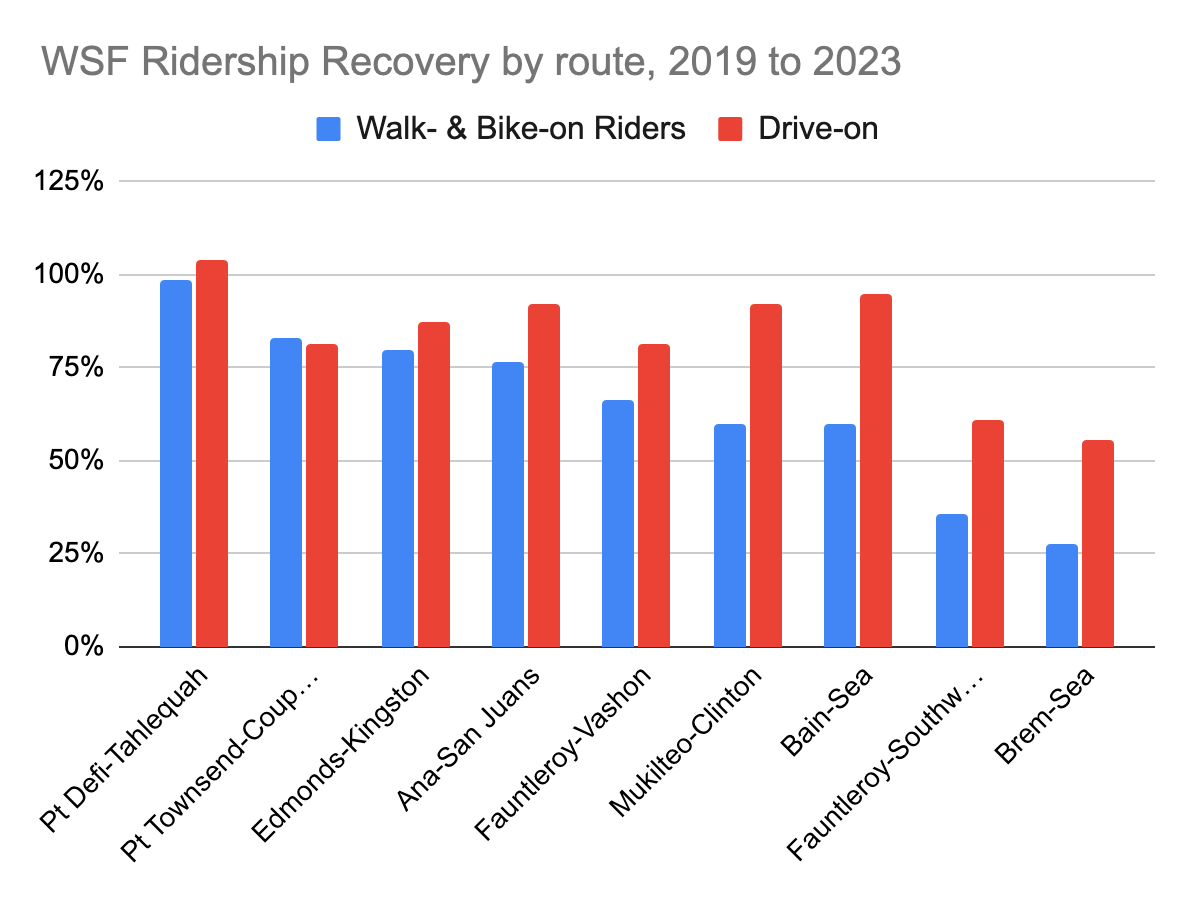

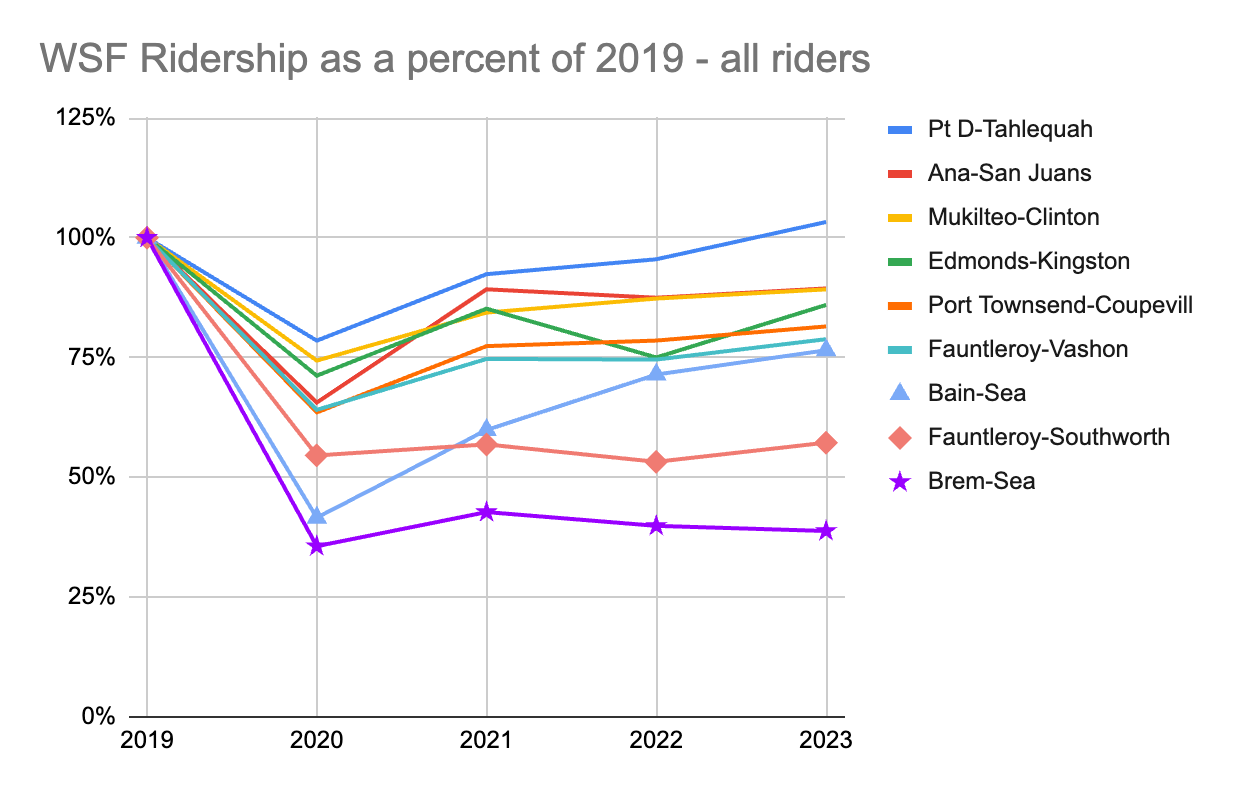

Washington State Ferries (WSF) ridership has recovered from the pandemic faster than nearly any public transit agency in the state. 2023 WSF ridership recovered to 78% of the 2019 ridership, better recovery than all but three Washington state transit agencies. But the recovery has been uneven, with drive-on ridership (drivers, passengers, and motorcycles) recovering much faster than ‘walk-ons’ (pedestrians and bicyclists).

Drive-on ridership has recovered well, from 16.8 million riders in 2019 to 14.6 million in 2023, a 87% recovery rate. But the number of people walking or riding onto the big boats fell from 6.9 million to 3.9 million since the pandemic, a recovery rate of just 56%. In 2023, WSF served 3 million fewer walk- and bike-on riders than in 2019. Where did all the riders go?

In an effort to understand where walk-ons have gone, I evaluated four hypotheses. Using publicly available data from Washington State Ferries, Kitsap Transit and King County Metro, I compared full year ridership from 2023 against 2019 ridership, the last year before the pandemic.

