The Sound Transit board established a new set of lower farebox recovery goals for buses and trains in a vote last month. The new targets follow the adoption of a new $3 flat fare structure for Link light rail, approved in December and slated to go into effect on August 30 when the Lynnwood Link Extension opens.

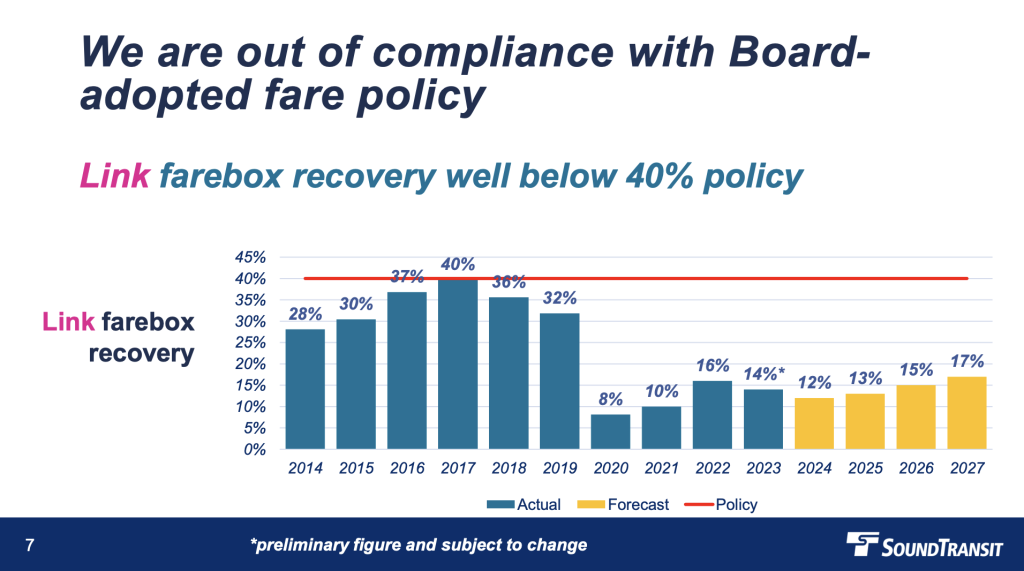

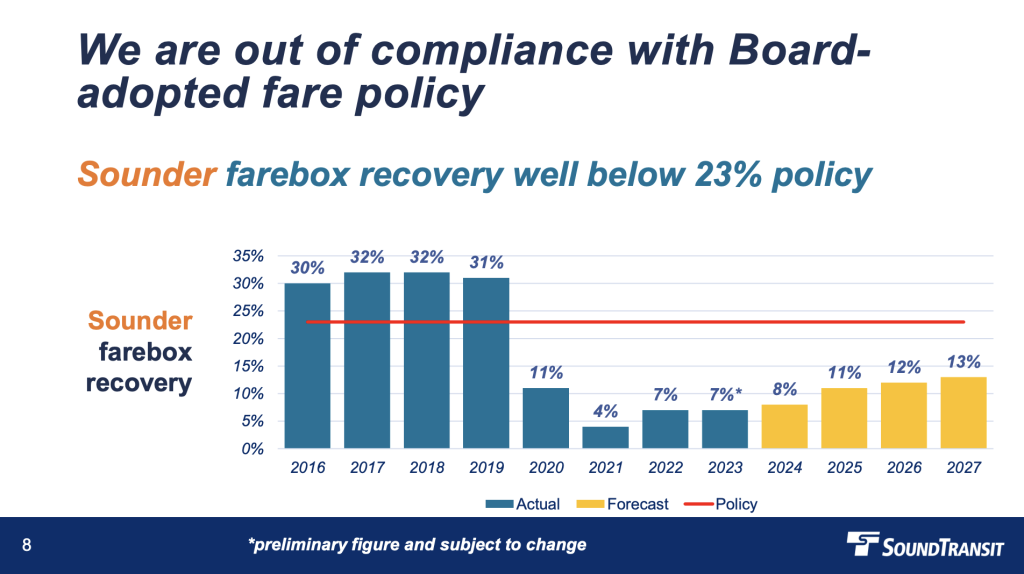

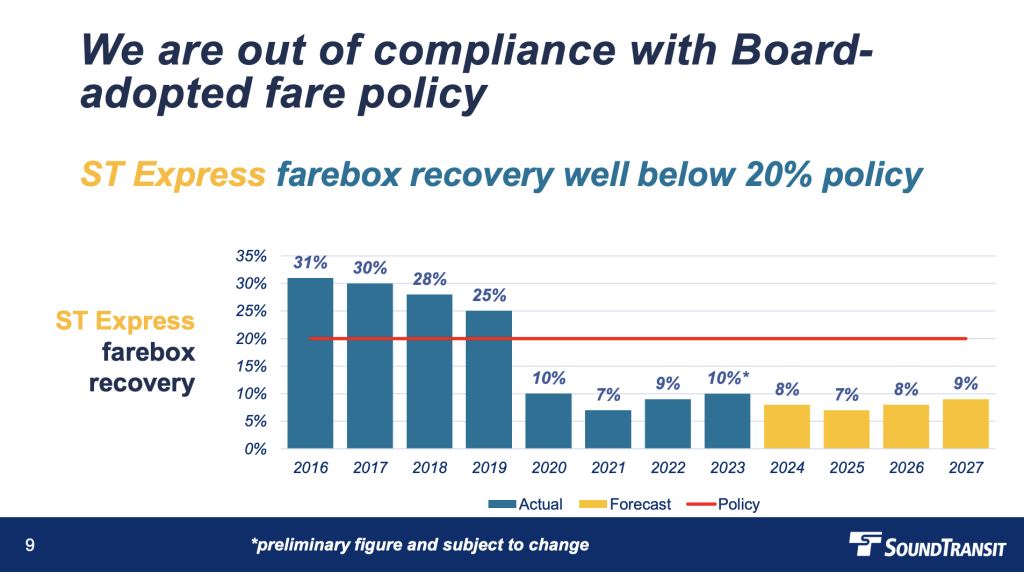

Farebox recovery rates — the ratio of how much a fare covers operations and maintenance costs for a trip — have fallen precipitously across all service types since the pandemic hit in 2020. This is in large part due to lower ridership levels, but also stems from higher rates of fare evasion and increased operations and maintenance costs. Operational costs are likely to balloon even more as Sound Transit expands its light rail network to 116 miles over the next two decades, continuing to put pressure on operations and farebox recovery goals.

Ridership has been rebounding every year since the height of the pandemic, but Sound Transit’s total ridership has not yet recovered to the highs of 2018, when the agency registered 48.2 million rides. Last year, riders posted about 37.4 million rides, leaving the agency 10.8 million rides short of their historic highs. That means Sound Transit is still down about 25.2% in systemwide ridership, even with the opening of a major three-station Link expansion via the Northgate Link Extension in 2021.

Meanwhile, Sound Transit estimated that about 45% of Link riders did not pay with valid fare media as of October 2023. That fare evasion rate is much higher than the agency’s 2.4% estimate prior to the pandemic in 2019.

Sound Transit projects that its Link fare evasion rate will drop to 25% by 2029, but the agency anticipates spending considerable sums of money on a new fare compliance program that will require about twice the staffing to implement. Despite calls from a few agency boardmembers, a push to implement fare gates to combat fare evasion seems to have stalled out.

