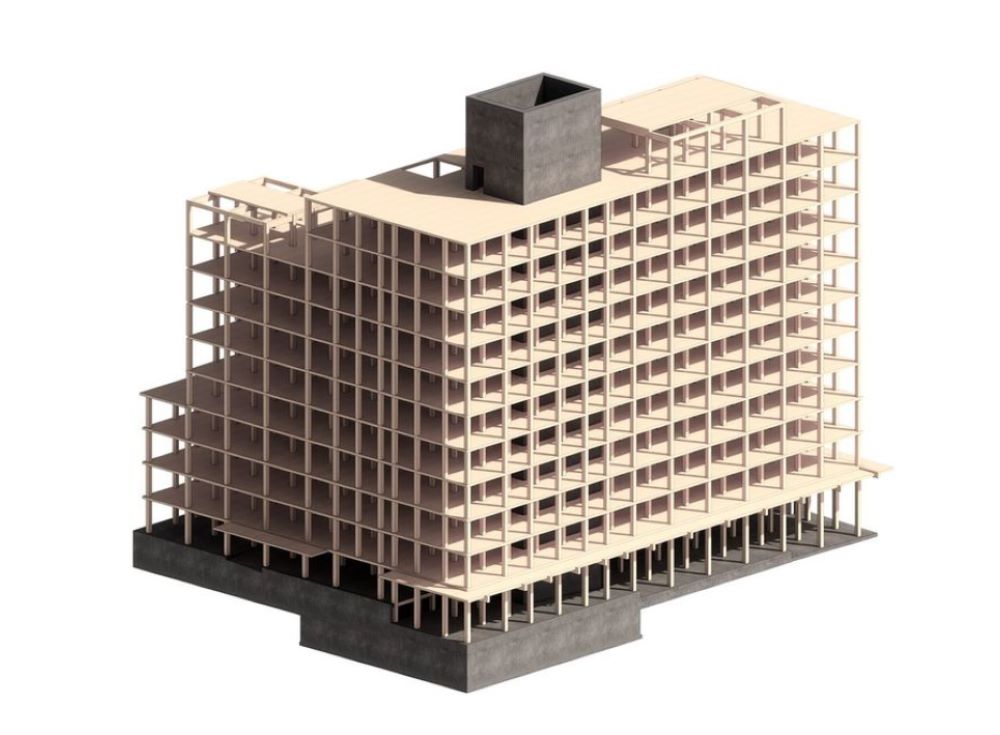

In April, the Low Income Housing Institute (LIHI) announced plans – in partnership with Sound Transit and the Seattle Office of Housing – to build a 12-story mass timber affordable housing complex near U District Station. Though it’s still in the early design stages, the early plan envisions 160 homes serving families and individuals earning between 30% and 80% of area median income (AMI). At 12 stories, it would be the tallest mass timber building in Seattle.

“LIHI is excited about the prospect of working with mass timber framing, a more environmentally sustainable way of building,” said LIHI director Sharon Lee. “We are studying the costs and weighing the advantages of mass timber as we work to balance innovation in design with cost effectiveness.”

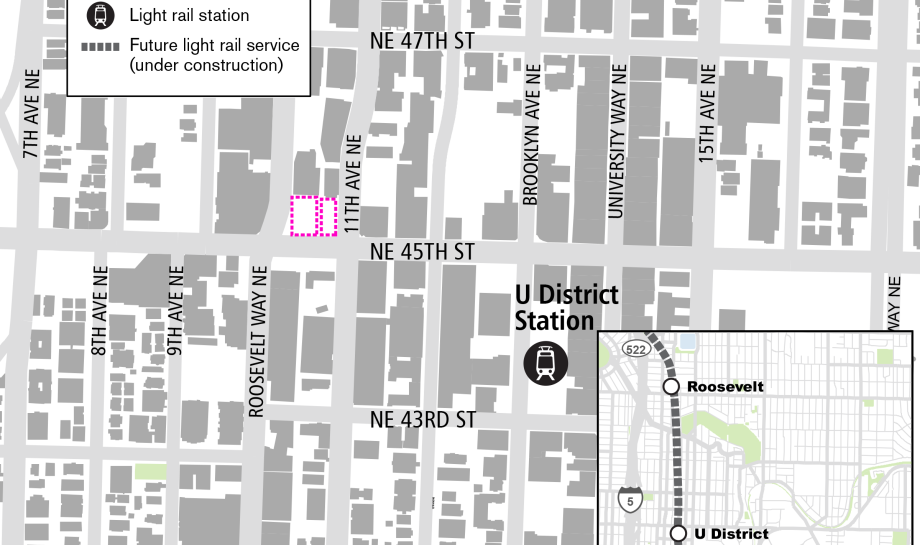

The project will be built at NE 45th Street and Roosevelt Way, two blocks from the Link light rail station, on land that Sound Transit owns but has designated as surplus. The property, which was used by Sound Transit for construction offices and parking during construction of U District Station, was made available to LIHI through a bidding process as part of the transit agency’s mandate to make at least 80% of its surplus property available for affordable housing at low or no cost.

