King County Metro is adding hydrogen-powered buses to its fleet as part of a pilot testing program. It’s a sudden announcement for an agency that had been pinning its fleet electrification strategy on battery-electric buses, barely contemplating hydrogen buses previously.

“While still delivering everyday, high-quality service to our riders, we’re also leading the way to a zero-emissions future,” Michelle Allison, Metro’s General Manager, said in a statement on Wednesday. “We’re partnering with public entities across our region, encouraging private contractors to develop technologies, and learning and sharing each step of the way.”

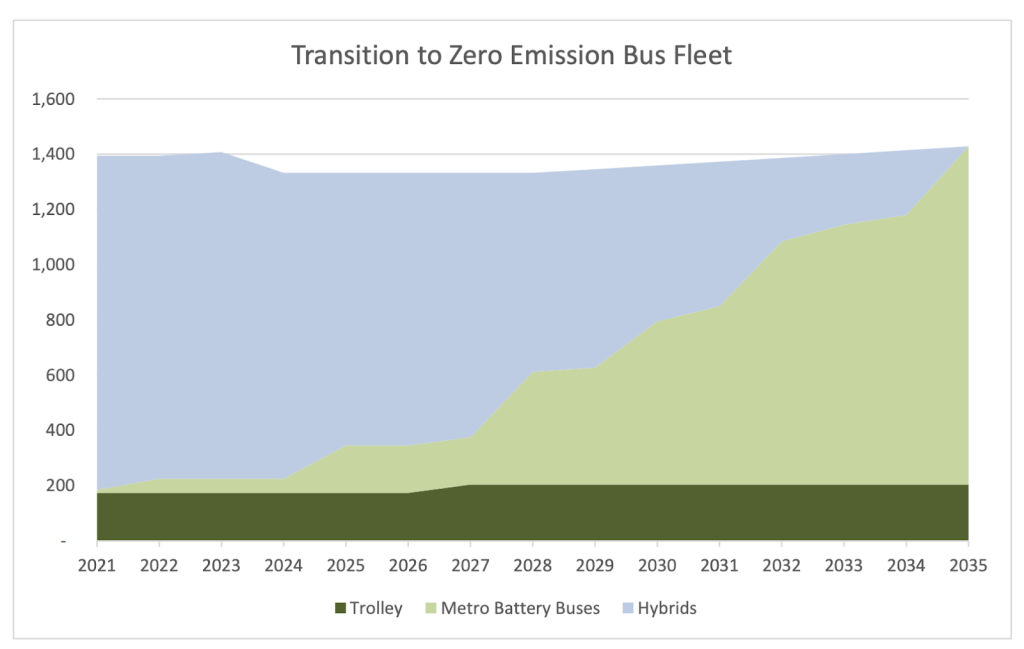

In 2017, Metro set a goal to electrify its bus fleet by 2035, but seven years later only about 50 of its 1,200 non-trolley buses are fully electric, which is just over 4%. The gradual rate of electrification stems partly from battery bus technology advancing slower than hoped.

This news has big energy! 🍃💧 Metro will explore piloting up to four hydrogen fuel cell buses as early as 2026. Read more: https://t.co/51xTu06hIl #ZeroEmissions #PublicTransit pic.twitter.com/Wui1LGBiEh

— King County Metro 🚏 (@KingCountyMetro) June 12, 2024

Metro joins four other Puget Sound transit agencies in evaluating hydrogen fuel cell buses. Community Transit already acquired one 40-foot fuel cell bus that is set to go into pilot testing this fall, and Intercity Transit, Pierce Transit, and Kitsap Transit appear poised to follow suit in the coming years with their own demonstration projects.

One reason why Metro is pursuing fuel cell buses boils down to operational needs and constraints. “While battery-electric buses have an expected range of 140 miles for a 60-foot bus and 220 miles for a 40-foot bus, Metro and other transit agencies have experienced range limitations and variability, especially in cold weather,” the agency wrote in a blog post. “Hydrogen fuel cell buses have the potential to travel up to 300 miles and their extended range has particular promise on all-day, frequent routes.”

