A neighborhood street alongside a popular natural beach in West Seattle was transformed early this month with concrete barriers that send a clear message about who the City is prioritizing with the design of the street. The changes along Beach Drive SW on the south end of Alki Point, represent the latest attempt by the Seattle Department of Transportation (SDOT) to provide more space for walking, biking, and rolling, after a pandemic pilot program proved popular.

Efforts to improve safety on Beach Drive faced considerable opposition over parking removal, with an added twist provided by the area’s context as a regional draw for beachgoers. Whale watching and seal sitter groups have waded into the debate, arguing the parking is essential to their operations.

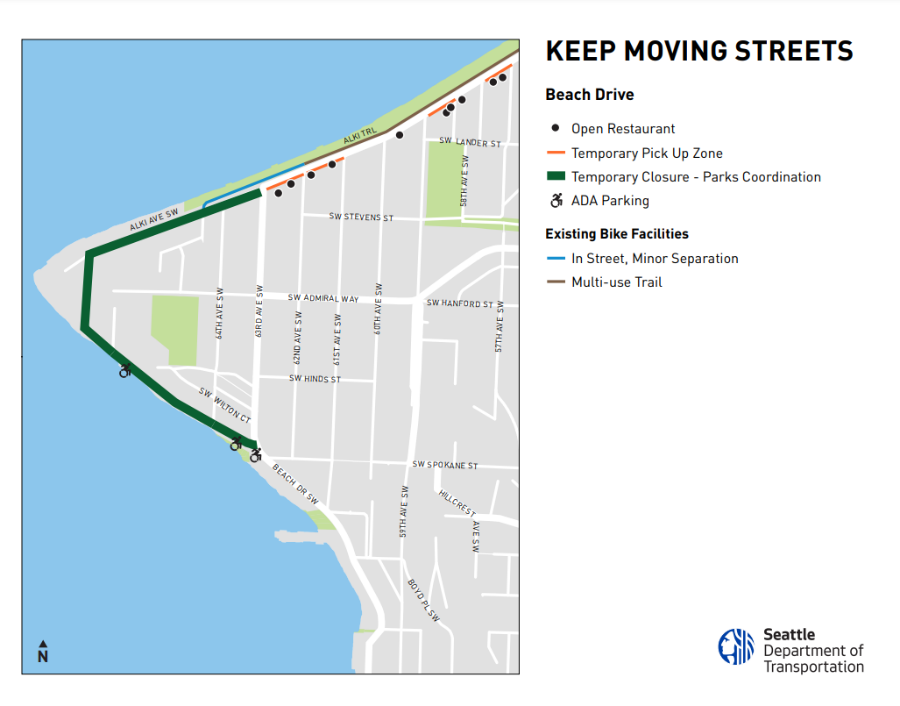

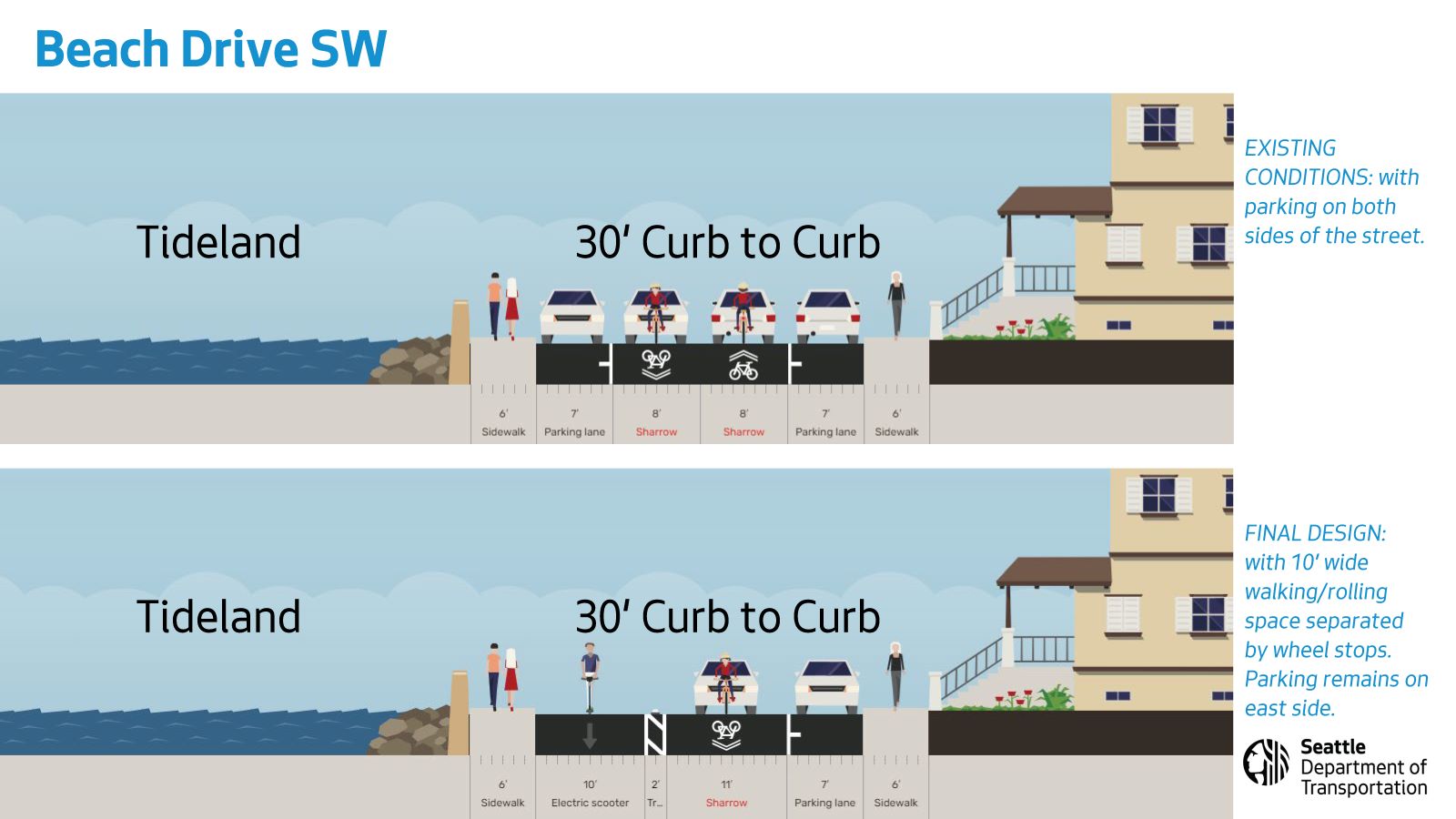

Previously, Beach Drive had been a two-lane street with narrow sidewalks on both sides and two lanes of street parking. With these changes, the west sidewalk alongside Constellation Park has been supplemented by a 10-foot shared walking and biking lane protected by concrete wheel stop barriers. Parking remains in place on the east side of the street, and the one remaining travel lane is open to traffic in both directions, with designated no-parking spaces available for passing. Bike riders along the street can decide whether they’re more comfortable in the traffic lane or in the expanded multimodal space.

SDOT added new American with Disabilities Act (ADA) parking stalls and a new bike parking area. With a few small changes, the priority user of the street was flipped from motorists to people walking, rolling, or biking, while the street remains open to everyone.

“I personally feel like I have a safe space to walk,” West Seattle resident and frequent Alki Point visitor Lynn Drake told The Urbanist. “When I’m walking down there, it’s just a really small, narrow sidewalk [under] the previous design. And I always felt like I had to walk in the street to make room for me and my dog, and people are always walking on the street. And at the same time, cars were in the street, we’re sharing, and some cars are not very courteous, they don’t like that. And they just be outright scary and mean about it. And yeah, it’s scary having to walk on the street.”

In 2020, along with experiments elsewhere in the city in opening streets to people that included closing Lake Washington Boulevard and Golden Gardens Drive to through traffic, Beach Drive saw added signage that simply codified what had been a longstanding practice of people using the roadway, given the incredibly narrow sidewalk. When that proved successful, there was considerable momentum to make improvements permanent with infrastructure. A video created by project boosters in 2020 highlighted problems like street racing that seemed like they could have a solution in physical changes to the roadway.

