The Olympics have become a leviathan for Paris, the Ile-de-France region, and the administration of Emmanuel Macron. It is both an attempt to redevelop suburbs of Paris into a new urban and social fabric via a dramatic investment of public and private capital into the Games. Though the Games have now commenced, the impact of its construction has already been clearly felt long before that.

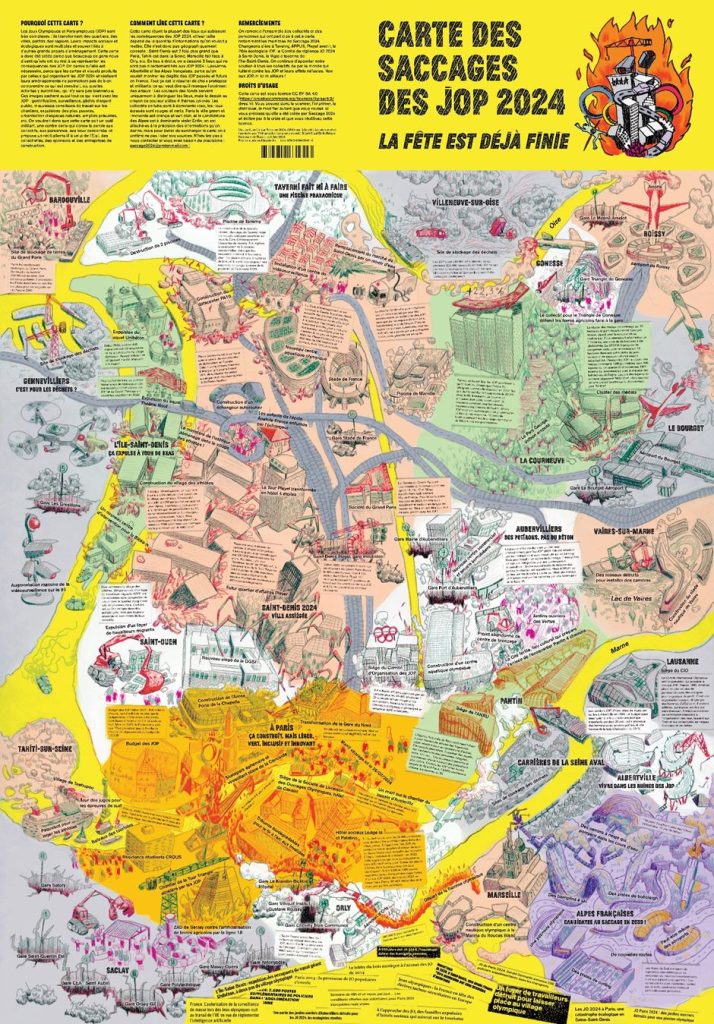

Some Parisians and French residents have greeted hosting duties with chagrin, and even consternation and anger. While Paris’s bid offers a promising example of French public planning, transit-oriented development (TOD), and public private partnership, it’s also faced strong criticism due to concerns about gentrification and greenwashing.

The Olympic Village is a case in point. Built as infill development on the urban fringe with a mix of public and social housing and the needs of Greater Paris in mind, the Olympic Village aims to be a symbol of French planning and building prowess. While there are many concerns about the Olympics, the Olympic Village may be a model for building social, sustainable, and transit-oriented development for American planners and citizens.

