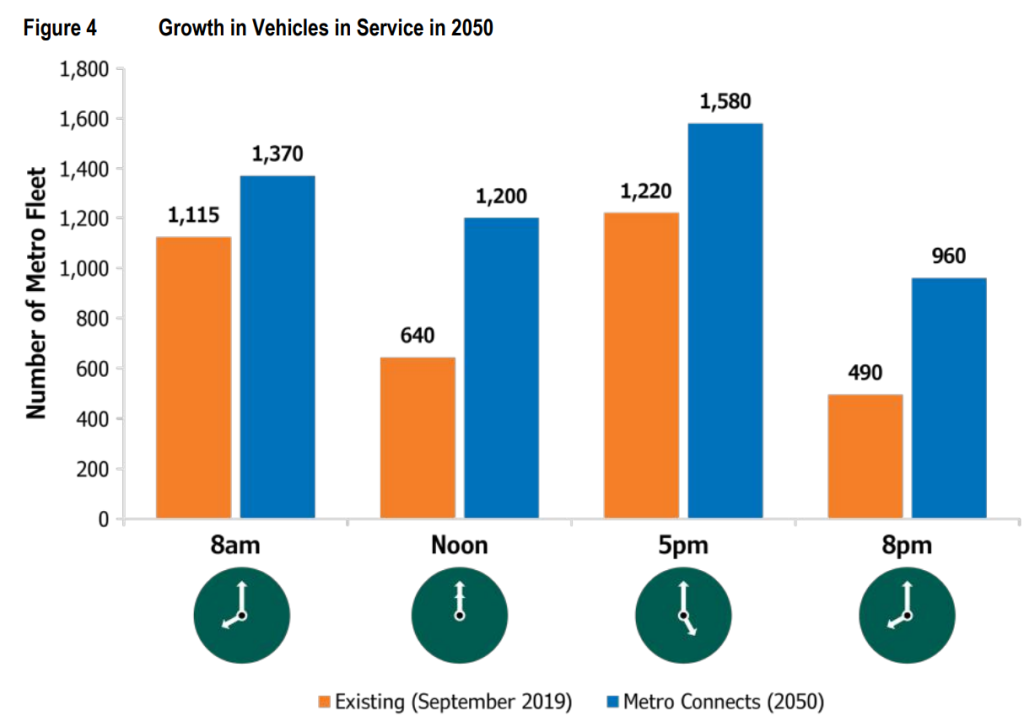

Metro’s 2027 plans for trolley network expansion include 20 new coaches, intended to support Route 48 but also potential increased service levels on other existing trolley routes. On paper, Metro’s service expansion plans would quickly outpace that, with the ambitious Metro Connects long-range plan calling for a significant increase in service and, by extension, the size of the fleet. If that vision is achieved, it would mean close to 30% more vehicles on the county’s roads at 5pm.

Metro Connects calls for Metro to “optimize and moderately expand” the trolley network by filling in gaps, expanding wire to some new streets, and increasing the use of trolleys on weekends. As it stands, Metro will regularly run diesel coaches on the trolley network on Saturdays and Sundays to deal with the impact of construction reroutes on some streets.

Without diversifying the fleet, Metro runs the risk of having its battery-electric bus transition impede service expansion. This summer, Austin’s CapMetro transit agency hit the brakes on its planned transition, halting the purchase of new battery-electric buses while it waits for the industry to catch up with its service needs.

Metro’s Jeff Switzer told The Urbanist that the agency still considered trolleybuses important, but raised several barriers that it faces in expanding the network, including infrastructure costs.

“Adding trolley wires is most effective on streets where there is a higher volume of bus traffic, and much less so on streets where fewer buses travel,” Switzer said.

Metro is considering trolley expansion on routes where battery-electric buses couldn’t reliably deliver service, and also routes where buses already operate underneath wire for substantial portions and could utilize in-motion charging for the portions without wires, Switzer said. He did not name any specific routes that are under consideration beyond the 48, but the Route 11 would presumably be at the top of the list, with approximately half of its new route under wire.

“The Trolley Bus program is a key component of Metro’s zero emissions strategy,” Switzer said. “Trolleys are a reliable zero-emissions technology and Metro will continue to invest in operating and expanding the program.”

Nonetheless, advancing an expansion of the trolley network would clearly take a strong partnership between Metro and the City of Seattle, and leadership on the County Council that is interested in seeing it happen. Until that happens, the system seems poised to carry on mostly as it exists today, stopping well short of its full potential.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.