By 2026, Metro hopes to begin piloting four fuel cell buses as part of an 18-month testing and evaluation period. The agency intends to understand how fuel cell buses operate in different local terrain and weather conditions, and develop related operating and training protocols. Consequently, the buses won’t operate in revenue service until that process has been completed and the vehicles are deemed ready for riders.

Before any of that can happen, Metro needs formal approval from the King County Council. The agency plans to bring forward a budget request this year to authorize vehicle procurement.

Which manufacturer will produce the fuel cell buses or even the specifics of sizing remains unanswered, but the agency has said that procurement costs are slightly higher than for battery-electric buses. Costs for a typical 40-foot battery-electric bus run around $1.2 million while a 60-foot battery-electric bus is around $1.8 million, according to the agency.

Up until last week, Metro had been telegraphing that battery-electric buses would be the agency’s primary fleet electrification solution, with electric trolleybuses taking a backseat. The agency’s latest electrification transition plan from 2022 had clearly outlined a framework to reach a zero-emissions fleet by 2035 using only battery-electric and electric trolleybus technologies. The fact that Metro is now abruptly considering another zero-emissions technology could represent a shift in strategy, and perhaps some second thoughts about battery-electric buses.

A report issued a day before Metro’s public announcement of the hydrogen fuel cell buses offers some clues beyond what the agency has publicly said. In the 43-page report, the King County Auditor’s Office raised numerous issues and concerns over Metro’s plan to rely so heavily on battery-electric buses.

“Metro has devoted substantial resources to organizing its department to transition to a zero-emission bus fleet by 2035, through improving the planning and collaboration efforts needed for this goal,” the report said. “It also faces significant risks that may impede reaching the goal, including the loss of bus manufacturers, technology limitations, sufficient electricity supply in the future, and lagging battery-electric bus performance.”

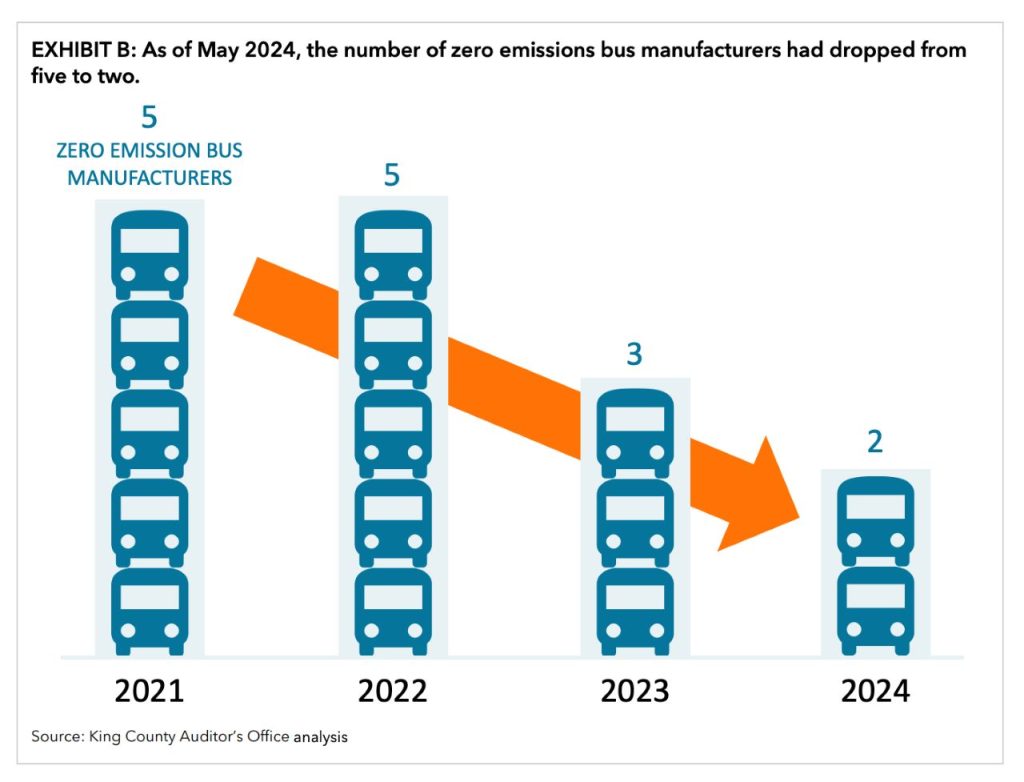

The auditor’s report was candid about the challenges Metro faces if it were to rely almost entirely on procurement of battery-electric buses.

