A City of Seattle advisory board voted last month to advance amendments to the city’s energy code walking back energy efficiency requirements in large buildings scheduled to take effect this fall. The changes, which have been pushed for by the Harrell Administration, were proposed in an attempt to reduce costs for multifamily home construction. Harrell officials contend that this is necessary to respond to a sharp downturn in new permit applications from builders, who have complained of high interest rates and mounting regulatory costs. It will be up to the Seattle City Council to consider the proposal and potentially amend it before it can take effect.

The changes would largely align Seattle’s energy code for new apartments and commercial buildings with the Washington State energy code, creating more consistency for builders across jurisdictions and potentially ending a nearly two-decade run of the City of Seattle’s energy code being more stringent than the state’s by design. In some areas, Seattle’s code would still go further, including with a requirement that all new commercial kitchens be ready to make the transition to all-electric.

Among the provisions in the new code, which is referred to as the 2021 code, that wouldn’t take effect: requirements that 20% of windows in new buildings include expensive triple-glazing, and others limiting the overall size of windows. HVAC systems would be required to be even more energy-efficient than they already are, and the amount of wattage produced by a building’s lighting systems would have been required to be reduced by another 5%. The city code already requires a 5% lighting energy reduction beyond the state code.

These requirements would only impact new office or large multifamily buildings, with single-family homes, duplexes, and accessory dwelling units covered under the less restrictive residential building code.

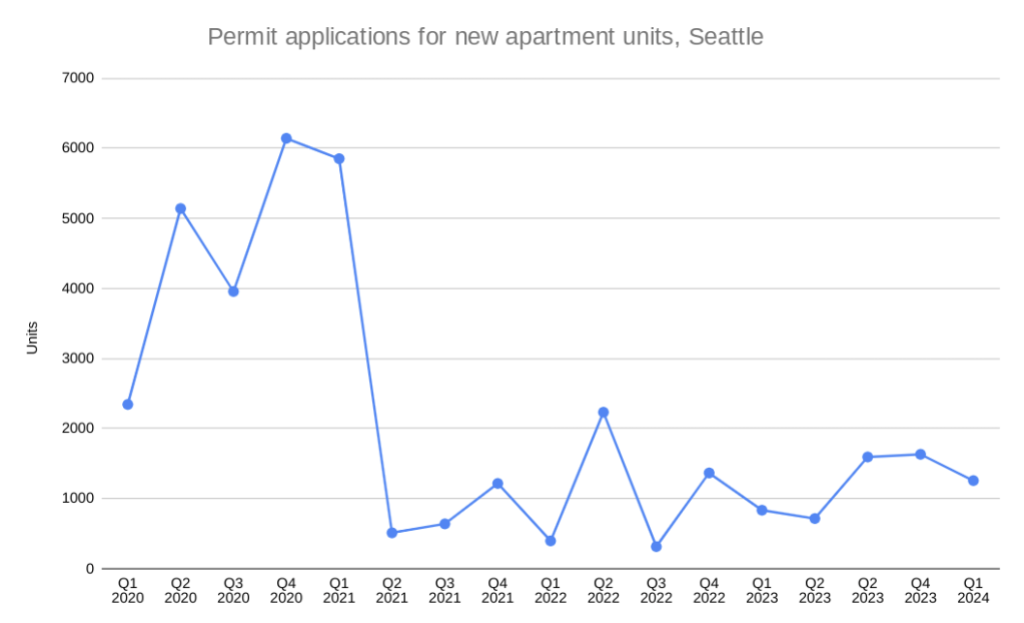

After the last update to Seattle’s energy code, the 2018 code — which did not actually take full effect until March of 2021 — the city saw a big drop in new permit applications as builders rushed to submit ahead of the deadline. Those applications have stayed relatively low, with projects hindered by high interest rates that have impacted homebuilding nationwide. This drought has housing advocates concerned about an increase in housing costs in Seattle in the coming years even as new units are coming online relatively robustly right now.

“We’ve heard from builders of homes, both affordable and market-rate, that there’s many things the City does that can make it harder to build our desperately needed housing,” Seattle’s Chief Operating Officer, Marco Lowe, said in introducing the proposal in May. “We’re working on many different fronts, but one of the things we’ve heard is that that city energy code, when it first exceeded the state code, was a really necessary important step that led the way, but then over time as it’s become more and more efficient, […] this may be becoming something that we were hearing from building developers that was making it harder for projects to pencil.”

Washington State’s energy code had previously lagged significantly behind Seattle’s, with a 2001 Seattle City Council resolution explicitly requiring the city energy code to be more stringent than the state in an attempt to pull it along. But the current state energy code is widely recognized as one of the most robust in the country, with Washington the first state to mandate that heating and cooling systems in new commercial and multifamily buildings be all-electric. Going further than the state code, builders say, is adding costs that are out of alignment with potential gains.

Stepping off the regulatory accelerator would represent an acknowledgement that requiring buildings in Seattle to be more energy efficient than elsewhere in the state could be having unintended consequences, making it more attractive to build outside the city. Meanwhile, many suburbs have an energy grid that is more carbon intensive than Seattle’s and transportation infrastructure that is also lagging. Development where transit and accessibility is lacking encourages car use, creating more climate pollution.

“You don’t have to create this weird incentive where you move housing out of Seattle very many times before you offset all the benefits you have from being a leader,” A-P Hurd, the president of SkipStone, a development consultancy firm, and the co-author of the book The Carbon Efficient City, told The Urbanist.

Hurd’s analysis of the current Seattle energy code suggests compliance costs add around $24,000 per unit compared to the state code, with the end result buildings that are more energy efficient, but don’t actually save carbon emissions thanks to Seattle City Light’s net-zero energy grid. Modelling on that code showed a 15% reduction in building energy, though those gains have not necessarily materialized in all cases because the introduction of heat pumps into new units encourage residents to take advantage of the ability to utilize air conditioning. Most apartments in temperate Seattle do not have air conditioning.

“As I look across all the emissions in the city, and all the priorities we have around building performance, transportation, emissions, putting people near light rail, making sure that we have equity around housing opportunity in Seattle, it’s put me in this kind of funny position of now, saying, maybe we’ve squeezed enough juice from this particular orange,” Hurd said.

Some environmental advocates argue that the City isn’t being data-driven enough in its methodology, instead simply responding to a blanket request from the real estate industry.

“It has felt throughout this process that there is a false narrative of this code versus housing affordability,” Deepa Sivarajan, a local policy manager with Climate Solutions, told the board ahead of the final vote. “And one of the frustrations has been that all of the data that we heard about, costs and cost increases, have not been about this code approval. They’ve not been about the measures that have been stricken from last year’s version of the 2021 code, they’ve been about the 2018 code.”

Meanwhile, some members of the development industry have alleged that builders are crying wolf about the impact the proposed changes will have.

“I would say that every cycle, there is kind of a very similar discussion, where the thought is that the changes are going to be incredibly expensive, they’re going to make development very difficult. They’re gonna make housing expensive. And at least from what I’ve seen, in architecture, very quickly, the developers, the builders, the designers, the city, they figure out how to make work,” said Nick McDaniel, a senior associate with the architecture firm NBBJ, said in May. “In my opinion, the proposed change represents a really dangerous rollback of progress on carbon, and on energy.”

However, affordable housing providers have praised the change as striking the right potential balance, noting that it will build on policies already adopted that will make existing buildings in Seattle more energy efficient.

“We are deeply committed to both addressing the urgent housing shortage in our city and advancing environmental sustainability in the built environment,” the Housing Development Consortium’s Laura Frankie said. “We collaborated with the City to pass the landmark building emissions performance standards, or BEPS, legislation, bringing together the stakeholders to craft ambitious policy that will de-carbonize all large multifamily and commercial buildings while ensuring the policy works for affordable housing operators. We believe that the proposed revisions to the energy code will build on BEPS and help create more affordable and sustainable city.”

The Seattle Construction Code Advisory Board (CCAB) did also vote to advance potential amendments that could add additional city-specific requirements, refining efficiency requirements beyond the state code. Those are likely to be hashed out at the Seattle City Council’s review of the policy at the Land Use Committee in late summer or early fall, but every individual amendment reduces the impact that could come from Seattle largely adopting the state code for the sake of making it easier for builders to source materials and complete projects efficiently.

With much more public scrutiny as the proposal heads to council, it remains to be seen how city leaders will thread the needle.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.