King County Metro’s Route 99, a bus that served the Seattle Waterfront and North Belltown before being cut in 2018, could return in some form. An updated study presents several new options to restore service to some of Seattle’s most visited and densest areas, with potential support from several members of the King County Council.

In the wake of route deletion in 2018, the King County Council requested a report on potential options to serve the area once again. Metro offered three long-term service approaches at the time, but the latest report published last month — in response to a similar council request — adds three more service concepts.

The six concepts vary in how they would partially or fully restore transit to the waterfront and North Belltown areas. Here are the options that Metro has studied:

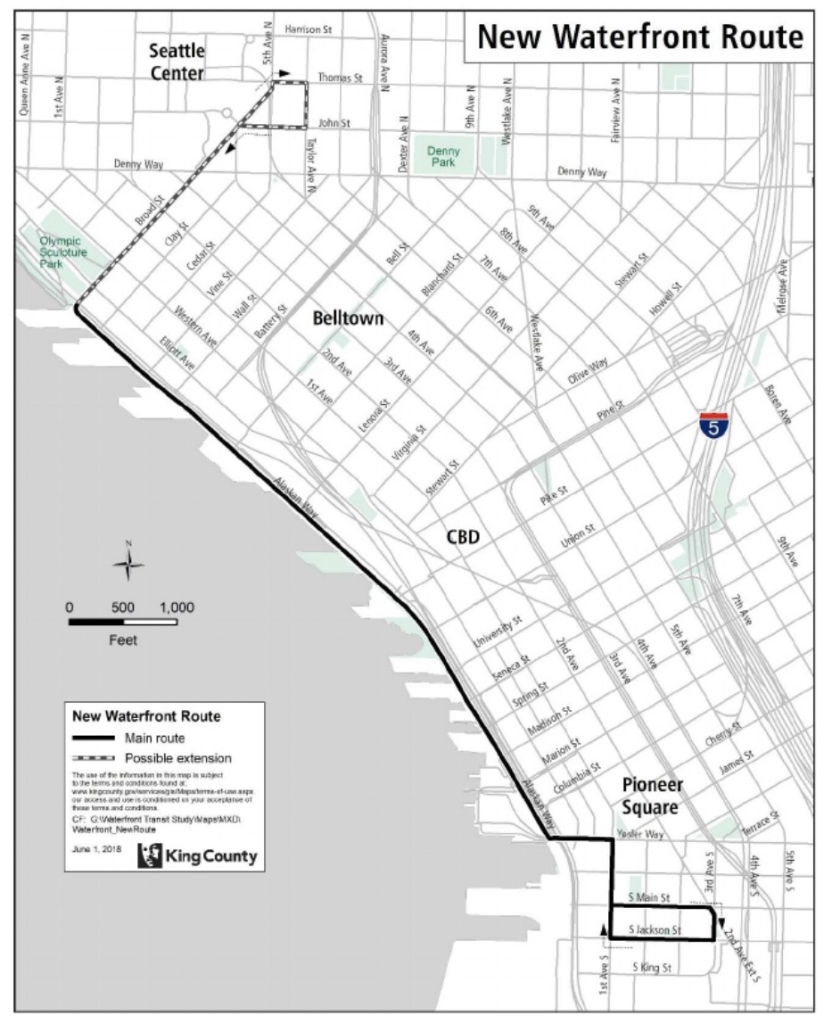

- A new waterfront bus route could run from Pioneer Square to Seattle Center via Broad Street and Alaskan Way using some form of partnership model. In 2018, Metro estimated such a service would require seven battery-electric buses and at least $6.3 million in capital investments.