But the idea of changing the configuration of Beach Drive prompted a considerable amount of pushback, most of which was focused on the planned removal of around 60 parking stalls. That fact isn’t particularly newsworthy, but the discussion on Alki Point came with another added layer: wildlife advocates. A group calling itself “Alki Point for All” was formed to advocate against major changes to how Beach Drive functions, led by folks with ties to organizations whose work deals directly with Constellation Park and its interface with Puget Sound. This advocacy campaign, which has been covered extensively by the West Seattle Blog, looked like it might derail the entire plan at the last minute.

One of these groups is the Whale Trail, which exists to bring awareness of the marine mammals in the Sound, with over 100 sites from British Columbia to southern California where whale watching is encouraged from shore. At a meeting of Alki Point for All in May, the Whale Trail’s founder Donna Sandstrom explained that in their organization’s view, cutting off easy access for people to be able to drive to Alki Point to watch whales would be catastrophic for whale watching in West Seattle.

“I can’t just watch this happen, because this is an end to our programming,” Sandstrom told attendees. “When the whales are here, it’s like a flash mob. A lot of people come to see the whales, they’re gone in an hour or two — the people, not the whales — but that means that less than half the people who previously could watch whales are going to be able to.”

Sandstrom downplayed the impact that people driving directly to Alki Point has on the environment itself, even as drains along Beach Drive aren’t connected to the city’s stormwater infrastructure system but instead lead right into Puget Sound.

“For us, by far, the greater good is to have as many people have direct contact with that ecosystem, and especially the whales, because people protect what they love,” Sandstrom said.

Also involved with Alki Point for All is the Seal Sitters Marine Mammal Stranding Network, a group of volunteers who respond to reports of marine mammals stranded on beaches in order to protect the animals from members of the general public, who are barred by law from interacting with them.

“This is going to have a significant impact on the health and safety of our volunteers,” Seal Sitters’ Victoria Nelson said at the May meeting. Nelson argued that removing parking would make it harder for Seal Sitters to guard the beach while still accessing the equipment they need.

Alki Point for All created an “alternative vision” for the street that, naturally, involved retaining all of the parking and instead applying art to the street as a traffic calming measure. The group also called for removal of the “Street Closed” signs which had actually been installed to comply with state law that doesn’t allow pedestrians to walk along an active roadway while the street is open, but the City took the suggestion to add welcome signs to the street’s entrance and ran with it. New signs with seals and whales now declare “park visitors welcome.”

SDOT also responded to the specific complaints about lack of access for school kids visiting Alki Point on field trips by creating specific loading zones that will be able to be used by buses. It’s also important to note that beachside parking along the south end of Constellation Park, near 63rd Avenue SW, still remains in place.

Alki Point for All was not assuaged by to the City’s attempt to find common ground, calling the changes “not responsive to our concerns.” The group alleges that the street needs to accommodate anywhere from two to 19 school buses and continues to call for retention of all parking with periodic closures of Beach Drive much like South Seattle’s Lake Washington Boulevard today.

However, the compromises were enough to keep the project on track, with Mayor Bruce Harrell’s office apparently sticking behind the project with the understanding that an evaluation would be conducted this fall.

District 1 Councilmember and transportation committee chair Rob Saka, looped into the conversation by Alki Point for All and others, has also signed off on the decision, highlighting that evaluation period. “After extensive communications with impacted communities and SDOT, we are in support of SDOT’s proposed changes to the Alki Point Healthy Street to address the concerns,” Saka wrote to constituents in late May. “While compromises may not fully satisfy everyone, we look forward to continued community involvement in the evaluation report that will be published this fall as to how these changes are working.”

While it’s a bit unclear what exact criteria will be used to determine the project’s success over the coming months, a recent Saturday visit during low tide — a big draw for the natural beach at Constellation Park — showed the street functioning well, with open parking spaces along Beach Drive but more importantly hundreds of people per hour enjoying the corridor in its new configuration. Even though the change had already been in place for a few days, its potential as a model for street reconfigurations elsewhere in the city was clear to see.

Ryan Packer has been writing for The Urbanist since 2015, and currently reports full-time as Contributing Editor. Their beats are transportation, land use, public space, traffic safety, and obscure community meetings. Packer has also reported for other regional outlets including Capitol Hill Seattle, BikePortland, Seattle Met, and PubliCola. They live in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle.