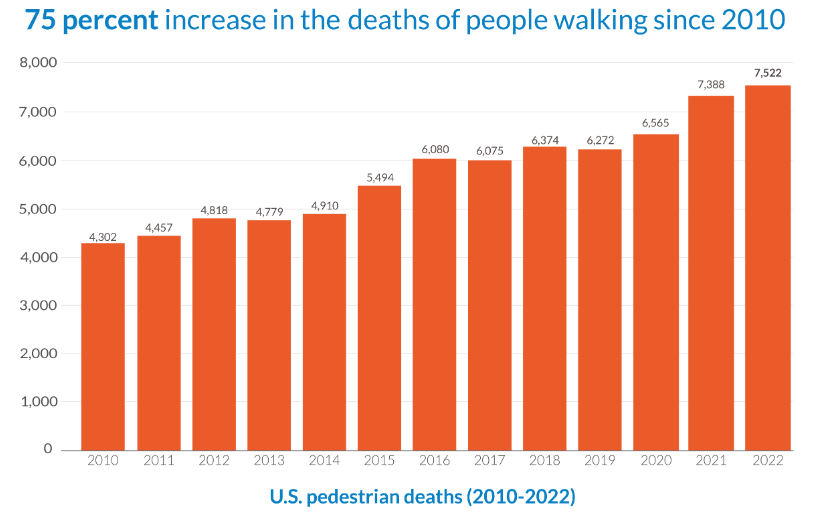

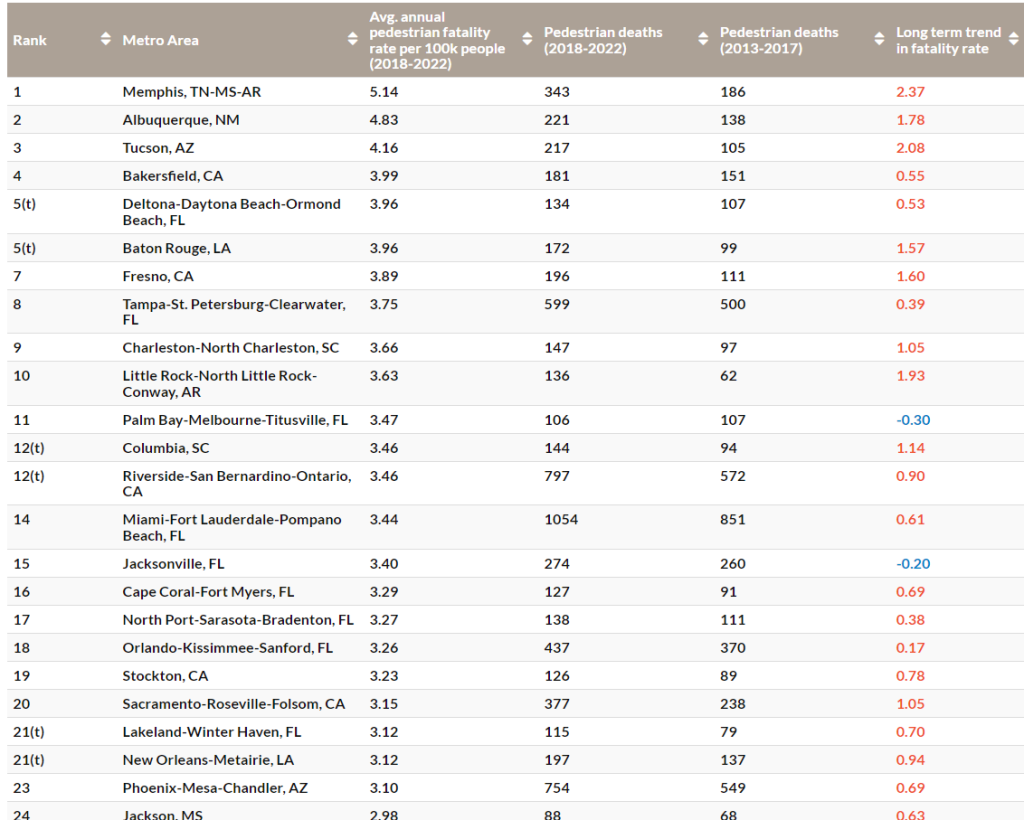

Smart Growth America recently released Dangerous By Design 2024, a national report tallying the number of people killed while walking and ranking the 101 largest U.S. metro areas by their fatality rates. The report paints a grim picture of traffic violence in the U.S. 2022, the most recent year for which complete federal data has been collected, marked a 40-year high for pedestrian deaths in the U.S. – 