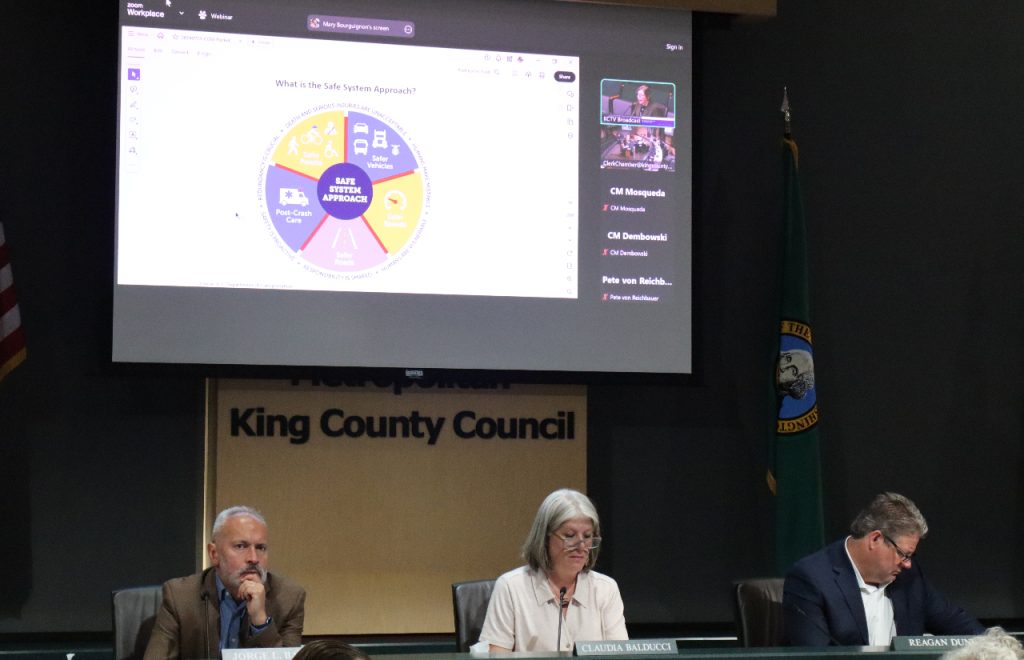

Faced with a troubling rise in devastating traffic crashes both regionally and nationally, King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci is pushing for county government to step up its role in reducing traffic violence. On Tuesday, a county council committee officially voted to endorse a “Safe Systems” approach to achieve a goal of zero serious injury and fatal crashes. The motion also asked County Executive Dow Constantine to develop a plan that includes all county departments, not just the ones that would normally be working on crash reduction.

The Safe Systems approach, which has reached a national level of prominence under the Biden Administration, is essentially a more direct embrace of the successful Vision Zero model adopted in Sweden in the late 1990s. It eschews outdated road safety approaches that have relied primarily on public education and spot enforcement to improve outcomes, instead looking at the ways that transportation facilities can be designed to be more accepting of mistakes, reducing the overall severity of crashes and protecting people who are not in cars.

“In my view, [a] Safe System is really about making sure that we are building and creating roadways and pathways that are as forgiving as possible,” Balducci told The Urbanist this week. “What I say to people, when they really put it to me is: we are creating a system that encourages people to go the speed that is safest in the place where they are.”

According to preliminary data from the Washington State Department of Transportation, 1,092 people were either killed or seriously injured on roadways in King County in 2023, a 15% increase compared to 2022. This motion asks the County Executive to develop a report by next January that includes a “coordinated, multiagency safety plan” to get to the goal of eliminating traffic fatalities and serious injuries, and asks for a reasonable timeline that the County can attach to that goal.

“I was surprised to learn that we didn’t have a Vision Zero policy at King County, and I think it’s very important that we do have one, or at least a Safe System policy,” Balducci said. “But what’s different to me is, when you think about the breadth of authority and programmatic areas that the county covers, we have kind of a unique ability to engage in this work.”

Balducci noted that the King County Roads department is engaged in safety work, but the County also has the resources available at Harborview Hospital — the only Level 1 trauma center for a region encompassing four states — along with King County Metro, King County Parks and Public Health – Seattle & King County.

“The legislation asks a question: it says, let’s bring all of this expertise and responsibility together and see what we can do together to really advance the cause,” Balducci said.

Many cities around the county have Vision Zero programs in place; in 2015 the two largest cities of Seattle and Bellevue both signed onto the idea of eliminating fatalities and serious injuries in traffic by 2030. And while those cities have seen success in improving outcomes when it comes to specific programs, it has not led to a broad overhaul to the design of their transportation systems or a significant bending of the trend line toward zero traffic deaths.