- Fast Ferries from Kitsap Transit and Metro are outcompeting WSF for riders.

- Work-from-home reduces the number of commuter trips.

- Reduced and unreliable ferry service lowers ridership.

- Travelers choose to ‘drive around’ through Tacoma.

I found support for each of these four factors, suggesting it’s the confluence of these headwinds that is creating such a drag on walk-on ridership at WSF. Read to the end for some possible solutions to right the ship.

Why walk-ons matter

Walk-on ferry passengers provide a plethora of benefits and fewer drawbacks than drive-on passengers. Because WSF boats have virtually unlimited space for walk-on passengers, unlike for cars, the boats never sell out. Walk-ons don’t cause traffic problems when the boats disgorge hundreds of cars, as on Seattle’s waterfront, Kingston, Port Townsend and Bainbridge. Walk-ons support local transit agencies by transferring to buses and trains. And walk-ons are more likely to support businesses near the ferry terminals.

What happened to all the ferry walk-on passengers?

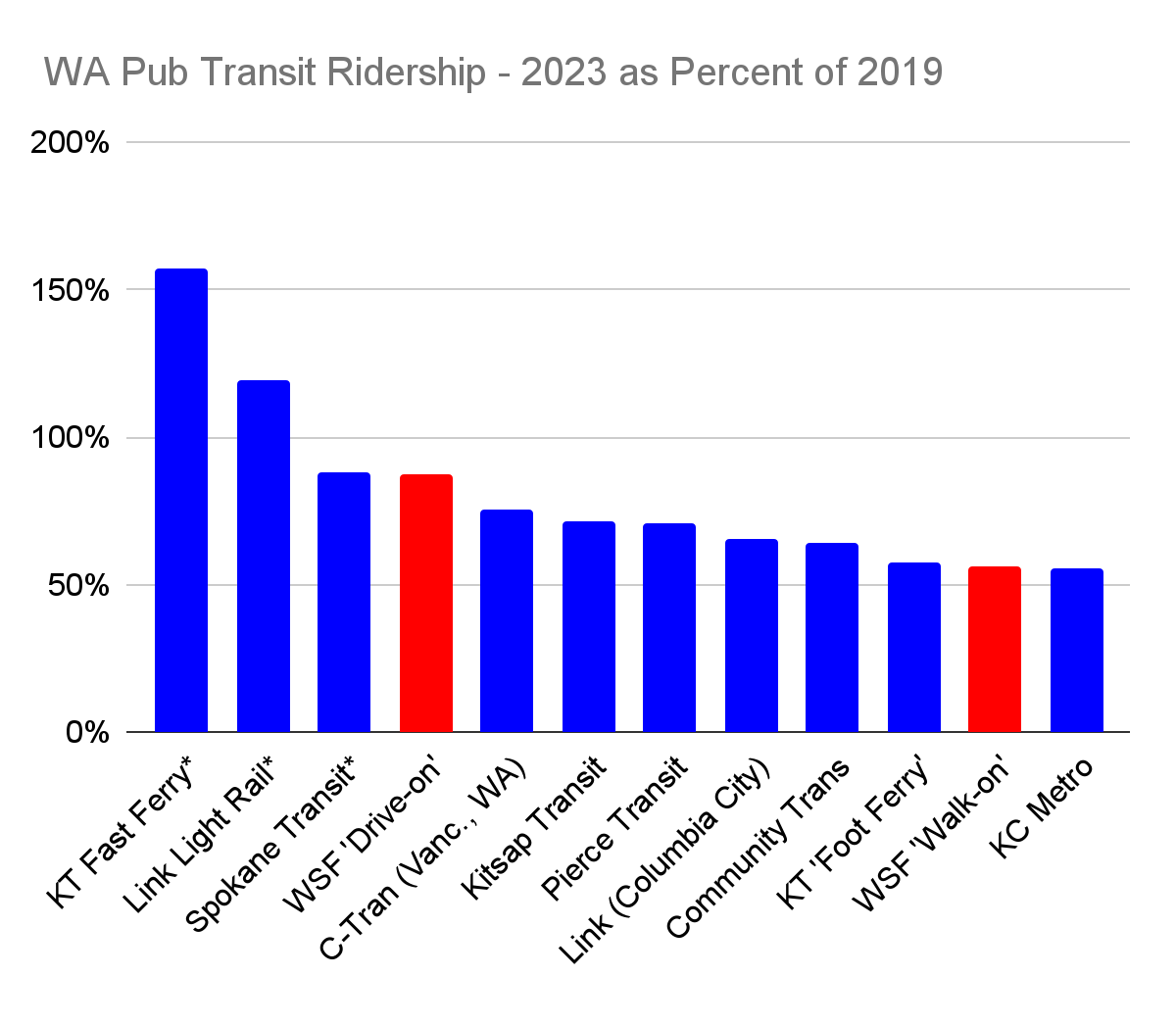

Nationwide, transit agencies saw ridership tumble during the pandemic. But WSF ridership has recovered faster than most. In 2023, WSF ridership has returned to 78% of pre-pandemic (2019) ridership, which is better than almost all other Washington transit agencies. The overperformers all saw significant infrastructure expansions, like Kitsap Transit Fast Ferry additional ferry routes and Link’s additional light rail stations.

While WSF walk-on ridership is down across the board, Bremerton has been particularly badly hit, with walk-on ridership just 28% of 2019 levels. What explains that disparity?

Hypothesis #1 – New fast ferries are poaching riders from WSF

Hypothesis: Riders are choosing zippy, passenger-only ‘fast ferries’ over slower car ferries.