7,522 people were killed, an increase of 57% in a decade. In 2013, 4,779 pedestrians died, for comparison.

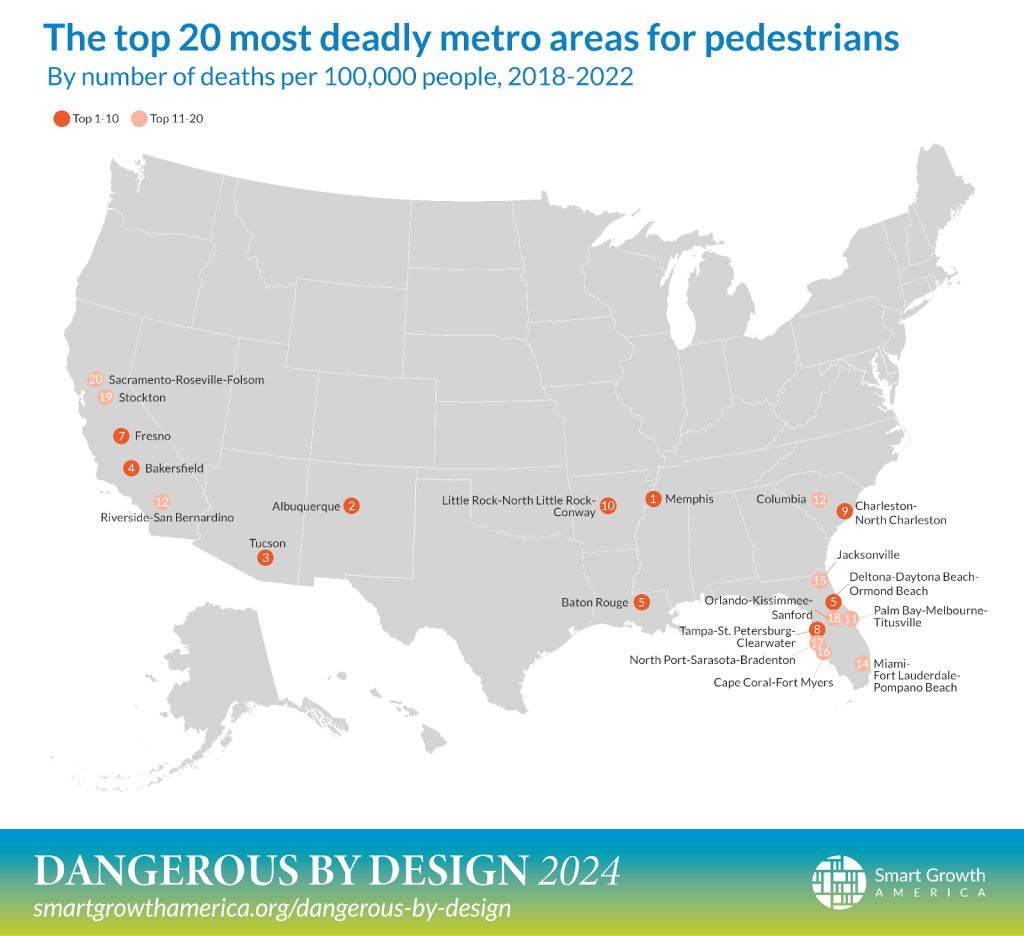

Serious injuries have spiked as well – between 2021 and 2023, the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) documented 137,325 emergency room visits for pedestrian injuries. Data shows that traffic violence is highest in the South and West, with metros like Memphis, Albuquerque, Tucson, and Bakersfield, Calif. topping the list.