Sound Transit and the Seattle Office of Housing selected LIHI’s plan after a competitive process in 2023. The proposed project, which is being designed by local architecture firm Hewitt and the Oakland-based firm Pyatok, will offer a range of affordable housing options, including units for people earning 30%, 50% and 80% of AMI. One third of the units will be two- and three-bedroom apartments suitable for families. LIHI hopes to start construction in 2026.

The Office of Housing has committed $15 million to the project. LIHI says the remainder of costs will be covered by private debt, tax-exempt bonds, low-income housing tax credits, and charitable grants.

“The housing will prioritize people in the U District and other neighborhoods who are experiencing unaffordable rents and displacement,” Lee said in a press release announcing the project.

The site is currently home to Rosie’s Tiny Home Village, a collection of 36 small, furnished homes managed by the King County Regional Homelessness Authority and operated by LIHI. Since 2021, Sound Transit has made the property available rent-free to establish the tiny house village, which can serve up to 65 people who would otherwise be without shelter. Lee said LIHI has begun the process of finding a new site for Rosie’s Village, which is one of six LIHI sites in the University District. “We wish to thank the U District community for its wonderful support for Rosie’s Village,” Lee said.

The 45th and Roosevelt project will also serve as a new permanent home for the neighborhood’s Urban Rest Stop, which closed in 2020 after the lease expired. Each Urban Rest Stop (with locations in downtown and Ballard as well) offers laundry, showers, and other hygiene services to those who are homeless.

“For years, the community has identified affordable housing and public restrooms as top priorities for the neighborhood,” said Don Blakeney, Executive Director of The U District Partnership. “This project will deliver both, in addition to an Urban Rest Stop, which will meet many of the needs of our unhoused population in northeast Seattle.”

Sound Transit’s mandate to use surplus land for affordable housing

Following a major rezone of the U District in 2017, the neighborhood has rapidly grown and increased housing density. Tim Bates, a project manager for Sound Transit, said that the relatively small property allows Sound Transit to add needed affordable housing to its transit-oriented development mix in a neighborhood with 40,000 residents.

“We conducted community engagement starting in 2021,” said Bates. “In that community, we saw strong support for the site to become affordable housing.”

Because the relatively small, 18,000-square-foot property was bisected by an alleyway, Sound Transit sought and received conditional approval from the Seattle City Council in 2023 to remove the alley. LIHI and Sound Transit are working with University Heights Center to conduct public outreach on vacating the alley prior to construction.

Though Sound Transit’s surplus property is a small fraction of the land surrounding each Link station, Bates says the agency’s mandate to develop the majority of it for affordable housing makes a significant impact. “We’re seeing that increased access to regional transit – especially high capacity stuff – can boost people’s desire to live and work near those stations,” Bates said. “And that can increase land values. Part of our goal is to ensure that there remain long-term affordable units near our stations so that access can be provided to a wider set of community, not just one at the higher end of the income spectrum.”

A 2015 state law requiring 80% of Sound Transit’s surplus land be made available to create housing for people making 80% of AMI or lower, prompted the agency to create a transit-oriented development (TOD) program that has created more than 2,600 affordable homes, with many projects receiving the land for free.

A project similar to the 45th and Roosevelt development is Cedar Crossing, a 254-unit affordable housing building near Roosevelt Station, created in partnership with Bellwether Housing and Mercy Housing NW, which opened in 2022. Other affordable TOD projects in the pipeline include a six-acre parcel near the upcoming Federal Way Station, two apartment buildings with 167 affordable units near the future Lynnwood City Center Station, developed by Housing Hope, and a 130-unit affordable housing apartment building that Mercy Housing NW will develop near Angle Lake Station.

Mara D’Angelo, deputy director of Sound Transit’s TOD program, says the Sound Transit Board is moving forward on surplus property at the future Marymoor Park station in Redmond, noting “We just went to our board around the Marymoor TOD site in Redmond to declare that property surplus so that we could start the process of planning community engagement around that site,” D’Angelo said. “We have things going on in all directions.”

Mass timber taking off in Seattle

According to Cody Lodi, a design principal at Weber Thompson and co-chair of AIA Seattle’s Mass Timber Committee, mass timber projects can be between 25% and 40% more carbon efficient on average than conventional concrete buildings – though each project can vary immensely.

