Responding to the most common arguments against using land use policy to fight climate change

In part 1 of this series, I talked about the many ways that smarter land use patterns can reduce greenhouse gas emissions. So why isn’t land use a more prominent part of climate advocacy in the US today? To answer that question, I will unpack some of the arguments against a land use strategy, and identify where those arguments take a wrong turn.

Argument #1: Electrification Makes Land Use Changes Irrelevant

In recent years solar panels, wind turbines, electric vehicles, and electric heat pumps are rapidly falling in cost and increasing in market share. This powerful trend towards renewables and electrification is due in large part to policy changes that have been a big focus of climate advocates over the last decade. We should all be thrilled this is happening and thank the hard work of advocates and courageous elected officials that enacted the policies that are accelerating this transition.

You may have noticed, in the previous post, that the benefits of more compact land use patterns are primarily about reducing energy consumption, not about changing the source of that energy. People often ask me: can’t we just electrify our vehicles and buildings and build more clean energy generation, and then it won’t matter how much we drive or how energy-efficient our buildings are? And then we won’t need to sequester carbon either, right?

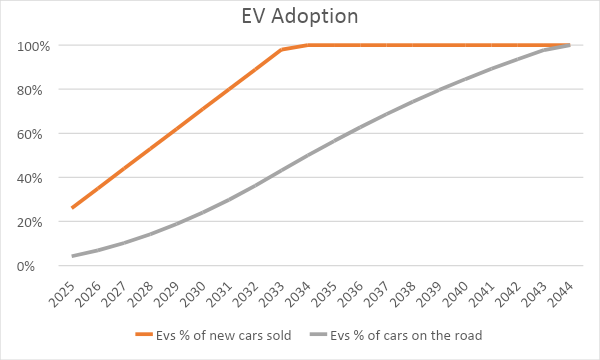

Ultimately, we do need to electrify everything and complete the transition of our electricity generation to renewable power and we need to do it as fast as possible. But even the fastest electrification and clean energy transitions will take time. In 2019, Washington State committed to require that all new cars sold will be electric by 2035. That’s an aggressive timeline, but that’s just new cars sold. It will take many more years for new cars to replace all of the old fossil fuel burning cars. The figure below gives us an optimistic example of what this could look like based on the state’s ambitious targets and some simple assumptions about new cars sold per year. Here you can see that we still have fossil fuel burning cars until 2045.

Despite starting with one of the lowest emissions electrical grids in the country, the most recent inventory taken in 2020 showed our electrical grid was still generating 16.5 million metric tons of carbon. Even the state’s ambitious requirements under the Clean Energy Transformation Act don’t achieve 100% clean energy until 2045. The fewer miles driven by our new EVs the easier it will be to meet that 2045 goal.

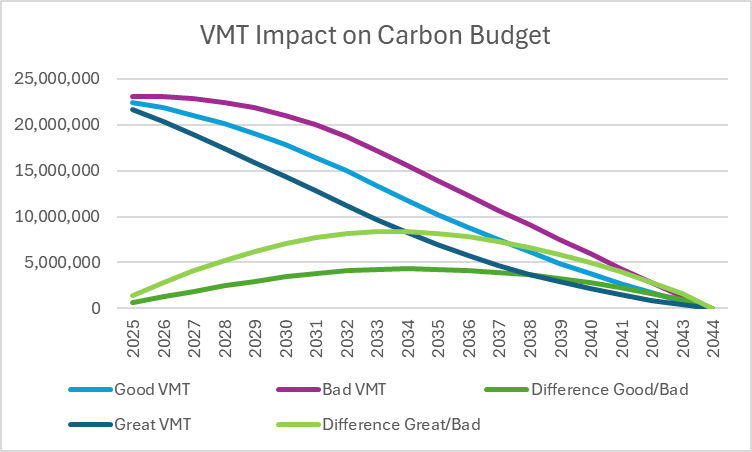

Even if we do get to 100% clean energy and 100% electric vehicles by 2045, it matters how much we emit along the way. Vehicles miles traveled or VMT is the metric used to evaluate the total amount of miles traveled by motor vehicles in a region over a time period. Below is how the transition to electric vehicles and clean energy plays out in emissions under a Bad VMT Trend, a Good VMT Trend, and a Great VMT Trend.