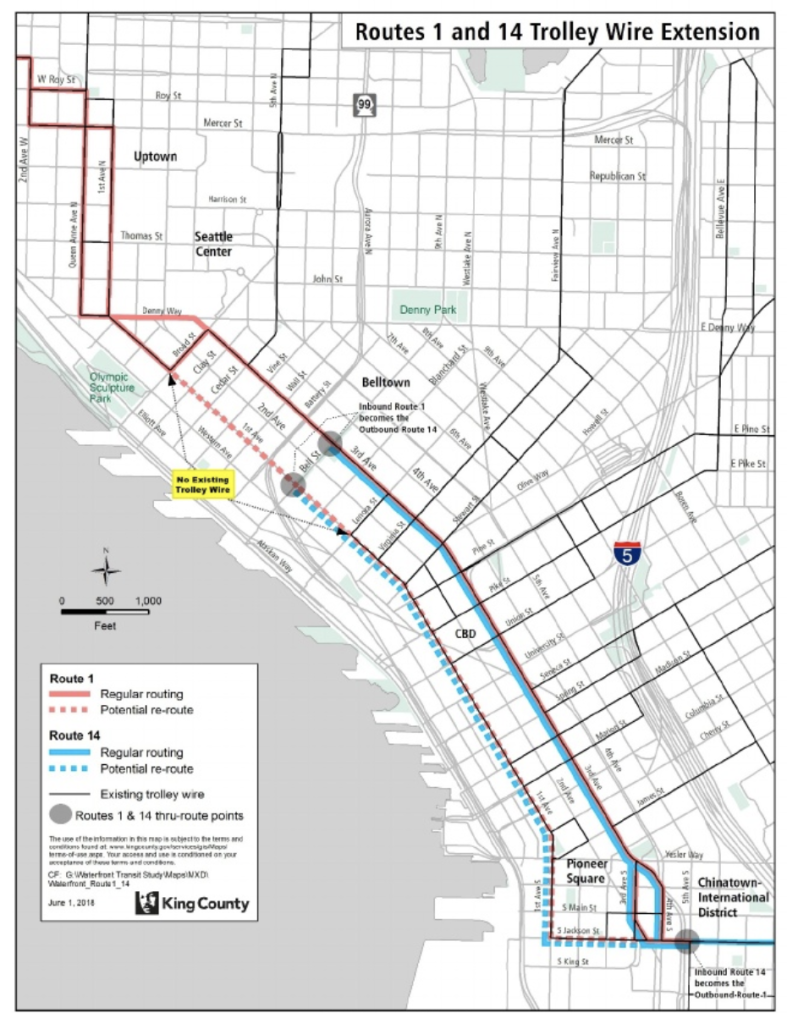

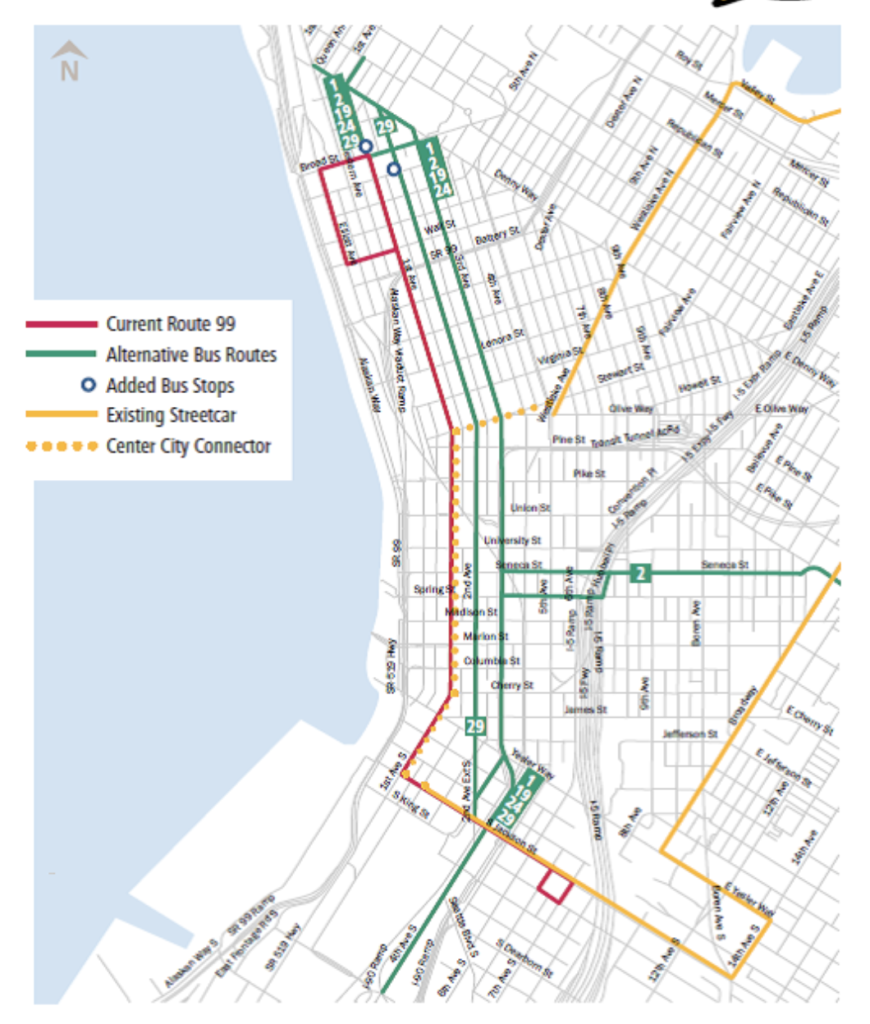

- A trolleybus wire extension on 1st Avenue, between Broad Street and Virginia Street, would allow Routes 1 and 14 to be transferred from 3rd Avenue through Downtown Seattle, though weight restrictions on certain streets in Pioneer Square may be a factor to be addressed with routing. In 2018, Metro estimated costs ranging from $1 million to $4 million.