Manufacturers have been leaving the North American market, declining from five in 2021 to just two this year: New Flyer and Gillig. That has put pressure on the two remaining manufacturers to produce battery-electric buses, as demand for them from transit agencies across the continent has soared. Consequently, this perfect storm could constrain Metro’s ability to maintain a necessary fleet size for operations as the agency transitions to a zero-emissions fleet.

Furthermore, the auditor flagged the reliability issues Metro has encountered with battery-electric buses in the field. “In March 2024, Metro reported that roughly 50% of the New Flyer battery-electric buses were out of service on any given day,” the report said.

New Flyer constitutes almost all of Metro’s current battery-electric bus fleet, and given its status as one of the only two remaining battery-electric bus manufacturers in the North American market, totally phasing out New Flyer may not be a feasible option.

Another major obstacle to fleet conversion that the auditor underscored is enhanced electrical systems.

“Metro estimates it will need additional electric utility infrastructure to provide sufficient electricity at three bus bases — and the long lead times needed by utility companies to build infrastructure create risk of not achieving sufficient electricity for a full transition,” the report said. “New substations take six to eight years to reach completion, in part because of the complexity of projects and permitting requirements. Metro plans to begin operations using its battery-electric buses at East Base in 2030, meaning the process for additional utility infrastructure would need to begin in 2024.”

However, in just the case of East Base, the auditor reported that an agreement with Puget Sound Energy has yet to transpire for needed power, so a 2030 opening as a battery-electric base could already be tenuous.

A myriad of other problems are further outlined in the auditor’s report, but some of the more eyebrow-raising ones are that current battery-electric bus technology is insufficient for use on workhorse routes — like RapidRide lines — and that the buses have significantly lower passenger capacity than hybrid-diesel buses.

In terms of the fuel cell buses themselves, details remain thin at this point. Metro’s blog post from last week offered little insight into the vehicles. The Urbanist sought information on topics such as make and model, how they would be funded, where they might be based from, if this foreshadows a major shift in the agency’s recently formulated electrification plan, and whether an updated transition plan would be pursued. Metro communications staff mostly declined, saying it was “just too early in the process to provide an answer.”

Use of hydrogen as a zero-emissions option does present an environmental challenge for Metro due to current production methods. Most readily available hydrogen fuel sources involve relatively dirty production methods relying on fracked gas, generating significant greenhouse gas emissions in the process. Transportation of hydrogen also adds to environmental impacts since the fuel is usually trucked by non-zero-emissions vehicles. However, there are various projects underway — including in the Pacific Northwest — to bring production facilities online that produce less greenhouse gas-intensive or even green hydrogen fuels, which Metro is hoping to see come to fruition.

As for hydrogen used in buses themselves, there are no direct negative environmental impacts when the vehicles are in service. That’s because fuel cells combine oxygen from the air with compressed hydrogen gas, resulting in three primary outputs: electricity, heat, and water vapor (H2O). That electricity is used to propel the bus and run its other mechanical and electrical systems. Heat can also be used and directed to warm areas inside buses.

While Metro may wind up making fuel cell buses a bigger part of the agency’s fleet than originally intended, the agency isn’t giving up on battery-electric buses yet. Metro is still moving forward with a fresh procurement for 89 battery-electric buses from Gillig, set to start arriving by 2026. Advances in charging equipment — such as en route wireless induction and overhead chargers — may also hold promise in extending the operational range of battery-electric buses, addressing some of the challenges that Metro faces. For now though, the agency’s zero-emissions transition plan appears in flux as it grapples with the limitations of technology.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.