Rejecting notions of austerity doesn’t mean much unless we embrace progressive revenue that allows Seattle to invest in its future.

The City of Seattle has a quarter-billion-dollar budget problem to solve. In his “state of the city” speech earlier this year, Mayor Bruce Harrell said he rejects notions of austerity. Good for him! I’m here to help. Let’s chart a way out of this crisis that doesn’t involve slashing city services, laying off city workers, and hobbling our progress on housing and homelessness. In other words, let’s talk about taxing the rich. But first, a brief primer on how we got here.

How did we get here?

The City’s $1.7 billion general fund is its most flexible pool of money and comprises just over a fifth of the total budget. Base revenues flowing into that fund have fallen short of expenses for some years now. Why? A host of factors, which mostly boil down to the economic blow dealt by the Covid pandemic, roaring inflation, the (consequently) rising cost of paying city workers, and the state-imposed 1% annual limit on general-purpose property tax rate increases.

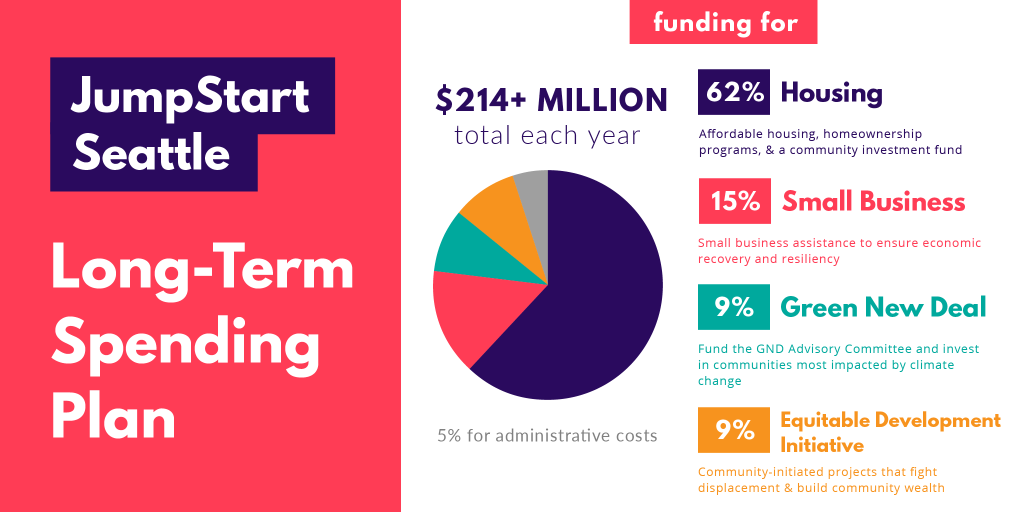

So far, that gap between revenue and expenses has been masked by the addition of temporary funds, including federal pandemic relief dollars and infusions from the JumpStart big business tax that was passed in 2020. JumpStart’s long term spending plan focuses on affordable housing, equitable development, small business support, and climate resilience, but the tax also came to the rescue during the pandemic, preventing the deep cuts many other cities have had to make.

But starting in 2025, those one-time transfers disappear and a yawning shortfall opens up, most recently estimated at $258 million or about 15% of the general fund.

We’re already getting a taste of what the fallout might feel like. Seattle Public Library announced 1,500 hours of closures this spring, after an anticipatory hiring freeze made staffing shortages worse. This year over 60% of the library’s funding, or $62 million, came from the general fund.

What else could be on the chopping block? Almost half the general fund goes to public safety, which (just being real here) seems unlikely to get a haircut — Mayor Harrell has exempted public safety departments from the hiring freeze he put in place in January. But other general fund beneficiaries, from the libraries to human services to arts and culture to transportation, may be in peril.

The other obvious move is to toss out the JumpStart spending plan, slashing the City’s future investments in affordable housing and diverting that revenue to fill the general fund hole. (It’s already begun.)

But why are we talking about cuts? Harrell says he’s not an austerity mayor, so let’s talk about new revenue instead. Specifically, let’s talk about taxing the person who will be moving into that multimillion dollar penthouse at the top of the First Light condo tower, soaking in the rooftop jacuzzi and vrooming around downtown in a McLaren supercar. Let’s talk about taxing the rich. How could we do it, if the political will were there? Let us count the ways.

1. Capital gains tax

Our future penthouse owner needs to sell off some assets to plunk down that $5.1 million. When they do, Washington state will be taking a cut. In 2021, the legislature passed a bill that taxes capital gains in excess of $250,000 at a rate of 7%. This was challenged in court as an illegal graduated tax on income, but last year the Washington State Supreme Court ruled that it’s actually an excise tax. This decision paves the way for Seattle, which has broad authority to levy excise taxes, to adopt its own local capital gains tax.

