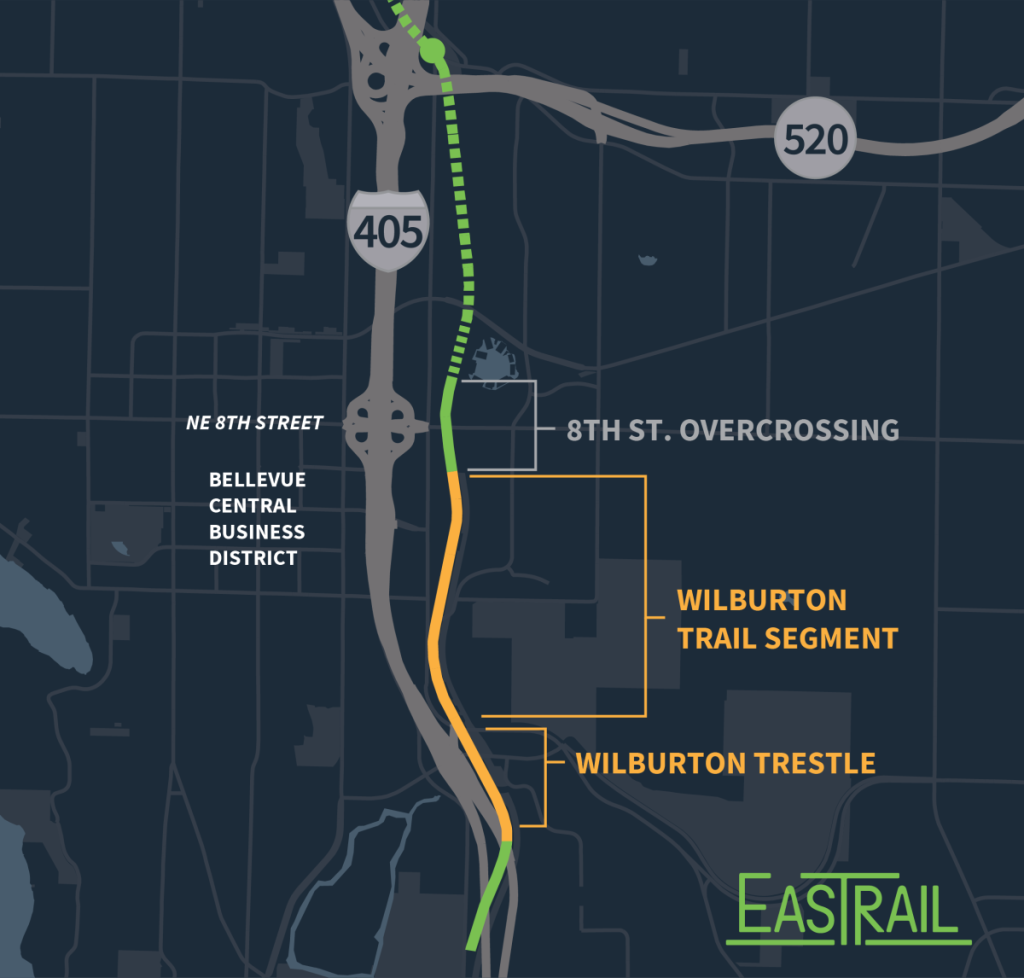

This weekend saw the grand opening of a new pedestrian and bike bridge over NE 8th Street immediately adjacent to Sound Transit’s Wilburton light rail station on the 2 Line. The $32 million bridge lets multimodal travelers bypass one of Bellevue’s most unpleasant and dangerous streets, and it unlocks the next short trail segment of the Eastrail, extending south to NE 4th Street. That stretch is the latest segment of the 42-mile Eastrail corridor planned between Renton and Snohomish County to open.

Made of pre-fabricated steel trusses, the exterior of the bridge is screened from the road by perforated aluminum panels. Ramps on either end add up to over double the length of the 200-foot bridge itself. Stairways connecting directly with the lower level of the light rail station on one side of NE 8th Street and the RapidRide B Line bus stop on the other were included as part of the bridge’s design, but were yet to open as of the ribbon-cutting.