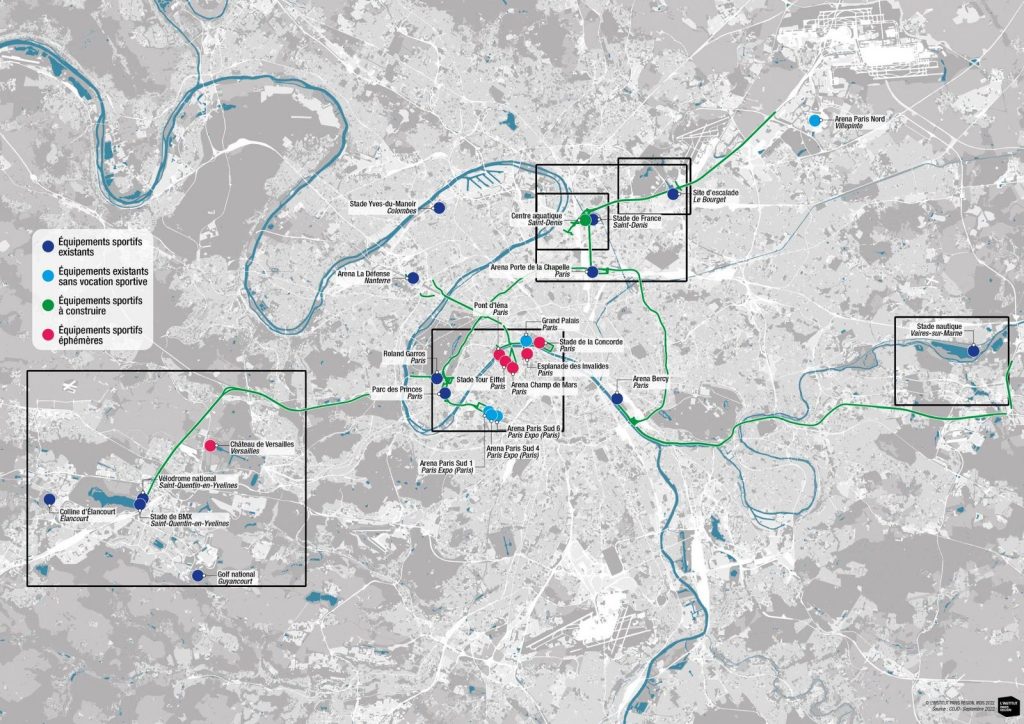

Paris, a city famous for its urban regeneration, is attempting to use the Olympics as a means to an end and overcome the de-industrialized rust belt around the city’s exterior. Much of the Games’ infrastructure and programs will be located outside of the city limits, in areas that have been traditionally neglected economically — the Seine-Saint-Denis and Plaine Commune, in particular. While the promises of the Olympic promoters to reinvest in the area and create a better quality of life are on the surface noble, they also present a challenge to avoid displacement of low-income residents, environmental damage, and social conflict.

The Olympics have long come under scrutiny for the pressure the Games have placed on cities to invest in temporary venues and amenities over the host city’s long term needs. As a result, the International Olympics Committee (IOC) has attempted to reform itself so that the Games will fit to the spatial needs of the Paris region.

“[T]he extant literature has established that hosting commonly results in a variety of injurious outcomes for cities,” Swiss geographer Sven Daniel Wolfe wrote in 2023. “These range from broken budgets and private profit at the expense of the public … to gentrifications, evictions, and white elephant infrastructures, occurring regardless of national or political economic cultures… This harm is often most visible in the host city spaces selected for intervention.”

In the face of this backlash, the IOC has attempted significant reforms to try and meet the needs of the host city. Much coverage and promotion of the Olympic Games by the IOC, Solideo (France’s public Olympics delivery authority), and the French and Paris governments stress the lack of white elephant projects, the focus on sustainability, and using the Games to meet the needs of the Paris region rather than the Games.

One of the most high-profile environmental efforts was the $1.5 billion cleanup of the long-polluted Seine River, which included improvements to Paris’s stormwater retention and sewer system. Aimed at allowing the Seine to host the swimming portion of the triathlon, the project could have benefits for the whole watershed that long outlast the Games — even as triathlon has been delayed after heavy rains temporarily spiked pollution in the river.

Yonah Freemark, a U.S.-based researcher with the Urban Institute, said that Paris has made some strides in using the Olympic Games to promote lasting urban renewal rather than a fleeting economic boost at great expense.

“Compared to previous Olympics, the Paris Olympics certainly has resulted in significantly less Olympics-focused infrastructure,” Freemark told The Urbanist. “There was no effort to build a new stadium, they were able to take advantage of the existing stadium, the new investments that have been made like this swimming centre are pretty minor. There just aren’t that many of them. You know, you see places like Sydney or Beijing that rebuilt entire sections that are city built gigantic new sports facilities that just was not the case in Paris.”