Some other US cities tax capital gains, including San Francisco and New York, but they do so by default as part of a broader tax on income, and their local income taxes are an added increment on top of a state income tax. A local capital gains tax not paired with an income tax would be a first. (Thanks to Brian Heywood, Seattle will not be passing an income tax anytime soon, though that would be an excellent way to tax the rich.)

Last fall, City staff estimated that a 2% local capital gains tax, structured just like the state tax, could raise $38 million in its first year. A few percentage points on top of the state’s 7% isn’t going to solve the general fund problem, but it would make a dent. This is a volatile revenue source, as we’re seeing at the state level now, so the City couldn’t count on consistency from year to year. But it would likely be popular.

There’s one big political wrinkle, of course: This fall, Washington voters will decide whether to repeal the state capital gains tax. Until that’s settled, it’s hard to imagine city leaders taking up a local version, even if they were enthusiastic about the idea. But next year, they should.

2. Wealth tax

Seattle already taxes wealth — in the form of real property, like land and houses. If you’re a middling homeowner, most of your wealth is tied up in your home, and you’re paying taxes on it. If you’re a renter, you’re still indirectly paying property taxes, even though you don’t enjoy the benefits of ownership and may well have zero or negative wealth. But if you’re very rich, like the future inhabitant of the First Light penthouse, you’re probably also sitting on a huge pile of intangible assets, such as stocks and bonds. And those are tax free.

So how about taxing intangible wealth? The Pennsylvania Budget and Policy Center has proposed that the City of Philadelphia do just that. Pennsylvania counties have a long history of taxing intangible wealth, but these taxes were repealed in the 1990s after a successful court challenge. In 2022, several Philadelphia councilmembers supported a new, improved version, a 0.4% tax that PBPC estimates would generate between $240 and $280 million a year. But it hasn’t moved forward since.

Here in Washington, a state-level wealth tax has been a hot topic in the last couple legislative sessions. In 2021, HB 1406 was proposed to “[improve] the equity of Washington state’s tax code by creating the Washington state wealth tax and taxing extraordinary financial intangible assets.” This one percent tax would have exempted the first $1 billion of assessed value. A new version proposed in 2023 (HB 1473 and SB 5486) lowered the exemption to $250 million and was estimated to raise $3 billion annually.

Could Seattle tax intangible wealth? Whether passed at a state or local level, such a tax would surely face legal challenges. Even if it withstood those challenges, administering and enforcing a city-level wealth tax would be difficult. Look, I’m not saying all these ideas are slam dunks! But it’s worth a try. If Philadelphia can go there, so can we.

3. Mansion tax

When the First Light penthouse is eventually sold, the City will collect a real estate excise tax (REET) amounting to 0.5% of the sale price. When a more modest home changes hands, that transaction is taxed at the same rate.

But some cities have so-called mansion taxes, with steeper rates for high-dollar property transactions. In 2022, Los Angeles voters approved a 4% tax on property sales above $5 million, rising to 5.5% on sales over $10 million. It’s raising hundreds of millions a year — and stirring up a lot of controversy. San Francisco and New York City also have progressive real estate transfer taxes with graduated rates, rising to 6% on property sales above $25 million in San Francisco and 3.9% in New York.

Washington adopted a similar approach for our state-level REET in 2020. Sellers pay graduated rates topping out at 3% for sale value in excess of about $3 million. Last year, House Bill 1628 proposed an additional tier, a 4% tax on property sale value in excess of $5 million. That bill did not pass.

Seattle’s REET authority is regulated by state law, so to increase the rate or create a graduated structure would require permission from the legislature. Even a flat 0.25% bump (which was also part of HB 1628) is a fine way to tax the rich. New tiers with higher rates for sales in excess of $3, $5, or $10 million would be even better. You could also imagine adding a surcharge specifically for ‘McMansion’ sized homes, typically defined as greater than 3,000 square feet.

REET revenue has taken a dive with the cooling real estate market, mostly due to high interest rates and cratering office demand. That’s another city budget problem on top of the general fund shortfall; REET revenues go toward maintenance, debt service, and capital projects in several areas including parks and transportation. Seattle should definitely lobby the legislature for more REET authority.

4. Double down on taxing big business

Taxing businesses is an imperfect means of taxing the rich, because there are ways they can pass some of those costs on to the rest of us. But a well-designed tax minimizes that effect, and Seattle’s JumpStart payroll expense tax, focused on large corporations with high-salary employees, likely does a great job.

Excuse me while I take a victory lap. Whenever I think of JumpStart I feel a little thrill of satisfaction — as should everyone involved in the multiyear effort to tax big business, including the ill-fated “head tax” drama of 2017-2018. We knew there were gobs of wealth flowing through this city, we didn’t give up, and eventually we tapped into a vein and out flowed $300 million a year. Just like that.

Probably the easiest way for the City to raise more progressive revenue is to ‘turn up the dial’ on JumpStart. There are a number of ways to do this. My favorite idea doesn’t even involve raising the rates. Instead, simply reset the total payroll and employee compensation thresholds back to what they were when the tax started in 2021, namely $7 million and $150,000, before several years of major inflation adjustments.

