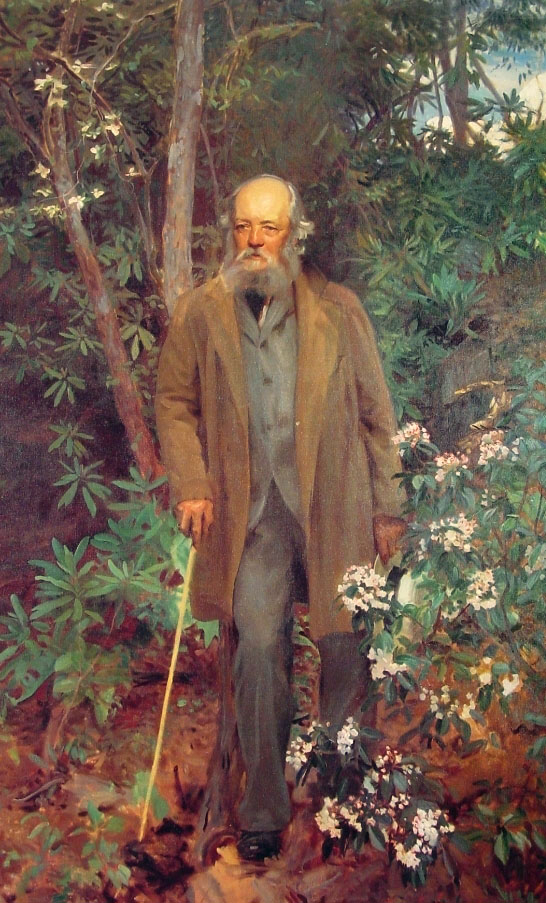

Frederick Olmsted, the father of landscape architecture, had city-as-park designs for Tacoma, but was rebuffed.

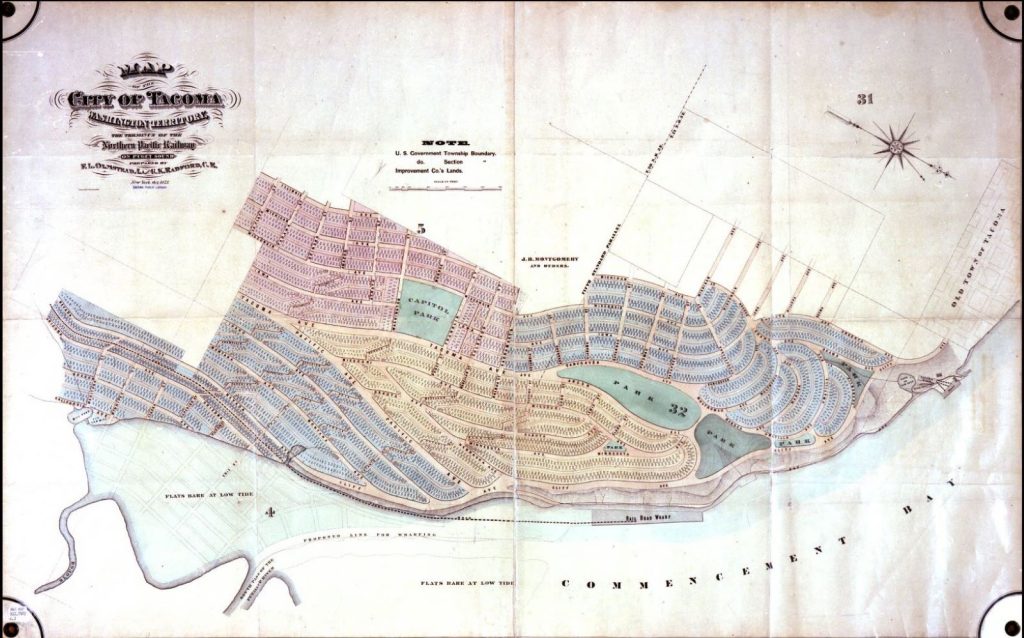

Despite an unique geography shaped by water, the layout of Tacoma speaks to a dominant mode of planning cities in the late 1800s: draw a broad rectangle and subdivide it into squares. This basic plan was recommended for Tacoma by James Tilton, head surveyor of the Washington Territory.