The Bad Trend assumes that VMT per capita increases by 1.8% per year, as it did across the US from 1980-2005. The Good Trend assumes that VMT per capita declines by about 1% per year, as it has for much of the last two decades in Washington State. The Great Trend assumes a more dramatic reduction of 4.5% per year, that we have seen over the last two decades in climate leaders like Paris. As you can see, even though in both scenarios driving emissions (tailpipe, fuel production, and transmission for gas and electric vehicles) go to zero in 2045, the difference in emissions over the next 20 years is significant. In this hypothetical optimistic EV transition scenario, the modest difference between the good and bad trends results is about 56 million metric tons of carbon. The difference between the great and bad trends is about twice as big.

This is just an illustration of the relationship between VMT, EV adoption and overall emissions. There are lots of folks out there doing more rigorous calculations along these lines. Rocky Mountain Institute’s report on Why Land Use Reform Should Be a Priority Climate Lever for America is a great example. Their report looks more narrowly at the benefits of just directing more growth to existing low-carbon neighborhoods, and they found the potential to reduce emissions by 70 million metric tons per year across the US.

About half of those reductions would be from reduced driving while the other half would come from the other types of reductions I described in my previous post, as well as emissions from EV manufacturing. That ratio would indicate that the total emissions reductions from land use changes should be about twice the reductions just from changes in VMT.

Those are significant emissions savings, roughly equivalent to all of 2019 emissions in the good case and twice that year’s emissions in the great case. But the other factor to consider is: how confident are we that we will achieve our EV and clean energy timelines? Despite the landmark legislation the state has passed, these goals will still be hard fought. Permitting, transmission lines, electrical grid improvements, charging infrastructure, access to rare raw materials, supply chain hiccups, rising vehicle costs relative to middle class spending power, and consumer resistance are all major challenges ahead. If the transition to EVs and clean energy takes long, the savings from annual reductions in VMT start to balloon, making it an important backup strategy.

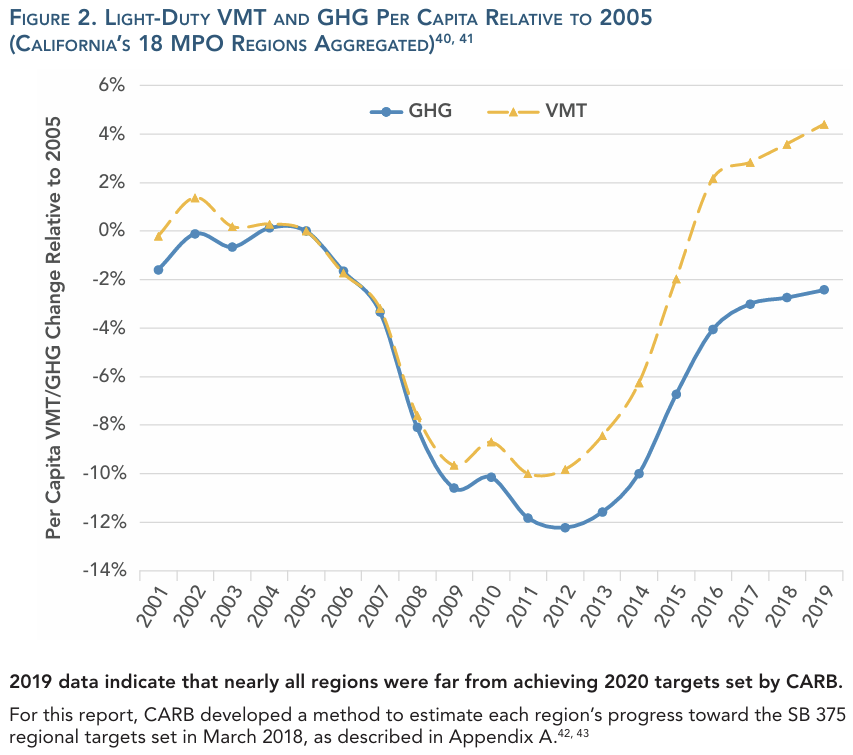

California presents a warning for what happens when land use and other VMT strategies are neglected. Despite California’s early lead in building clean energy, requiring more fuel-efficient cars, low-carbon fuels, and the transition to electric cars, greenhouse gas emissions from transportation have stayed stubbornly high. The reason: Californians keep driving more.

Last but not least, in addition to worrying about the carbon emitted before the transition to electric vehicles and clean energy is complete, we also need to worry about our total capacity for renewable energy production. The less we drive in our fully electric future, the fewer EVs and the less renewable energy we will need. This is important because it is going to be hard to build all the renewable energy and batteries and cars we need. Even though renewables and batteries are way better for people and the planet than fossil fuels, mining of batteries and siting of renewable energy projects still have significant environmental impacts.

