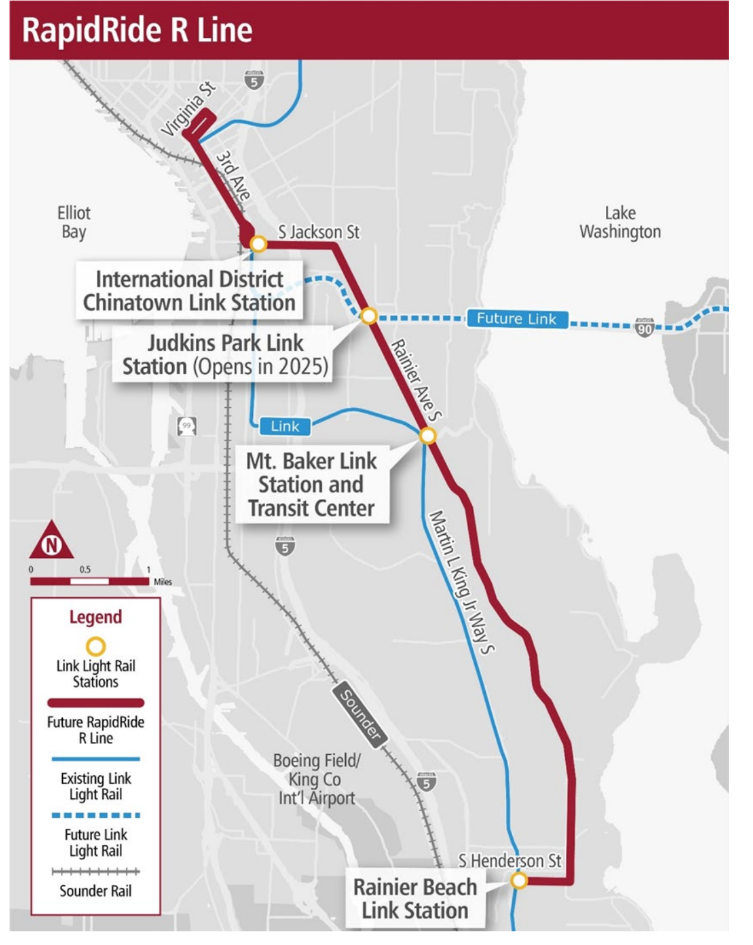

A new report detailing progress on King County Metro’s RapidRide program has revealed that Seattle’s R Line won’t be delivered until 2031 at the earliest. The RapidRide R Line, long-planned to replace today’s Route 7 along Rainier Avenue, has been subjected to numerous funding-related delays, but last year, Metro was still saying a 2028 opening was potentially doable.

The delay illustrates the incredibly long timelines that have become inherent in Metro’s biggest transit corridor improvement program, even as the upgrades consistently bring increased ridership and system efficiency.

The R Line is tabbed as one of only a few signature transit investments in Seattle’s next transportation levy, if the $1.55 billion package is approved by voters this fall. But “RapidRide+” upgrades to Route 7 had been included as a promise to voters in the 2015 transportation levy as well, improvements that were downgraded to spot upgrades after King County put the RapidRide line on hold in 2021 — the year it was also originally pledged to open.

Of the seven RapidRide Lines promised in Move Seattle, only the H Line has been delivered as of yet. When it finally opens, the R Line will be only the fourth of the seven RapidRide lines promised by backers of the 2015 Levy to Move Seattle. Facing a lack of federal grants under President Trump, Mayor Jenny Durkan announced in 2018 that Route 40, 44, and 48 would be getting lesser upgrades, not RapidRide conversions as pledged.

This new timeline means that a Rainier Avenue RapidRide won’t be delivered until the tail end of the new eight-year transportation measure. In the meantime, riders on Seattle’s second busiest bus line continue to face traffic-related delays on the busiest parts of Rainier, and the corridor continues to add hundreds of new homes per year, with major developments like the Grand Streets Commons coming online.