Of this plan, the Weekly Pacific Tribune on October 3, 1873, wrote: there are to be “three main avenues 100 feet in width” running parallel to the waterfront. “Two others slanted diagonally up the hill…” These thoroughfares enclosed “blocks 120 feet deep which ended in 40-foot-wide streets.”

To a large extent, this plan for Tacoma is what we have today. It could have been drastically different. For 43 days, Tacomans considered laying out their fledgling city according to a plan “unlike that of any other city world,” according to Thomas Prosch, publisher of the Pacific Tribune. This unique proposal was that of Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr.

The matter of Tacoma’s plan was, like so much in Tacoma’s early days, directly related to the railroad. The Northern Pacific Railroad company and its heads were looking to spur the growth of a major city on the land it owned at the western terminus of the intercontinental railroad that it had just went heavily into debt building. Among other schemes, railroad executives saw an opportunity in the hiring of one of the nation’s rising designers — Olmsted had made a reputation through park designs in major cities on the East Coast and as a capable project manager in both public and private enterprises. His profile could jumpstart the real estate and property development dreams of Tacoma’s early leaders.

Even after accepting the commission, Olmsted never actually came to Tacoma. He would know Tacoma only through the reports and sketches sent to him by G.K. Radford, an engineer whose expertise would help address some of the drainage and elevation challenges, something Tilton had failed to adequately resolve through his plan.

Olmsted delivered a radical plan for Tacoma, even by today’s standards. In contrast to planning paradigms of the time, his plan rejected the grid. His plan was soft; a rounded townsite composed of serene, park-like spaces contained by a network of curving, tree-lined thoroughfares.

No straight lines, no right angles. All lots were allotted a frontage of 25 feet, presumably to encourage landscaping in front of each home that would contribute to the city’s overall park-like feel. His curving streets meant that there would be few corner lots and limited street crossings, which to Olmsted meant fewer collisions and (in the absence of paved roads) less accumulation of mud and dust.

The plan called for three grand avenues, Pacific, Tacoma, and Cliff. Pacific would connect the railroad to the countryside; Tacoma would intersect Pacific and connect the old and new town, and lead to the beach; Cliff would run along the bluff for a distance of two miles.

Each of these grand avenues would lead residents and visitors alike to specific places and activities. Pacific would lead to commercial and industrial centers; Tacoma Avenue would lead to the city’s major parks (of which there would be seven), and Cliff to the “magnificent” residences and their grand water views.

One of the most striking features of Olmsted’s plan for Tacoma were its seven parks. Olmsted had come to fame and success as a proponent of parks in cities, not only because they provide urban residents respite from the city, but because parks were sites of civic training. His designs for parks, park boulevards (or parkways, as he called them), and park systems emphasized this socialization function.

And one could read Olmsted’s plan for Tacoma using a similar lens.

Of the total 1,000 acres comprising the plan, 100 of them were set aside for parks. Olmsted argued parks (and his designs for them) played a central role in democracy and forging a healthy society. To create a democratic society, he wrote in 1853, it would be necessary to have more “parks, gardens, music, dancing schools, reunions” because these provide for “unconscious, indirect recreation.”

In 1858, in support of his vision for a central park in New York, Olmsted said that the park would be judged to be “a democratic development of the highest significance and on the success of which, in my opinion much of the progress of art and aesthetic culture in this country is dependent.”

In 1863 and also of Central Park, Olmsted wrote: “This area is situated in the centre of the city, having a population not altogether homogenous, reared in different climes, and bringing to the society of the metropolis views of labor and ideas of social enjoyment differing as widely as the temperature of the various countries of their origin […] The work of fusing the people of differing nationalities into a homogenous body can be accomplished only during the life of two or three generations, and it would be difficult to prescribe rules that would satisfy these dissimilar tastes and habits. The most that can be attained at the Park, is to afford an opportunity for those recreations or entertainments that are generally acceptable.”