Sound Transit’s long-range financial plan is built upon fares paying for a meaningful proportion of operations and maintenance costs. Between 2017 and 2046, the agency forecasts around $5.5 billion in fare revenue. The financial plan is predicated on attaining a systemwide farebox recovery rate of at least 15% with a target of 20%. As a result, Sound Transit sought to update its formal fare policy to reflect those rates, which are much lower than pre-pandemic levels, and make procedural changes in how fares are adjusted.

Alex Krieg, a Sound Transit planner, briefed the agency board last month on the then-proposed changes. “The updated policy modifies the existing targets to include a minimum threshold, as well as a target the proposed minimum thresholds aligned with fair revenue projections in our finance plan,” he said. “The updated policy includes a systemwide farebox recovery minimum and target to give us a broader understanding of overall fare revenue performance.”

Sound Transit’s revised policy sets minimum thresholds and target farebox recovery rates for Sounder commuter rail, ST Express bus, and Link light rail services in addition to a systemwide standard. This shakes out as follows:

- For Sounder, a minimum of 13% with a target of 18%,

- For ST Express, a minimum of 7% with a target of 12%,

- For Link, a minimum of 17% with a target of 22%, and

- Systemwide, a minimum of 15% with a target of 20%.

Immediately before the pandemic, Sound Transit was reaching farebox recovery rates of 32% on Link, 31% on Sounder, and 25% on ST Express. Link hit a record high 40% farebox recovery in 2017, but farebox recovery began to dip in the intervening years, until plummeting to just 8% at the height of the pandemic.

“While this is a significant decrease, I want to note that the 40% target has existed since the original Sound Transit master plan from 1994 — before we ever operated a light rail system and when the original Sound Move vision from 1996 was a single line operating between Northgate and SeaTac,” Krieg told boardmembers. “When fully built out, our light rail system will span from Everett to Tacoma and from Issaquah and Redmond to West Seattle and Ballard, which is obviously much larger than originally envisioned and will cost more to operate.”