Beth Osborne, Vice President of Transportation and Thriving Communities at Smart Growth America, emphasized that the problem of traffic violence exists in all U.S. cities at “levels not seen in peer nations.”

“Everywhere [in the U.S.] has gotten so much worse,” Osbourne said in a media briefing last week. She pointed out that 82% of metro areas have become more deadly over time, according to the data in the report.

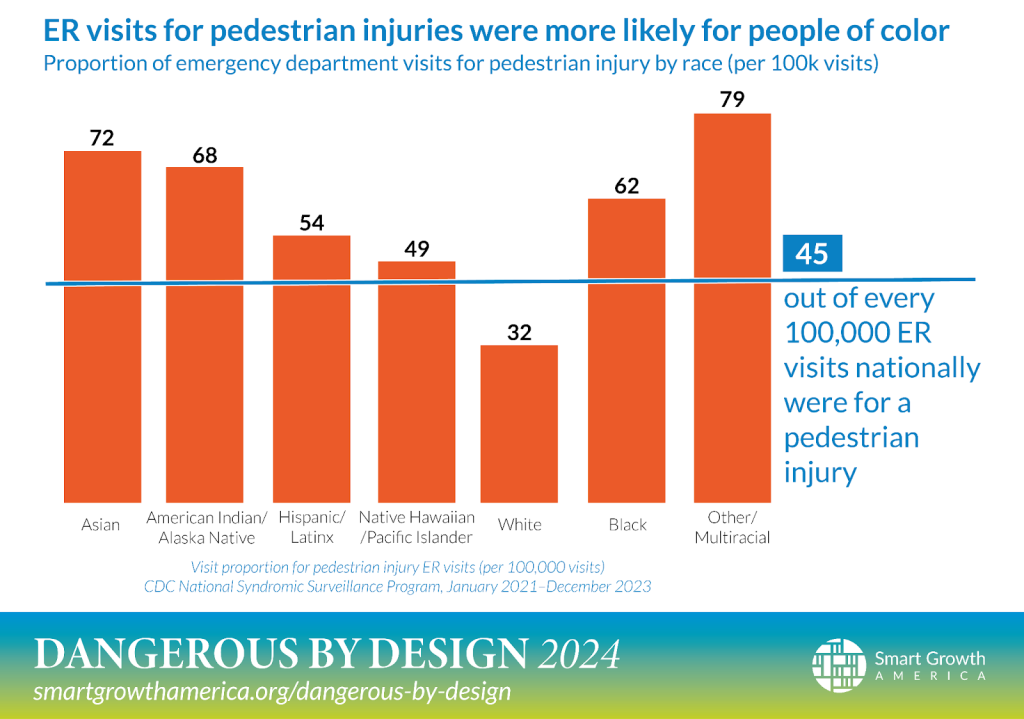