If Initiative 137 qualifies for the November ballot, Seattle voters will soon weigh in on another option. The House Our Neighbors campaign hopes to fund Seattle’s new social housing developer with a tax similar to JumpStart but based on employers’ compensation to individual employees in excess of $1 million.

San Francisco and Portland have taken yet another approach to taxing big business. Both cities have implemented taxes specifically on corporations whose CEO or highest-paid executive is paid at least 100 times more than its median worker. San Francisco’s version is a graduated surcharge on existing gross receipts and payroll taxes, and it brought in over $200 million last year. San Francisco’s mayor is now proposing mostly gutting the tax as part of an effort to cozy up to business and revitalize the economy — politics are complicated down there, at least as much as they are here.

5. Grab bag

Last year, I served on the Seattle Revenue Stabilization Workgroup, which was co-created by Mayor Harrell and former Councilmember Teresa Mosequda and tasked with assessing new revenue options in the context of the City’s budget shortfall. The Transit Riders Union, of which I am an elected officer and an employee, published our own report alongside the final report of the workgroup, and in it there are more ideas for taxing the rich. But they don’t have solid city-level precedents in the US, so to abide by my own rules for this series I will only mention a few of them briefly:

Luxury taxes: The idea is simple. Seattle can levy excise taxes on the sale or purchase of specific goods. So think of stuff that rich people buy, and tax that! How about luxury cars and boats? But there’s the rub. Statewide, that might work. But try to do that in a single city, and if people can easily travel a few miles further to purchase the same thing without the tax, they’ll probably do it. Cars are easy to move! In fact, McLaren Seattle is already located in Bellevue.

Can other cities show us how to get around this problem? Atlantic City has something called a luxury tax. But it covers things like rentals of beach chairs and cabanas, so they’re not exactly squeezing the big spenders. My best idea so far is to tax luxury appliances and goods needed for high-end home construction or renovation — like when the First Light penthouse owner decides to upgrade his Miele appliance package. It would be impractical to take possession of such goods outside their eventual destination, so as long as the tax is applied at the point of delivery, this might work. Admittedly it feels like a cash grab. But that’s kind of the name of the game here.

Professional services excise tax: Speaking of taxing things that rich people buy, there’s a major loophole in our sales tax that Seattle could try to close. If you hire a plumber to fix a leaky pipe, you pay sales tax on your bill. But when the First Light penthouse owner hires an architect to redesign the interior or a financial advisor to manage their vast wealth, they won’t pay sales tax, because those services are exempt.

Washington isn’t unusual in this respect; as far as I can tell, only New Mexico, South Dakota, and Hawaii impose sales tax on professional services. Exempting such services doesn’t seem to be backed by any good reasons, only by the substantial lobbying power of professional groups. Seattle could try to remedy this with an excise tax, but it would have to be structured in a way that didn’t too closely mirror sales or business and occupation taxes, which are regulated by state law.

Estate and inheritance taxes: It’s a sad day. The First Light penthouse owner was driving his McLaren way over Seattle’s speed limit and lost control. Luckily no one else was hurt, but he’s no longer with us. When his estate passes on to his heirs, Washington state will take a cut. Tax rates range from 10% to 20%, in graduated tiers based on estate value in excess of about $2 million. Could Seattle add its own city-level estate tax? Maybe. It’s unclear whether special state authorization is needed for this, but it’s worth a try.

The other way to get at dead rich people’s wealth is through an inheritance tax. The tax base would be different: not Seattle estates, but Seattle residents who receive an inheritance from anywhere. Washington used to have an inheritance tax, and at least six states currently have one; in Maryland and Nebraska, county governments collect the revenue, so that’s kind of a local precedent. Trying to implement a Seattle-only inheritance tax would carry legal risks and practical challenges, especially since we have no income tax infrastructure to build upon.

With most of these tax-the-rich ideas, there’s also the possibility that some taxpayers might relocate outside Seattle to avoid paying. It’s a danger that’s often exaggerated by opponents of progressive taxation, but it should be considered when setting tax rates and estimating revenue.

This year, for the first time since I’ve been paying attention, Washington lost the title of the state with the most regressive tax system. That’s thanks to the new state capital gains tax, and to Seattle’s JumpStart tax, which was also included in the analysis by the Institute for Taxation and Economic Policy. Washington is now way down in second place, having passed the crown to Florida. In other words, we still have a long way to go to make our tax system more equitable, and budget shortfall or not, Seattle shouldn’t shy away from taxing the rich.

This is part three in the Policy Lab series. Check out the introduction and second installment on mode shift incentives. And watch for more installments!

Katie Wilson is General Secretary of the Transit Riders Union, a Seattle-based organization advocating for improving transit quality and making access more equitable.