In 2022, when the incoming director of the Seattle Department of Transportation, Greg Spotts, pledged a “top to bottom” review of the city’s Vision Zero program in the face of increasing fatalities and serious injuries, he acknowledged that the program had continued to exist in a “little pocket of the organization.”

“This is much more than a slogan or a tagline,” Leah Shahum, executive director of the Vision Zero Network told the committee this week. “It’s much more than even a program, or a resolution. Of course, it’s got to start there, but Vision Zero and the Safe Systems approach are fundamentally different, they are a paradigm shift.”

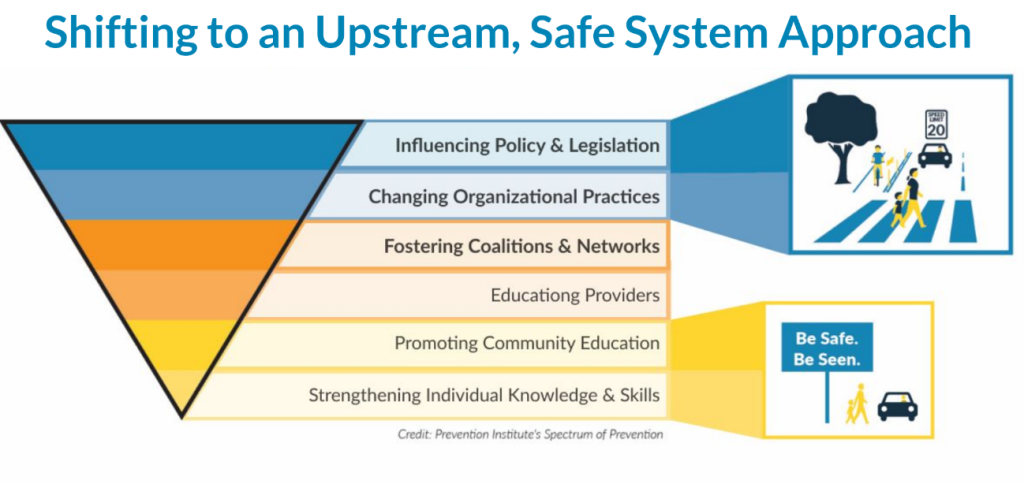

“With a Safe System approach, we really want to look more upstream,” Shahum said, noting an intentional shift toward policymaking and away from focusing on individual behaviors and intersections. “What we can do with a Safe Systems approach is, frankly, bring in more players and stakeholders. […] It’s not just a transportation problem or a transportation silo you’re working in; it is bringing in public policy folks. It is bringing in public health. It is bringing in your transit providers and school districts and others to really be working on this together, and to really be taking a different approach.”

In the end, the motion passed out of committee by a unanimous 8-0 vote, with Councilmember Peter von Reichbauer not present. But the policy trade-offs that come with taking a Safe Systems approach seriously are still down the road.

King County continues to explore intelligent speed assistance

While that conversation was conducted mostly in the abstract, at the same meeting the County Council also got an update on an initiative that would truly advance a Safe Systems approach at county government and potentially prompt other jurisdictions to follow: installing speed-limiting technology on official vehicles.

A provision added to the current county budget asked for a feasibility report looking at the potential of adding intelligent speed assistance (ISA) to the non-revenue fleet, which would exclude King County Metro coaches and vans. That report, which The Urbanist covered last fall when it was delivered, concluded that virtually the entire non-revenue fleet could be equipped with technology that required an override to exceed a posted speed limit, with a modest cost of a few million to do so.

But the report also seemed to paint the goal of a safer fleet as being in conflict with the county’s other high-profile goal of getting to an all-electric car fleet by 2030 and all-electric bus fleet by 2035. “It is essential for the Fleet Services Division to maintain focus on the transition to EVs,” the report noted. “It is important to recognize that the integration of ISA technology could introduce complexities and potential impacts on the achievement of EV goals.”

That seemed to be fully debunked Tuesday, with experts from the Volpe National Transportation Systems Center describing the initial results from a pilot program in New York City, in which 300 vehicles were installed with intelligent speed assistance, with a result of 99% of fleet miles travelled occurring within the set speed parameters, and other positive outcomes like a reduction in hard braking events.

“The New York City initiative is happening concurrently with electrification,” The Volpe Center’s Alex Epstein said. “They currently have about 4,000 vehicles that have been electrified… about half of the vehicles in the ISA fleet are electric, and about half are not, and we’re not aware of any issues that they’ve encountered during that implementation or in terms of operating or installing the ISA aftermarket systems. They are certainly pursuing those in parallel and see those as a complimentary initiatives.”

Whether the County moves forward with implementing ISA will be just one illustration of whether county government is ready to do what it takes to implement the paradigm shift that would take Vision Zero and Safe Systems from being more than slogans in King County.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.