Alex Zink, who’s also a co-chair of the Mass Timber Committee, and an architect at Miller Hull, notes that while each building is different, using mass timber can result in a much more climate-friendly development, especially when architects are careful in making choices that can determine a project’s overall climate impact. “Concrete is really bad for carbon in the environment,” Zink said. “So, if you’ve got a really big underground parking garage, that’s a ton of concrete. If you’re not building that, regardless of what’s above ground, it helps save on carbon.”

The Pacific Northwest is a hotspot for mass timber development, but Seattle has been eclipsed in recent years by projects in Vancouver, British Columbia and Portland. Still, Zink says Seattle is quickly catching up.

Zink and Lodi declined to comment on the 45th and Roosevelt project because of their role within AIA Seattle and their interest in not commenting on a work in progress by other architecture firms.

But in general, they say many mass timber projects are coming online in Seattle. Most technologies in mass timber aren’t particularly new, but offer a fire-resistant, climate-friendly alternative to concrete or steel. The majority of projects incorporate cross-laminated timber (CLT), nail-laminated timber (NLT), dowel-laminated timber (DLT), glue-laminated timber (glulam or GLT), or some types of structural composite lumber (SCL).

“Most [mass timber] is actually not really new technology,” Lodi said. “Most wooden buildings that you’ve seen in the last 20 years. . . use glue laminated conventional lumber that’s glued and pressed into larger beams.”

While mass timber can be more expensive than a conventional building, savings can be found in labor and scheduling costs, Zink said, because many building components are pre-manufactured in a factory, and quickly assembled on site. “The labor crews are much smaller,” he noted. “It can be like three to five times smaller, as opposed to a concrete building.”

One notable project that Lodi worked on in Seattle that opened recently is Northlake Commons in Wallingford, a five-story office building incorporating a Dunn Lumber retail warehouse on the first floor. Changes to Seattle’s building code in 2021 allow for more exposure of timber beams and panels – creating a more natural, open feel.

It also allows for taller buildings employing mass timber Lodi pointed to the new Heartwood Workforce Housing project on Capitol Hill, an 8-story 126-unit affordable housing project developed by Community Roots Housing as an example of the new building code driving taller buildings incorporating mass timber. Statewide code changes enacted in 2018 allow mass timber buildings as high as 18 stories; when using exposed wood, however, the limit is 12 stories.

“Some building code changes adopted in the 2021 building cycle are allowing for more exposure of the mass timber and taller buildings,” Lodi said. “That’s what’s going to lead to more of these 12-story timber buildings, which can benefit by showing the wood off and its natural warmth. Heartwood was one of the first to make use of some of these new code options.”

Heartwood is not far from the Bullitt Center, Seattle’s first tall office building utilizing mass timber construction, which last year celebrated its tenth anniversary.

The new code allowing for more exposed wood (which formerly had to be covered with gypsum or other materials to meet fire codes) also helps reduce costs and make it a more attractive option. Zink noted that architects, as they design more and more mass timber buildings, are learning ways to use timber more efficiently in their designs.

“The cost is slightly higher, on average, but there are workarounds,” Zink said. “Wood is a material that’s expensive. You want to limit the amount of what you use. So particularly in your floor thickness, if you can make your floor as thin as possible but that still works structurally, then you’re saving money.”

One added benefit of mass timber is that it’s a much more emotionally resonant material. Lodi notes that whether it’s in an affordable apartment or an office space, people are generally happier in those spaces – when they incorporate elements from the natural world, what Lodi refers to as the biophilic response whether it’s wood, stone, or natural light

“Biophilia is basically human beings’ innate connection to nature,” Lodi said. “Several studies have shown that our internal response to those types of spaces reduces anxiety and stress. It has a calming effect.

“When you’re thinking about an affordable housing project, you get those benefits from the space in which you live,” he said. “You don’t get that from looking at a concrete ceiling.”

Andrew Engelson

Andrew Engelson is an award-winning freelance journalist and editor with over 20 years of experience. Most recently serving as News Director/Deputy Assistant at the South Seattle Emerald, Andrew was also the founder and editor of Cascadia Magazine. His journalism, essays, and writing have appeared in the South Seattle Emerald, The Stranger, Crosscut, Real Change, Seattle Weekly, the Seattle Post-Intelligencer, the Seattle Times, Washington Trails, and many other publications. He’s passionate about narrative journalism on a range of topics, including the environment, climate change, social justice, arts, culture, and science. He’s the winner of several first place awards from the Western Washington Chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists.