Sound Transit is facing numerous project delays and cost escalation issues, and one big reason is that policymakers have designed the system that way. Cumbersome local permitting processes complicate projects and slow timelines.

Agency boardmembers have a narrow opportunity this month to reduce some of Sound Transit’s permitting problems through revisions to its internal betterments policy — project elements that are added beyond the basic scope of a project. But it won’t be enough to alleviate the issue, because of the broader permitting issues Sound Transit faces as it deals with dozens of Balkanized local permitting authorities to complete projects. That’s why Sound Transit’s governing board should be calling for state-level action to exempt the agency from nearly all local permitting processes and making it easier to build in public streets, thereby expediting projects that voters have approved.

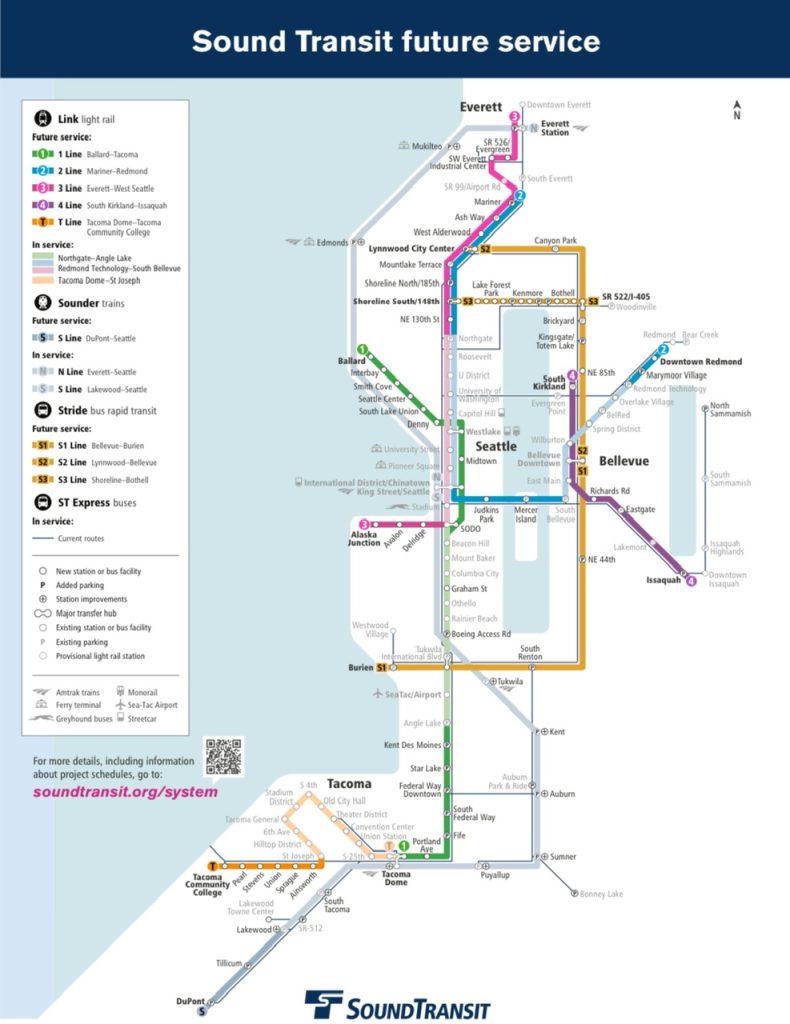

As it stands, transit expansions keep falling farther behind schedule, with budgets ballooning in the process. Sound Transit estimates that every year a project falls behind schedule, costs rise another 3% to 4% due to inflation — consistently outpacing monetary inflation. Ballard Link is four years behind schedule, with the line slipping to a 2039 opening. The Tacoma Dome Link Extension is delayed five years from its original schedule. Even I-405 and SR 522 Stride bus rapid transit projects — intended to be a quicker-build alternative to light rail — have been delayed four to five years.

Continued permitting and approval stumbles will push many of these projects even farther behind schedule and over budget. Local permitting issues aren’t solely to blame for these delays, but it certainly has not helped. Sound Transit’s governing board should be doing everything it can to streamline the process and avoid regulatory quagmires.

Local permitting overly-complicates long linear projects

When Sound Transit carries out light rail expansion, it has to work with local governments. In the example of the Tacoma Dome Link Extension, that would mean Federal Way, Milton, Fife, Tacoma, and Pierce County — to obtain various permit approvals in each. Many communities, particularly smaller and suburban ones, lack the kind of expertise necessary to review civil engineering drawings and building plans for complex infrastructure and facilities that Sound Transit builds.

Sound Transit has accordingly built out a partnering agreement program, whereby the agency outlines a broad scope of tasks that partner local governments will carry out well ahead of formal submission of permit applications in exchange for pledged payments by Sound Transit to fund local government staffing. As part of this, the agency is able to coordinate with specific staff members at local governments throughout the life of a project and is supposed to get expedited permitting when the time comes.

In practice, it’s not evident that local partnering agreements have materially improved Sound Transit’s processes on major projects — projects that continually fall further and further behind schedule and see costs rapidly escalating. Worse, they may be empowering local governments to find new ways to create additional problems for the agency.

Dealing with so many local governments creates numerous headaches for Sound Transit. Because a project needs approvals by every local government along its linear corridor, each respective section is subject to special scrutiny by local government administrators. That means Sound Transit needs to get separate approvals for locally adopted stormwater codes, fire codes, building codes, energy codes, and land use codes in addition to right-of-way permits, leading to the agency obtaining hundreds if not thousands of permits for most projects of significance.

While local construction codes tend to have similarities since they are based upon statewide codes, the application of them is not always equal due to local rules and interpretations of locally adopted construction codes.

On top of this, local land use laws are highly divergent. Sound Transit simply wants to obtain construction permits for their projects, but local land use laws force the agency into lengthy and contentious discretionary permitting processes and compliance with any adopted land use regulations specifically implicating its transit projects. Local government land use regulations can really run the gamut, such as requiring:

- Compliance with local design regulations and review;

- Specific types and amounts of station and site features;

- Setbacks and buffers, height limits, and floor area and lot coverage limits for facilities;

- Minimum parking requirements;

- Open space requirements; and

- Unrelated off-site improvements.

That’s not to say all of those things are bad; on the contrary, some create tangible public benefits. But they are emblematic of how Sound Transit can get stuck in widely varying regulatory processes, and how jurisdictions can take advantage of Sound Transit’s weak position as an applicant.

Beyond land use permitting, Sound Transit projects interface with other public rights-of-way, either because projects are directly located in public rights-of-way or there is some other impact to them. Consequently, Sound Transit has to obtain various types of rights-of-way permits to upgrade utilities, improve pedestrian facilities, and directly use rights-of-way, such as for elevated guideways and stations crossing streets. This opens up another opportunity for local governments to impose special conditions and standards.

Immediate frontage improvements for things like sidewalks and bike lanes at stations and maintenance bases and replacement of most impacted rights-of-way assets may have a place in Sound Transit’s projects, but these shouldn’t be discretionary processes and require formal permitting if basic standards are met by the agency. They also shouldn’t be an opportunity for local governments to get Sound Transit to add or rebuild arterial car capacity.

Mandatory processes already serve local interests

To be sure, another layer of process mostly precedes local permitting.

Required by federal and state law, nearly all Sound Transit projects go through environmental review under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) and State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA). These processes mandate that Sound Transit evaluate potential impacts from its projects on various topics (e.g., aesthetics, air and water, historic and cultural preservation, and transportation), consider alternatives, and provide mitigation measures where deemed warranted.

Fundamentally, these environmental review processes allow for the public and local governments to raise issues for study and then exact concessions in project design and local improvements. In many ways, these processes already serve as a large bite at the apple by local governments to get things that they want. Allowing them to further impose additional regulatory processes keeps giving them more opportunity.

Nevertheless, local jurisdictions keep stacking up more process. For instance, Sound Transit has been deeply challenged in getting its Stride bus rapid transit projects done, in part because of local government permitting roadblocks.

Lake Forest Park residents and politicians have strongly opposed the scoped Stride S3 Line project because it would require some removal of trees through the community, new retaining walls, and private property acquisition. In response, the city council adopted new permitting standards last year with the specific purpose of complicating the project, directly adding to its delays and costs. Over a year later, the city continues trying to meddle and delay the project. Likewise, the Bothell bus base for Stride vehicles has been mired in process to resolve an esoteric land use policy issue that could have been addressed quickly and virtually for free by the Puget Sound Regional Council or City of Bothell alone.

These aren’t isolated instances. As Sound Transit tries to move forward with regional expansion, more and more of these kinds of issues keep cropping up and it now seems a fact of life that new local processes will keep being invented, if left unchecked.

It doesn’t have to be this way, however.

There is a better way forward

In Ontario, Canada, a statutorily-commissioned transit agency called Metrolinx has unique powers over its infrastructure projects in order to complete subway expansions in the Greater Toronto Area in a timely and cost efficient manner. The provincial government passed special legislation in 2020 to both guard planned subway corridors from contrary development activities and preempt local governments from interfering in development and construction of the corridors through permitting processes. Permitting authority is therefore left up to the agency and provincial government in most cases instead.

Likewise, in Québec, Canada, the provincial government passed legislation in 2017 granting special permitting powers for construction of the REM (Réseau express métropolitain), a light metro rapid transit network being built out in Greater Montréal. For instance, whenever there is a need to construct grade-separated portions of the REM over public streets, REM’s provincially-owned agency is guaranteed local approval for permits within 60 days. Failure of a local government to issue an approval within the allotted time period consequently grants automatic approval to use public streets as REM’s operator sees fit and without any compensation to the local government.

Exempting Sound Transit from local permitting also isn’t an entirely new topic in Washington. Back in 2018, Democrats in the Washington State Legislature were trying to adjust car tab fees over fears of a taxpayer revolt. Any adjustment of the fees would have negatively impacted Sound Transit’s financial plan due to reduced funding, functionally leading to delayed projects.

To partially mitigate financial impacts to Sound Transit, Senator Marko Liias (D-Edmonds) proposed various amendments to either limit local permitting timelines or exempt Sound Transit 3 projects from county permitting requirements altogether. Those amendments saw success in the car tab fee legislation, but the full legislation ultimately failed to pass the state legislature. Nevertheless, there was a moment where streamlining permitting processes for Sound Transit had some real political support from state legislators.

Ultimately, local permitting processes do not add much value to Sound Transit projects. More often than not, they simply slow projects down — sometimes to a near-halt — and heap new costs onto Sound Transit. The agency already has comprehensive design and construction standards and voters have repeatedly approved Sound Transit expansion projects, giving their consent to the full scope of the Sound Transit 2 and 3 programs. There’s no reason to keep bogging down agency capital expansion programs.

It’s time for state action to give Sound Transit its own permitting authority and expedite projects that voters have approved, and it’s time for the Sound Transit Board of Directors to demand it. That means exempting the agency from all local permitting under construction and land use codes, and granting the agency an unencumbered and free right to use all local public rights-of-way as it reasonably sees fit.

This is not unprecedented. If we are serious about completing Sound Transit 3 and embarking on the next generation of transit expansions, permitting reform is a must.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.