We also do not yet have the technology to cost-effectively eliminate emissions from the manufacturing of steel, concrete, and many other materials. The fewer cars, roads, parking lots, etc that we need to build, the more time we have to figure out these aspects of industrial decarbonization.

Argument #2: Land Use Changes Are Unpopular

There is a fear that land use changes are unpopular and that their unpopularity will contaminate the broader climate movement. I think this perspective comes from two assumptions, one mistaken and one outdated.

This first false assumption is that land use changes are about forcing people into a horrible, un-American life that they will hate. Addressing this assumption takes some context. There is an old current in the environmental movement that saving the planet is about personal self-sacrifice; if you care about the environment or the climate you should eat less meat, stop flying in airplanes, put on a sweater instead of turning up the heat, wake up earlier to take the bus to work, etc.

These are all noble sacrifices for individuals to make if they can, but policies that are framed in terms of taking away things that many people like (meat, flying, being warm, sleeping more, etc) are very unpopular and they let powerful corporations and government agencies off the hook. You’ve probably heard the fossil fuel lobby say things like, radical climate activists are trying to take away your hamburgers or ban cars.

Most climate advocates have, I think rightfully, moved away from anything that is focused on this type of personal sacrifice. Land use changes mistakenly get lumped in with this strain of environmentalism. People think that we are going to have to force people to live in places they don’t want to live and that will be unpopular.

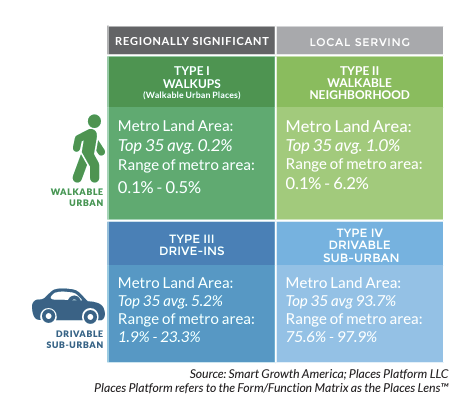

The reality is the opposite. We are currently forcing many Americans to live in auto-dependent, low-density places where they don’t want to live. Many of these folks would choose to live in walkable, urban neighborhoods if they could. This dynamic is most easily seen in the long history of surveys that ask Americans if they would rather live in a smaller home that is in a walkable neighborhood close to amenities and jobs or a larger home where you have to drive to get to those same things. While it’s true that a majority of Americans pick the bigger home, a large minority, 42% in Pew Research’s 2023 survey, choose the smaller home near amenities. The problem is that, today, very little of the US fits the preferences of that 42%.

In Smart Growth America’s 2023 Foot Traffic Ahead report, only 1.2% of neighborhoods in the 35 largest metropolitan areas met these criteria. This huge disparity in supply and demand has also contributed to big price premiums for more compact walkable neighborhoods. Many millions of Americans want to choose the smaller home that is close to things, but single-family zoning, large lot-size requirements, and a thicket of other regulations severely limit our ability to build new walkable neighborhoods and also make it hard to add homes in these existing neighborhoods. To get more climate-friendly land use patterns, we don’t need to force people against their will: we just need to remove those limitations so the 40% of Americans who are locked out of these neighborhoods can live where they want.

That brings us to the second assumption, which is the outdated notion that removing the limitations described above is unpopular, not for the people moving into the new homes, but for the neighbors. If you’ve been to a community meeting about an upzone or a new building proposed for your neighborhood, you’ve probably seen the opponents show up to rail against these changes. That still happens, but increasingly the broader public wants to see change. These politics are moving fast, and Seattle and Washington State are a great example.

In 2016, when then Seattle Mayor Ed Murray proposed allowing triplexes on every single-family lot, the backlash was fierce and immediate. As a result, the idea was quickly cut from the 65 affordable housing strategies in his Housing Affordability Livability Agenda. But seven years later, the state legislature passed HB 1110 by wide margins, which will require that local jurisdictions allow more housing types in nearly every urban and suburban neighborhood in the state.

In 2023, suburban city council races saw a string of victories for candidates that supported more housing and more walkable neighborhoods. New polling by the Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce shows that 69% of Seattleites now support more housing types in their neighborhoods.