The newly revised timeline doesn’t call for the King County Council to vote on an official route for the R Line until 2026, with design work stretching until 2027 and construction starting in 2028.

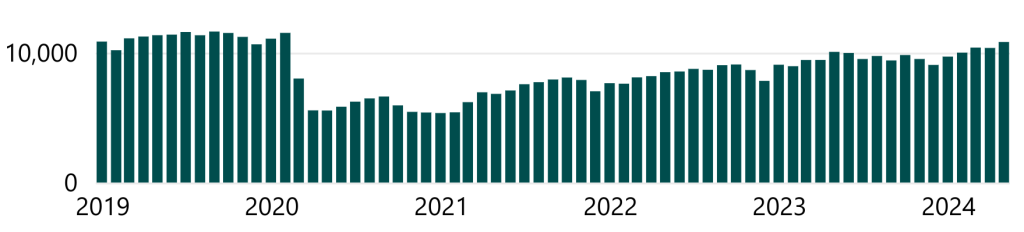

Route 7 leads Metro in ridership recovery

According to Metro, in 2019 the Route 7 experienced more hours of passenger-delay cumulatively than any other route countywide, beating out other infamously delayed buses like the Route 8 and the Route 271 on the Eastside due to its high levels of ridership. Compared to other routes in King County’s network, the 7 saw relatively modest declines in ridership throughout the pandemic, and has nearly regained all of them, with ridership in May of 2024 at 95% of what it was in 2019.

The Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) has implemented some Route 7 improvements in recent years, and is about to lay down the most significant stretch of new bus-only lane that the corridor has seen in years, for northbound buses between Columbia City and I-90. That should improve on-time performance and speed up trips somewhat for riders in the interim, but the most problematic stretch of the route — Rainier Avenue north of I-90 and S Jackson Street — will remain unchanged, at least according to current plans.

The R Line’s long timeline is far from unique. Planning for the G Line along Madison Street, set to open in September, started in 2014. The J Line, set to start construction later this year and open in 2027 or 2028, had its planning phase start that same year. Work on the I Line, which consists of much more modest upgrades and far fewer construction timelines than those lines, started in 2019 and won’t open until 2026. The K Line, Metro’s first new RapidRide line on the Eastside in a decade, is not expected to be delivered until 2030 after going back on the shelf with the R Line in 2021.

Metro staff working on the RapidRide program face considerable headwinds in implementing projects, including local governments who tend to view bus improvements transactionally, extensive environmental review due to federal grant requirements, and a County Council that has made a policy decision to shift most of its capital spending at the state’s largest transit agency to fleet electrification.