Olmsted said and wrote much about the democratizing function of parks, and how parks, through their design, could help deliver a certain type of society. He was certain that his parks should offer a reprieve from the closed-in and often polluted spaces of the Gilded Age city; he was more certain that parks should provide people from lower classes, the poor, and immigrants an opportunity to learn how to be a different — in his eyes more “civilized” — urban resident.

In Olmsted’s view a park was for everyone; he also saw the park as an ideal site to lead everyone to behaviors that were “generally acceptable.” Today, Olmsted would not be considered as progressive in his ideas.

Olmsted notoriously fought Irish-American politicians who sought to use parks for fundraising and for entertaining political supporters. He was opposed to zoos, carousels, athletic fields, and bandstands — despite their popularity, especially among the masses.

The park was as much for leisure as it was for education. Through design, Olmsted sought to integrate “coarse” immigrants into an idealized social fabric of the American genteel. In many cases, his site selection directly displaced communities of color. Seneca Village, an established community of property-owning African Americans was famously destroyed in the siting of Central Park.

Certainly, lots of displacement had already happened in Tacoma by the time Olmsted created his plans for the city. Whether or not his plan would contribute to more of this displacement is a question for another writing. What cannot be denied is that beyond Olmsted’s technical ability, the famed landscape architect and his ideas about cities and its residents spoke to the propertied, middle-class White men who had their own designs for an emerging Tacoma.

Even though Olsmted proffered a plan for Tacoma that aligned with the aspiration of railroad executives and land speculators, Olmsted’s plan for Tacoma was not immediately popular. Not only did the plan deviate from what people were accustomed to when it came to the physical layout of a city, it also suggested that a city could be tranquil and serene.

If Olmsted came to fame by offering people an escape from the city within the city through his parks, the plan for Tacoma made a park out of the whole city. And this idea of a city was totally incongruent with the sense that a city is a place for business — for making money.

The plan was maligned by regional critics. The Portland Bulletin poked gentle fun at Tacoma in saying, “Tacoma is already a city set upon a hill, or two hills for that matter, it would be ridiculous for it to copy after unpretending places like Chicago or San Francisco. Tacoma resolves to have an individuality and to assert it…”

Ultimately, the plan would not be adopted. It came down to the plan being bad for business. Would-be business owners who had seen others profit from corner shops and stores at a busy intersection, describing the lack of grid as “a basket of melons, peas, and sweet potatoes,” adding that the street patterns reminded them of “everything that has ever been exhibited at agricultural shows, from calabashes to iceboxes.”

Thus, 43 days after Olmsted presented his plan, the landscape architect was presented with a letter of dismissal. Perhaps Tacoma desired only the prestige and national acclaim that came with getting an Olmsted plan drawn up rather than the headache and financial sacrifice it would have taken to follow it.