In other words, high farebox recovery ratios are not often compatible with high-frequency light rail systems that run deep into sprawling suburbs, which is the goal of Sound Transit’s light rail spine.

Krieg added that the ST Express and Sounder farebox recovery rate reductions were comparably modest to Link, but were being adjusted downward nevertheless because of reduced ridership in the post-pandemic environment — particularly on Mondays and Fridays for Sounder. The highest productivity ST Express routes being replaced by Link expansions has hurt farebox recovery for the bus program.

As part of the revised farebox recovery rates, the new policy establishes an automatic, periodic review process for evaluating fare changes. “At least once every four years, the board must consider fare changes and review operational expenses by mode that impact the farebox recovery ratio and long-range financial plan,” the policy states.

The trigger for a fare change proposal that the agency board must consider is whenever the farebox recovery rate falls below an established minimum rate for more than two consecutive calendar years. “The rationale for two consecutive years is that this will accommodate outlier circumstances like major maintenance activities that may result in one year underperformance,” Krieg told boardmembers.

However, Puyallup Mayor Jim Kastama, a relatively new boardmember, questioned the policy changes. “These seem like really drastic changes, actually,” he said. “Let me ask you, what prevents a minimum from becoming the maximum?”

Krieg responded by saying that the farebox recovery targets would still be the goal, but that the minimums would act as a baseline for meeting fare revenue projections in the long-range financial plan. If the minimums aren’t being met, Krieg said, “that really is the indicator that we’re off track.”

Kastama countered in response, “You just said, if you don’t meet the minimum, not if you don’t meet your target, which means, again, the minimum kind of becomes a maximum.” He further pushed Krieg to confirm that the minimums are what the agency is doing now, not an aspirational goal.

Based upon the revised policy, Kastama’s assessment is a strong possibility, since inflation will increase the cost of operations and maintenance and existing fares will lose effective value the longer they remain unchanged. The main path to reach farebox recovery targets is booming ridership beyond growth estimates and lower fare evasion rates, but neither is assured.

The loss of fare value to inflation is a real challenge for the agency, especially because of the risk that the minimum farebox recovery targets simply become the status quo. Rising operational costs could push Sound Transit to raise fares every four years. The custom within the regional transit fare program (ORCA) dictates that large fare changes should happen in increments of 25 cents. That could mean potentially raising Link fares by 50 cents to $3.50, for instance, in the next go-around just to match inflation and not other potential operational cost increases.

Other transit agencies in regions like New York City, London, and Vancouver, British Columbia typically raise fares in much smaller increments but more frequently, retaining the effective value of fares. Sound Transit could have done similar in the updated policy by automatically increasing fares based upon yearly or multi-year smoothed inflation rates with a periodic evaluation that the new policy calls for, offering a smoother path to achieve farebox recovery goals.

The new fare policy comes with some other important features.

First among those is the addition of fare capping to the policy, which, if implemented, would allow riders to reach a maximum fare before each additional trip is free. When and how this will be implemented remains unclear, but Sound Transit is working with regional partners to bring fare-capping to ORCA, which could potentially apply daily, weekly, and monthly.

Second, the new policy also requires that the agency board adopt minimum and target farebox recovery rates for all new modes three years after commencing service or fare collection. This is meant to capture services like the expanded T Line streetcar (formerly Tacoma Link) that converted to a fare-paid service last year and the Stride bus rapid transit network set to launch later this decade, but to temporarily delay establishment of formal rates in these cases so that Sound Transit has time to properly evaluate and let ridership and operating expenses settle.

Third, the policy formally adds flat fare and route-based categories as additional possible fare structure types, joining distance- and zoned-based fares. This enables the agency to consider using a standard fare regardless of distance traveled — a strategy increasingly being applied to Sound Transit services — and applying special fares to a particular route based on its service characteristics or market served.

Lastly, the new fare policy further maintains that future fare change proposals must consider potential fare structure changes, not just fare rate changes. That would allow Sound Transit staff to consider an equitable zone-based fare structure for the sprawling Link system in four years’ time, undoing the Link fare flattening from last fall that — once it goes into effect in late August — will heavily subsidize suburban riders traveling long distances and penalize urban riders traveling short distances.

Stephen is a professional urban planner in Puget Sound with a passion for sustainable, livable, and diverse cities. He is especially interested in how policies, regulations, and programs can promote positive outcomes for communities. With stints in great cities like Bellingham and Cork, Stephen currently lives in Seattle. He primarily covers land use and transportation issues and has been with The Urbanist since 2014.