Despite clear benefits, RapidRide expansion timelines slip

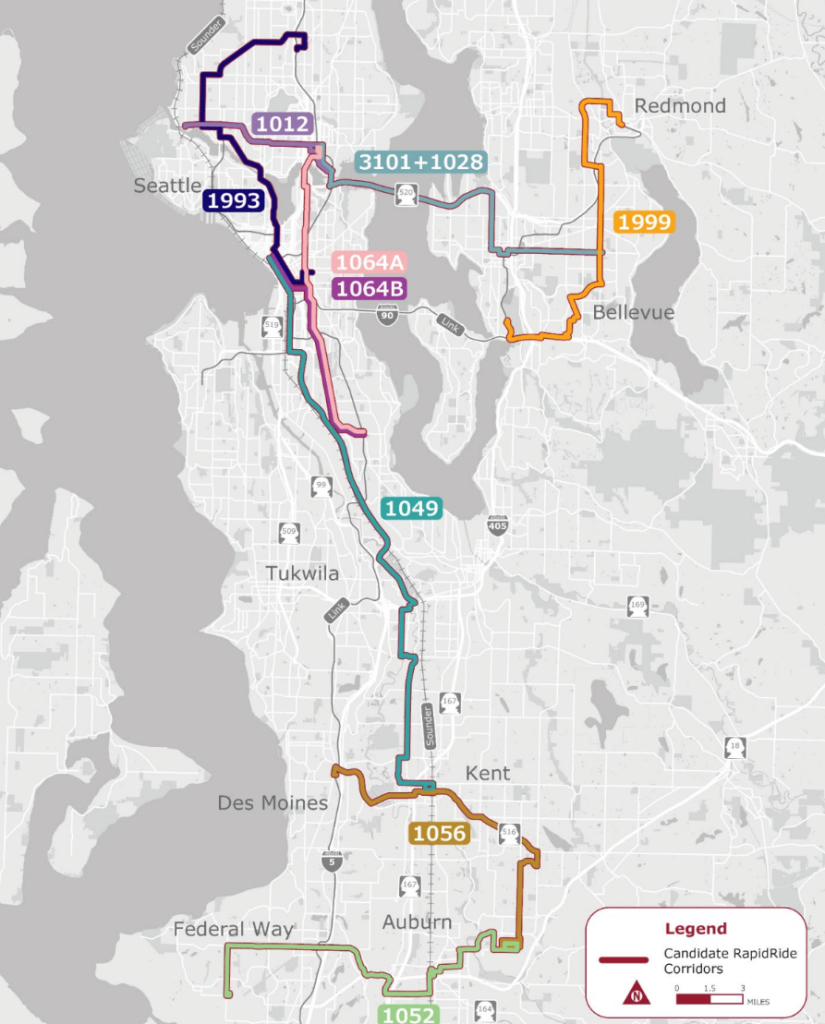

Against the backdrop of the K and R Line getting back on track, Metro has just delivered the results of a RapidRide prioritization study requested by the King County Council in 2021. The report looks at the eight RapidRide corridors identified in Metro’s long-range plan, Metro Connects, that are supposed to be up-and-running by the mid-point of the plan’s implementation, around 2035 as the Ballard and West Seattle Link extensions start to come online.

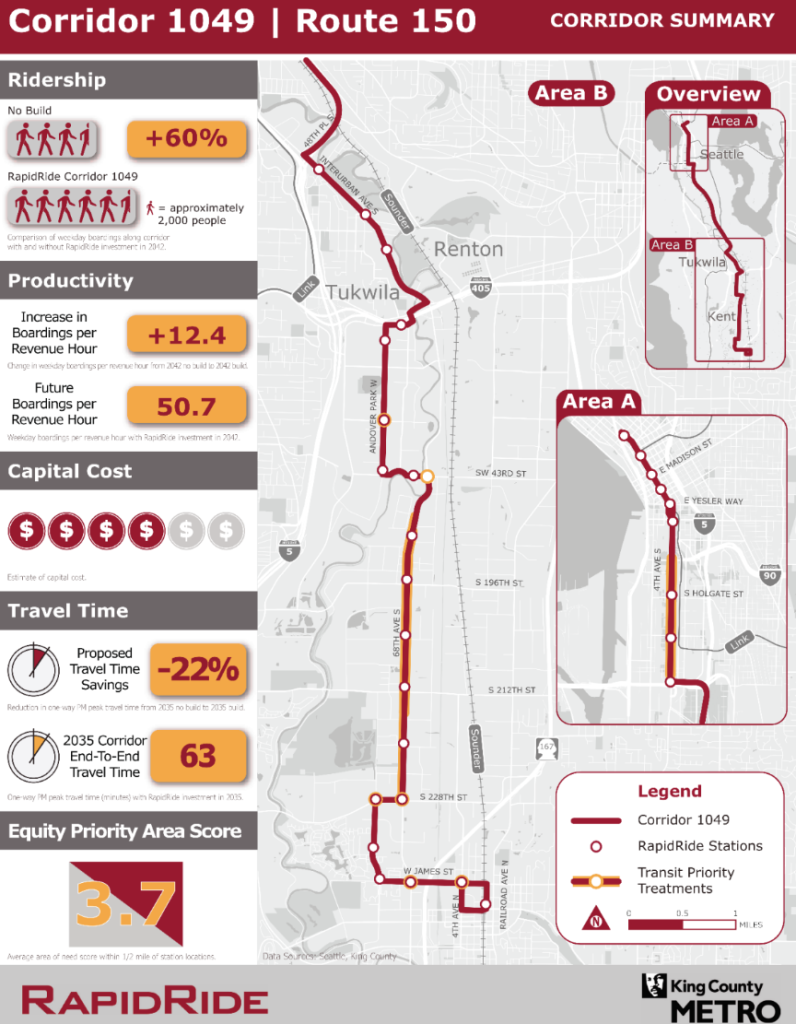

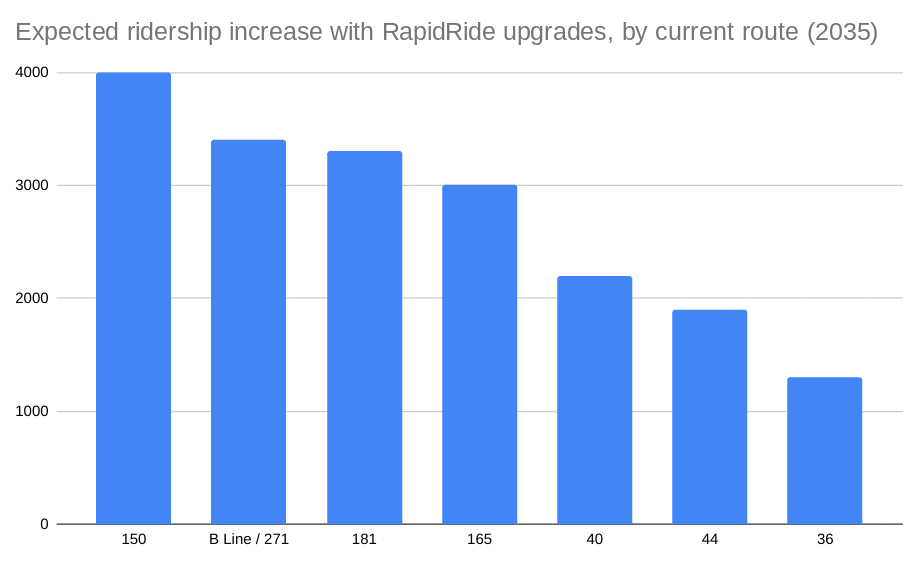

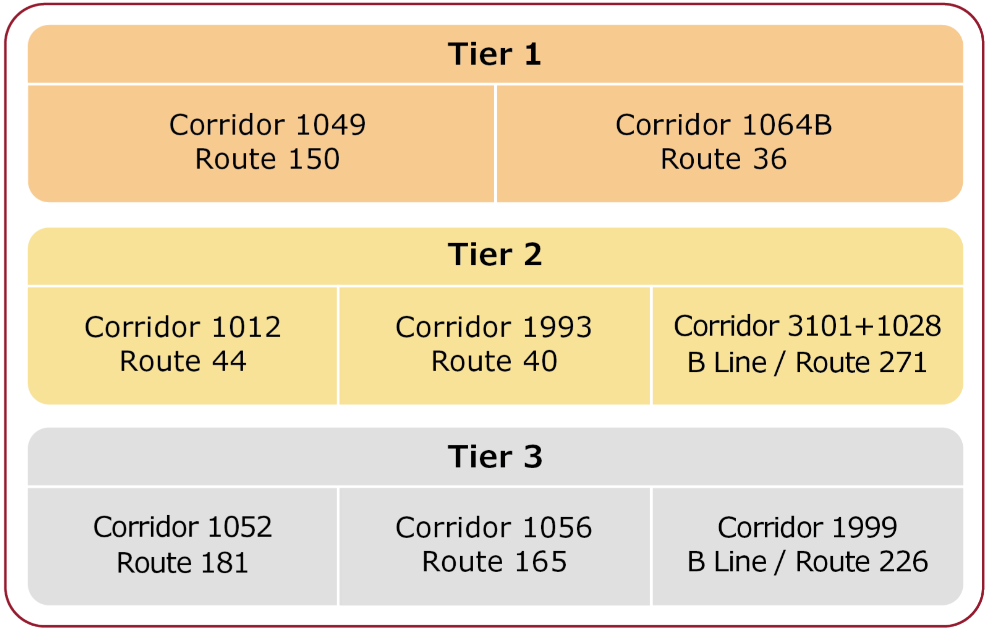

The report does its job of prioritizing the eight corridors, putting the current Route 150 between Downtown Seattle, Southcenter Mall, and Kent and the Route 36 between Downtown Seattle, Beacon Hill, and Othello Station into the tier that would be prioritized for investments first. But what the report really does is highlights the benefits that would come from prioritizing all of them, identifying thousands of additional riders that would be attracted to these corridors if service and reliability improvements were made, independent of potential changes in land use around the lines that are expected to bring new riders as well.

Upgrading Route 150 is expected to add 4,000 additional daily riders by 2035, compared to how many would be riding the route as it exists now without any improvements — a 60% increase. Upgrading Route 181 between Federal Way and Auburn is expected to entice 3,300 additional riders, a staggering 157% increase. Improving Route 165 between Des Moines and Auburn? 3,000 more riders every weekday.

Routes within Seattle would see slightly less riders added with upgrades, largely due to the fact that those routes already have higher usage on a per-mile basis. Overall, Metro projections found upgrading all eight corridors would add more than 19,000 riders every weekday, more riders than Metro’s single busiest bus line.

None of these routes are anywhere close to funded yet. The two “tier 1” routes — the current 150 and 36 — are said to “represent the most important opportunities to advance Metro’s goals,” but it’s not clear how urgently policymakers will see those opportunities.

“Tier 1 RapidRide candidates are the highest priority for development as part of the interim network, but these lines are not currently funded and development would be subject to future available funding being identified through the budget process, as well as delivery capacity,” the report notes. “Tier 2 candidates are next to be developed for the interim network if additional funding or development capacity becomes available.”

The report anticipates punting Tier 3 projects to the 2050 network despite a clear alignment with county and local goals — goodbye, 157% ridership increase for the 181.

Climate plans in doubt

These unfunded projects stand in contrast with Metro’s work on fleet electrification, which is moving full speed ahead. A recent audit by the King County Auditor’s Office cast serious doubt on the agency’s ability to move toward zero-emissions buses at the pace needed to meet its targets, as technology limitations and the inability to find suppliers stands in the way. Those targets are narrowly focused on the issue of bus emissions directly, and don’t take into account the benefits that come from Metro being able to reduce car trips taken by county residents.