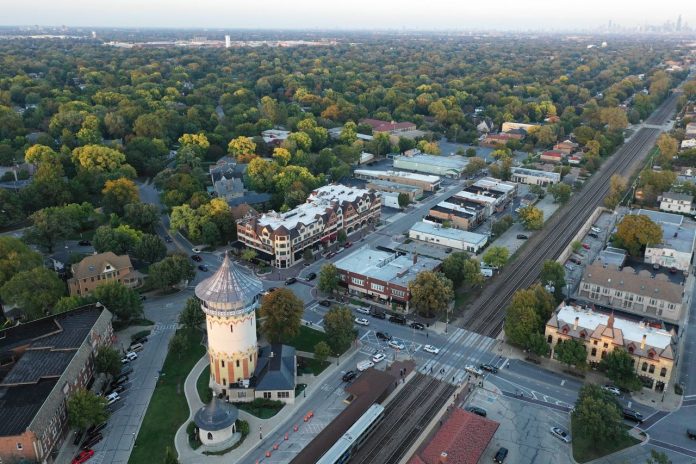

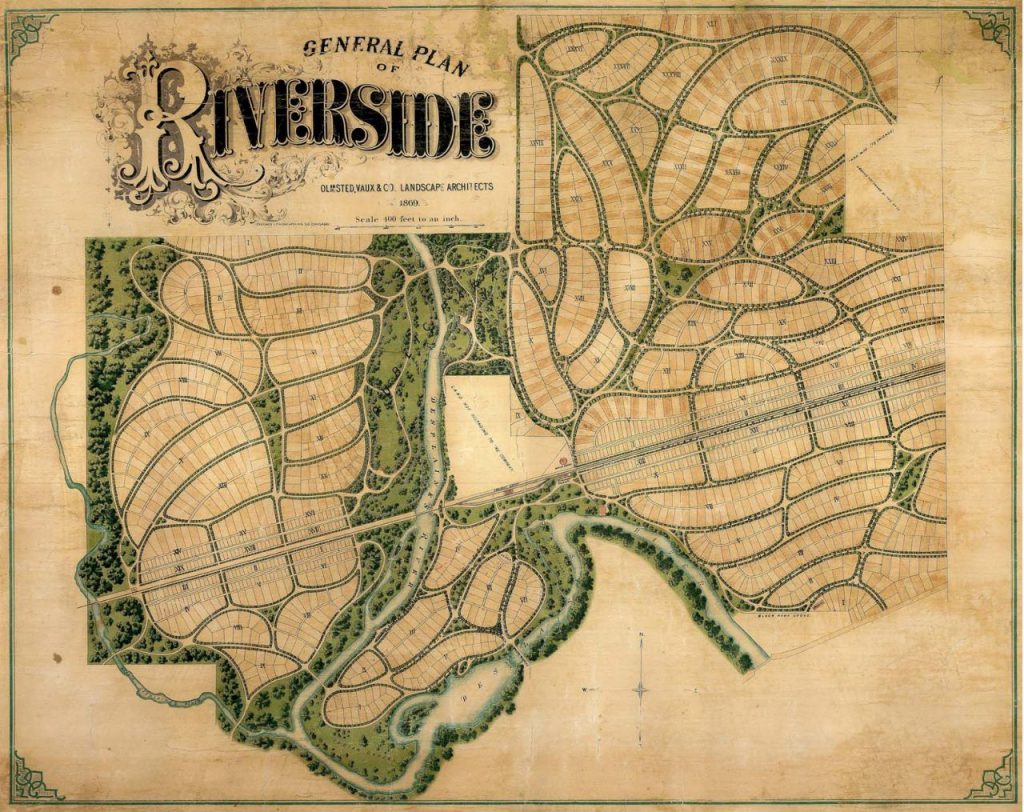

If one wanted to see something like what Tacoma could have been had it been developed according to Olmsted’s plan, one can travel to Riverside, Illinois. A planned suburb of Chicago, Riverside was designed by Olmsted and his often-partner, Calver Vaux.

Like Tacoma, the site that was to become Riverside, was created through the formation of a community that sprang up in relation to the railroad. Emery E. Childs arrived there in 1868 and after forming the Riverside Improvement Company, purchased a 1,600-acre tract along the Des Plaines River and Chicago, Burlington and Quincy Railroad line.

Like the heads of the Tacoma Land Company, Childs and his partners commissioned Olmsted to design the new community. Olmsted and Vaux completed the plan in 1869. It called for curvilinear streets that followed the Des Plaines River. Olmstead wrote that Riverside’s plan would demonstrate “gracefully-curved lines, generous spaces and the absence of sharp corners, the idea being to suggest and imply leisure, contemplativeness and happy tranquility.”

In Riverside, the central train station was also designated as a key site in the plan; also like Tacoma’s plan, a grand park system served as a focal point.

