At the end of June, Seattle Mayor Bruce Harrell announced the expansion of the Community Assisted Response and Engagement (CARE) department first responder team, which provides dual dispatch alternative crisis response from behavioral health specialists. The CARE department, which also houses 911 dispatch, is Harrell’s implementation of the oft-discussed idea of a third public safety department working alongside police and fire.

The CARE team first launched in October and currently consists of six first responders who work in teams of two. Thus far they have mainly operated downtown, but with the expansion, that will be changing. The CARE department will hire 18 additional responders and three supervisors and gradually increase its coverage area, with the goal to be citywide by the end of the year.

The first day responding to the East Precinct service area was Tuesday, July 2. The next area targeted for expansion will be North Seattle in the fall.

The CARE teams will respond seven days a week and will be moving to noon to 10pm shifts.

Of the 125 calls the CARE teams answered in April and May, SPD was able to quickly secure the scene and pass the case to CARE workers more than half the time. By contrast, the city received over 20,000 911 calls during those months. The CARE department has also recently secured the ability to give direct referrals to the Crisis Solution Center, something that in the past could only be done by police.

This expansion is being partly funded by a one-time $1.9 million federal grant after being championed by Congresspeople Adam Smith and Pramila Jayapal. While using one-time funding for an ongoing program can be risky, CARE Acting Chief Amy Smith seems optimistic, citing significant philanthropic interest in the project. “My job is to […] speak to the financial efficiency of this,” she said. “This is significantly more fiscally responsible.”

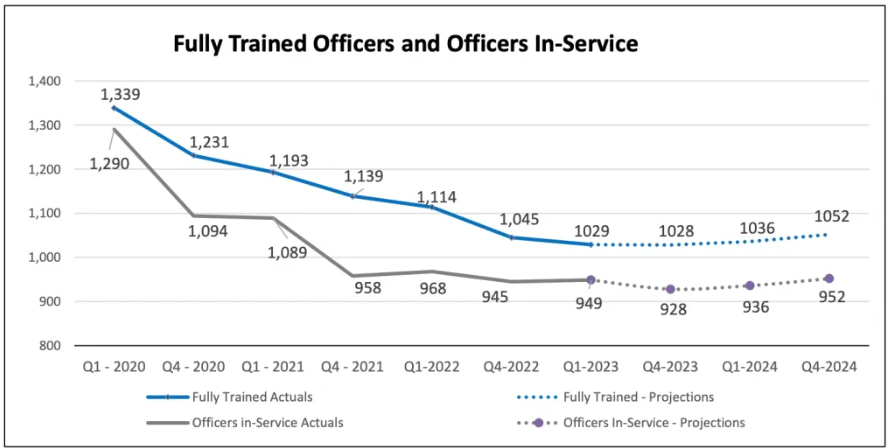

CARE also represents one of the few ways Seattle can increase its capacity to respond to emergency calls in the near term due to declining police officer staffing levels. The Seattle Police Department (SPD) has seen 700 officers leave in five years and has not been able to hire fast enough to replace them. As a result, SPD is at its lowest staffing level in 30 years and response times to all but the highest priority calls have soared.

While SPD staffing levels have declined around 26% between 2017 and 2023, crime rates do not appear to be directly correlated. Over the same period, a Real Change analysis found violent crime rates increased by 8% and property crime rates decreased by 7%.

A new chief

Harrell announced last month he will nominate CARE Acting Chief Amy Smith to serve as the department’s permanent chief, which will require a city council vote to confirm.

Appearing to run on boundless energy and optimism, Smith has spent a lot of time forging relationships: with the Seattle Police Department (SPD), with the Seattle Fire Department, with her peers around the country, with local service providers, and with city government.

“I talk about the value of every life all the time, and the older I get, the more I think it is the luck of the draw,” Smith said. “I’ve learned, whatever I have that is an affordance, to try to use it for good for people who don’t have the same luxury or the same access.”

Smith expresses a strong sense of urgency when she talks about her job. “I’ve seen enough deaths that absolutely were predictable, and they’re avoidable. And so that is the urgency,” she said. “I’m not really interested in spending a lot of time in offices. I’m just trying to make sure that we drive as much change as we can. And we spend most of our time on the front lines, because a lot of [the work] is getting to know someone.”

Ideally she wants to design a flexible first responder system where staff members can flow to the work as needed.

Labor issues abound

One reason for the delayed development of an alternative response in Seattle has been its troubled relationship with labor, and particularly with the Seattle Police Officers Guild (SPOG), which represents SPD’s rank-and-file.

The city has signed two memorandums of understanding (MOU) with SPOG in recent months. The first one said the CARE team can only respond to two call types: wellness checks and person down calls. It established the CARE team as a dual dispatch program, meaning SPD officers are dispatched simultaneously with the CARE team.

The MOU also set an upper cap on the size of the new CARE response program, limiting it to 24 responders. Smith says this limit has been mischaracterized and was actually originally her idea, as she didn’t want to grow faster than she could organize the new response.

Harrell said increasing the size of the CARE response unit is a big priority for the city in this round of bargaining with SPOG. “SPOG understands policing in 2024, 2025, will change, is changing in this country, that coupled with accountability measures,” he said, adding that he feels very optimistic.