Like much of Eastrail, the bridge will be owned and operated by King County Parks, and it was mostly funded via the 2015 county parks levy. However, the project also received $3 million in system access funding from Sound Transit, which opened the 2 Line a few feet away from the new bridge on April 27. So far, the line has seen ridership of around 4,000 trips per day, but much higher levels are expected once the line fully opens to Seattle, which was delayed by construction defects along I-90.

“By tying Eastrail and the Wilburton neighborhood to this new light rail station, the community now has an alternative to being stuck in traffic with all the negative consequences, whether it’s expensive gas or parking — you don’t need to drive,” Goran Sparrman, Sound Transit’s interim CEO told the crowd at Sunday’s ribbon cutting. “So the bottom line is this, we have to prioritize the local vision on the ground for projects like this to complement what my agency is doing and delivering on the very large scale capital projects, i.e. extending the Link light rail system, in order to really see the true vision that this region has articulated for a long time come to pass.”

Apart from providing an invaluable new connection, the construction of the NE 8th Street bridge has also been leveraged as an opportunity to highlight the history of Bellevue’s Japanese-American community, which has deep roots in Wilburton and the surrounding neighborhoods. Prior to World War II, people of Japanese descent composed 15% of Bellevue’s population and 90% of the city’s agricultural workforce. The Wilburton light rail station is located on top of the former home of the Bellevue Growers Association’s packing house, the only place on the Eastside where Japanese farmers were allowed to distribute produce.

In 1942, following the Pearl Harbor attacks and the declaration of war with Japan, President Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s signed Executive Order 9066, which relocated Bellevue’s entire Japanese population to an internment camp near Fresno, California. But anti-Japanese sentiment in Bellevue extended much further back in history, with Miller Freeman, the grandfather of Bellevue Square developer Kemper Freeman, founding Washington’s Anti-Japanese League in 1916. For decades, that history has mostly been swept under the rug in Bellevue, with the artwork being put in place here a big step toward shining a light on those past injustices.

King County Councilmember Claudia Balducci described the path to creating space at the new bridge for the history of Bellevue’s Japanese-American community to be told. “When we asked community members ‘what [are] the stories you want to tell,’ we heard three things consistently: tell the story of the contributions of the early residents of Bellevue who are Japanese-American citizens and immigrants who helped to create this city. Tell the story of incarceration due to racism, don’t let people forget that story. And then send the message, over and over, of never again — a resonant message,” Balducci said.

“I remember being in the room when we had the first visioning process with the artists where we asked them to celebrate and commemorate the history of our Japanese-Americans in Bellevue. And we wanted to celebrate the businesses, the farms, the families, the people who raise their families here. But we also felt it was very important to recognize the history in Bellevue,” Bellevue Mayor Lynne Robinson said. “And this that you see here today, are these artists’ stories, and it is their truth. And for the many Japanese-Americans who were forced to leave their farms, their businesses, their homes, and somehow when they came back, if they came back, they were asked to be silent. This is their truth.”

Taking the lead on creating the artwork for the bridge was the Bellevue Japanese American Legacy Project, which helped select Lauren Iida, Akiko Sogabe, and Lawrence Matsuda as the specific artists whose work has been featured in the “mixing zone” north of the bridge itself.

Eastrail is not slated to see another grand opening for a few years, as the final segments come together. Just a few weeks ago, King County celebrated the groundbreaking of the next major project that will bring the trail south, the Wilburton Trestle. That $37 million project, rehabilitating a railroad bridge from 1904, is set to open in 2026, and — in conjunction with a new bridge over I-405 being built by the Washington State Department of Transportation (WSDOT) — will get Eastrail tantalizingly close to completion. In the meantime, the new bridge will be a godsend for anyone traveling by bike or foot in Bellevue trying to avoid NE 8th Street.

In the coming days, the U.S. Department of Transportation will announce whether King County has been awarded $25 million for a planned bridge over Interstate 90 that will fill in the final gap. (Update: the $25 million was secured, US Senator Patty Murray announced Monday.) Even with that award, the trail is not expected to be open for use until at least 2030. But segment by segment, the pieces are falling into place on what will be one of the best intercity trail connections in Washington State when it’s finally complete.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.