In key ways Tacoma did not become anything like what Olmsted envisioned. In other ways, it has become a lot like what Olmsted desired for it.

Pacific Avenue runs along the water and further south, eventually leading to the country, as Olmsted imagined. There is no Cliff Avenue that directs us towards stately views and wide water vistas; we have I-705 and Schuster Parkway instead. Tacoma Avenue we do have, and it does lead us to one of Tacoma’s best parks, Wright Park.

Rather than lush tree-lined boulevards and a system of prominent parks, Tacoma’s current landscape looks a lot more like a typical U.S. city. Wright Park is roughly where Olmsted laid out a major park, as is Garfield Park and the surrounding greenbelt ravine. Instead of 10% of Tacoma’s land designated as park or greenspace, it’s only 7%. A grand “Capitol Park” in the heart of downtown never came to pass.

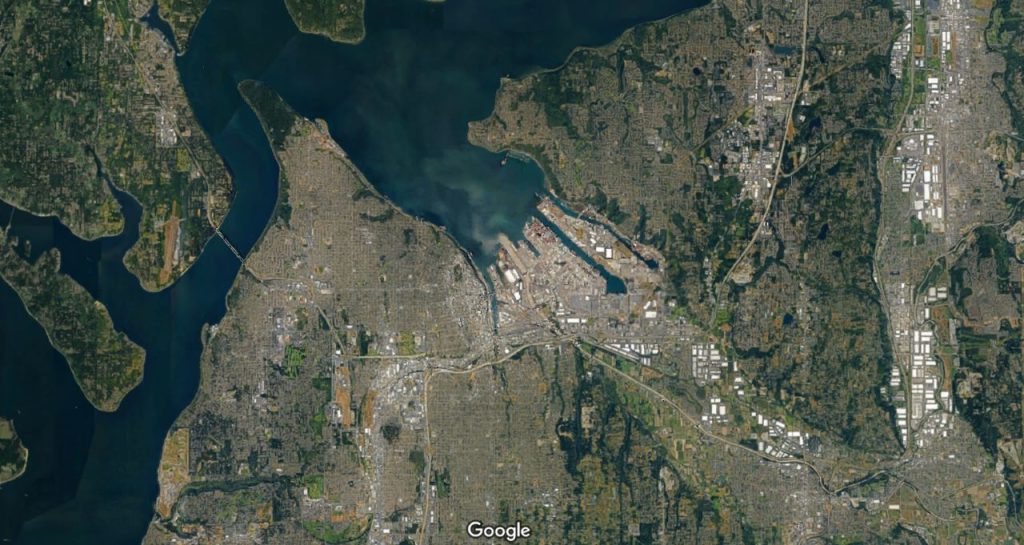

And it’s not just parks: whereas Olmsted imagined a forested park city, 21st century Tacoma has the least tree canopy coverage of any Puget Sound city, according to a Washington State Department of Natural Resources assessment. Tacoma’s 20% tree cover is half that of Bellevue, and well behind Seattle as well.

Olmsted may not have made as much of a physical impression on Tacoma as he did in other cities in the U.S., but his idea of urban parks and public places — and the way they work on us — continue to define the public experience across the land. Olmsted’s idea of parks within cities was informed by the assumption that cities were inferior to “the country,” and that parks exist in cities to allow city dwellers relief from the city.

More troubling is Olmsted’s sense that parks in cities were ideal sites of assimilation and social engineering.

Olmsted’s plan for Tacoma did not come to pass, but his ideas about parks and the people who use them remain with us today in the space and places he created across our region and the U.S.

Rubén Casas

Rubén joined The Urbanist's board in 2022. He is a scholar and teacher of rhetoric and writing at the University of Washington Tacoma. He is also the faculty lead of the Urban Environmental Justice Initiative at Urban@UW. In his work and advocacy, Rubén examines how cities and the institutions that comprise them imagine, plan, and build in ways that promote and/or discourage community and a sense of place.