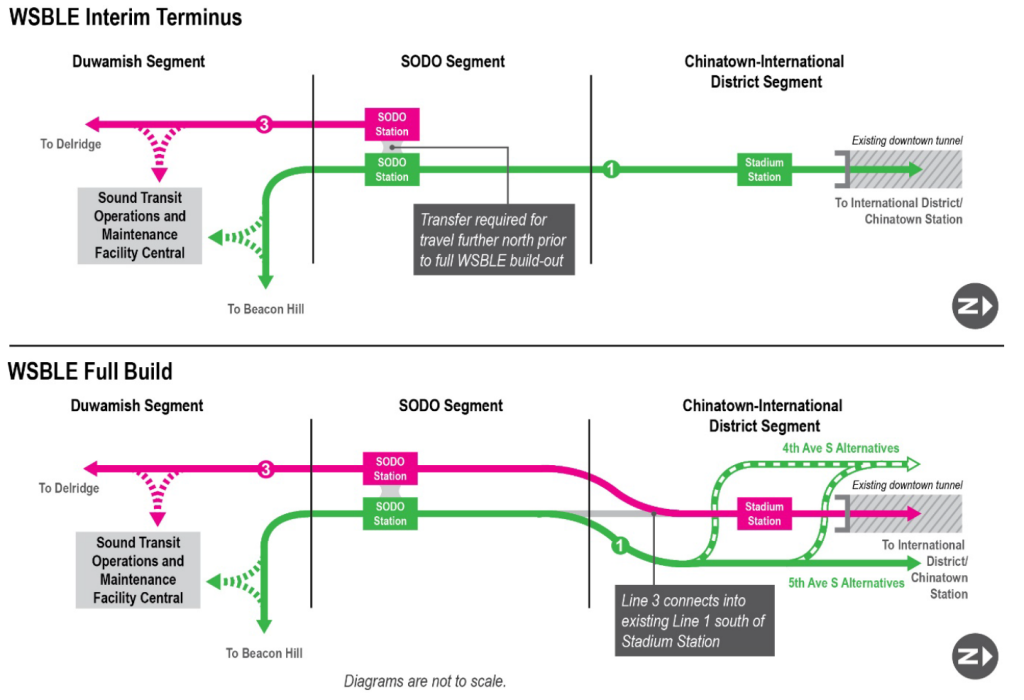

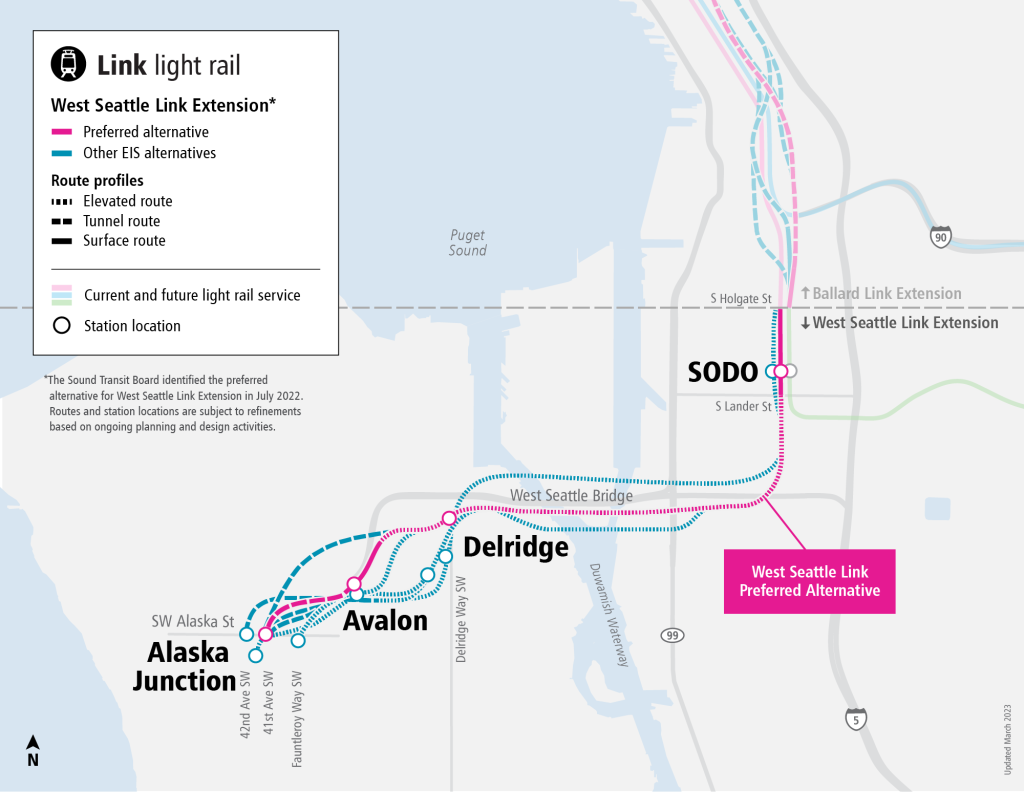

When construction finally starts for Sound Transit 3 (ST3) light rail projects within the City of Seattle, fewer neighborhoods will be impacted as significantly as SoDo. At the nexus between the West Seattle Link and the Ballard Link Extension projects, SoDo will see some of the longest construction timelines of any ST3 projects. The agency hopes to start construction on both projects in 2027 and open the West Seattle line by 2032 and a partial segment of the Ballard line by 2037 — with the full line to Ballard tabbed for 2039. On top of the direct impacts from construction, which will last nearly a decade, another major change is headed SoDo’s way: the permanent closure of the SoDo busway.

A quiet workhorse of Seattle’s transit system, the SoDo busway, which opened in 1991, whisks riders along a dedicated lane in each direction from Spokane Street in the south to Royal Brougham near the stadiums, keeping buses moving parallel to the existing 1 Line tracks and allowing easy transfers. That busway today carries over 800 bus trips every weekday, but is set to be replaced with a second set of tracks to carry Link riders between West Seattle and Downtown — no matter what alternative the Sound Transit board chooses for a light rail alignment.

Those bus trips will need to go somewhere, so Sound Transit and the City of Seattle have been coordinating on proposed changes to nearby 4th Avenue S as the obvious choice for a new priority bus corridor in SoDo.

Where today 4th Avenue S tops out at 12 buses per hour during a busy evening hour, that will increase to nearly 60 buses per hour with the closure of the busway. As part of its environmental review for West Seattle and Ballard Link, Sound Transit will have to quantify the impacts that come from shifting those buses and find ways to mitigate those impacts. That mitigation will center Level of Service (LoS) for cars and trucks, the amount of time drivers will wait in added traffic.

However, 4th Avenue S is also one of the most dangerous streets in Seattle for all users, but particularly people outside of cars. Between 2017 and 2023, there have been eight fatal crashes and 17 crashes resulting in serious injuries along 4th Avenue, with close to half of those people walking. The high number of wide lanes, which are designed for freight traffic, along 4th is a big contributor to speeding, which average close to 10 mph over the 30 mph speed limit.

People walking and biking through the area have long been an afterthought, with anyone not biking on the short stretch of the SoDo Trail in the neighborhood likely using the narrow sidewalks.