By embracing these policy changes, climate advocates have an opportunity to not just do something popular, but to make new allies from those who have been leading this political transformation. The details of implementation are important. How these changes happen, how they address concerns about displacement, tree canopy, urban design, and the capacity of local infrastructure and services, will affect the popularity of these policies. But we have come a long way from 2016 and the political assumptions need to catch up to the new reality.

Can Land Use Changes Make Other Climate Strategies More Popular?

Letting people live in walkable neighborhoods close to amenities and jobs is not just popular, it also has the potential to make other climate policies more popular. This year big money reactionary forces are launching a campaign to repeal the Climate Commitment Act through I-2117. Their message has been focused on high gas prices. Are communities that are more dependent on driving to get to jobs, school, the grocery store, etc., more responsive to this message? Futurewise has been conducting original research to try to understand this relationship.

I-2117 is similar (but in reverse) to initiatives that were on the ballot in 2016 (I-732) and 2018 (I-1631). Both initiatives would have put a price on carbon with I-732 reducing other taxes and 2018 investing the tax revenue in climate justice strategies. Both initiatives failed, but we can learn something from those votes.

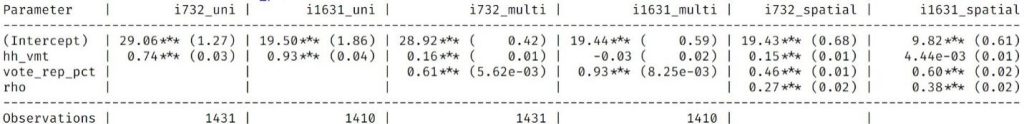

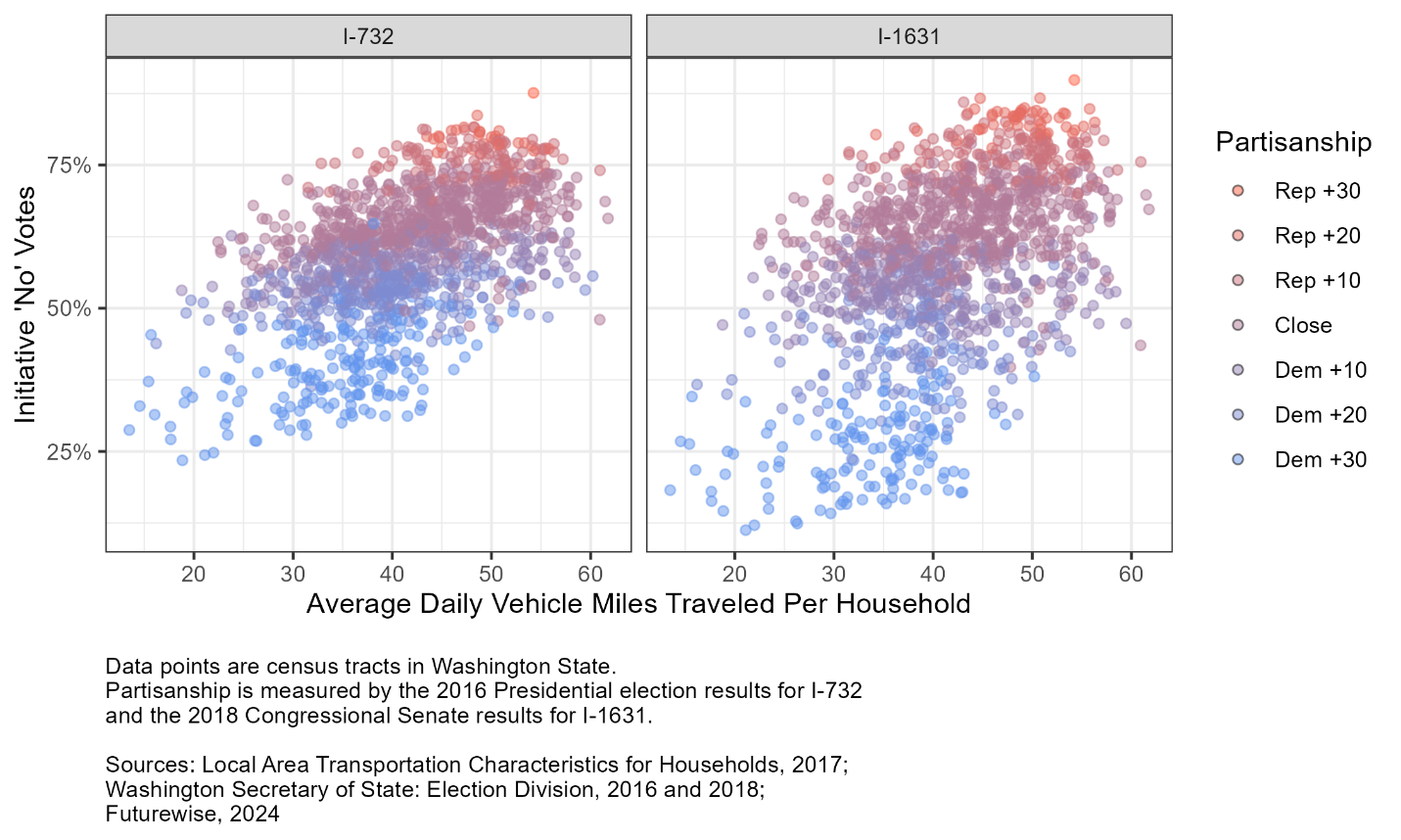

The amount households drive varies a lot by census tract. At one end of the spectrum, the average household only drives about 10 miles per day. At the other end, the average household has to drive 60 miles per day. To understand the relationship between these travel patterns and voting behavior, we can compare the votes, by precinct, for both I-732 and I-1631 to these average daily travel distances for the corresponding census tract. We looked at this relationship on its own and when controlling for partisanship (using 2016 Presidential vote share) because party affiliation is also correlated with average neighborhood travel distances.

On the first pass, without controlling for partisanship, there was a clear correlation between driving and voting patterns for both initiatives. For I-732, for every additional mile that the average household had to drive each day in a given census tract, that neighborhood had another 0.74% of the vote against I-732, that is to say, another 0.74% of the vote against taxing greenhouse gas emissions.

For I-1632, that initial influence on voting patterns was even higher, with an added 0.93% for the “no” vote for every mile driven. Interestingly, the relationship with partisanship was very different between the two initiatives. For I-732, even when adjusting for partisanship, each mile still increased the percentage vote against the initiative by 0.15% and was very statistically significant. For I-1632, in contrast, once partisanship was included, the relationship to VMT went essentially to zero and was no longer significant.