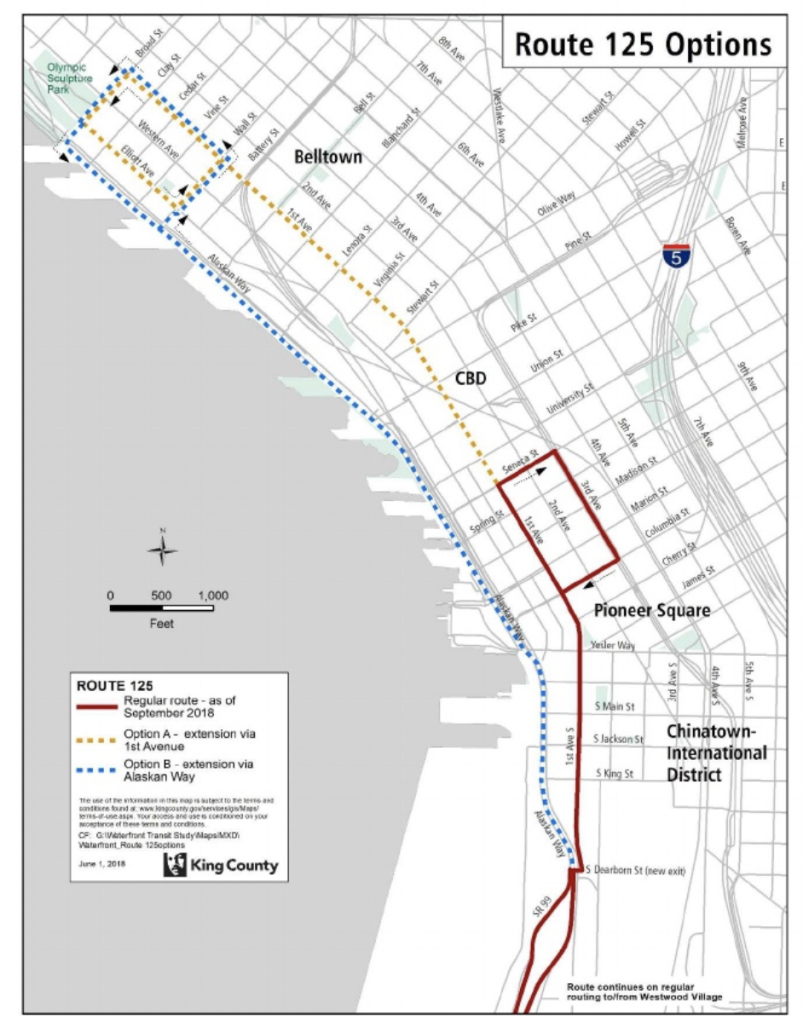

- Route 125 could be rerouted from 3rd Avenue to 1st Avenue or Alaskan Way and extended roughly 11 blocks north to terminate at Broad Street. Metro would need to dedicate one additional bus to facilitate current service levels on the extended route, costing about $750,000 for procurement and another $515,000 per year to operate.