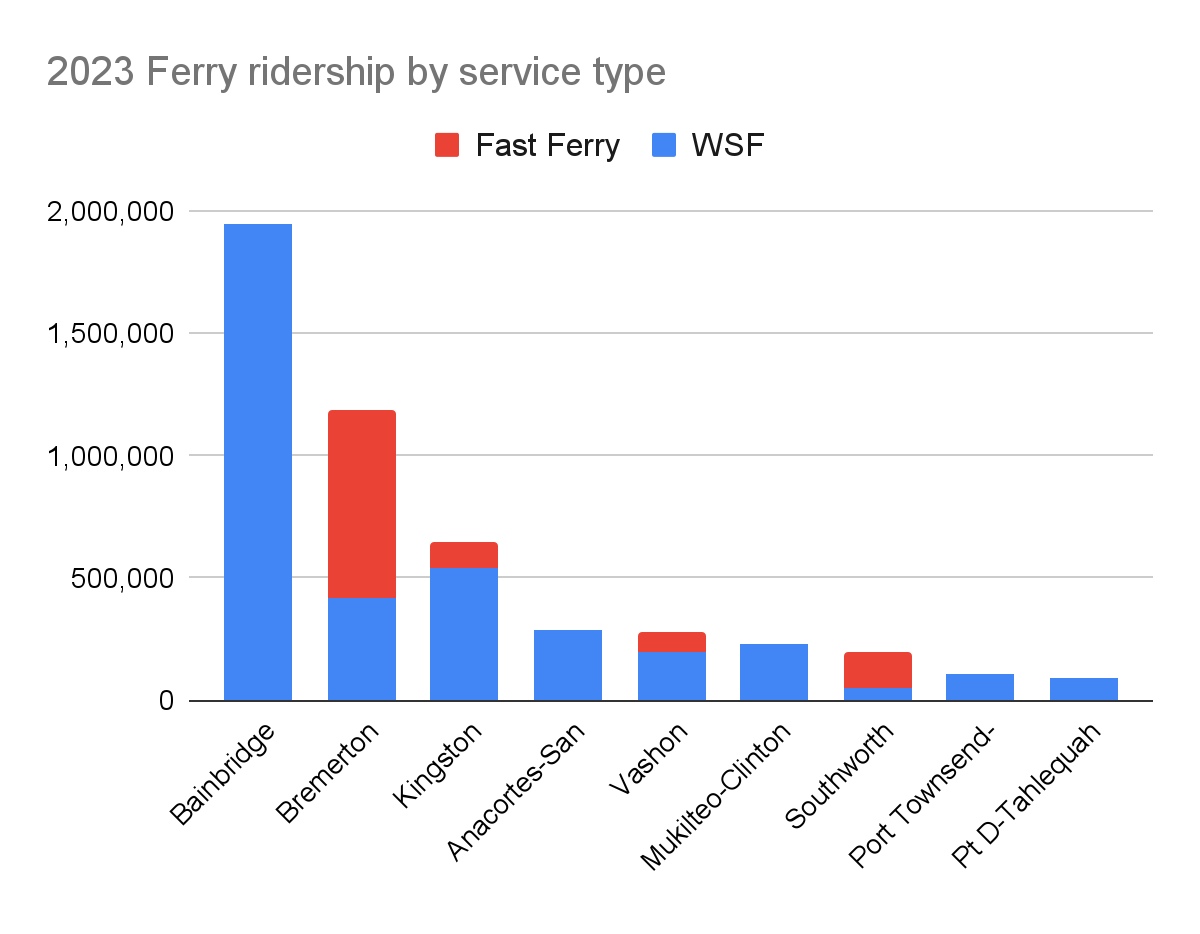

Fast ferry systems – both from Kitsap Transit and King County Metro – have boomed. In 2023, Kitsap’s fast ferries carried 1.1 million riders, 770,000 between Seattle and Bremerton, 106,000 from Kingston, and 146,000 to Southworth – all huge increases over 2019. Metro’s Water Taxi carried 85,000 on the Vashon line and 314,000 on the West Seattle line.

Those combined 1.5 million passengers are equivalent to 50% of the ‘missing’ WSF walk-ons. The Bremerton fast ferry route carries the equivalent of 71% of the 1 million passengers missing from the WSF Bremerton route. In Southworth, the fast ferry now carries more passengers than WSF di before the pandemic

Verdict: The new Fast Ferry systems from Kitsap Transit and King Co Metro are strong competition for the WSF walk-on passengers, sapping WSF ridership.

Hypothesis #2: Work-from-home has killed the commute

Hypothesis: Fewer employers demand rigid five-day, in-office work weeks, meaning fewer commuters riding WSF.

As workers in Greater Seattle are more likely to work from home than the US overall, there’s strong support for this hypothesis. Ranking walk-on ridership of the 9 WSF routes, 4 of the 5 worst recovery rates are on routes that begin or end in Seattle. Bremerton, Southworth, Bainbridge, (Mukilteo), and Vashon. Walk-on ridership is ideal for downtown workers, so reduced in-office attendance reduces WSF ridership. Conversely, ferries to vacation destinations, like the San Juans are much less affected.

Additional support from this hypothesis comes from the days people travel, as weekday (Mon-Thurs) ridership declines relative weekend ridership (Fri-Sun). In 2019, most (57%) of walk-on ridership took place on Mon-Thurs. By 2023, only 49% of walk-on riders boarded on a weekday. For drive-on passengers, in contrast, the weekday/weekend ridership ratio is unchanged 2019 and 2023, suggesting drive-on riders are less likely to be working downtown Seattle.

Verdict: Although it’s tough to quantify with available data, the work-from-home trend has definitely harmed WSF walk-on ridership.

Hypothesis #3: WSF’s canceled ferries reduce ridership

Hypothesis: WSF’s ailing ferry fleet and crew shortages reduce walk-on ridership.

And there’s strong evidence to support this hypothesis. The two routes with the lowest walk-on recovery – Bremerton (28%) and Southworth (35%) – spent all of 2023 with reduced service (one boat less than normal). And when an emergency forces one-boat service on a certain route, ridership drops by 37% until the second boat returns.