What conclusion can we draw from this preliminary analysis? At least in some cases (I-732), people who live in the more walkable, compact neighborhoods with less driving are more likely to vote for climate policies, regardless of partisanship. Creating more neighborhoods where people are not forced to drive could help build more support for climate policies. However, this relationship did not hold for I-1631. Why the difference?

One possible explanation relates to the specific policy design and politics of the two initiatives. I-732 proposed a market-based system with a focus on reducing other taxes. While Democratic voters are more generally supportive of climate initiatives, this structure may have appealed more to Republicans and less to Democrats. This may have led voters to focus more on the personal pocketbook impacts and less on the partisan associations of climate change. I-1631 was designed with an environmental justice focus on increasing government investment to address the needs of frontline communities from both the initiative’s pricing policy and climate change itself. This may have earned support from traditional Democratic constituencies, even in neighborhoods that are very dependent on driving, while turning off more Republicans.

Overall, this analysis suggests that if we build more compact, walkable neighborhoods, more places that require less driving, then we have the potential to cultivate more voters that are supportive of a wide range of policies to address climate change. This isn’t a guaranteed political transformation, but it is one more tool in our toolbox to tilt the playing field towards a more rapid, just transition to address the climate crisis.

Argument #3: Land Use Policy Changes Are Ineffective or Too Slow

We have already established that changes in land use patterns can have a significant impact on emissions even if we are also successfully electrifying our cars and buildings. We have also established that allowing more homes in low-carbon neighborhoods can be popular. But can we actually change our land use patterns? Have we ever done that successfully before? And can we do it fast enough? These are the questions and skepticism that I get most frequently, particularly the aspect related to speed. My first reaction when I get these questions is just to shout “Yes, yes, and YES!” But I’ve learned that’s not a very productive response.

Instead, I want to take some time to walk through where I think these concerns come from, acknowledge some of the difficulties, but then chart out how it can be done and why there are very good reasons to think this is in fact one of the best policy areas right now for climate advocates, elected officials, and funders to invest their time, political capital, and money. That will be the subject of the third post in the series.

Alex Brennan

Alex Brennan is the executive director at Futurewise, a nonprofit that works to create more livable communities. He is a resident and renter in the 43rd Legislative District. He holds a Masters of City Planning from the University of California, Berkeley.