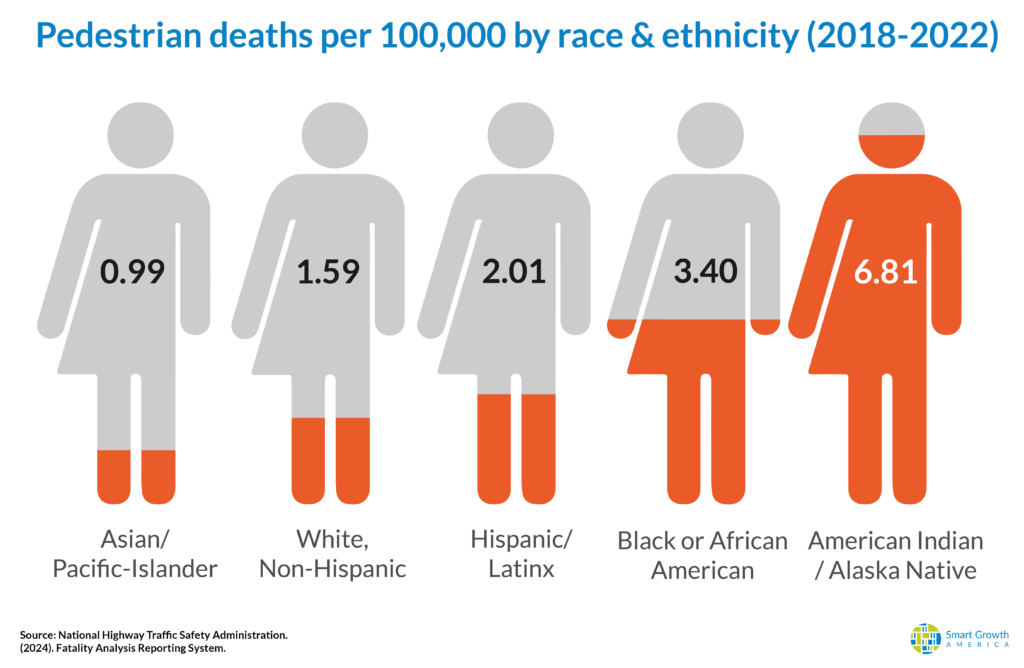

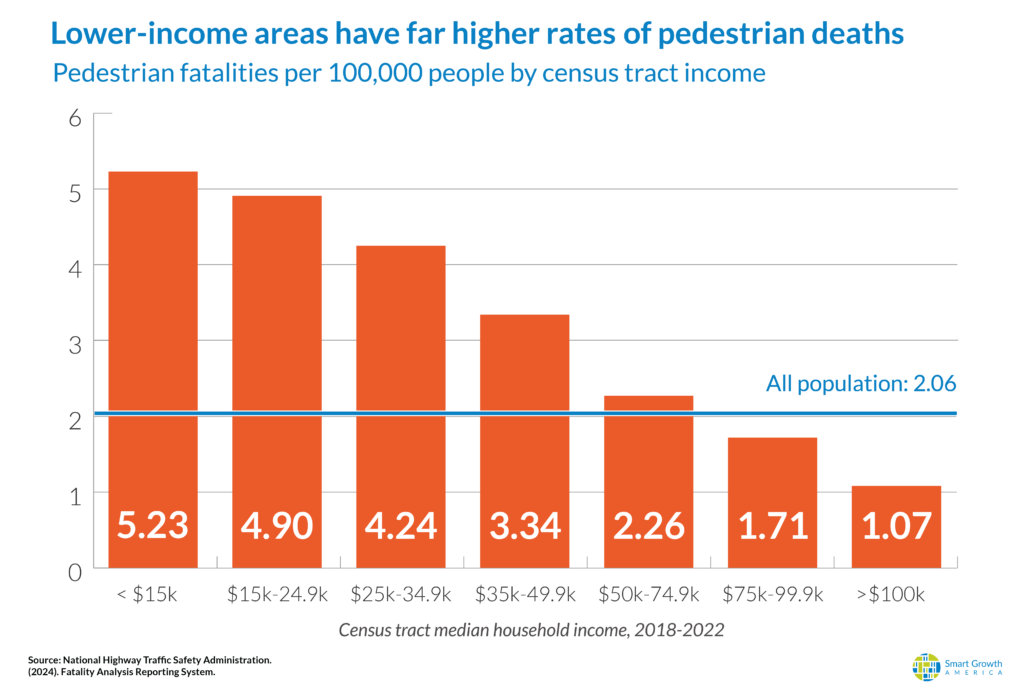

Traffic violence has a disproportionate impact on communities of color. Race and income are tied to how likely a person is to be struck and injured or killed while walking. The report found that a Black person is twice as likely as a White person to be struck by a vehicle while walking. Native Americans are four times as likely to be struck.