Verdict: WSF is unlikely to regain full walk-on ridership before the service is back to full strength.

Hypothesis #4 – Would-be WSF riders are ‘driving around’

Hypothesis: Many would-be WSF walk-on riders are choosing to drive, depending on the distance.

There’s some evidence to back this up. With the completion of the $1.4 billion I-5/SR16 megaproject the ‘drive around’ and cheaper since the Tacoma Narrows bridge toll was reduced by $0.75 per round trip.

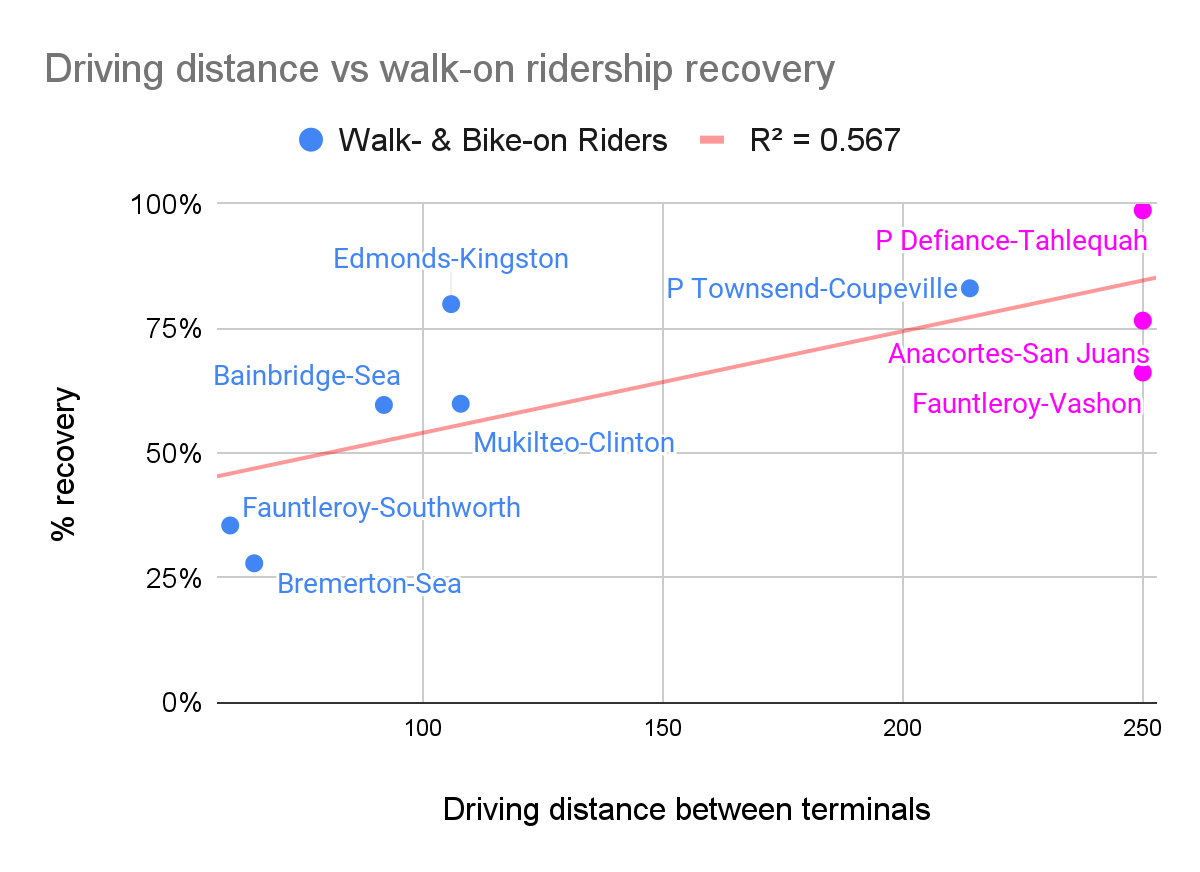

There’s a moderate correlation (R=0.562, r-value measures linear correlation, with R=1 a perfect correlation and R=0 no correlation) between driving distance and low walk-on ridership recovery. Bremerton and Southworth, which have the shortest drives of 65 miles one-way, saw the lowest walk-on recovery. On routes with a longer drive, Edmonds-Kingston is 106 miles one-way, walk-on ridership recovered more. Driving from Island routes (Vashon, San Juans) is impossible, and these routes saw even better recovery, as there’s no other option.

But weirdly, the correlation between driving distance and WSF drive-on ridership recovery is weaker, R-value = 0.289. It seems unlikely that walk-on passengers would be more likely than drive-on to switch to driving.

The $0.75 reduction to Tacoma Narrows Bridge toll likely had little effect on would-be ferry drive-ons, because driving is so costly. If you were a State employee driving your own car, the State would reimburse you at $0.67 per mile, meaning the 130-mile, round-trip between Bremerton and Seattle costs drivers $87. So a $0.75 toll reduction is unlikely to factor much into their transportation choices.

Verdict: The drive-around option became significantly more enticing since the pandemic, especially for relatively close ferry routes with reduced service, like Bremerton and Southworth. But the data does not support the Tacoma Narrows toll reduction as a primary contributor to walk-on passenger reductions.