Olympic Village Eco-Quarter

One of the few permanent pieces of infrastructure is the Olympic Village. Built by Solideo with governance from the state, the Paris region and the city itself, the site features a variety of mixed-used development to meet the needs of Paris’s housing supply. A former brownfield on what was a largely industrial area, the village is an example of new urban development. The complex is vast and spans nearly 100 acres over three municipalities in Northern Paris. A giant sustainability-focused eco-quarter popular with French urban planners and architects, the village is bisected between the Seine and connected by a pedestrian bridge, which should also benefit future residents and help them get around without a motor vehicle.

Located near several metro stops, the village is the home for an estimated 15,000 athletes. A variety of housing designs are built into the new neighborhood to make the area feel organic and unique. In style, it is designed similarly to other French Eco Quartiers: relatively dense neighborhoods which use environmentally friendly building methods. Olympic Village buildings heavily used wood over concrete. Solar panels and gardens line the roofs, and after the Games these buildings will be converted into mixed-use housing and office space to create economic activity and social mix.

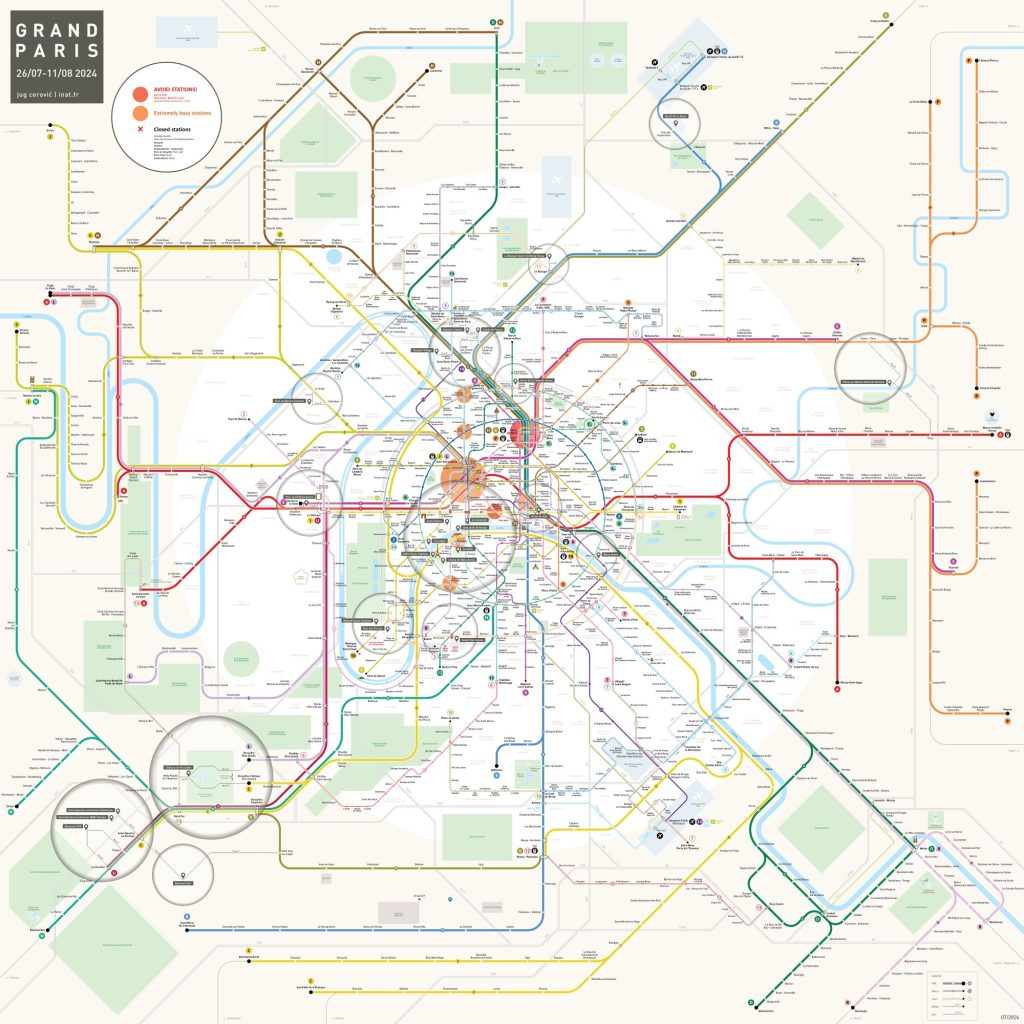

After the Games, the village will be home to 6,000 future residents located near Central Paris with ample access to rapid transit. The village will include: “6,000 residents, 6,000 office workers, two schools, two crèches [nursery/daycare], 1 new gym, plus a newly renovated gym, a large public space, improved access to the river and to Rue St Denis, a renovated high school, a grand ‘parc urbain’ or urban park, a fire department, a mixed use shopping and health facilities, and five lines of transport: [the RER] and lines 14, 15, 16, and 17 of the Grand Paris Express.” (translated by author)