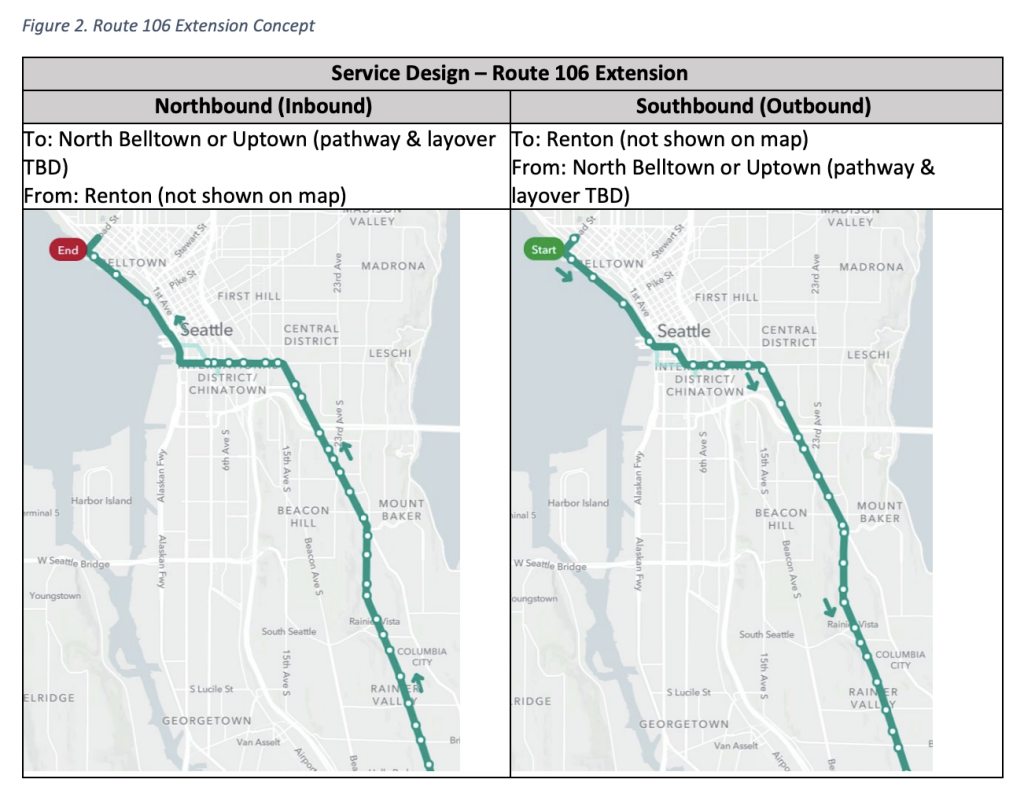

- Route 106 could be extended from its terminus at International District/Chinatown Station to serve Alaskan Way or 1st Avenue, providing frequent and expansive service seven days a week, the 2024 study noted. Drawbacks of this approach, however, include added reliability challenges and routing limitations through Pioneer Square, since some historic streets cannot support the weight of buses. The concept is also contingent upon either finding or constructing a comfort station and layover space on the north end for operators.