The second MOU with SPOG, agreed upon in May, places additional restrictions on the CARE team’s response to wellness check calls.

Smith is clear on her position that the role of labor in conversations about alternative response needs to be reimagined. “What’s happened, especially in public safety, is that there’s not flexibility to run the business, right? To rapidly iterate,” she said. “You have to pause and then renegotiate. It takes a long time, and it’s expensive.”

Labor rights are important, but those suffering should come first, Smith argued. When discussing a potential labor negotiation over whether CARE or community service officers (CSOs) are allowed to give someone a ride, she said, “In no world should the CSOs pass by someone in crisis and not give the ride because CARE gets to give the ride. That cannot be a body of work issue.”

Determining who gets the first right of refusal for such a task may be a worthy labor bargaining topic, but Smith repeated, “People suffering cannot be a body of work issue. That is part of the problem here.”

“We shouldn’t be in service to ourselves,” she continued, “especially in first response. We should care more about that person.” Smith believes labor agreements can be reached because “nobody wants folks to suffer and die on the streets.”

Eventually Smith would like to see civilian first response legislated at a federal level just like 988, mandating that cities of a certain size and with a certain call volume have a new first responder unit. This, she believes, would be preferable to having the existence of these programs depend on political sentiment. “It’s just the right thing to do by the data,” she said.

Dual dispatch and call types

Given the choice, Smith said she wouldn’t have set up the CARE response team as a dual dispatch program. “I absolutely would have set it up like Durham or Albuquerque, because I would have had that bias toward first response and quality assurance and improvements,” she said. The civilian first responder system in Albuquerque is dispatched directly from 911 to calls that don’t indicate any immediate threat or danger.

In contrast, thus far only 12% of the CARE team’s calls were dispatched from the 911 center, while the remaining 88% were referrals from SPD officers. Last March The Stranger reported the CARE team appeared to be underutilized, and Smith specifically mentioned that the CARE team only responding to two to three calls a day is unacceptable,

But Smith expects this to change, noting that sergeants can simply elect to have the CARE team respond to any given call instead of officers, a procedure that has been included in the most recent training videos but depends to a certain extent on SPD officer buy-in around the CARE responders. She also wants to retrain dispatchers who are used to defaulting to sending a police response.

At the city’s late June press conference, she said about half of calls could be responded to with a civilian response, a number also backed up by the 2021 National Institute for Criminal Justice Reform (NICJR) report that found 49% of Seattle’s 911 calls could be answered by civilian response and another 24% could be answered by a civilian and police team led by the civilian.

She also said it was wrong to focus too much on call types, saying they misrepresent what a call really is. Instead she emphasizes a single question: does this call require a responder who has a gun and a badge?

“That is the primary question,” Smith said, “because that is what I think has caused a lot of suffering, and over policing, policing of social issues, and it’s just so cynical. I do recognize we have escalating violent crime. But I think the solution to that is better early intervention, diversion, and prevention. And then, you know, folks who are very far downstream right now, I reserve police for that.”

Smith suspected 911 dispatch was upcoding to classify every call a priority one or two because otherwise the police wouldn’t go, and she was able to confirm that this was in fact happening. Work began in December to simplify the hundreds of call types currently used by 911 dispatch, which has included eliminating some call types entirely.

One of the goals of the work is to alleviate the burden on officers, an ever-present concern as SPD announced recently that they’re on track to once again lose more officers than they can hire this year. This will be the fifth straight year SPD will experience a net loss of officers. The last year they hired more officers than they lost was 2019, although they also lost more than they hired in 2018, pre-dating the Covid-19 pandemic. A report shows the loss in 2018 was driven by many factors, most prominently higher retirements and more younger officers who didn’t live in Seattle leaving to be police officers elsewhere in the region.

Meanwhile, Loren Atherly, SPD’s senior director of performance analytics and research, is hard at work on a machine learning tool that uses AI to analyze 911 calls, giving each call a stability rating as to which type of response the call should receive. If there is a role for AI in 911 dispatch, Smith says they “haven’t quite figured it out,” but she does believe it might be able to reduce tension throughout the system.

The future of CARE

Smith is very optimistic that in five years, Seattle will be really far down the road towards having an effective alternative response while being able to focus more on diversion and re-entry services as well. She mentioned an Office of Violence Prevention that Harrell is considering establishing in order to organize all the city’s prevention services under a single umbrella.

“I know through firsthand experience, but also just through the lens of cognition, anyone can change,” Smith said. “We’ve got to start there. And then if it looks like this is not a system where somebody’s going to experience positive change? Reform that system.”

Smith is hard at work doing just that, in spite of the many budgetary, labor, and operational obstacles standing in her way. Only time will tell if she’s able to achieve her vision for Seattle’s third public safety department, but she seems determined to do everything in her power to make it happen.

“I am working for this person dying on the sidewalk,” Smith said. “Somebody has to.”

Amy Sundberg is the publisher of Notes from the Emerald City, a weekly newsletter on Seattle politics and policy with a particular focus on public safety, police accountability, and the criminal legal system. She also writes science fiction, fantasy, and horror novels. She is particularly fond of Seattle’s parks, where she can often be found walking her little dog.