Between 25% to 40% of the housing will also be turned into public housing to help handle Paris’s cost of living goals. The percentage is based on the various municipalities’ needs. France’s national government requires that cities hit ambitious affordable housing targets, and these goals have been heightened through cooperation with Paris and nearby municipalities. Although social housing is a subject of debate in contemporary politics, French urban planning laws require greater accountability for municipalities to meet social housing objectives than in the U.S.

In Greater Paris, much of this housing work is being done through multiple layers of governance, both from the top down and horizontally. The City of Paris has worked with its nearby municipalities closely for the past 20 years or more and with private funding from developers as well. This is a massive collaborative effort that incorporates strategic territorial planning to meet the needs of Paris and its citizens.

Compared to the U.S., the amount of work being put into public housing is remarkable. The village is a walkable, transit-rich large-scale infill development with much of the housing offered below the market rate. The scale of the project for social housing is something American cities have sometimes struggled to build. The Paris Olympic Village is a change from previous Olympic Villages in France, such as the Grenoble Olympic Village of 1968 – a garden city largely made out of cinder blocks, currently in a state of neglect in part due to its isolation from the rest of Grenoble. The new village is largely constructed out of wood when possible, and is meant to be a green, walkable eco-village.

The Olympic Village could be a case study for American cities on how to develop social housing connected to transit projects, as the village will be next to the Pleyel Junction, the new Aquatic Centre, and Stade de France, the national stadium built for the 1998 FIFA World Cup. Hopes are high that this area will become a major hub of economic activity like La Défense or Les Halles.

Criticism of Olympic development

Not everyone has bought into the hype, however. Concerns about the ecological impact of the games as well as gentrification have been protested by the anti-Olympic group Saccage (which in French means devastation). Largely led by local residents, the organisation has called the Olympics unaffordable and likely to lead to the expulsion of working class residents.

“The various devastations caused by the Olympic Games only accelerate the ecological problems and social injustices in our cities, and deprive us of the means to decide collectively about what surrounds us,” Saccage said (translated from French).

Critics have other concerns with the site, particularly its location for social housing right next to one of the most polluted highways in France. The high price of private housing for sale in the village has also drawn criticism.

Now that the Games have commenced, what was an industrial wasteland a decade ago is now a new neighborhood that will be home for thousands of permanent residents. We do not know how it will be looked upon by its residents and whether it will be remembered as a successful step in modern French urban planning in the long run. Will public housing, transit-oriented development, and ecological restoration, prove a successful and thriving model for the rest of the world to follow? Or will it end up with a mixed reputation like that of previous post war banlieues and other new towns master-planned from scratch and imposed on communities? It will take time, and no doubt the lived experiences of the residents to find out if it will be successful in the end.

The Olympic Village is a case study of transit-oriented development and public housing. The approach to make a mixed use neighborhood that has public housing and transit are things worth implementing for American cities looking to rezone, infill, and promote large public housing projects. It also shows an Olympics based on avoiding wasteful ‘white elephant’ spending, and it’s a model that we should expect to see followed in Los Angeles in 2028.

To quote Yonah Freemark, “I think that [the focus on avoiding less useful projects] is a reflection of the new approach to Olympics Games [that] the International Olympics Committee has tried to encourage. So from that perspective, I think it’s a good thing.”

Sam Levitt

Based in France, Sam Levitt is an American writer who holds a Masters in History from University College Dublin. His love for hiking, urban planning and history has influenced his decision to live abroad and write along the way. Nestled in the French Alps with his wife and cat, Sam plans to expand his knowledge of Urban Planning by attending a local university in Fall 2023. His experiences living in the Czech Republic, Ireland and France have greatly impacted his perspective on urban planning. He enjoys a good pint of Guinness, talking about history with friends, and gardening.