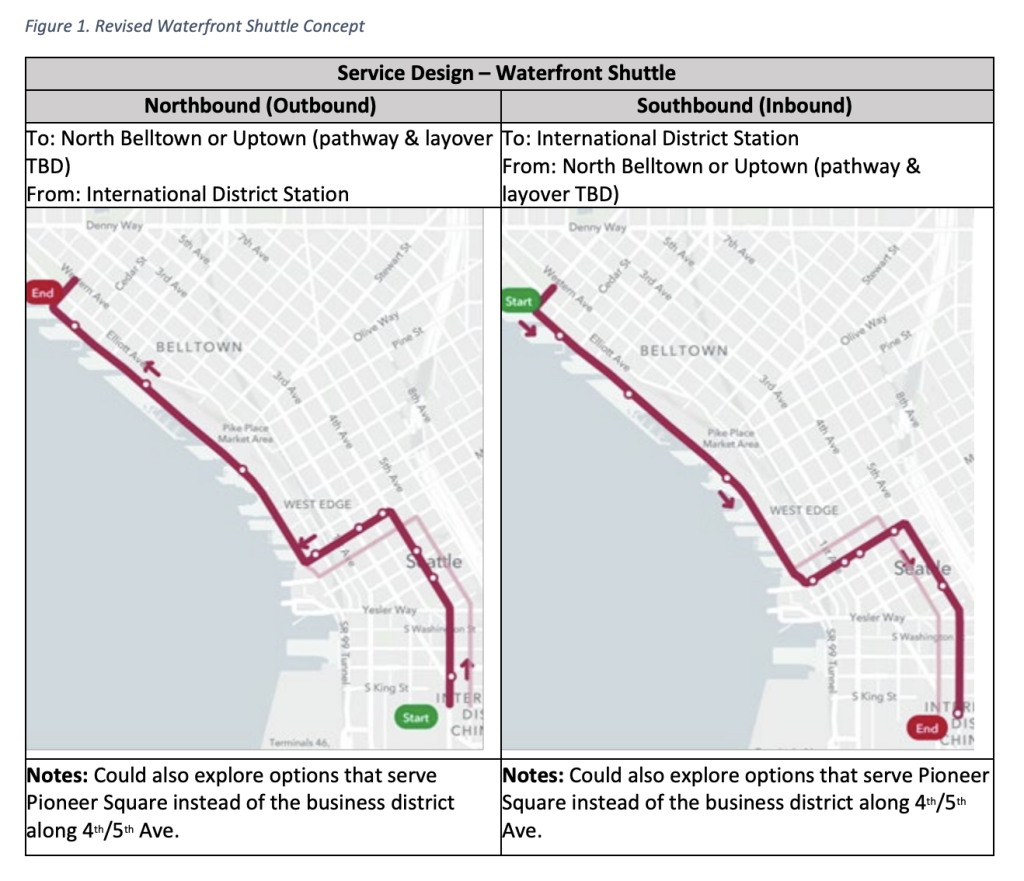

- A revised waterfront shuttle could connect with several neighborhoods, including Chinatown-International District, Central Business District, North Belltown, and potentially Uptown. This could run every 20 minutes from 6:00am to 11:00pm seven days a week, similar to the privately-funded summertime shuttle that currently operates. Like the Route 106 concept, this concept is contingent upon either finding or constructing a comfort station and layover space on the north end for operators. The 2024 report notes that the shuttle concept might not see as much ridership as a fixed-route option.

- A new Dial-A-Ride Transit service route could be deployed, using smaller vehicles and offering flexible, rather than fixed service. Metro has assumed the same hours of operation as the waterfront shuttle and similar vehicles.

For now, Metro has not identified capital and operational costs for the 2024 concepts due to the early planning stage they are in.

In a meeting last month, King County Councilmember Rod Dembowksi (District 1 – Shoreline) asked if restoration of service on the waterfront and North Belltown would constitute new service or replacement service under Metro’s service guidelines.

Mary Bourguignon, the county council’s legislative aide on transit matters, didn’t directly answer the question, but did raise several points regarding Route 99, the former fixed-route Metro bus service on the waterfront and 1st Avenue.

“[Route 99] was in the lowest percentiles of productivity for an urban route under the service guidelines in effect at that time, which meant that it could have qualified for route deletion, even if that hadn’t been necessary during construction,” Bourguignon said. “So it had been a fairly low productivity route, at least in […] the latter years of its service. Metro Connects, the long-range plan adopted by the council for Metro, does not identify a corridor on [Alaskan Way and 1st Avenue]. The corridors are all a little bit further east.”

Bourguignon continued to say the service guidelines are not necessarily the end of the story: “There are, however, options in the service guidelines to add service where service would not be called for by those metrics through partnerships with local jurisdictions or other partners.”

