Transportation Chair Saka’s goal of 500 blocks of sidewalks in five years likely isn’t achievable without more funding and broader changes, according to SDOT.

The Seattle City Council is heading toward a final vote on the city’s next transportation levy, sending a package that will fund nearly a decade’s worth of transportation investments to voters in November. Over the past few weeks, no topic has been highlighted more by councilmembers more than the issue of filling in Seattle’s missing sidewalk network. With around 13,500 blocks citywide missing sidewalks — 27% of all city blocks — most of the city council, including its six brand new members, have touted this levy as an opportunity to make a significant dent in that number.

Next week’s committee vote on amendments will likely be pivotal in determining what those investments actually look like. So far, much of the conversation has been detached from the reality of sidewalk construction on the ground. As with other construction projects, sidewalk costs have been climbing and competition for contractors and labor is stiff.

When transportation committee chair Rob Saka introduced his proposed “chair’s amendment” in late May, increasing the total amount to be collected over eight years to $1.55 billion, a full $63 million of an additional $100 million was earmarked to go toward new sidewalks, and their lower-cost “alternative walkways” — a doubling of the amount proposed by the Harrell Administration. It was initially unclear how many blocks that would enable the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) to build, but when the text of the amendment was fully drafted, it included the expectation that 530 blocks would be the new baseline to complete by 2032, with at least 500 of those blocks “complete or in construction” by the end of 2029.

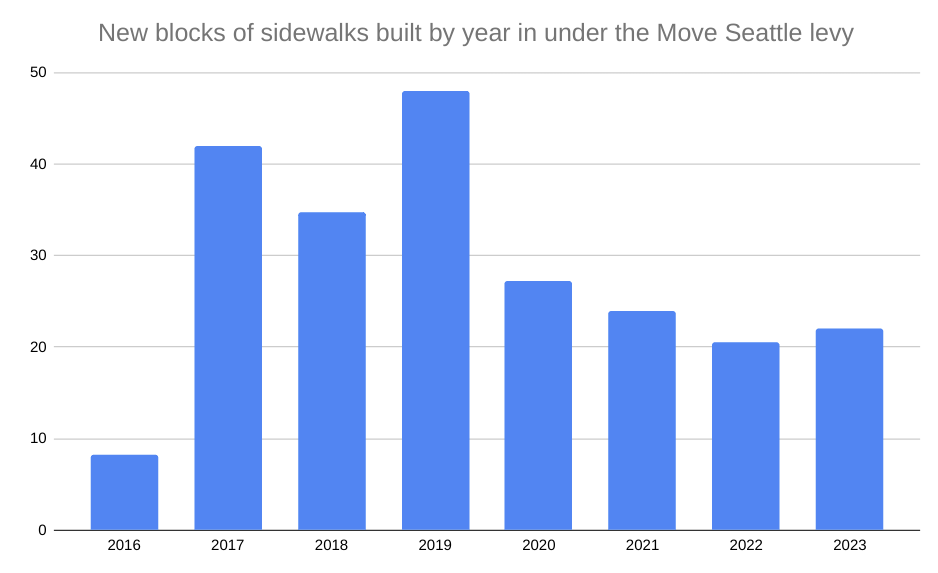

That pace of 500 blocks of new sidewalks within five years would represent the fastest rate of new sidewalk construction in Seattle in decades, and it would require the city to more than double the fastest rate of completion that it saw during the current Move Seattle Levy, approved in 2015. In 2019, 48 blocks of new sidewalks were completed, but the average over the entire levy so far has been less than 30 blocks annually. The city is on track to meet its original commitment to voters of 250 blocks over nine years, but will not significantly exceed that.

The final levy proposal that the Harrell Administration transmitted to the city council included a commitment to build 250 blocks within the first four years of the levy, still a big increase in the pace of sidewalk construction, but one that SDOT is apparently ready to handle, given the improvements that the department has been making around project delivery in recent years.

Another issue with the 500-block promise is the funding itself — Saka’s proposed funding level may not even be enough to actually pay for all of those blocks. With $126 million in levy funding, the average cost per block would be just over $230,000, well below the current average per-block cost. But levy dollars are not the city’s only source of sidewalk dollars. Over the past nine years, levy funding has only accounted for just over half of new sidewalk funding, with dollars from the city’s school traffic zone cameras (31%), real-estate excise taxes (7%) and grants (10.5%) making up the difference.

The fact that other funding sources do not automatically scale up as levy funding increases is why simply doubling the amount allocated to sidewalks doesn’t necessarily result in a doubling of the number of sidewalks that could be built. A 500-block pledge could push council to boost sidewalk funding from other sources at a later date. However, the Move Seattle Levy also provides several examples of overly ambitious pledges fizzling out without intervention, such as the pledge of seven RapidRide bus lines by 2024 being cut in half and delayed.

New sidewalks can vary wildly in terms of costs per block: a new asphalt path separated by precast concrete barriers can cost as low as $200,000 per block, but a new block of permanent concrete sidewalk can come in anywhere from $500,000 to $800,000, and potentially more. Despite getting a briefing on the realities of sidewalk construction in March, councilmembers have drafted amendments that seem somewhat pie-in-the-sky.

SDOT spokesperson Ethan Bergerson confirmed that the department wouldn’t be able to commit to meeting the expectation that Saka laid out, because the city still assumes that only $40 million in local dollars, along with some other project funding like dollars for Aurora Avenue safety upgrades and a repaving projects, will be available for new sidewalks. “The increase of levy funding by $63 million would not fully fund 500 new blocks of sidewalks because of these other funding sources staying constant. SDOT is working on an estimate of the new sidewalk blocks that could be built with the additional funds without knowing the specific locations and their design conditions,” Bergerson said.

Acknowledging this reality somewhat, several amendments have been put forward by other councilmembers that would slightly walk back the expectation around new sidewalks, instead shifting millions of dollars to sidewalk repair instead. A proposal by District 3 Councilmember Joy Hollingsworth would shift $15 million, and a proposal by Council President Sara Nelson would shift $20 million. But during a levy committee meeting last week, no councilmembers asked the SDOT staffers present in council chambers to weigh in on what funding levels would actually be achievable.

Spending funds that had been intended for new sidewalks on sidewalk repair is going to be more feasible for SDOT because sidewalk spot repair is more likely to be accomplished by in-house crews, whereas state law requires the City to contract out most new-build projects, even if they have relatively modest price tags. Sidewalk repair can also be bundled onto repaving projects along roadways that already have sidewalks, something that SDOT is doing with a project along 15th Avenue NW in Ballard. But the amendments may not go far enough. Hollingsworth’s amendment would reduce the goal to 440 new blocks by 2029, and Nelson’s to 400, but even those goals may be too ambitious for planned funding levels.

Bergerson told The Urbanist that going beyond 250 blocks within four years wasn’t something that the department is ready to sign onto, noting that 250 blocks in four years already represents a major accomplishment compared to recent history. “SDOT is committed to achieving this ambitious goal. Increasing the four-year goal beyond 250 blocks would require more changes and considerations as to how we select and construct sidewalks including staffing levels, contracting processes, and any effects increasing sidewalk delivery would have on other projects,” he said.

This may be hashed out by the time a final committee vote takes place on July 2, but if not, the city council may be making promises it cannot keep to city residents, who rightfully have been clamoring for more pedestrian infrastructure.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.