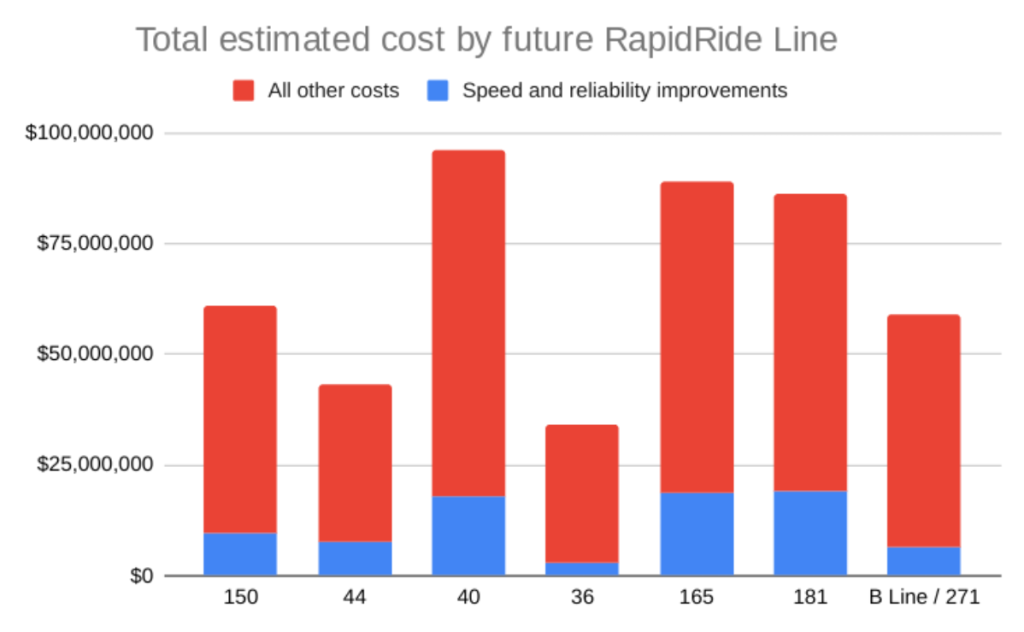

If fully funded, the eight RapidRide lines identified in the report would cost anywhere from $468 million to $513 million, compared to the $782 million that Metro’s current fleet electrification work, which includes four base projects and six layover charging projects. But notably, the report breaks out the individual components of each proposed RapidRide line, with the actual speed and reliability components only ranging from $2.8 million to $19.1 million. While that doesn’t include costs like design and community engagement, it’s clear that even if full RapidRide projects get put on the shelf, the improvements for riders don’t have to.

It doesn’t appear the County has delved into the question of whether a high ridership transit system with fewer zero-emissions buses would mean fewer regionwide emissions than a transit system with zero-emissions buses but relatively low ridership and more people still driving to get around.

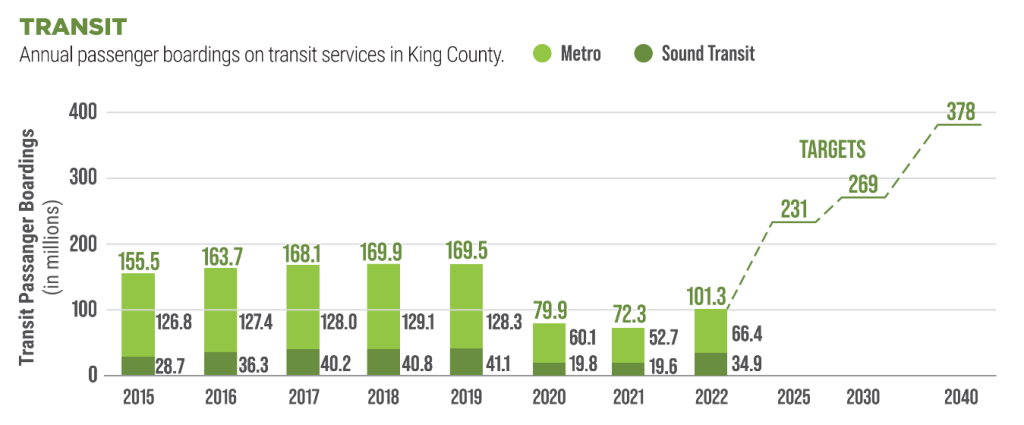

King County’s climate action plan calls for a dramatic ramp-up of transit service and a 20% reduction in car trips (compared to 2017 levels) by 2030, but the county’s trajectory is headed in the wrong direction. The County’s recent progress report called for a “serious course correction” on transportation emissions, and all signs point toward the county needing to find a solution to the long timelines and large project costs associated with the RapidRide program.

King County’s Regional Transit Committee is set to discuss the RapidRide prioritization report at its meeting on Wednesday, July 17.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.