An example of partnerships, though not through Metro, is the existing summertime waterfront shuttle, Bourguignon explained.

“So, during the construction along the [Alaskan Way] Viaduct and for the tunnel, the Washington State Department of Transportation had funded a private waterfront shuttle that provided free hop-on hop-off service during the summer months,” Bourguignon said. “King County has used general fund funding to provide ongoing service during the summers through this coming summer of 2024. That shuttle is not considered transit service — it’s operated by a private operator, it doesn’t charge a fare, it operates only partially during the year, but it has been an option during the busy tourist months.”

King County Councilmembers Jorge Barón (District 4 – Queen Anne) and Teresa Mosqueda (District 8 – West Seattle) both represent the areas that could see restored Metro service, and weighed in during the May meeting.

Barón said that he was especially interested in the trolleybus concept with Routes 1 and 14. He felt it was one of the more viable options, despite the weight restrictions issue in Pioneer Square.

Meanwhile, Mosqueda praised Metro staff for delivering the report and emphasized that addressing transit in the area should be a priority.

“I know that this is not currently part of our [Metro Connects] long-term plan, but it’s important to have this as a template that we could potentially adopt and enhance our long-term strategy for how we can access the waterfront,” Mosqueda said. “I’m thinking of how we make sure people have access to the new and more accessible hours at the water taxi, getting people out of their cars and trying to make sure that people have ways to get around our region that don’t require a car.”

Mosqueda alluded to the SR 99 tunnel project’s lack of transit priority at either end of the new four-billion-dollar tunnel.

“I’m also thinking about ways that we increase access to not only places of employment, but also increase the ability for tourists to enjoy the waterfront,” Mosqueda said. “Especially when we think about 2026 and the World Cup that’s coming, and as someone who frequently gets stuck in the traffic coming north, getting off of [State Route] 99.”

Restoring service to the waterfront and North Belltown isn’t a shoe-in, even if there is some county council support. As noted by council staff, all of the concepts are dependent upon local partnerships (e.g., City of Seattle and private benefactors) and may require local financing since the new service isn’t a priority for Metro right now, and a restructure in the areas hasn’t come into play yet — that would normally be an opportunity to evaluate service changes, including new or extended service. Many of the concepts would also require procurement of new equipment and infrastructure, so Metro would be leaning on partner assistance in delivery, barring different direction and support from the county council.

Each of the concepts come with real tradeoffs. Conventional fixed-route service adjustments like Routes 1, 14, 106, and 125 means that Metro likely wouldn’t directly serve the waterfront via Alaskan Way. Conversely, serving Alaskan Way generally means that Belltown would not be as well served with transit, even if routes reach North Belltown. Service on 1st Avenue represents a significant expansion in transit access because much of the corridor is considerably lower in elevation than 3rd Avenue, the city’s main transit artery, and would be better activated with linear transit service.

In a better world, both the waterfront and 1st Avenue corridors would be served by all-day, frequent, all-year-round surface transit and make use of the city’s dormant trolleybus wires — which provide for the greenest form of bus service in Metro’s fleet.

A waterfront trolley is not unprecedented. Before there was a Route 99, the Seattle Waterfront was served by the George Benson Waterfront Streetcar Line between Pioneer Square and the present-day Olympic Sculpture Park via Alaskan Way, using heritage streetcars from Melbourne. The line ran from 1982 until its hiatus in 2005 to accommodate construction of the sculpture park, which necessitated removal of the streetcar barn. The City had discussed building a new streetcar barn, but it never transpired, and tracks were pulled up to support the Alaskan Way Viaduct Replacement project, ending hopes of a return of the waterfront streetcar for the foreseeable future. Instead, the Route 99 bus was put into service as a replacement.

Policymakers certainly have their work cut out for them in paving a way forward, but restoration of some form of service has plenty of good cause, as Mosqueda noted. The timing may be right with the indefinite shelving of the Center City Connector, a project to bring streetcar service to 1st Avenue by constructing new tracks and extending the South Lake Union and First Hill Streetcar Lines into a unified network. However, time will tell if this report is just another study sitting on the shelf to gather dust or a call to action that begets a return of Metro service.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.