The most dangerous neighborhoods for pedestrians in cities tend to be found in lower income neighborhoods, and state-owned roads, like Aurora Avenue (SR 99) and Rainier Avenue (a decommissioned state road) in Seattle, are disproportionately the site of crashes that injure and kill pedestrians. Dangerous By Design 2024 found that within the 101 largest U.S. metro areas, 66% of all traffic deaths occur on state-owned roads, which are often designed as major thoroughfares with multiple lanes of traffic and high speed limits – even in populated urban centers.

The Seattle metropolitan area is middle of the pack in the report, with the 64th highest pedestrian fatality rate per capita. Memphis has a pedestrian death rate that is more than three times higher than in Seattle, but standout metropolitan areas like Madison, Wisc. and Provo, Utah have managed to halve their rates compared to Seattle’s and avoid the negative trendline that Seattle and most American cities find themselves in.

My aunt’s death highlights the problem of underreporting

As staggering as it is, the official count of pedestrian deaths is far from complete. Many pedestrian deaths are never logged with the authorities due to incomplete reports on the scene or the death happening days later due to complications from the collision. This is something I learned firsthand when my aunt, Marjorie Bicknell, died after being hit by a car while walking last fall.

On a Sunday afternoon in October, Marj was struck while crossing the street at the intersection of Spruce and South Broad in central Philadelphia. She had recently left a theater performance and was walking home at the time of the collision. An off duty medic saw what happened and immediately stepped in to call 911 and ensure life-saving measures were performed until she was rushed to a nearby hospital. But it wasn’t enough. About two weeks later, after suffering multiple bone fractures, bleeding and swelling in her brain, pneumonia, intubation, and strokes, Marj died of cardiac arrest.

Marj was in excellent health and a whirlwind of purpose and energy at the time of collision. Her tragic death devastated many people – including the theater community in Philadelphia where she was an actress, award-winning playwright, president of Philadelphia Dramatists’ Guild, and beloved mentor to many aspiring writers and performers.

But probably because she was otherwise in good health and was quickly attended to by medics, the police crash report logged her injuries as “of unknown severity.” As a result, when my family inquired, we learned her death had been not documented as a pedestrian fatality.

Quite frankly, if I had not had years of experience reporting on traffic violence, I don’t think that we would have even looked into whether or not Marj’s death had been properly documented as a pedestrian fatality. We also most likely would not have known how critical it was for her death to be properly reported or known who to contact to make sure it did not go uncounted.

In our case, the advocacy group Families for Safe Streets Greater Philadelphia added her data to their records on traffic violence and offered support as we learned more about the details of the collision and court case involving the driver who struck her.

Experts from Smart Growth America confirmed the lack of accurate data on pedestrian deaths and injuries distorts our understanding of the epidemic of traffic violence, and is a significant problem to overcome.

“We do not know [how many incidents go unreported], and it’s not just a question of how many people go on and die later… Serious injury is often not known at the site of the collision, especially with concussions,” said Beth Osborne, Vice President of Transportation and Thriving Communities at Smart Growth America. “I know of people who have gone on to a lifetime of health challenges due to concussion that wasn’t diagnosed for months after a crash.”

While hospitals are supposed to convey information on deaths and serious injuries back to the police to update the crash report, this does not always happen in practice, Osborne said. In cases like my aunt’s, where the victim experiences a succession of traumatic health events and a long hospital stay in the aftermath of a collision, it may be easy to overlook the actual cause of death was being struck by a vehicle.

“We are working more with the CDC who has done some excellent work with hospitals to collect these data and better count them,” Osbourne said, “and I know they [the CDC] are trying to work with the USDOT to do better in collecting those data so people can better understand the magnitude of the challenge.”