Bremerton: All hypotheses exacerbated

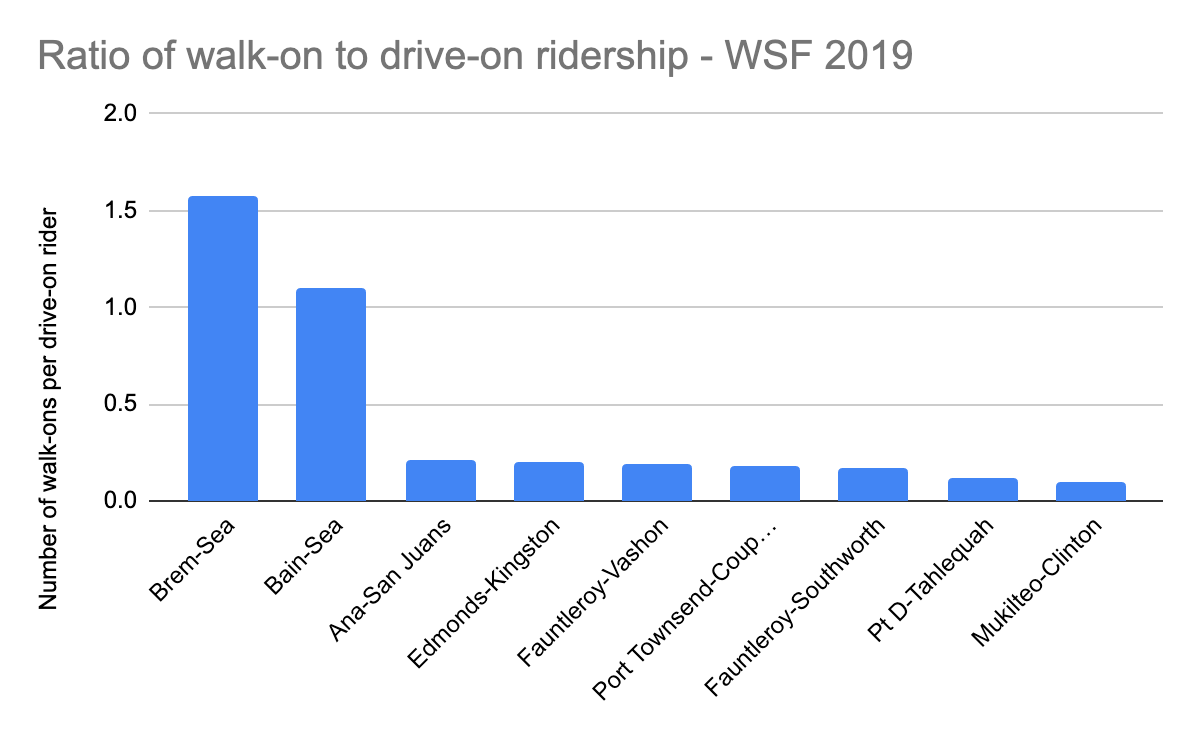

Bremerton stands out for its extremely low ridership recovery. Ridership on the Bremerton to Seattle route is just 28% of walk-ons and 39% for drivers – the lowest recovery rates in the entire system. Before the pandemic, Bremerton accounted for about 23% of all WSF walk-on passengers. In 2023, it was just 11%.

Bremerton exemplifies all the trends above. Bremerton has always had the highest walk-on to drive-on ratio, so trends that affect walk-on we’re bound to affect Bremerton-Seattle more than other routes. And all the hypotheses discussed above affect Bremerton particularly strongly. The drive from Bremerton to Seattle (65 miles) is the second shortest ‘drive around’ of any terminal-to-terminal drive (Southworth to Fauntleroy is 62 miles). Bremerton has, by far, the most robust walk-on passenger system in the Puget Sound, and many more Brem-Sea fast ferry trips than in 2019. Both Bremerton Fast Ferry and WSF take passengers right downtown Seattle, so reduction in downtown office commuting hits ridership hard.

Worst of all, Bremerton has suffered the worst service reduction in the entire WSF system. For over two years, Bremerton has been served by just one boat, the so-called ‘Alternate Service.’ Only nine round-trips per day connect Bremerton with The Emerald City. Naturally ridership is down, as are residents relying on the service. Bremerton is known to carry a chip on its shoulder, and certainly feels singled out by WSF for extraordinary service reductions.

WSF may face a challenge to win back Bremerton riders, even in the distant future when a full, two-boat service returns. And WSF should care about winning Bremerton back. In 2019, Bremerton had, by far, the highest proportion of walk-on to drive-on passengers, contributing less to car-clogged streets and contributing more to Downtown Seattle’s recovery. It’s hard to imagine WSF being ‘fully back’ without reliable service to the heart of Kitsap County.