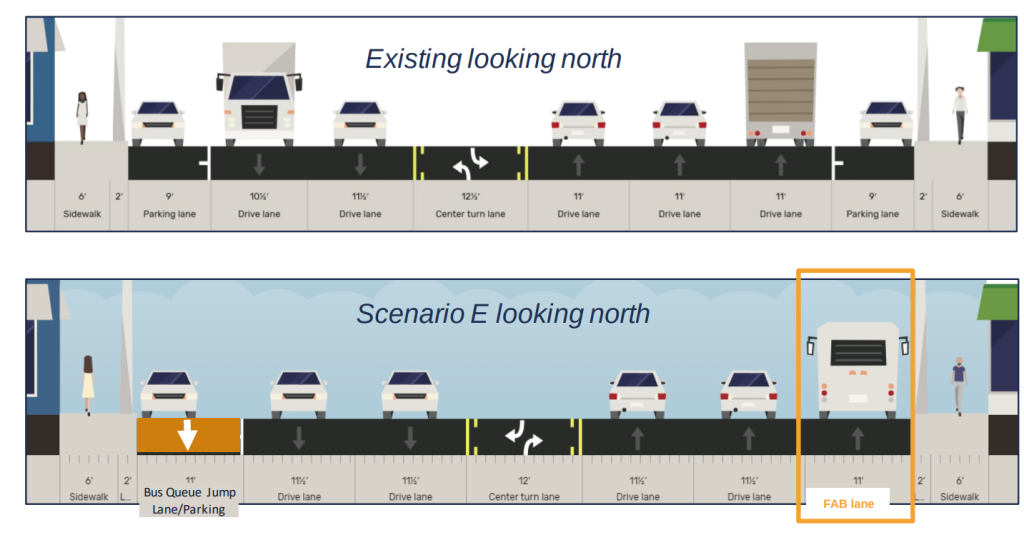

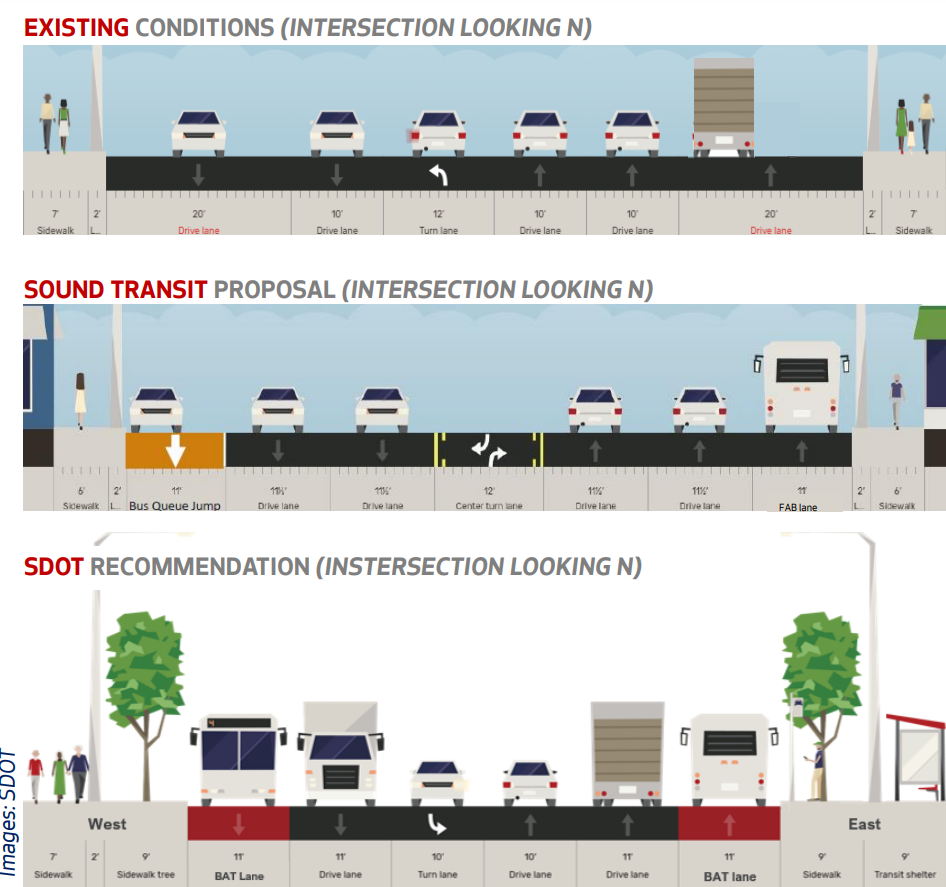

Nonetheless, the initial proposal from Sound Transit, produced in coordination with the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) and other partners like the Port of Seattle, would largely leave 4th Avenue S as it exists today. Apart from a short freight-and-bus (FAB) lane for northbound traffic only starting just south of S Lander Street and ending at S Holgate Street, buses would share space with general purpose traffic. Bus queue jumps at intersections would give buses a head start at Holgate and Lander when heading southbound.