Measure what matters

Heidi Simon, Director of Thriving Communities at Smart Growth America, said having more accurate counts of deaths and serious injuries, as well as near misses, “could help us to be more proactive about the crisis.” Simon emphasized that the traffic and transportation data that is captured is a result of what we “choose to pay attention to and prioritize.”

As many advocates for safer streets have learned through long struggles, ensuring safety for people who walk, roll, and bike is not often treated as the highest priority by transportation departments and the policymakers guiding them. Instead, the focus is often on the speed and throughput of motor vehicles.

“The standard for street design is highway-based,” said Osbourne, explaining the challenges engineers often encounter when trying to design for “complete streets,” which are aimed at ensuring the safety of people traveling in vehicles and people walking and biking.

“These engineers are still swamped by standard, and many times [they] need to go through an exemptions process because this kind of project deviates from the standard,” Osbourne explained.

Calvin Gladney, President and CEO of Smart Growth America, succinctly summed up what seems to be the general response to pedestrian death in the U.S. “It’s just the cost of business that people walking get killed every day.”

A tragic epidemic fueled by inaction

At Marj’s memorial service and burial, I had the chance to speak with several of her friends from Philadelphia. No one was surprised by what had happened – or where it happened on busy South Broad Street.

While people were shocked by the fact Marj had died, the fact that a car had struck her while walking did not seem to provoke disbelief or outrage. I have to believe that this is because Americans as a whole have become desensitized to traffic violence and accept it as a fact of life.

That doesn’t make the toll any less high. We should be shocked and outraged every time a person is struck by a vehicle and injured and killed. As I write this now, it still feels unreal to me that Marj – a big-hearted, smart, generous, and dynamic person – was killed simply because she decided to walk home.

In the weeks after the funeral, we learned that Marj was walking in a marked crosswalk with the pedestrian light at the time of the crash. But the vehicle that hit her also had the right to go and was not cited as traveling above the posted speed limit of 30 miles per hour. While the driver should have yielded to her, it is likely they did not see her. Chaotic interactions tend to ensue when a busy six-lane boulevard like South Broad Street interacts with a dense urban environment with lots of pedestrians.

“I guess her death was the cost of living in a motorized society,” my father said in response to the news, trying to make sense of the loss of his sister, which hit him very hard.

It was a bit comforting for my father to learn that Marj had not broken any traffic laws, but this knowledge actually made me feel worse – probably because of my work reporting on traffic violence. The circumstances of her death clearly demonstrated how so many of our streets are designed as traps for people who walk, even when pedestrians and motorists follow the rules supposed to keep us safe.

We have the blueprints for safe streets

Smart Growth America’s Dangerous By Design report series shows our roadways are designed to be dangerous for all users. Moreover, transportation agencies are slow to make the changes proven to make people safer – such as designing roadways to be narrower and to have shorter blocks, raised pedestrian crossings, and narrower lanes, so that drivers feel constrained and naturally drive slower and with greater caution.

“We have chosen in this country to not utilize those well-known principles in the design of roadways to get the behavior that we would like to see,” Osbourne said.

Traffic violence in the U.S. is trending in the wrong direction, but Osbourne said solutions are available; we know how to design roads to be safer for people who walk. We can continue to live in a motorized society and not subject people to cruel deaths and injuries. It will take resources, planning, and political will – but it is possible.

I am going to keep advocating for safer streets and hoping that the necessary change will come because my aunt Marj – and the countless other victims of traffic violence – deserve it.

Natalie Bicknell Argerious (she/her) is a reporter and podcast host at The Urbanist. She previously served as managing editor. A passionate urban explorer since childhood, she loves learning how to make cities more inclusive, vibrant, and environmentally resilient. You can often find her wandering around Seattle's Central District and Capitol Hill with her dogs and cat. Email her at natalie [at] theurbanist [dot] org.