Can WSF win back walk-on ferry passengers?

WSF will reinforce its aging fleet over the next 15 years, restoring full service to beleaguered West Sound outposts… eventually. Until then, America’s largest ferry service will struggle to compete with faster, less expensive, passenger-only ferries. WSF could improve the ferry experience by responding to customer requests for on-board wi-fi, covered areas for cyclists waiting to board, improved coordination with ferry-to-bus connections and even cheap upgrades like coat racks.

It’s not clear that WSF is incentivized to care about this loss of walk-on passengers. In 2023, only 21% of WSF passengers biked or walked onto the ferry, down from 29% in 2019. And financial incentives encourage WSF to favor drivers because vehicles pay 4.5 times more for a round trip ($44.50) than walk/bike-on passengers ($9.85). WSF considers itself part of the state highway system; the ferry routes are literally state highways. That seems to show up in which riders it prioritizes as well.

All this provides disincentive for WSF to build amenities that could lure walk-ons back. For instance, ferries lack Wi-Fi, and many terminals, including Seattle’s new $489 million Colman Dock, lack sun/rain protection for cyclists.

But WSF should want its walk/bike-on ridership back because they use vastly fewer resources, don’t clog traffic, and support businesses in ferry neighborhoods. Besides, WSF is a proud service, largest in the nation, with roots back to the Mosquito Fleet of yesteryear. And only WSF runs late at night and on Sundays. Bremerton and other West Sound cities badly need WSF to get healthy and thriving. To compete in this new era, WSF will have to do more than just bring full service back. They need to up their game, and I hope they do.