At the bus stops around Lander and Holgate Streets, the Sound Transit proposal would widen the narrow 4th Avenue sidewalks by only two-and-a-half feet, while leaving most 4th Avenue sidewalks unchanged. Meanwhile, the agency projects the number of transit riders using the stop at S Lander Street will increase tenfold when Ballard Link opens.

Sound Transit’s mitigation plan would do little to improve safety on 4th Avenue. Already dire, the additional pedestrian traffic on the street, may actually cause the situation to degrade further. According to a presentation produced by SDOT earlier this year and obtained by The Urbanist via a public records request, the department is not onboard with the plan, saying that the designs do “not meet SDOT standards. […] Sound Transit’s proposal prioritizes mobility for freight, transit, and general purpose, but worsens conditions for safety.”

Sound Transit’s proposal also leaves out improvements to other stops along 4th Avenue that aren’t at the major intersections. Perhaps most worryingly, the proposal would actually widen some of the lanes on 4th Avenue. “Channelization will increase speeds, worsening pedestrian safety and crashes,” the presentation notes.

SDOT envisions the future of 4th Avenue quite differently, proposing to widen sidewalks, plant street trees, add an additional pedestrian crossing at S Walker Street, and create a curbside business access and transit (BAT) lane all the way from Royal Brougham to Spokane Street. In contrast with Sound Transit’s proposal, freight wouldn’t be allowed to use this bus lane due to the expected peak hour volumes, though that could potentially change in the future. The proposal for street trees is intended to combat SoDo’s status as one of the city’s most intense urban heat islands.

SDOT proposes to implement the changes in two phases, adding sidewalk extensions around all bus stops in the corridor and at the major intersections by the time bus riders switch over to 4th. South of S Massachusetts Street, a full rechannelization would come later and not be directly tied to the Sound Transit mitigation efforts.

Funding for the proposal is another matter. Sound Transit’s north star will be the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) process, which will look narrowly at vehicle delay. The agency recently adopted a new policy around betterments, or ancillary improvements that come with transit lines, intended to curb the practice of cities putting nice-to-have elements on the Sound Transit tab. But Sound Transit does need to pay for the direct impacts from the West Seattle and Ballard Lines, which are much more broad and multifaceted than a simple increase in bus traffic.

“While the relocation of buses to 4th Avenue is a change proposed by the Sound Transit project, SDOT may decide to make additional improvements to 4th Avenue South that are separate from Sound Transit’s work,” SDOT spokesperson Mariam Ali told The Urbanist. “However, there is currently no timeline or secured funding for a potential future project. SDOT would conduct public engagement for any future project elements.”

A substantive overhaul of 4th Avenue will likely see pushback from freight and business advocacy groups intent on keeping the street as free-flowing as possible, and from nearby property owners concerned about changes to access and losing parking. Minor changes to 4th Avenue intended to improve safety following clearly preventable deaths have been put on ice before thanks to such opposition, and these changes go much further than that. If the goal is to increase road safety rather than worsen the situation, implementing the initial Sound Transit proposal would clearly be a mistake.

After months of negotiations behind closed doors, SDOT expects to start community engagement around the issue near the end of 2024 and into 2025. Two frequent opponents of safe streets projects in SoDo — the Seattle Freight Advisory Board and the SoDo Business Improvement Area (BIA) — factor heavily in those plans.

“SDOT has had some early discussions with the Port of Seattle and the Northwest Seaport Alliance to understand and address their concerns,” Ali said. “When public engagement starts later this year and into 2025, Sound Transit and SDOT will engage more broadly with the SODO BIA and its members, as well as with the City’s transportation modal boards, which include the Seattle Freight Advisory Board, to continue to hear directly from users of the 4th Avenue South corridor.”

The episode serves as a clear reminder that for so long, “mitigating” transportation projects has meant alleviating their impact on drivers and traffic, and not taking a broader look at what is best aligned with city and regional goals around safety, environmental justice, quality of life, and climate. But here is a clear opportunity to do better and chart a new path.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.